The annals of art history are replete with towering figures whose innovations and masterpieces have irrevocably shaped our understanding of aesthetic expression. Alongside these luminaries, however, exist numerous other artists, competent and dedicated, who contributed to the rich tapestry of their era's visual culture, often working in the stylistic currents established by their more famous contemporaries. Thomas Hand (1771–1804) is one such figure, an English painter of rural landscapes and genre scenes whose career, though brief, offers a glimpse into the artistic preoccupations and market demands of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Britain. His work is inextricably linked with that of the celebrated George Morland, whose style Hand emulated with considerable skill.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in 1771, Thomas Hand entered a world where British art was gaining unprecedented confidence and international recognition. The Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768 under the presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds, had become a focal point for artistic training, exhibition, and discourse. While detailed records of Hand's early life and formal training are scarce, it is probable that he, like many aspiring artists of his generation, would have sought instruction through apprenticeship, by copying masterworks, and by attending the Royal Academy Schools or other drawing academies that proliferated in London.

The artistic environment in London during Hand's formative years was vibrant. Painters like Thomas Gainsborough, who had passed away in 1788 but whose influence lingered, had masterfully depicted both elegant portraiture and idyllic, rustic landscapes. Richard Wilson, another foundational figure, had established a tradition of classical landscape painting infused with a British sensibility. The taste for landscape and genre scenes was growing, fueled by an increasingly prosperous middle class and a romantic appreciation for the countryside, often viewed through the lens of the Picturesque aesthetic.

It was within this milieu that Thomas Hand developed his artistic inclinations. His primary path to developing his skills and finding a niche appears to have been through a close association with George Morland (1763–1804), one of the most popular and prolific painters of the period. The exact nature of their initial connection is not definitively documented, but it is widely accepted that Hand became a pupil, assistant, or at the very least, a dedicated follower and imitator of Morland.

The Overwhelming Influence of George Morland

George Morland was a phenomenon in his time. Known for his rapid painting technique and his charming, often sentimental, depictions of rural life, cottage scenes, animals (especially pigs, horses, and donkeys), coastal views, and scenes of smugglers or gypsies, Morland's work resonated deeply with contemporary tastes. His paintings were widely reproduced as engravings, further popularizing his style and subject matter. Despite his commercial success, Morland's life was notoriously dissolute, marked by debt, heavy drinking, and a constant evasion of creditors, which tragically led to his early death in a sponging-house, coincidentally in the same year as Hand's own demise.

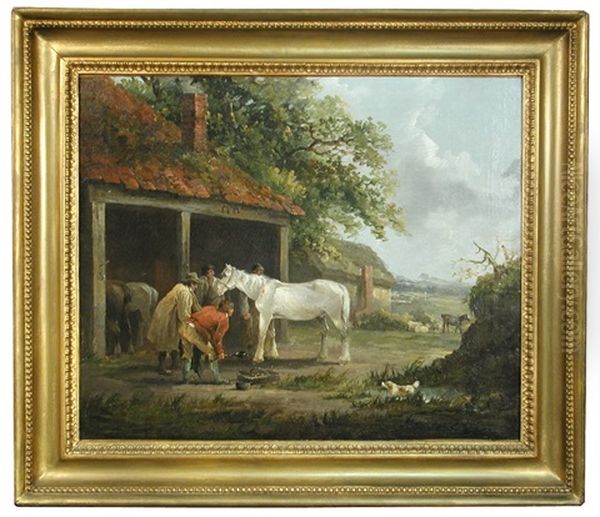

Thomas Hand's artistic output is so closely aligned with Morland's that distinguishing between their works can sometimes be challenging for those not intimately familiar with their respective oeuvres. Hand adopted Morland's characteristic subjects: tranquil farmyards, rustic figures tending to livestock, charmingly dilapidated cottages nestled in verdant landscapes, and intimate portrayals of domestic animals. He also emulated Morland's fluid brushwork, his earthy palette, and his ability to capture the textures of rural life – the rough-hewn wood of a fence, the shaggy coat of a donkey, or the muddy ground of a farm lane.

This close stylistic adherence suggests that Hand may have worked directly in Morland's studio, perhaps assisting with backgrounds, producing copies of Morland's popular compositions for a wider market, or creating variations on Morland's themes. Such arrangements were not uncommon in the period, allowing a successful artist to meet demand and providing a learning opportunity and livelihood for assistants. Hand's works, while often lacking the ultimate spark of genius or the effortless vivacity of Morland's best paintings, are nonetheless competently executed and possess a charm of their own.

Representative Works and Artistic Style

Given his short life and his position as a follower, Thomas Hand did not produce a vast or widely documented body of uniquely identifiable masterpieces. Instead, his "representative works" are best understood as those paintings that exemplify his adherence to the Morlandesque style. These typically include:

Rural Courtyard Scenes: Paintings depicting figures, often children or farmhands, interacting with animals like pigs, donkeys, or horses within the setting of a farmyard or near a cottage. These scenes are characterized by a focus on the picturesque details of rural life.

Landscapes with Figures and Animals: Compositions showing travellers on a country road, shepherds with their flocks, or rustic figures resting beneath trees. The landscapes themselves are usually gentle and bucolic, rendered with soft light and an appreciation for natural textures.

Animal Studies: Hand, like Morland, clearly had an affinity for depicting animals. His portrayals of pigs, often shown snuffling in the dirt or resting contentedly, are particularly characteristic and echo Morland's famous affection for these subjects.

His artistic style can be summarized as picturesque and naturalistic, with a tendency towards the sentimental, a quality highly prized in the popular art of the day. He employed a relatively subdued palette, dominated by earthy browns, greens, and greys, occasionally enlivened by touches of brighter color in the figures' clothing. His brushwork, while aiming for Morland's fluidity, could sometimes be a little tighter or more meticulous, betraying the hand of a careful student rather than an impetuous master.

The compositions are generally well-balanced, often focusing on a central group of figures or animals, with the surrounding landscape providing a harmonious backdrop. There is an intimacy to his scenes, drawing the viewer into a seemingly simpler, more innocent world, far removed from the burgeoning industrialization that was beginning to transform other parts of Britain.

Exhibitions and Contemporary Recognition

Thomas Hand did achieve a measure of recognition during his lifetime, primarily through exhibitions at the Royal Academy in London. He is recorded as having exhibited there on several occasions between 1792 and 1804. For an artist of his standing, exhibiting at the Royal Academy was a significant achievement, offering visibility to potential patrons and critics. The titles of his exhibited works, such as "A Farmyard" or "Landscape with Figures," confirm his dedication to the rustic genre popularized by Morland.

The critical reception of Hand's work, if any was extensively recorded, would likely have acknowledged his skill while noting his dependence on Morland's style. In an era that was beginning to value originality more highly, particularly within the intellectual circles of the art world, being perceived primarily as an imitator, however skilled, would have limited his ascent to the highest ranks of artistic esteem. However, for the broader art-buying public, works in the popular style of Morland, whether by the master himself or by a competent follower like Hand, were highly desirable.

The Context: British Landscape and Genre Painting

To fully appreciate Thomas Hand's contribution, it is essential to place him within the broader currents of British art at the turn of the nineteenth century. The period was a golden age for British landscape and genre painting. Artists were increasingly turning their attention to the native scenery and the lives of ordinary people, moving away from the grand historical and mythological subjects that had dominated academic hierarchies.

The Picturesque movement, championed by theorists like William Gilpin and Uvedale Price, encouraged an appreciation for landscapes that were irregular, varied, and evocative, often incorporating elements like rustic cottages, ancient trees, and winding paths. This aesthetic provided a fertile ground for artists like Morland and Hand. Francis Wheatley (1747–1801), with his popular "Cries of London" series and sentimental rural scenes, also catered to this taste for charming depictions of everyday life.

Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759–1817) was another contemporary who excelled in picturesque landscapes and genre scenes, often featuring Welsh scenery or rustic figures. His work shares some thematic similarities with Hand's, though Ibbetson often displayed a more refined touch and a wider range of subject matter.

Animal painting was also a burgeoning specialism. Sawrey Gilpin (1733–1807), uncle of William Gilpin, was a renowned animal painter, particularly of horses, and his work set a high standard. Morland's own skill in animal depiction was a key part of his appeal, a skill that Hand diligently sought to emulate. The affection for animals, both domestic and wild, was a growing cultural trend, reflected in the art of the period.

While Hand operated within this rustic and picturesque tradition, other landscape painters were pushing boundaries in different directions. John Constable (1776–1837) and J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), Hand's near-contemporaries, were embarking on careers that would revolutionize landscape painting. Constable, with his deep attachment to his native Suffolk scenery and his scientific observation of natural effects, and Turner, with his sublime and increasingly abstract visions of nature's power, represented a more ambitious and innovative approach to landscape art. Hand's work, by contrast, remained firmly rooted in the more modest, anecdotal tradition of Morland.

Other landscape artists of the time included Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812), whose work ranged from dramatic coastal scenes and battles to more tranquil picturesque landscapes. His theatrical flair and technical versatility made him a significant figure. The Norwich School of painters, which began to coalesce around John Crome (1768–1821) and John Sell Cotman (1782–1842) in the early 1800s, also represented an important regional development in landscape art, emphasizing direct observation and a more sober, naturalistic depiction of the local environment.

Dutch Influences and the British School

It is also worth noting the enduring influence of 17th-century Dutch Golden Age painting on British artists of this period, particularly those working in genre and landscape. The works of artists like Adriaen van Ostade, with his lively peasant scenes, Paulus Potter, celebrated for his depictions of cattle in landscapes, and Aelbert Cuyp, known for his luminous pastoral views, were avidly collected in Britain and provided models for British painters. George Morland was certainly aware of this tradition, and his scenes of rustic interiors and farm animals owe a debt to these Dutch precursors. Thomas Hand, by extension, inherited this influence through his association with Morland.

The British school was, in a sense, finding its own voice by assimilating and reinterpreting these continental traditions, adapting them to British scenery and sensibilities. The focus on everyday life, the appreciation of natural beauty, and the touch of sentimentality that characterized much of Morland's and Hand's work can be seen as part of this broader cultural phenomenon.

Hand's Collaborators and Contemporaries: A Wider Circle

While Morland was undoubtedly the central figure in Hand's artistic orbit, the London art world was a relatively close-knit community. Artists often knew each other, visited each other's studios, and frequented the same coffee houses and print shops. It is likely that Hand would have been acquainted with other artists working in similar veins or exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

Painters like William Shayer (1787–1879), though his main period of activity was later, continued the tradition of rustic genre scenes well into the 19th century, demonstrating the enduring appeal of the subjects Hand painted. The lineage of Morland's influence can be traced through numerous minor painters who found a ready market for similar compositions.

The engravers who reproduced Morland's paintings also played a crucial role in disseminating his style. Artists like William Ward (who was Morland's brother-in-law) and John Raphael Smith produced numerous prints after Morland, making his imagery accessible to a wide audience. Hand's own work, by its similarity, benefited from this widespread familiarity with Morland's aesthetic.

Untimely Death and Artistic Legacy

Thomas Hand's career was cut short by his death in London in December 1804, at the age of just 33. This was, remarkably, the same year that George Morland died, also prematurely. Hand's early demise limited his opportunity to develop a more independent artistic voice or to build a more substantial oeuvre. Consequently, he remains a relatively minor figure in the grand narrative of British art.

His legacy is primarily that of a competent and faithful follower of George Morland. His paintings serve as a testament to Morland's immense popularity and the pervasive influence of his style. For art historians and collectors, Hand's work is interesting for several reasons: it helps to illuminate the studio practices of the period, the dynamics of master-pupil relationships, and the market for popular art. His paintings, when they appear at auction or in collections, are often catalogued with clear reference to their Morlandesque qualities.

While not an innovator, Thomas Hand played a role in satisfying the contemporary demand for charming rural scenes. His works capture a particular vision of the English countryside – idealized, perhaps, but rendered with affection and skill. They offer a window into a world that was rapidly changing, and they preserve a sense of the picturesque charm that captivated the imaginations of his contemporaries.

In the broader context of art history, artists like Thomas Hand are important because they represent the bedrock of artistic production. Not every artist can be a Turner or a Constable, but the collective output of diligent painters like Hand contributes to the richness and diversity of a nation's artistic heritage. They demonstrate the pervasiveness of dominant styles and the ways in which artistic influence is transmitted and adapted.

Conclusion: A Modest but Valued Contributor

Thomas Hand's story is a reminder that the art world is an ecosystem, with artists of varying degrees of originality and fame all playing a part. His decision to closely follow the style of George Morland was a pragmatic one, allowing him to tap into a proven market and to hone his skills under the shadow of a popular master. While his own artistic personality may have been subsumed by this powerful influence, his paintings remain as pleasing examples of late 18th and early 19th-century British rustic genre.

He worked alongside and was contemporary with a host of other talented individuals, from the towering figures of Turner and Constable, who were just beginning their revolutionary careers, to established names like de Loutherbourg and Francis Wheatley, and specialists like Sawrey Gilpin. His connection to Morland places him firmly within a tradition that looked back to Dutch masters like Ostade and Potter, while also reflecting the burgeoning British fascination with its own landscape and rural life.

Though his life was short and his fame modest, Thomas Hand left behind a body of work that continues to find appreciation for its quiet charm and its skillful execution. He remains a figure of interest for those studying the circle of George Morland and the broader phenomenon of popular art in Georgian England, a diligent craftsman who captured the idyllic, picturesque spirit of his age. His paintings offer a gentle, unassuming counterpoint to the grander artistic statements of his time, reminding us of the enduring appeal of simple, well-told stories of rural life.