Introduction: A Victorian Favourite

George Armfield, born George Armfield Smith in 1808, stands as one of the most prolific and popular animal painters of nineteenth-century Britain. Working during a period of immense national pride and burgeoning middle-class prosperity, Armfield tapped into the Victorian era's deep affection for domestic animals, particularly dogs. His canvases, filled with lively terriers, noble hounds, and affectionate spaniels, captured the hearts of the public and secured his place as a leading figure in the genre of animal and sporting art. Though his life was marked by both considerable success and personal hardship, his artistic legacy endures, celebrated for its vibrant realism and empathetic portrayal of the animal world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

George Armfield Smith entered the world in Bristol, England, in 1808. His father, William Armfield Hobday (1771-1831), was himself a respected portrait painter who maintained a studio in Pall Mall, London. This artistic environment undoubtedly influenced young George, although his path towards painting was not initially straightforward. His father, perhaps wary of the precariousness of an artist's life, initially intended for George to be apprenticed to a fishing tackle maker.

However, George's innate talent for drawing and painting could not be suppressed. He demonstrated a remarkable aptitude for capturing the form and spirit of animals from a young age. Recognizing his son's true calling, his father eventually relented and provided him with an artistic education. This early training, combined with his natural observational skills, laid the foundation for his future career.

His precocious talent was evident early on. At the remarkably young age of sixteen, George saw his work accepted for exhibition at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London. The painting, titled "Lion," depicted a Newfoundland dog, showcasing his early focus on canine subjects. This debut marked the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship with the major art institutions of his day.

Forging an Identity: From Smith to Armfield

In the 1830s, George began exhibiting his works more regularly, initially under his given surname, Smith. He quickly gained recognition for his skill in depicting animals, particularly dogs engaged in various activities, from resting by the hearth to participating in the hunt. His paintings resonated with a public increasingly interested in both pets and country sports.

A significant change occurred around 1840 when he decided to exhibit under the name George Armfield. The reasons for this change are not definitively documented, but it may have been an attempt to distinguish himself further in the crowded London art scene, perhaps leveraging the "Armfield" part of his father's name (William Armfield Hobday) while dropping the more common "Smith." Whatever the motivation, "George Armfield" became the name under which he achieved widespread fame.

Under his new professional identity, Armfield's career flourished. He became a regular contributor to the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy and the British Institution, and later at the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) on Suffolk Street. His consistent presence at these key venues ensured his work was seen by critics, collectors, and the general public, solidifying his reputation.

The Canine Specialist: Subject Matter and Popularity

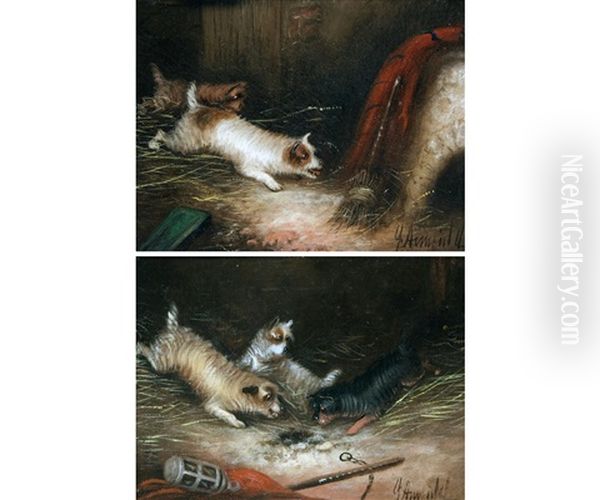

While Armfield painted various animals, including horses, foxes, deer, and occasionally more exotic creatures drawn from his personal menagerie, he became overwhelmingly famous for his depictions of dogs. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the distinct character and anatomy of numerous breeds, particularly terriers (like Skye Terriers and Fox Terriers), spaniels (such as King Charles Spaniels), and various types of hounds used in hunting.

His paintings often depicted dogs in action: terriers eagerly "ratting" in a barn, hounds flushing out game, or spaniels patiently waiting for their masters. These scenes appealed to the Victorian interest in narrative and activity. He was particularly adept at portraying the textures of fur, the dampness of a dog's nose, and the intelligent, alert expressions in their eyes. Works like "Terriers Ratting," "Gundogs and Hounds," and numerous untitled studies of spaniels and terriers became his trademark.

The popularity of Armfield's work was immense. Britain in the 19th century saw a surge in pet ownership and the formalization of dog breeds through kennel clubs and shows. Landed gentry and the rising middle class alike commissioned portraits of their beloved animals or purchased scenes depicting popular sporting pursuits. Armfield's ability to render dogs with both accuracy and charm perfectly met this demand. His paintings were not just animal portraits; they were lively vignettes of canine life that viewers found relatable and engaging.

Artistic Style and Technique

George Armfield developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its realism, vibrant brushwork, and strong sense of three-dimensionality. He worked primarily in oils on canvas, employing a technique that balanced detailed observation with painterly energy. His brushstrokes were often broad and confident, particularly when rendering fur, foliage, or earthy foregrounds, giving his work a lively, textured surface.

He had a keen eye for anatomical accuracy, capturing the musculature and skeletal structure beneath the fur, which lent his animals a convincing sense of weight and presence. Unlike the sometimes overly sentimentalized or anthropomorphized animals of his famous contemporary, Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), Armfield generally focused on portraying dogs in naturalistic settings, behaving as dogs do. His realism was a key factor in his appeal.

Armfield masterfully used light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model form and create depth, making his subjects appear almost tangible. His colour palette often favoured rich, earthy tones – browns, ochres, greens, and greys – appropriate for depicting animals in outdoor or rustic indoor settings. This naturalism extended to the environments he painted, whether it was the rough texture of a stable wall, the damp earth of a forest floor, or the cluttered interior of a barn.

His compositions were typically well-balanced, often focusing attention squarely on the animal subjects. He frequently incorporated narrative elements, inviting the viewer to imagine the story behind the scene – the anticipation before the hunt, the satisfaction after a successful ratting expedition, or the quiet companionship between dogs. This combination of technical skill and engaging subject matter made his work highly sought after.

A Life Beyond the Easel: Passions and Personality

George Armfield's life outside his studio was as colourful and dynamic as his paintings. He was known to be a passionate enthusiast of country sports, including horse racing, hunting with hounds, and coursing (hunting game, usually hares, with greyhounds). These interests provided him with firsthand knowledge of the animals he depicted and the environments they inhabited, lending authenticity to his sporting scenes.

His love for animals extended beyond his artistic subjects. He reportedly kept a diverse collection of animals at his home – a sort of "mini-menagerie" – which included not only dogs and horses but also foxes and even seals. These animals served as readily available models, allowing him to study their forms and behaviours closely. This deep familiarity is evident in the lifelike quality of his work.

Armfield married three times. Little is known about his first wife. His second wife, Sarah Yeulett, bore him a daughter. His third wife, whose name is less consistently recorded but often cited as Sarah (possibly Sarah Daniels), gave birth to twelve children. Managing such a large family must have presented significant challenges, both personal and financial. Some of his children reportedly followed artistic or related pursuits, continuing the family tradition established by their grandfather, William Armfield Hobday.

Contemporary accounts suggest Armfield lived life with gusto. His enthusiasm for sports sometimes spilled over into heavy gambling, particularly on horse races. He was known for his extravagance and, at times, lived beyond his means, despite earning a considerable income from his popular paintings. This penchant for risk and high living contributed to financial instability later in his life.

Contemporaries and the Victorian Art World

George Armfield operated within a vibrant and competitive art world in Victorian London. Animal painting was a highly respected and commercially successful genre, building on traditions established by earlier artists like George Stubbs (1724-1806) and Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807). Armfield's direct contemporaries included several other notable animal and sporting painters.

Sir Edwin Landseer was undoubtedly the most famous animal painter of the era, favoured by Queen Victoria and known for his dramatic, often anthropomorphic depictions. While Armfield's work was perhaps less grand in ambition, it possessed a directness and naturalism that held wide appeal. Other significant figures in the field included John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865), renowned for his coaching scenes and racehorse portraits, and Richard Ansdell (1815-1885), who often collaborated with landscape painters and depicted dramatic scenes of animals in the Scottish Highlands.

Abraham Cooper (1787-1868) was another prominent painter of horses and battle scenes, while Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902) became famous for his pastoral landscapes featuring cattle and sheep, exhibiting at the Royal Academy for an astonishingly long period. Later in Armfield's career, artists like Briton Rivière (1840-1920) continued the tradition of animal painting, often with a strong narrative or symbolic element. Frederick William Keyl (1823-1871), a German-born artist who worked for Queen Victoria, also specialized in animal subjects. Henry Thomas Alken (1785-1851) and his family were prolific producers of hunting, coaching, and racing prints and paintings. James Ward (1769-1859), though slightly earlier, was also a major figure in animal and landscape painting, known for his powerful depictions.

Armfield exhibited alongside many of the era's most famous artists at the Royal Academy, including narrative painters like William Powell Frith (1819-1909), the Pre-Raphaelites such as Sir John Everett Millais (1829-1896), and later, the classical figures like Lord Frederic Leighton (1830-1896). While his subject matter was specialized, his consistent presence in major exhibitions placed him firmly within the mainstream of Victorian art.

Later Years: Challenges and Declining Health

Despite his considerable success and prolific output, George Armfield's later years were marked by significant challenges. By the 1870s, his eyesight began to fail, a devastating blow for a visual artist reliant on keen observation. He underwent eye surgery around 1872 in an attempt to correct the problem, but it appears to have been unsuccessful, and his vision continued to decline.

This loss of sight inevitably impacted his ability to paint with the same precision and detail that had characterized his earlier work. While he continued to produce paintings, works from his later period are generally considered to be of lesser quality than those from his prime. This decline, coupled with his earlier extravagance and the financial burden of a large family, led to increasing poverty.

The combination of failing health, diminished artistic capacity, and financial distress took a heavy toll. In a moment of despair, Armfield reportedly attempted suicide, a tragic reflection of the hardships he faced. Towards the very end of his life, his plight was recognized by the art establishment that had once celebrated his work. In 1893, the year of his death, the Royal Academy awarded him a charitable pension of £20 to help support him.

George Armfield passed away in Clapham, then a suburb of London, in 1893, at the age of 85. His death marked the end of a long and eventful life dedicated to the art of animal painting.

Enduring Legacy and Collections

George Armfield left behind a substantial body of work and an enduring legacy as one of Britain's foremost painters of dogs and sporting life in the 19th century. His paintings captured a specific aspect of Victorian culture – the nation's love affair with dogs and country pursuits – with unparalleled vibrancy and realism. His ability to convey the individual character and spirit of his canine subjects remains a hallmark of his art.

His influence can be seen in the continuing tradition of animal painting in Britain. While artistic styles evolved, the demand for skilled depictions of animals persisted, and Armfield set a high standard for naturalism and empathetic portrayal within the genre. His work demonstrated that animal painting could be both commercially successful and artistically accomplished.

Today, George Armfield's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections across the United Kingdom and internationally. Notable institutions housing his work include the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum, the Preston Park Museum & Grounds (formerly Preston Hall Museum, Stockton-on-Tees), the Bury Art Museum, Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

His works continue to be popular at auction, attesting to their lasting appeal to collectors of sporting art and canine portraiture. George Armfield's contribution to British art lies in his dedicated and skillful chronicling of the animal world, particularly the dogs that shared the lives of the Victorian people. His canvases remain a testament to his keen eye, his technical proficiency, and his evident affection for his subjects, securing his place in the annals of art history.