The name Cromek resonates in British art history, primarily through two distinct yet related figures: Robert Hartley Cromek (1770-1812), an engraver, editor, and sometimes controversial entrepreneur in the world of William Blake, and his son, Thomas Hartley Cromek (1809-1873), a gifted watercolourist celebrated for his meticulous and evocative depictions of classical and medieval European landscapes and architecture. While the initial query blends aspects of both, this exploration will primarily focus on Thomas Hartley Cromek, the painter, while duly acknowledging the significant, albeit different, artistic contributions and context provided by his father.

The Father's Shadow: Robert Hartley Cromek and the Romantic Era

Before delving into the primary subject, Thomas Hartley Cromek, it is essential to address his father, Robert Hartley Cromek, whose life and career significantly shaped the artistic environment his son would later enter. Born in 1770 in Kingston upon Hull, Robert Hartley Cromek initially pursued a legal career but soon gravitated towards literature and the arts. He established himself in London as an engraver and publisher, demonstrating a keen entrepreneurial spirit, though his business practices often drew criticism, most notably from the visionary artist and poet William Blake.

Robert Cromek's most famous, or infamous, association is indeed with William Blake. He commissioned Blake to produce a series of twenty drawings illustrating Robert Blair's poem "The Grave." Blake expected to engrave these himself, a common practice for artists wishing to maintain control over the final printed image. However, Cromek, perhaps citing Blake's unconventional engraving style as commercially unviable, controversially assigned the engraving task to Luigi Schiavonetti. Schiavonetti, an Italian engraver who had studied under the renowned Francesco Bartolozzi, produced plates that were more aligned with the popular, softer, and more conventional tastes of the time. The resulting 1808 edition of "The Grave," with Schiavonetti's engravings after Blake's designs, was a commercial success, but it became a significant point of contention and bitterness for Blake, who felt betrayed and financially exploited.

Another contentious project involved Geoffrey Chaucer's "Canterbury Pilgrims." Blake had been working on his own painted and engraved version of the "Procession of Chaucer's Pilgrims to Canterbury." According to Blake and his supporters, Robert Cromek saw Blake's initial concept and then commissioned a similar subject from the popular painter Thomas Stothard, a friend of Blake who was perhaps unaware of the full context. Stothard’s more conventional and academically pleasing rendition was then engraved, again by Schiavonetti initially, and after Schiavonetti's death, completed by others including Nicola Schiavonetti (Luigi's brother) and James Heath. This venture further fueled Blake's resentment, viewing Cromek as a figure who profited from the ideas of others and prioritized commercial appeal over artistic integrity. Blake famously caricatured Cromek and his associates in his satirical writings and art.

Despite these controversies, Robert Cromek was a figure of some note in the publishing world. He also published "Reliques of Robert Burns" (1808), collecting previously unpublished poems and letters by the Scottish bard, and "Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song" (1810). His activities, while sometimes ethically questionable by modern standards and certainly by Blake's, highlight the complex interplay between art, patronage, and commerce in the late Georgian and early Romantic periods. He operated within a circle that included not only Blake and Stothard but also other artists like Henry Fuseli, a prominent figure in Romantic art known for his dramatic and often unsettling subjects. Robert Hartley Cromek passed away in 1812, leaving a mixed legacy but undeniably playing a role in the dissemination of important literary and artistic works.

Thomas Hartley Cromek: A Victorian Painter's Pilgrimage

Born on August 8, 1809, in London, Thomas Hartley Cromek, son of Robert, emerged as an artist in a different era, the burgeoning Victorian age, though his artistic sensibilities were deeply rooted in the Romantic appreciation for the past. He did not follow his father into the world of engraving and publishing but instead dedicated himself to the art of watercolour painting, specializing in landscapes and architectural subjects.

His early training is somewhat unclear, but he likely benefited from the artistic environment his father, despite his early death, had been part of. Thomas developed a highly refined technique, characterized by meticulous detail, accurate rendering of architectural forms, and a subtle understanding of light and atmosphere. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1830, marking the beginning of a consistent, though perhaps not spectacularly famous, career.

Travels and Inspirations: Italy and Greece

The defining aspect of Thomas Hartley Cromek's career was his extensive travel, particularly to Italy and Greece, which provided the primary subjects for his art. Like many artists of his generation, including contemporaries such as David Roberts, Samuel Prout, and William Leighton Leitch, Cromek was drawn to the historical and picturesque allure of the Mediterranean. These regions, rich in classical and medieval remains, offered a wealth of inspiration for artists catering to a British public fascinated by the Grand Tour and the historical narratives these sites embodied.

Cromek spent a significant period in Italy, from the early 1830s to the late 1840s, residing for extended periods in Rome and Florence. His Italian views are among his most accomplished works. He meticulously documented ancient Roman ruins, medieval churches, and Renaissance palaces, often imbuing them with a quiet, contemplative dignity. His work shares affinities with that of Samuel Prout, particularly in the detailed rendering of textured stone and the picturesque arrangement of architectural elements, though Cromek’s style often exhibits a slightly more classical restraint compared to Prout’s sometimes more overtly Romantic crumbling textures.

One of his notable works from this period is the "Interior of the Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi," dated 1839. This watercolour showcases his ability to capture the grandeur of Gothic architecture and the play of light within a vast interior space. Such works would have appealed to Victorian audiences interested in both architectural history and the spiritual resonance of such sites. Other Italian subjects included views of the Roman Forum, the Colosseum, and various temples and arches. For instance, a work depicting "The Arch of Titus and the Colosseum, Rome" would have been a classic subject, allowing him to demonstrate his skill in rendering iconic ancient structures. The Arch of Titus itself, a triumphal arch dating from c. 81 AD, was a perennial favorite for artists. Similarly, "The Theatre of Marcellus, Rome," an ancient open-air theatre, would have offered a complex interplay of ruined grandeur and picturesque decay that was highly valued.

Cromek also journeyed to Greece, a destination that, while part of the classical world, was perhaps less frequently visited by British artists at the time compared to Italy. His Greek scenes, depicting sites like the Acropolis in Athens, are equally detailed and evocative. These works contributed to the visual understanding of classical Greek architecture and landscape for the British public. His painting "The Acropolis of Athens from the East" (1840s) is a fine example, showing the Parthenon and other structures with careful attention to detail and atmospheric perspective.

Artistic Style and Contemporaries

Thomas Hartley Cromek's style can be situated within the British topographical watercolour tradition, which had evolved from precise, almost cartographic renderings in the 18th century (e.g., Paul Sandby) to more atmospheric and picturesque interpretations in the early 19th century, heavily influenced by artists like J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin. While Cromek's work doesn't possess the revolutionary dynamism of Turner, it exhibits a strong sense of place, a mastery of perspective, and a delicate application of colour.

His contemporaries in the field of architectural and landscape watercolour were numerous. Beyond Samuel Prout and David Roberts (known for his grand views of Egypt, the Near East, and Spain, as well as British subjects), one might consider:

William Leighton Leitch: A Scottish watercolourist, also known for his Italian scenes and as Queen Victoria's drawing master.

James Duffield Harding: A prolific watercolourist and lithographer, influential through his drawing manuals.

Clarkson Stanfield: Renowned for his marine paintings and dramatic landscapes, often with historical or architectural elements.

John Frederick Lewis: Famous for his highly detailed Orientalist scenes, though his meticulous technique shares some common ground with Cromek's precision.

Edward Lear: Known for his nonsense verse but also a highly accomplished topographical artist, whose Italian and Greek views often possess a unique clarity and compositional strength.

William Henry Bartlett: An artist who produced numerous illustrations for travel books, depicting scenes from around the world, including the Mediterranean.

Thomas Allom: An architect and illustrator, whose topographical views, often engraved, were widely disseminated.

Penry Williams: A Welsh artist who spent much of his career in Rome, painting Italian landscapes and genre scenes, a direct contemporary working in similar locations.

Cromek's work was regularly exhibited at prominent London venues, including the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists, from the 1830s through the 1860s. This indicates a consistent professional presence and a degree of recognition within the Victorian art world. His patrons were likely drawn from the educated middle and upper classes who had undertaken their own Grand Tours or who appreciated the cultural and historical significance of the sites he depicted.

The art critic John Ruskin, a dominant voice in Victorian art, championed detailed observation and truth to nature. While Ruskin's highest praise was often reserved for Turner or the Pre-Raphaelites, Cromek's careful delineation of architectural detail and his faithful representation of specific locations would have aligned with some aspects of Ruskinian aesthetics, particularly the emphasis on capturing the character and historical verity of a place.

Specific Works and Their Significance

While a comprehensive catalogue of Thomas Hartley Cromek's oeuvre is not readily available in all sources, certain titles recur and help to define his artistic focus:

"Interior of the Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi" (1839): As mentioned, this work is significant for its depiction of a major medieval monument, showcasing his skill in handling complex interior perspectives and light. Assisi was a key site for those interested in medieval Italian art and spirituality.

"The Arch of Titus and the Colosseum, Rome": This subject combines two of Rome's most iconic ancient landmarks. Such a composition would allow for a powerful juxtaposition of triumphal architecture and the enduring symbol of Roman spectacle.

"The Theatre of Marcellus, Rome": Another important Roman ruin, its semi-circular form and layered history (with later structures built into its fabric) made it a compelling subject for artists interested in the passage of time and the picturesque.

"The Acropolis of Athens from the East" / "The Parthenon, Athens": These works represent his engagement with the heart of classical Greek civilization, capturing the stark beauty and historical weight of these ancient temples.

"The Pope's Palace and Cathedral, Avignon" (exhibited 1836): This indicates his travels extended beyond Italy and Greece to other historically significant European locations, such as the former papal seat in France.

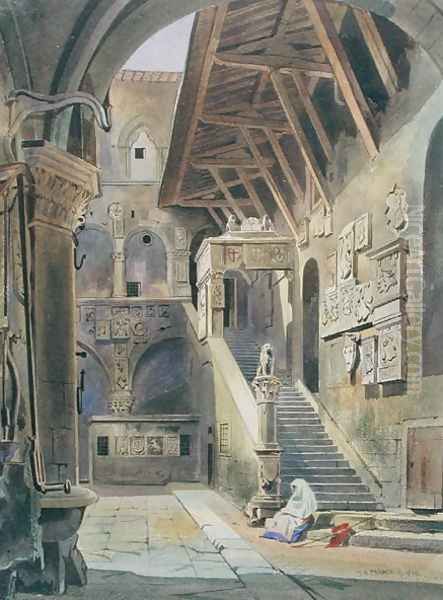

"Court of the Bargello, Florence" (exhibited 1839): Demonstrates his interest in Renaissance architecture and the civic history of Italian city-states.

These works, and others like them, served not only as aesthetically pleasing objects but also as visual records of important historical sites, contributing to the 19th-century British understanding and appreciation of European cultural heritage. They reflect a Victorian fascination with history, archaeology, and the picturesque, filtered through a Romantic sensibility that valued the evocative power of ruins and ancient landscapes.

Later Life and Legacy

Thomas Hartley Cromek continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He resided for many years in Wakefield, Yorkshire, after his return from his extended stays abroad. He died on April 16, 1873, in Wakefield.

His legacy is that of a highly skilled and dedicated watercolourist who specialized in a genre that was immensely popular during the Victorian era. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, his work is valued for its precision, its historical accuracy, and its quiet, evocative beauty. His paintings provide a valuable window into the 19th-century British engagement with the classical and medieval past of Europe.

In distinguishing Thomas Hartley Cromek from his father, Robert, we see two different facets of the British art world. Robert was an entrepreneur of the Romantic era, navigating the complex and often fraught relationships between artists, engravers, and the market, leaving a controversial but impactful mark, especially through his association with William Blake. Thomas, his son, was a practitioner, a dedicated artist who used his considerable talents to capture the enduring allure of historical sites, contributing to the rich tradition of British watercolour painting in the Victorian age. His works remain in various public and private collections, testament to his skill and the enduring appeal of the subjects he chose to depict. He stands as a fine representative of the many talented artists who documented the world for an eager public before the age of widespread photography, his brushstrokes preserving a vision of antiquity that continues to resonate.