Giovanni Battista Busiri (1698-1757) stands as a significant figure in the annals of eighteenth-century Italian art, celebrated particularly for his evocative landscape and architectural paintings, or vedute, that captured the timeless allure of Rome and its surrounding Campagna. An Italian national, born and active in Rome, Busiri's artistic output resonated deeply with the burgeoning number of British and other European travellers undertaking the Grand Tour. His works, often executed in oil, tempera, or delicate watercolour and gouache, served not only as picturesque records of their journeys but also as enduring testaments to the enduring fascination with classical antiquity and the Italian landscape. He was affectionately known by the nicknames Titta or Tittarella, adding a personal touch to his professional identity.

Early Life and Artistic Emergence in Rome

While specific details regarding Giovanni Battista Busiri's formal artistic training and tutelage remain somewhat elusive in historical records, his emergence as a painter in Rome during the early eighteenth century places him squarely within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu. Rome, at this time, was the undisputed cultural capital of Europe, a magnet for artists from across the continent eager to study its classical ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and the works of Baroque masters. It is highly probable that Busiri absorbed the prevailing artistic currents through informal study, observation of established masters, and perhaps association with local workshops or academies, even if a direct master-pupil lineage is not clearly documented.

The artistic environment of Rome would have been rich with influences. Painters like Gaspar van Wittel (Gaspare Vanvitelli), a Dutchman who Italianized his name and became a foundational figure in veduta painting, had already established a strong tradition of detailed cityscape views. Busiri would have been aware of such precursors, whose meticulous approach to topography laid the groundwork for the next generation of view painters. The general atmosphere was one of reverence for the classical past, coupled with a growing appreciation for the picturesque qualities of the natural landscape, often animated by contemporary life.

The Roman Landscape and Architectural Visions

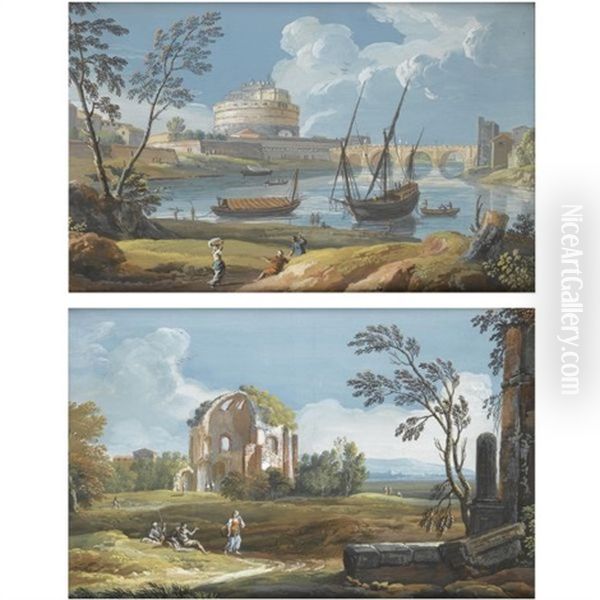

Busiri's primary subject matter was the city of Rome and its environs. He possessed a keen eye for the architectural grandeur of ancient monuments, the serene beauty of the Roman Campagna, and the lively atmosphere of contemporary urban spaces. His paintings often depict iconic landmarks such as the Colosseum, the Roman Forum, the Pantheon, and various triumphal arches and temples. These were not mere topographical renderings; Busiri imbued his scenes with a sense of atmosphere, often employing a delicate palette and a sensitivity to light that captured the unique golden glow of the Roman sky.

His architectural views, such as the renowned Veduta del Colosseo con figure (View of the Colosseum with figures), showcase his skill in perspective and his ability to render complex structures with accuracy while also populating them with small figures that add scale and a sense of daily life. These figures, often depicted as travellers, locals, or shepherds, animate the scenes and connect the ancient past with the present of Busiri's time. Similarly, his Veduta di Piazza Navona (View of Piazza Navona) captures the dynamic public life of one of Rome's most famous squares, framed by its magnificent fountains and Baroque architecture.

Beyond the city walls, Busiri was equally adept at portraying the pastoral landscapes of the Campagna. Works like Veduta di Ponte Milvio (View of the Milvian Bridge) illustrate his appreciation for the rustic charm of the Roman countryside, with its rolling hills, ancient aqueducts, and meandering rivers. These scenes often evoke a sense of Arcadian tranquility, appealing to the romantic sensibilities of his patrons.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Giovanni Battista Busiri's artistic style is characterized by a distinctive blend of precision and freedom. While his architectural renderings demonstrate a careful attention to detail and perspective, his brushwork, particularly in his tempera and watercolour pieces, could be quick and fluid. This approach allowed him to capture the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere effectively. His use of colour was often vibrant yet harmonious, contributing to the overall pleasing and picturesque quality of his compositions.

He frequently worked in tempera on paper or panel, a medium that allowed for fine detail and a smooth finish. His watercolours and gouaches, often smaller in scale, were particularly popular with Grand Tourists due to their portability and intimate charm. These works often feature a delicate application of washes, with details picked out in pen and ink, typically brown ink, lending warmth and definition to the forms. Rich shadows are a common feature, adding depth and drama to his scenes, whether they depict sun-drenched ruins or shaded pastoral groves.

Busiri's compositions are generally well-balanced, guiding the viewer's eye through the scene with a clear sense of spatial recession. He often employed traditional landscape conventions, such as framing elements in the foreground (trees, architectural fragments) to enhance the sense of depth and draw attention to the main subject in the middle or background.

The Grand Tour and Busiri's Clientele

The eighteenth century witnessed the peak of the Grand Tour, an educational rite of passage for young European noblemen and wealthy commoners, particularly from Britain. Italy, with Rome as its ultimate destination, was central to this tradition. Grand Tourists sought to immerse themselves in classical culture, art, and history. Consequently, there was a high demand for visual mementos of their travels, and artists like Busiri catered directly to this market.

Busiri's paintings, especially his smaller, more easily transportable works, became highly sought-after "souvenirs d'Italie." They offered an idealized yet recognizable vision of Rome and its surroundings, perfectly aligning with the romantic and classical aspirations of the Grand Tourists. His ability to produce charming and accurate views at a relatively accessible price point compared to some of the more established masters likely contributed to his popularity. Patrons would often commission sets of views depicting their favourite sites, which they would then take back to their home countries, helping to disseminate images of Italy and its artistic heritage across Europe. The Windham family of Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, for instance, were significant patrons, and their collection provides valuable insight into the types of works favoured by British travellers.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Rome

Giovanni Battista Busiri operated within a thriving community of artists in Rome, many of whom were also engaged in landscape and veduta painting. Understanding his work in relation to his contemporaries helps to contextualize his contributions.

One of the most prominent figures in Roman veduta painting during Busiri's lifetime was Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765). Panini was renowned for his grand, often imaginary, views of Roman ruins (capricci) and his depictions of contemporary Roman festivals and ceremonies. While Busiri's work was generally more modest in scale and focused on actual views, he would undoubtedly have been aware of Panini's dominant presence.

Andrea Locatelli (1695-1741) was another significant contemporary landscape painter in Rome. Locatelli specialized in idealized classical landscapes, often with mythological or biblical figures, but also painted topographical views. There is evidence suggesting that Busiri's style was influenced by Locatelli, particularly in the handling of foliage and atmospheric effects. Some sources even suggest a period of study or close association.

Paolo Anesi (1697-1773) was also active in Rome, known for his landscapes and vedute that often featured a softer, more atmospheric quality. He, along with Locatelli and Busiri, contributed to the development of Roman landscape painting in the first half of the eighteenth century.

The French artist Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789) spent a significant period in Rome (from 1734 to 1753), overlapping with Busiri's active years. Vernet became famous for his dramatic seascapes and landscapes, and there are records indicating contact between Vernet and Busiri. They shared an interest in capturing natural effects and catering to an international clientele.

While primarily known for his etchings, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) was a towering figure whose powerful and dramatic views of Roman antiquities (Vedute di Roma) profoundly shaped the European imagination of Rome. Though working in a different medium, Piranesi's vision of a majestic and often sublime Rome was part of the same cultural fascination that Busiri tapped into.

Other landscape artists active in Italy during this period, whose work formed part of the broader artistic context, include the Venetian Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768), who, though primarily associated with Venice, also painted Roman views during his visits. His meticulous detail and luminous cityscapes set a high standard for veduta painting. Canaletto's nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (1721-1780), also followed in this tradition, working in Rome among other European cities.

The pastoral landscapes of Francesco Zuccarelli (1702-1788), often featuring idyllic scenes with peasants and livestock, were popular throughout Europe and represent another facet of eighteenth-century landscape painting. Similarly, Marco Ricci (1676-1730), active in the earlier part of Busiri's career, was known for his romantic landscapes, ruin paintings, and collaborations with other artists.

The Welsh painter Richard Wilson (1714-1782), often called the "father of British landscape painting," spent several years in Italy (1750-1757), including Rome, where he transitioned from portraiture to landscape. He is known to have associated with artists like Vernet and would have been part of the same circle of foreign artists and patrons that Busiri encountered. Wilson's classically inspired landscapes show the profound impact of the Italian sojourn.

Later in the century, artists like Jakob Philipp Hackert (1737-1807), a German landscape painter who worked extensively in Italy, continued the tradition of detailed and picturesque views, often for royal patrons. The French painter Hubert Robert (1733-1808), known as "Robert des Ruines," also spent considerable time in Rome, creating imaginative compositions of ruins that blended observation with fantasy.

This vibrant network of native Italian and foreign artists created a dynamic environment where styles and ideas were exchanged, and the demand for Italian views, particularly of Rome, was consistently high. Busiri carved out a successful niche within this competitive landscape.

Influence, Legacy, and Collections

Giovanni Battista Busiri's influence can be seen in the continued popularity of Roman views among both artists and collectors. His works helped to solidify a particular vision of Rome – one that was both historically resonant and picturesquely appealing. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as Panini or Canaletto, his contribution to the veduta genre, particularly for the Grand Tour market, was significant.

His paintings were collected by discerning patrons and found their way into numerous private collections in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. Today, works by Giovanni Battista Busiri are held in several important public collections. The British Museum in London and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge house significant holdings of his drawings and paintings, showcasing the range of his work, including views of Rome, Tivoli, and other sites in the Campagna. The "Phillips Museum in Rome" is also cited in some sources as holding his works, though this institution is less widely known in the context of major Busiri collections compared to the British institutions. His art continues to appear at auctions, attesting to its enduring appeal and historical value.

The academic world recognizes Busiri as a skilled and prolific painter who played an important role in satisfying the eighteenth-century appetite for Italian scenery. His works are valuable historical documents, offering insights into the appearance of Rome and its surroundings in his time, as well as reflecting the cultural tastes and aspirations of the era. Scholars appreciate his ability to combine topographical accuracy with artistic sensibility, creating views that are both informative and aesthetically pleasing. His art reflects the broader European fascination with classical antiquity and the "Eternal City," a fascination that was a cornerstone of Enlightenment culture.

Conclusion: The Enduring Charm of Busiri's Rome

Giovanni Battista Busiri, through his dedicated portrayal of Rome and its environs, created a body of work that continues to charm and inform. As an Italian artist catering to an international audience, he skillfully navigated the demands of the market while maintaining a distinct artistic voice. His vedute, whether grand depictions of ancient monuments or intimate sketches of the Campagna, offer a window into the eighteenth-century experience of Rome, capturing the light, atmosphere, and enduring spirit of a city that has captivated artists and travellers for centuries. His legacy lies in these picturesque visions, which not only served as cherished souvenirs for Grand Tourists but also contributed to the rich tapestry of European landscape painting, ensuring that the beauty of Rome, as seen through his eyes, would be preserved for posterity. His contribution, though perhaps quieter than some of his more bombastic contemporaries, remains a vital part of Rome's artistic heritage.