Thomas Ivester Lloyd stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tradition of British sporting and animal art. Active during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period of great social and artistic change, Lloyd carved a niche for himself with his evocative and anatomically precise depictions of horses, hounds, and the vibrant world of equestrian pursuits. His work not only captures the thrill of the hunt and the elegance of equine sports but also serves as a valuable historical record of a way of life that was integral to British identity. Unlike the revolutionary modernists like Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse who were his contemporaries and were deconstructing form, Lloyd remained dedicated to a more traditional, representational style, finding his artistic truth in the faithful portrayal of the natural world and its dynamic inhabitants.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in 1873 in Liverpool, England, Thomas Ivester Lloyd's early life and specific formative influences are not as extensively documented as some of his more famous artistic peers. However, it is evident from his later specialization that he developed a profound connection with animals, particularly horses and dogs, from a young age. The English countryside, with its ingrained traditions of hunting, racing, and rural life, would have provided ample inspiration. This era, the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, still held equestrian activities in high esteem, not just as sport but as an essential part of social and agricultural life. It's likely that Lloyd's early experiences involved direct observation of these animals, fostering an understanding of their movement, anatomy, and character that would become hallmarks of his art.

His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training, a crucial step for any aspiring artist of his time. Lloyd enrolled at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London, one of the most important art institutions in Britain. The Slade, under influential figures like Henry Tonks, Philip Wilson Steer, and Frederick Brown, was known for its emphasis on draughtsmanship and direct observation, principles that clearly resonated with Lloyd's artistic temperament. While some of his Slade contemporaries, such as Augustus John or William Orpen, would go on to explore portraiture and more avant-garde styles, Lloyd's passion remained firmly rooted in the animal kingdom and the sporting life that surrounded it.

The Call of Duty: Military Service

The trajectory of Lloyd's life, like that of many young men of his generation, was interrupted by conflict. He served in the British Army during two major wars: the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and later, World War I (1914-1918). During the Great War, he held the rank of Captain in the Royal Field Artillery. Military service, particularly in cavalry and artillery units, would have brought him into even closer contact with horses, albeit in the grim context of warfare. This experience, while undoubtedly challenging, likely deepened his appreciation for the strength, resilience, and character of these animals.

While not primarily known as a war artist in the vein of Paul Nash or C.R.W. Nevinson, who documented the stark realities of the Western Front with a modernist sensibility, Lloyd's military experiences may have subtly informed his work. The discipline of military life and the keen observational skills required in the field could have further honed his artistic eye. Moreover, the horse was still a vital component of military operations during this period, and his firsthand experience would have provided him with an unparalleled understanding of equine anatomy and movement under various conditions.

A Dedication to Sporting Art

Upon returning to civilian life and his artistic pursuits, Thomas Ivester Lloyd fully dedicated himself to sporting art. This genre, with its long and distinguished history in Britain, boasted masters like George Stubbs in the 18th century, renowned for his almost scientific studies of equine anatomy, and later, Victorian painters such as Sir Edwin Landseer, who, though broader in his animal subjects, captured the spirit of the British countryside. Lloyd stepped into this tradition, bringing his own unique perspective and skill.

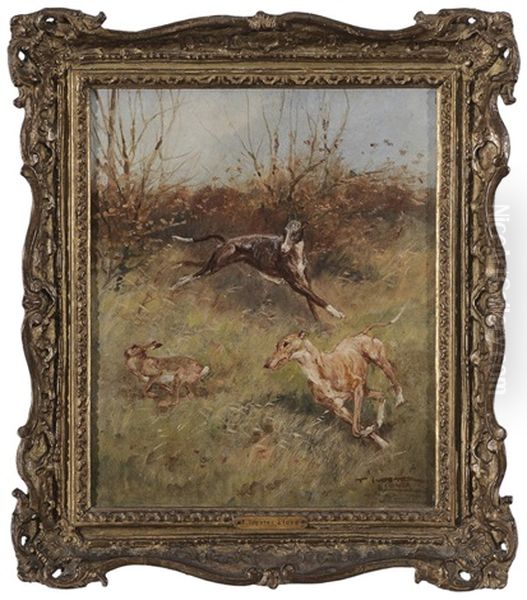

His primary subjects were the quintessential elements of British sporting life: fox hunting, beagling, horse racing, and polo. He possessed an exceptional ability to convey the energy and dynamism of these activities. In his hunting scenes, hounds are often depicted in full cry, their bodies extended in motion, while horses and riders navigate the terrain with a palpable sense of urgency and excitement. He didn't just paint animals; he painted their spirit and the environment they inhabited. His understanding of the nuances of the chase – the body language of the hounds, the focused intensity of the horses, the postures of the riders – lent an authenticity to his work that resonated with enthusiasts of these sports.

Master of Equine and Canine Form

A distinguishing feature of Thomas Ivester Lloyd's art is his meticulous attention to anatomical detail. His horses are not generic representations but individuals, their musculature, bone structure, and even their expressions rendered with precision. This accuracy was undoubtedly a product of his rigorous training at the Slade and his countless hours of direct observation. He understood the subtle shifts in weight and balance that defined a horse's gait, whether at a canter, a gallop, or clearing a fence. This anatomical fidelity is reminiscent of the dedication shown by earlier masters like George Stubbs, who famously dissected horses to understand their physiology, or the French animalier Rosa Bonheur, whose powerful depictions of animals were also grounded in careful study.

Similarly, his portrayal of hounds, whether foxhounds or beagles, was exemplary. He captured their lean, athletic forms, their keen expressions, and their collective energy as a pack. Each hound, while part of a group, often retained a sense of individuality. This ability to depict animals with both accuracy and character set him apart. His contemporaries in the sporting art field, such as Sir Alfred Munnings, Lionel Edwards, and Cecil Aldin, each had their own distinctive styles, but Lloyd's strength lay in his consistent, detailed realism combined with a fluid sense of movement.

A Prolific Illustrator

Beyond his paintings in oil and watercolor, Thomas Ivester Lloyd was also a highly accomplished and prolific illustrator. His work frequently graced the pages of popular British periodicals, including Punch, The Illustrated London News, and The Sketch. Illustration in this era was a vital medium for disseminating art to a wider public, and sporting subjects were particularly popular. Lloyd's illustrations, often pen and ink or wash drawings, retained the dynamism and accuracy of his paintings.

He also illustrated numerous books, particularly those focused on hunting, horses, and country life. These illustrations were not mere decorations but integral components of the narratives, bringing the text to life with vivid imagery. His ability to capture a scene or a character in a few well-chosen lines made him a sought-after illustrator. This aspect of his career places him in the company of other great British illustrators of the period, though their subject matter might have differed – artists like Arthur Rackham or Edmund Dulac were enchanting audiences with fantasy, while Lloyd was grounding them in the realities of the field and stable.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Thomas Ivester Lloyd's talent did not go unnoticed by the art establishment. He exhibited his work regularly at prestigious venues, a key measure of success for artists of his time. He showed paintings at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, a significant achievement that placed his work before a discerning national audience. He also exhibited at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, his city of birth.

His participation in these exhibitions indicates that his work was well-regarded by his peers and by art critics who valued skilled representational painting. While the art world was increasingly captivated by Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the burgeoning modernist movements, there remained a strong appreciation for traditional craftsmanship and subjects rooted in British life. Lloyd's consistent presence in these exhibitions underscores his standing within this segment of the art community.

Representative Works and Artistic Style

Identifying specific "masterpieces" for Thomas Ivester Lloyd can be challenging, as much of his work was commissioned or sold directly to private collectors and sporting enthusiasts. However, his oeuvre is characterized by recurring themes and a consistent style. Titles like "The Kill," "Gone Away," "Full Cry," or "Hounds Breaking Cover" are typical of his hunting scenes, each capturing a distinct moment of the chase with vigor and precision. His depictions of racehorses would often focus on the tension before the start or the thundering energy of the finish.

His style can be described as realistic and dynamic. He employed a confident, fluid line, particularly in his drawings and watercolors, which effectively conveyed movement. His oil paintings often had a richer, more textured quality, but always with a clear focus on the accurate rendering of his subjects. His color palette was generally naturalistic, reflecting the hues of the British countryside – the greens and browns of the fields and woodlands, the varied coats of horses and hounds, and the scarlet of hunting jackets. Unlike the Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who were exploring the fleeting effects of light and color, Lloyd's use of color was more descriptive, serving to enhance the realism of the scene.

He had a particular skill for composing complex scenes with multiple figures – human and animal – without sacrificing clarity or a sense of order. The pack of hounds, for instance, would be depicted as a cohesive unit, yet individual animals would often be discernible, each playing its part in the overall drama. This compositional skill, combined with his anatomical knowledge, made his sporting scenes particularly compelling.

Contemporaries in Sporting Art

Thomas Ivester Lloyd worked during a golden age for British sporting art. He was a contemporary of several other notable artists who specialized in similar themes, each with their unique approach. Sir Alfred Munnings (1878-1959) is perhaps the most famous of these, known for his vibrant, impressionistic depictions of horse racing, hunts, and rural life. While Munnings often used bolder colors and a looser brushwork, both he and Lloyd shared a deep love and understanding of the horse.

Lionel Edwards (1878-1966) was another prominent figure, celebrated for his atmospheric hunting scenes and his ability to capture the British landscape in all its moods. Cecil Aldin (1870-1935) was known for his charming and often humorous depictions of dogs, hunts, and coaching scenes, his style characterized by bold outlines and flat areas of color. "Snaffles" (Charles Johnson Payne, 1884-1967) created iconic, often witty, sporting prints with a distinctive, somewhat stylized approach. Gilbert Holiday (1879-1937) was another artist known for his dynamic equestrian scenes, particularly polo and racing, and also produced notable work as a war artist.

These artists, while sometimes in friendly competition, collectively contributed to a vibrant artistic milieu. They catered to a clientele passionate about country sports, and their work adorned the walls of stately homes, country clubs, and sporting lodges. Lloyd's place within this group is secured by his consistent quality, his anatomical precision, and his ability to convey the inherent drama of the sporting field. One might also look to earlier artists like John Frederick Herring Sr. for their influence on the tradition Lloyd inherited.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Thomas Ivester Lloyd passed away in 1942. His legacy is that of a dedicated and highly skilled chronicler of British sporting life. In an era that saw the decline of the horse's practical role in society with the rise of mechanization, Lloyd's art celebrated its enduring importance in sport and leisure. His paintings and illustrations serve as more than just aesthetically pleasing images; they are historical documents, capturing the customs, attire, and spirit of a particular time and social stratum.

The appeal of his work endures, particularly among those who appreciate traditional sporting art and fine animal portraiture. His paintings and prints are still sought after by collectors. The accuracy of his depictions means his work remains relevant to those involved in equestrian sports today, as the fundamental forms and movements of horses and hounds have not changed. His art evokes a sense of nostalgia for a certain vision of the English countryside, one characterized by open fields, spirited hunts, and a deep connection between humans and animals.

While he may not have been an artistic revolutionary in the mold of the continental modernists, his dedication to his chosen genre and the skill with which he executed his work ensure his place in the annals of British art. He represents a strand of artistic practice that valued keen observation, technical proficiency, and a deep engagement with the subject matter.

Conclusion

Thomas Ivester Lloyd was an artist who knew his subjects intimately. His life's work was a testament to his passion for the equestrian world and the traditions of British sporting life. From the formal training at the Slade School to his experiences in military service, and through his prolific output as a painter and illustrator, he consistently demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture the essence of his animal subjects – their power, grace, and vitality. His paintings and illustrations offer a window into a world where the horse was king and the call of the hunting horn echoed across the countryside. Alongside contemporaries like Munnings, Edwards, and Aldin, Thomas Ivester Lloyd helped to define British sporting art in the early 20th century, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be admired for its skill, authenticity, and evocative power. His art remains a tribute to the enduring bond between humans and animals, and to the timeless allure of the chase and the field.