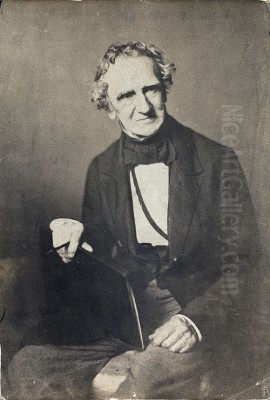

Thomas Sully stands as one of the most prominent and prolific portrait painters in nineteenth-century America. Born in England but spending the vast majority of his life and career in the United States, Sully bridged the gap between the stately portraiture of the Federal era and the burgeoning Romanticism of the mid-century. His elegant style, technical facility, and ability to capture a sense of grace and refinement made him highly sought after by the elite of American society, leaving behind a rich visual record of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Thomas Sully was born on June 19, 1783, in Horncastle, Lincolnshire, England. His parents, Matthew and Sarah Sully, were actors, and the theatrical world likely provided an early exposure to visual presentation and character. Seeking better opportunities, the Sully family emigrated to the United States in 1792, settling in Charleston, South Carolina, a vibrant cultural center in the post-Revolutionary South.

Young Thomas showed an early aptitude for art. Around the age of 12, he began his artistic training, initially receiving instruction in miniature painting from his brother-in-law, Jean Belzons, a French miniaturist. Following Belzons's departure, Sully moved to Richmond, Virginia, around 1799 to study with his elder brother, Lawrence Sully (c. 1769-1803), who was also a miniaturist and device painter. This early focus on miniature painting likely honed his attention to detail and likeness.

After Lawrence's untimely death in 1803, Thomas Sully briefly worked in Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia. A significant personal development occurred in 1805 when he married his brother's widow, Sarah Annis Sully. This union would prove lasting, and together they raised a large family, including Lawrence's children and nine of their own. This period saw Sully begin to transition from miniatures to larger oil portraits, seeking to establish himself more broadly as an artist.

Formative Years: Boston and London

Seeking to refine his skills and learn from established masters, Sully made a pivotal trip to Boston in 1807. His primary goal was to meet and observe the preeminent American portraitist of the era, Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828). While Stuart was famously guarded about his techniques, Sully managed to gain valuable insights by watching him paint and receiving critiques. Stuart's advice and example were influential, though Sully would ultimately develop a distinct style.

Recognizing the need for further formal training, particularly exposure to the European academic tradition, Sully resolved to travel to London. Friends and patrons in Philadelphia, where he had moved in 1808, helped finance his journey. He arrived in London in 1809 and remained for about a year. This period was transformative for his artistic development.

In London, Sully sought out the guidance of Benjamin West (1738-1820), the esteemed American expatriate painter who served as President of the Royal Academy. West provided encouragement and access to the artistic resources of London. However, the most profound influence on Sully's mature style came from Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the leading British portrait painter of the Regency era. Sully deeply admired Lawrence's fluid brushwork, elegant compositions, and flattering, romanticized depictions of his sitters, particularly women. He assiduously studied and copied Lawrence's work, absorbing the grace and sophistication that would become hallmarks of his own portraiture.

Philadelphia: The Center of a Flourishing Career

Upon his return from London in 1810, Sully settled permanently in Philadelphia, which would remain his home base for the rest of his long life. Philadelphia was then a major artistic and cultural hub in the United States, and Sully quickly established himself as its leading portrait painter, effectively succeeding Gilbert Stuart who had moved back to Boston.

His studio became a magnet for the city's elite and prominent figures from across the nation. He possessed a congenial manner and a remarkable ability to put his sitters at ease, capturing not just a likeness but also an air of fashionable elegance and inner sensibility. His reputation grew rapidly, built on his technical skill, his sophisticated London training, and his talent for creating portraits that were both accurate and appealingly idealized.

Throughout his career, Sully was incredibly productive. He maintained a detailed register of his works, listing over 2,600 paintings between 1801 and 1872. The vast majority of these were portraits, but he also produced historical scenes, landscapes, and "fancy pictures" – idealized genre scenes often featuring sentimental or romantic themes. His success allowed him to build a substantial home and studio on Fifth Street in Philadelphia.

Artistic Style and Technique

Thomas Sully's style is firmly rooted in the Anglo-American Romantic tradition. His greatest debt is to Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose influence is evident in Sully's fluid, painterly brushwork, rich color harmonies, and emphasis on graceful poses and flowing drapery. Sully excelled at capturing the textures of fabrics – silks, velvets, and lace – adding to the sense of luxury and refinement in his portraits.

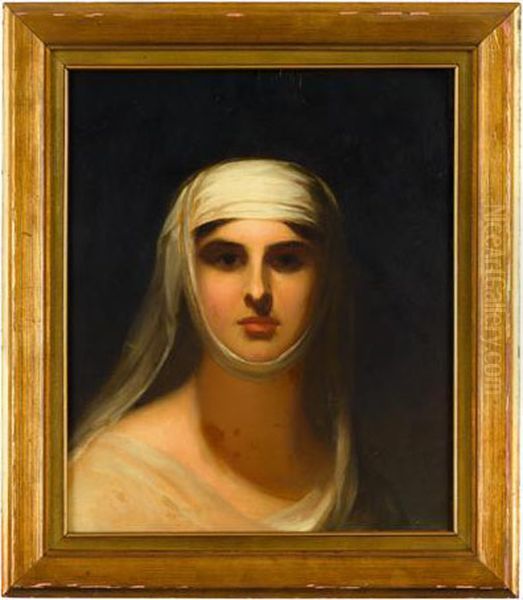

He particularly shone in his depictions of women and children. He rendered female sitters with an idealized grace, often emphasizing delicate features, luminous skin, and expressive eyes. His portraits convey a sense of sensitivity, charm, and social poise that resonated with the tastes of the era. His paintings of children, such as the famous The Torn Hat (1820), depicting his son Thomas Wilcocks Sully, possess a remarkable freshness and naturalism, capturing youthful innocence with tenderness.

While influenced by Lawrence, Sully adapted the style to an American context. His work is generally less flamboyant and perhaps more restrained than that of his British counterpart. Compared to the more robust, psychologically penetrating portraits of Gilbert Stuart, Sully's work often appears softer, more idealized, and focused on capturing social grace rather than intense character analysis. Some critics have noted that his portraits of men can sometimes lack the vigor and individuality found in his female portraits, occasionally leaning towards a formulaic elegance.

Sully employed a technique involving thin glazes of color over a carefully prepared underdrawing, allowing for subtle transitions and a luminous quality, especially in flesh tones. He paid close attention to composition, often using dynamic poses and rich backgrounds to enhance the sitter's presence. His use of light and shadow could be dramatic, contributing to the romantic mood of his best works.

Major Subjects and Patrons

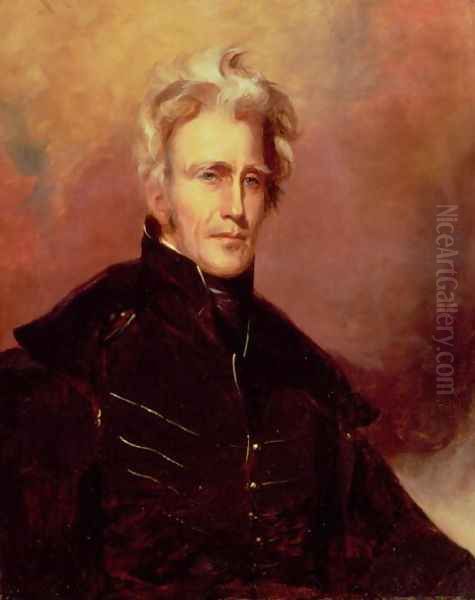

Sully's clientele included some of the most important figures of his time. He painted numerous presidents, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Andrew Jackson (whom he painted several times, capturing the general's formidable presence). He also portrayed military heroes like Commodore Stephen Decatur and General Winfield Scott.

A particularly significant commission came during the Marquis de Lafayette's celebrated return tour of the United States in 1824-1825. Sully was chosen to paint the aging Revolutionary War hero for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, creating a powerful full-length portrait that captured the historical significance of the occasion.

Beyond political and military figures, Sully was the portraitist of choice for wealthy merchants, society matrons, intellectuals, and fellow artists in Philadelphia and other major cities like Baltimore, Washington D.C., and New York. His ability to convey status and refinement made him highly desirable among those wishing to commemorate their position in society. He painted members of prominent families such as the Biddles, Cadwaladers, and Ridgelys.

Iconic Works

Several of Thomas Sully's paintings have become iconic images in American art history.

Queen Victoria (1838): Perhaps his most famous international commission, Sully traveled to London to paint the young queen shortly after her coronation. Commissioned by the St. George's Society of Philadelphia, the resulting full-length portrait captures Victoria's youthful dignity and the splendor of her office. It remains one of the defining images of the monarch in her early reign.

The Passage of the Delaware (1819): Housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, this large historical painting depicts George Washington leading his troops across the icy river before the Battle of Trenton. While overshadowed in popular imagination by Emanuel Leutze's later, more dramatic version, Sully's work is a significant example of American history painting from the period, showcasing his ambition beyond portraiture.

The Torn Hat (1820): This intimate and informal portrait of his son Thomas is one of Sully's most beloved works. Its spontaneous feel, focus on light, and tender depiction of childhood make it a standout piece, anticipating later trends in genre painting. It resides in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Lady with a Harp: Eliza Ridgely (1818): This elegant portrait, now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., epitomizes Sully's skill in portraying graceful femininity and fashionable society. The subject, Eliza Ridgely of Hampton Plantation near Baltimore, is depicted with her harp in a composition that exudes refinement and musical sensibility.

The Gypsy Girl (or Spanish Gypsy Girl) (1839): Located at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), this "fancy picture" showcases Sully's romantic imagination. The dramatic lighting, rich colors, and evocative subject matter demonstrate his ability to create compelling narrative images beyond straightforward portraiture.

Other notable works include portraits of Ann Hopple Biddle (c. 1818) and Angela K. Cleary (c. 1830s), both exemplifying his elegant style in female portraiture. His numerous portraits of Andrew Jackson also stand as important contributions to American iconography.

The London Commission: Painting Queen Victoria

The commission to paint Queen Victoria in 1838 marked a pinnacle in Sully's career. Funded by the Society of the Sons of St. George in Philadelphia, an organization of Englishmen and their descendants, Sully traveled to London specifically for this purpose. He secured several sittings with the young Queen at Buckingham Palace, meticulously sketching her likeness and noting details of her coronation robes.

The experience was documented in Sully's journal, providing insights into the process and his interactions with the monarch. He aimed to create a portrait that conveyed both her regal status and her youthful charm. The finished full-length painting was a triumph, widely praised upon its exhibition in Philadelphia. It cemented Sully's international reputation and remains one of his most celebrated works, showcasing his mastery of the grand manner portrait influenced by Lawrence. He painted several versions and studies related to this commission.

Beyond Portraiture: Historical and Fancy Pictures

While portraiture formed the core of his output and income, Sully harbored ambitions in other genres, particularly history painting, which was considered the highest form of art in the academic tradition. His most notable effort in this area is The Passage of the Delaware (1819). Although a significant undertaking, large-scale history painting proved difficult to sustain financially in America at the time, lacking the state or church patronage common in Europe.

Sully also frequently painted "fancy pictures." These were often idealized depictions of literary characters, allegorical figures, or charming genre scenes, frequently featuring beautiful women or children. Works like The Gypsy Girl fall into this category. These paintings allowed Sully more freedom for imagination and sentiment than commissioned portraits and proved popular with collectors. They demonstrate his engagement with the broader Romantic movement's interest in emotion, exoticism, and storytelling.

Sully as Educator and Mentor

Thomas Sully played an important role in the artistic life of Philadelphia beyond his own painting. He was deeply involved with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the oldest art institutions in America. He served as a director there for many years (though perhaps not the fifteen consecutive years sometimes cited, his involvement was long and significant) and was instrumental in shaping its early collections and exhibitions.

He was also a generous mentor to younger artists. His studio served as a training ground, and he offered advice and encouragement to aspiring painters. Among those who studied with him or were significantly influenced by him was John Neagle (1796-1865), who became a prominent Philadelphia portraitist in his own right and eventually married Sully's stepdaughter Mary. Jacob Eichholtz (1776-1842), a Lancaster, Pennsylvania painter, also benefited from Sully's guidance. Sully's influence extended through his students and the widespread admiration for his style.

Late in his life, Sully compiled his thoughts on technique into a manuscript titled Hints to Young Painters. Although not published until after his death, it provides valuable insights into his methods and the practices of early 19th-century portrait painting.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Sully operated within a rich artistic landscape. In America, his contemporaries included the aging masters of the Federal era like Gilbert Stuart and the prolific Peale family, including Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) and his son Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860). He also worked alongside other prominent portraitists such as John Vanderlyn (1775-1852), Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872, before focusing on the telegraph), Chester Harding (1792-1866), and Henry Inman (1801-1846). History painters like John Trumbull (1756-1843) and Washington Allston (1779-1843) were also part of this milieu.

His connection to the British school remained strong throughout his career. His style constantly invites comparison with Sir Thomas Lawrence, but also relates to the work of earlier British portraitists like George Romney (1734-1802) and John Hoppner (1758-1810), and Scottish master Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823), known for his elegant characterizations. Sully's friend Charles Robert Leslie (1794-1859), another American artist who found success in London, shared a similar artistic orbit. Sully's partner in a short-lived Philadelphia art gallery venture, James S. Earle, further illustrates his integration into the commercial and social aspects of the art world.

Personal Life

Thomas Sully appears to have been a respected and well-liked figure in Philadelphia society. He was known for his gentlemanly demeanor and professionalism. His marriage to Sarah Annis Sully was enduring, lasting over sixty years until her death in 1867. Together they managed a large household filled with children – both Sarah's from her marriage to Lawrence, and their own nine offspring. Several of Sully's children also became artists, including Thomas Wilcocks Sully, Jane Cooper Sully (who married John Neagle), and Blanche Sully.

Beyond his art, Sully was involved in the cultural life of Philadelphia. He was one of the founders of the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia in 1820, reflecting a broad interest in the arts. His detailed record-keeping, not only of his paintings but also his daily affairs, provides historians with a valuable window into the life of an artist in 19th-century America. The erroneous story sometimes circulated about his wife Sarah being murdered in 1800 is incorrect; she lived a long life alongside him.

Later Years and Legacy

Thomas Sully remained active as a painter well into his old age, continuing to take commissions and add entries to his painting register almost until his death. He witnessed significant changes in American art, including the rise of photography, which began to challenge the dominance of painted portraiture, as well as the emergence of new artistic styles like the Hudson River School in landscape painting.

He died in Philadelphia on November 5, 1872, at the venerable age of 89. He was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery, a historic cemetery overlooking the Schuylkill River. His funeral was attended by many friends and colleagues, testament to the high regard in which he was held.

Thomas Sully's legacy rests on his mastery of Romantic portraiture. He successfully adapted the elegant British style of Sir Thomas Lawrence for an American audience, creating a body of work characterized by grace, technical fluency, and sensitivity. For decades, he was the preeminent portrait painter in Philadelphia and one of the most sought-after artists in the nation. His paintings provide an invaluable visual record of the prominent figures and social elite of the Jacksonian era and beyond. While tastes in art evolved, Sully's contribution remains significant, representing a key moment in the development of American painting and capturing the aspirations and sensibilities of his time with enduring charm and skill. His works are held in major museums across the United States and abroad, ensuring his continued recognition as a central figure in American art history.