Allan Ramsay stands as one of the most significant and accomplished portrait painters of the eighteenth century in Britain. Born into the vibrant intellectual milieu of Enlightenment Edinburgh, he forged a distinct artistic identity, blending the grace of continental European styles with a uniquely British sensibility for character and naturalism. His career spanned the dynamic period from the late Baroque to the rise of Neoclassicism, positioning him as a pivotal figure whose work was sought after by intellectuals, aristocrats, and royalty alike. While often compared to his London contemporaries, particularly Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, Ramsay cultivated a style marked by its elegance, psychological acuity, and exquisite technique, securing his place as Scotland's foremost painter of the era and a major contributor to the story of British art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Allan Ramsay was born in Edinburgh on October 13, 1713. He was the eldest son of his namesake, Allan Ramsay (1686-1758), a highly regarded poet, playwright, publisher, and cultural figure central to the early Scottish Enlightenment. This familial connection undoubtedly immersed the young Ramsay in a world of literature, intellectual debate, and artistic appreciation from an early age, fostering the cultivated mind that would later distinguish him among his fellow artists. His father's prominence likely provided valuable social connections as the younger Ramsay embarked on his own career.

His initial artistic training took place in Edinburgh, possibly involving sessions at the short-lived Academy of St Luke, founded by Richard Cooper the Elder around 1729. Seeking more advanced instruction, Ramsay travelled to London around 1733. There, he studied for a time under the Swedish painter Hans Hysing, a competent portraitist working in the established Kneller tradition but perhaps lacking significant innovative flair. More importantly, Ramsay attended the St Martin's Lane Academy, a crucial hub for artists in London before the founding of the Royal Academy. This informal but vital institution, associated with figures like William Hogarth, provided opportunities for life drawing and interaction with other aspiring artists, exposing Ramsay to the latest artistic currents in the capital.

Recognizing the necessity of firsthand exposure to the masterpieces of European art, Ramsay embarked on the Grand Tour, travelling to Italy in 1736. He spent approximately two years primarily in Rome and Naples, immersing himself in the study of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian masters. During this formative period, he received instruction from Francesco Imperiali in Rome and, more significantly, from the celebrated Neapolitan painter Francesco Solimena. Solimena, a leading figure of the late Baroque, was renowned for his dramatic compositions and rich colour. His influence, along with the general atmosphere of Italian art, imbued Ramsay's developing style with a sense of grace, fluidity, and sophisticated handling of paint that would set him apart from many of his British contemporaries.

Forging a Career in Scotland and London

Returning to Britain around 1738, Ramsay initially established himself in Edinburgh. His Italian training and refined manner quickly attracted attention. An early significant commission was the portrait of Duncan Forbes of Culloden, Lord President of the Court of Session, a work demonstrating his growing confidence and skill. His full-length portrait of Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll, one of Scotland's most powerful figures, further cemented his reputation north of the border. These successes provided a strong foundation, but the larger artistic market and greater opportunities for patronage lay in London.

By 1739, Ramsay had moved to London, establishing a studio and entering the competitive world of metropolitan portraiture. He arrived at a time when the dominant style was still largely influenced by Sir Godfrey Kneller, though artists like Hogarth were challenging conventions. Ramsay's elegant, continental manner offered a fresh alternative. He soon found influential patrons, including the Duke of Bridgewater and, crucially, John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute. Lord Bute, a fellow Scot with significant political influence, especially after the accession of George III, would become one of Ramsay's most important supporters.

In London, Ramsay faced competition from established figures like Thomas Hudson, who notably was the master of the young Joshua Reynolds. As Reynolds himself returned from Italy in the early 1750s and began popularising the 'Grand Manner' derived from classical and Renaissance art, a rivalry, or at least a stylistic counterpoint, developed between him and Ramsay. While Reynolds often aimed for heroic or allegorical representations, Ramsay generally favoured a more intimate, naturalistic approach, focusing on subtle characterisation and refined execution.

The Ramsay Style: Elegance and Insight

Allan Ramsay's mature style is characterised by its distinctive blend of elegance, sensitivity, and technical finesse. He absorbed lessons from Italian Baroque and French Rococo art, adapting them to British tastes. Unlike the often robust or dramatic approach of some contemporaries, Ramsay's work typically exudes a sense of calm restraint and understated sophistication. His drawing was precise yet fluid, providing a solid foundation for his delicate handling of paint.

A key feature of Ramsay's art is his mastery of colour and light. He often employed a palette favouring soft, harmonious tones – silvery greys, pale blues, rose pinks, and creamy whites – applied with a light, feathery touch that particularly suited the depiction of female sitters and luxurious fabrics. His rendering of textures, especially silks, satins, and lace, was exceptionally skilful, contributing significantly to the overall impression of refinement. This sensitivity to surface and subtle modulation of colour perhaps shows an affinity with French Rococo painters like Jean-Marc Nattier, whose portraits of court ladies were renowned for their charm and delicate execution. Some critics have even noted a kinship with the pastel-like effects achieved by artists such as Maurice Quentin de La Tour, translated into the medium of oil.

Beyond the surface elegance, Ramsay possessed a remarkable ability for psychological penetration. He excelled at capturing not just a likeness, but the personality and inner life of his sitters. His portraits often convey a sense of quiet introspection or gentle animation. He avoided the overt theatricality sometimes found in Reynolds's work, preferring poses and expressions that felt natural and uncontrived. This focus on individual character aligned well with the values of the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement with which Ramsay was deeply connected. His portraits of thinkers like David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are compelling examples of his ability to portray intellectual weight and complex personality.

Compared to William Hogarth, another giant of the era, Ramsay's focus was different. Hogarth often used portraiture as part of a larger narrative or satirical aim, embedding his sitters within detailed social contexts. Ramsay, while sensitive to social standing, concentrated more purely on the individual, seeking a timeless elegance and capturing the nuances of human presence. His approach represented a sophisticated fusion of observation and idealisation, resulting in portraits that were both flattering and convincingly real.

The Grand Tour's Enduring Spell

The allure of Italy remained strong for Ramsay. He undertook a second extended visit from 1754 to 1757. This trip seems to have deepened his engagement with classical art and the High Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael. He spent time drawing from the antique and associating with other artists in Rome, including Pompeo Batoni, a leading portraitist who catered to the Grand Tour clientele. This period likely reinforced the classical underpinning of Ramsay's art, refining his sense of form and composition, perhaps adding a greater degree of solidity and gravitas to his work, complementing the Rococo grace he had already mastered.

These Italian journeys were not merely about technical study; they were integral to Ramsay's identity as a cultivated, cosmopolitan artist. His fluency in Italian and French, combined with his deep knowledge of classical literature and art history, distinguished him socially and intellectually. This worldliness informed his art, allowing him to connect with the sophisticated tastes of his patrons, many of whom had also undertaken the Grand Tour. Italy provided Ramsay with a continuous source of inspiration and a benchmark for artistic excellence throughout his career.

Painter to the Court

The accession of King George III in 1760 marked a turning point in Ramsay's career. The new king, unlike his predecessors, was keenly interested in the arts and sciences and determined to patronise British talent. Ramsay's connection to Lord Bute, who became the King's tutor and later Prime Minister, proved highly advantageous. George III admired Ramsay's refined and less ostentatious style compared to some other painters.

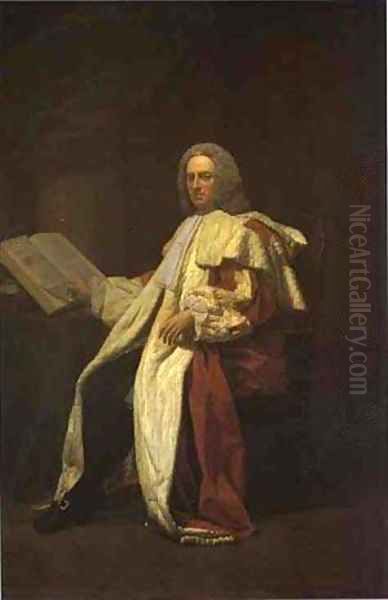

Ramsay was commissioned to paint the official state portraits of the King and his new bride, Queen Charlotte, shortly after their marriage in 1761. These coronation portraits, depicting the monarchs in their magnificent robes, were highly successful. They established a pattern for royal imagery that was both regal and relatively approachable, reflecting the personal style of the new King and Queen. Ramsay's ability to combine formality with a sense of human presence appealed greatly to the royal couple.

In 1767, Ramsay achieved the pinnacle of official artistic recognition in Britain when he was appointed Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King, succeeding John Shackleton. This prestigious position brought considerable honour and a steady stream of royal commissions, but it also came with burdens. The demand for replicas of the state portraits, required for embassies, colonial governors, and institutions across the expanding British Empire, was enormous. While lucrative, this repetitive work increasingly occupied Ramsay's studio and likely limited his time for more creative or varied commissions.

Masterpieces and Notable Sitters

Throughout his career, Allan Ramsay produced numerous portraits that are now considered masterpieces of British art. Among the most celebrated is the Portrait of the Artist's Wife, Margaret Lindsay of Evelick (c. 1758-60). This tender and intimate depiction shows his second wife arranging flowers. The painting is admired for its exquisite handling of paint, particularly the delicate rendering of the lace fichu and the subtle play of light on her features. It conveys a sense of warmth and affection, standing as one of the most personal and beautiful portraits of the eighteenth century.

His portraits of leading Enlightenment figures are also highly significant. The Portrait of David Hume (1766) presents the philosopher in a simple, direct manner, clad in sober red attire. Ramsay captures Hume's renowned intellect and perhaps a hint of his scepticism, focusing entirely on the power of the sitter's presence without distracting background elements. Similarly, his Portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1766), painted during the philosopher's brief and tumultuous stay in England as a guest of Hume, is a fascinating study. Depicting Rousseau in his distinctive Armenian costume, Ramsay captures the intense, perhaps troubled, nature of the influential thinker.

The royal portraits, despite the demands of replication, include some outstanding works. The original coronation portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte (c. 1761-62) possess a freshness and refinement. A particularly charming example of his royal work is the Portrait of Queen Charlotte with her Two Eldest Sons (c. 1764), which combines regal elegance with a sense of maternal warmth.

Beyond these famous examples, Ramsay painted many leading figures of the day. His patrons included aristocrats like Lord Bute, intellectuals such as the physician Dr. William Hunter, and society figures like the sharp-witted bluestocking Lady Mary Coke. He also painted Augusta, Princess of Wales, the King's mother. Each portrait, at its best, demonstrates Ramsay's consistent ability to tailor his approach to the individual, creating likenesses that were both elegant and insightful.

The Workshop and Collaboration

Like most successful portraitists of the era, especially those with royal appointments, Allan Ramsay operated a busy studio and relied on assistants to meet demand. The production of numerous replicas, particularly of the state portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte, necessitated a well-organized workshop. While Ramsay would typically paint the head and perhaps sketch the overall composition, assistants were often employed to paint the drapery, backgrounds, and create copies under his supervision.

Several talented artists worked as Ramsay's assistants at various times. David Martin, a fellow Scot, was a long-serving and capable assistant who later established his own successful career as a portrait painter and engraver. Philip Reinagle also worked in Ramsay's studio before developing his own specialisation in animal painting and landscapes. The use of assistants was standard practice, but it inevitably led to variations in quality, with studio copies sometimes lacking the finesse and sensitivity of works entirely by Ramsay's own hand. Nonetheless, the Ramsay studio maintained a high standard, ensuring that the official image of the monarchy disseminated through these portraits was one of consistent elegance and dignity.

The Man of Letters

Allan Ramsay was more than just a painter; he was a true product of the Enlightenment, a man of considerable intellectual breadth and learning. His upbringing in his father's literary circle, his classical education, and his extensive travels equipped him with wide-ranging interests. He was fluent in several languages, including Latin, Greek, French, and Italian, and possessed a deep knowledge of literature and history.

He was an active participant in the intellectual life of both Edinburgh and London. In Scotland, he was a member of the Select Society, a prestigious discussion group whose members included David Hume, Adam Smith, William Robertson, and other luminaries of the Scottish Enlightenment. In London, he moved in learned circles and enjoyed friendships with figures like Dr. Samuel Johnson (though Johnson famously expressed a preference for Reynolds's art), and maintained connections with continental intellectuals, possibly including the French philosopher Denis Diderot.

Ramsay occasionally put his thoughts into writing. He published pamphlets on political matters and engaged in debates about taste and aesthetics, such as his Dialogue on Taste (1762). His intellectual pursuits distinguished him from artists like Thomas Gainsborough, who was known for his more intuitive and less theoretical approach to art. Ramsay's combination of artistic talent and scholarly erudition made him a respected figure, embodying the Enlightenment ideal of the cultivated individual. This intellectual depth undoubtedly informed his portraiture, enabling him to engage with his sitters on multiple levels and capture the nuances of their character and status.

Winding Down and Legacy

Around 1773, Ramsay suffered a serious injury to his right arm, which significantly curtailed his ability to paint. Although he seems to have undertaken some work after this, his prolific output effectively ceased. Increasingly, he devoted his time to his intellectual interests, conversation, and travel. He made further trips to his beloved Italy between 1775 and 1777, and again from 1782, seeking health benefits and continuing his studies.

It was while returning from his final Italian journey that Allan Ramsay died in Dover on August 10, 1784, at the age of 70. He was buried in St Marylebone Churchyard in London.

In the decades following his death, Ramsay's reputation was somewhat overshadowed by the towering figures of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, and the brilliantly fluid Thomas Gainsborough. Reynolds's theoretical writings and institutional power, along with Gainsborough's dazzling brushwork, captured the attention of subsequent generations. However, Ramsay's unique contribution never entirely faded. Connoisseurs continued to admire the quiet elegance and psychological depth of his work.

A significant reassessment of Ramsay's importance began in the twentieth century, spearheaded by the art historian Alastair Smart, whose research and publications brought renewed attention to the quality and significance of Ramsay's oeuvre. Today, Ramsay is recognised as a key figure in the development of British portraiture. He successfully integrated continental elegance with British taste for naturalism, creating a style that was both sophisticated and sensitive.

His influence can be seen in the work of his assistants, like David Martin, and arguably in the development of later Scottish portraiture, particularly in the work of Sir Henry Raeburn, who brought a new boldness but shared a similar focus on character. Ramsay stands apart from Reynolds's Grand Manner and Gainsborough's flickering immediacy, offering a third way – a path defined by refined drawing, delicate colour, subtle observation, and an intimate connection with the ideals of the Enlightenment. His best portraits remain compelling testaments to his skill and sensitivity, securing his place as one of Britain's most accomplished and intelligent painters.

Conclusion

Allan Ramsay's career represents a remarkable synthesis of artistic talent, intellectual curiosity, and cultural engagement. Emerging from the Scottish Enlightenment, trained in London and Italy, he developed a distinctive style of portraiture characterised by elegance, sensitivity, and profound psychological insight. He navigated the competitive London art world with success, culminating in his appointment as Principal Painter to George III, a role that placed him at the centre of British cultural life.

While fulfilling the demands of royal patronage, he created intimate masterpieces, particularly his portraits of women and intellectuals, which reveal his exceptional skill in capturing both external likeness and inner character. His work provides a refined counterpoint to the more robust styles of Reynolds or Hogarth, showcasing the influence of French Rococo grace tempered by a British preference for naturalism. As a man of letters and a friend to leading thinkers of his age, Ramsay embodied the Enlightenment ideal. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful and insightful paintings but also in his role as a bridge between Scottish and English culture, and between the worlds of art and ideas, leaving an indelible mark on the history of British portraiture.