Tiziano Vecellio, known to the English-speaking world simply as Titian, stands as one of the towering figures of the Italian Renaissance and arguably the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. His mastery of color, his profound psychological insight in portraiture, and his dynamic compositions across religious and mythological themes left an indelible mark on the course of Western art. Active for an exceptionally long and productive life, spanning roughly from 1488/1490 to 1576, Titian's influence stretched across Europe, captivating popes, emperors, and dukes, and inspiring generations of artists who followed.

Early Life and Venetian Formation

Titian was born in Pieve di Cadore, a small village nestled in the Dolomite mountains, part of the Republic of Venice. While the exact year of his birth remains debated by scholars, falling somewhere between 1488 and 1490, it is known he hailed from a family of some local standing. His father, Gregorio Vecellio, was a councillor and managed local mines. Recognizing young Tiziano's talent, his family sent him to Venice, the glittering capital of the Republic, around the age of ten to pursue an artistic apprenticeship.

Venice, a wealthy maritime power, offered a vibrant artistic environment distinct from Florence and Rome. Initially, Titian may have briefly studied with the mosaicist Sebastiano Zuccato before entering the workshop of the leading masters of the day. He trained under Gentile Bellini and later, more significantly, with Gentile's brother, Giovanni Bellini. Giovanni Bellini was then the most respected painter in Venice, known for his rich colors and atmospheric landscapes.

In Bellini's workshop, Titian would have learned the fundamentals of Venetian painting, particularly the emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) over disegno (drawing and design), which was paramount in Florence. He also worked alongside Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco), another brilliant young painter whose poetic style and enigmatic subjects deeply influenced Titian's early development. Their collaboration was so close that attributing certain works from this period, like the Pastoral Concert (now in the Louvre), remains a subject of scholarly discussion.

The Ascent of a Master

Giorgione's premature death from the plague in 1510, followed by Giovanni Bellini's passing in 1516, cleared the path for Titian to become the preeminent painter in Venice. He had already begun to establish his reputation, collaborating with Giorgione on frescoes for the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (the German merchants' warehouse) in 1508, though little of this work survives. His independent talent shone through in early works that combined Giorgione's lyrical mood with a growing dynamism and psychological depth.

A pivotal moment came with the unveiling of his monumental altarpiece, the Assumption of the Virgin (Assunta), for the high altar of the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in 1518. This dramatic, brilliantly colored work, depicting the Virgin Mary ascending to heaven amidst a swirl of apostles and angels, stunned contemporaries with its energy and scale. It firmly established Titian's reputation not just in Venice but internationally, marking a departure from the more static compositions of his predecessors and showcasing his command of complex figural arrangements and emotional intensity.

Following the Assumption, Titian was appointed the official painter of the Venetian Republic, succeeding Giovanni Bellini. This prestigious position brought him a regular salary and numerous state commissions, including battle paintings for the Doge's Palace (later destroyed by fire) and portraits of the ruling Doges. His workshop flourished, attracting assistants and handling a growing number of commissions from churches, confraternities, and private patrons.

The Language of Color and Brushstroke

Titian's art is synonymous with the Venetian mastery of color. He built up his paintings through layers of oil glazes, achieving unparalleled richness, depth, and luminosity. Unlike the Florentine emphasis on clear outlines and sculptural form, Titian often defined forms through modulations of color and light, allowing edges to soften and blend, creating a more atmospheric and visually unified effect. His brushwork became increasingly free and expressive throughout his career, particularly in his later years, where forms could dissolve into flickering strokes of paint that conveyed intense emotion and movement.

This painterly approach allowed Titian to render textures—sumptuous velvets, gleaming armor, soft flesh, and airy landscapes—with breathtaking realism. He understood the emotional power of color, using warm hues to convey passion and sensuality, deep blues and reds for religious solemnity, and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the narrative impact of his scenes. His technical innovations and expressive use of the oil medium profoundly influenced subsequent painters, from Peter Paul Rubens to Diego Velázquez.

Master of Portraiture

While excelling in all genres, Titian was perhaps the most sought-after portraitist of his era. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture not only the physical likeness of his sitters but also their personality, status, and inner life. His portraits moved beyond mere representation to become profound psychological studies. Early examples like the Man with a Glove show a Giorgionesque sensitivity, while later portraits reveal increasing confidence and insight.

He painted popes, emperors, kings, dukes, cardinals, writers, and Venetian nobles. His relationship with Emperor Charles V was particularly significant. Titian painted numerous portraits of the Emperor, including the iconic Equestrian Portrait of Charles V (Prado Museum), commemorating his victory at the Battle of Mühlberg. This work established a new standard for equestrian portraiture, conveying imperial power and stoic resolve. An often-repeated anecdote, possibly apocryphal but indicative of their relationship, tells of the Emperor picking up a dropped paintbrush for the artist, declaring, "Titian is worthy to be served by Caesar." Charles V rewarded Titian with honors, including knighting him as a Knight of the Golden Spur and making him a Count Palatine, granting him and his descendants noble status.

Other landmark portraits include the penetrating group portrait Pope Paul III and His Grandsons Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese, a complex study of power dynamics and aging, and his insightful depictions of his friend, the writer Pietro Aretino. Titian also painted several self-portraits, particularly in his later years, offering introspective glimpses of the aged master. His approach to portraiture, emphasizing character and using painterly techniques to suggest presence, deeply influenced artists like Rembrandt van Rijn, Anthony van Dyck, and Velázquez.

Religious Narratives

Titian brought the same dynamism and emotional depth to his religious paintings. Following the Assumption, he created another masterpiece for the Frari church, the Pesaro Madonna (1519-1526). This altarpiece revolutionized devotional painting with its diagonal composition, moving the Virgin and Child off-center and creating a more dynamic interaction between the sacred figures and the kneeling members of the Pesaro family. The rich colors, dramatic lighting, and sense of movement engage the viewer directly.

Throughout his career, Titian explored key Christian themes with profound humanity. Works like The Entombment of Christ (Louvre) convey deep pathos and grief through powerful figures and somber lighting. His Martyrdom of St. Lawrence is a dramatic night scene, illuminated by the flickering light of the gridiron and torches, showcasing his mastery of nocturnal effects.

In his final years, Titian worked on a deeply personal Pietà, intended for his own tomb chapel in the Frari. Left unfinished at his death, it depicts Nicodemus (likely a self-portrait) and Mary Magdalene mourning over the body of Christ in a dramatically lit, architecturally framed space. The loose, almost impressionistic brushwork and intense emotion make it a moving testament to his late style and enduring faith.

Mythological Visions: The 'Poesie'

Titian's mythological paintings are among his most celebrated works, renowned for their sensuality, drama, and masterful depiction of the nude figure within lush landscapes. An early triumph in this genre was Bacchus and Ariadne (National Gallery, London), painted for Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, as part of a series decorating his study. The painting captures the dynamic arrival of Bacchus and his ecstatic followers, startling Ariadne on the shore of Naxos.

Perhaps his most famous mythological works are the series of large-scale paintings known as the poesie (poetic inventions), commissioned by Philip II of Spain in the 1550s and early 1560s. Based on Ovid's Metamorphoses, these paintings explored themes of love, desire, betrayal, and divine power. The series included multiple versions of Danaë receiving Jupiter as a shower of gold, Venus and Adonis depicting the goddess's futile attempt to restrain her mortal lover from the hunt, the paired masterpieces Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto (National Galleries of Scotland/National Gallery, London), showing the tragic consequences of mortals encountering goddesses, and The Rape of Europa (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston), a dynamic portrayal of Europa carried off by Jupiter disguised as a bull.

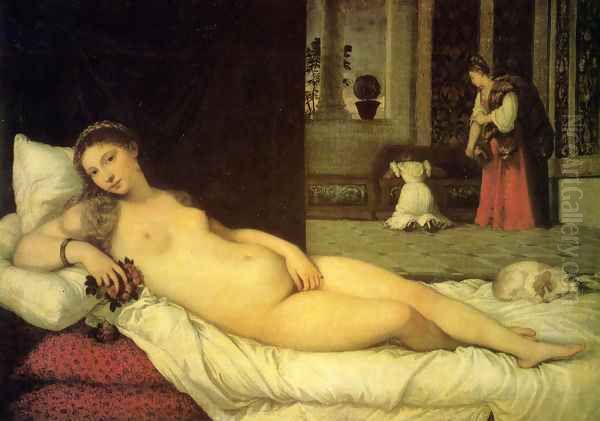

These poesie are celebrated for their rich color, fluid brushwork, and psychological complexity. They blend sensuous beauty with underlying tragedy, showcasing Titian's narrative skill and his ability to convey powerful emotions through the human form and its interaction with nature. The Venus of Urbino (Uffizi, Florence), though not part of the poesie, is another iconic mythological nude, a reclining Venus whose direct gaze and domestic setting have captivated and provoked viewers for centuries, influencing artists from Velázquez to Édouard Manet.

The Workshop and International Fame

Titian ran one of the most successful and organized workshops of the Renaissance. The sheer volume of commissions he received, especially from international patrons like Philip II, necessitated significant assistance. His assistants, including his own son Orazio Vecellio, helped prepare canvases, transfer designs, paint backgrounds or less critical areas, and produce replicas or variants of successful compositions under the master's supervision. This practice allowed Titian to meet the high demand for his work and spread his style widely.

While the exact roster of his pupils is debated, his workshop was a major center of Venetian art production. Younger contemporaries like Jacopo Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, while developing their own distinct styles and running competing large workshops, were undoubtedly aware of and responded to Titian's dominance and innovations. Titian's business acumen was also notable; he skillfully managed his patrons, negotiated fees, and invested his earnings, becoming quite wealthy. His fame was truly international, surpassing that of almost any artist before him.

Patrons and Contemporaries

Titian's career was shaped by his relationships with powerful patrons. Early support came from Venetian nobles and confraternities. His connection with Alfonso I d'Este of Ferrara led to commissions like Bacchus and Ariadne. Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, was another important patron. The Della Rovere family, Dukes of Urbino, commissioned the Venus of Urbino.

However, his most significant patrons were the Habsburg Emperor Charles V and his son, Philip II of Spain. These relationships secured Titian's international preeminence and resulted in many of his greatest masterpieces, from state portraits to the mythological poesie. He also worked for Pope Paul III and the Farnese family in Rome, though his primary base remained Venice.

Titian navigated a complex artistic world. He learned from Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione. He competed with contemporaries like Sebastiano del Piombo (who moved between Venice and Rome) and Lorenzo Lotto. In his later years, the dynamic energy of Tintoretto and the decorative splendor of Veronese presented new challenges within the Venetian scene. His relationship with the writer Pietro Aretino was crucial; Aretino acted as a friend, critic, and publicist, promoting Titian's work through his widely circulated letters, though sometimes criticizing the artist as well. While aware of the achievements of Central Italian masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, Titian largely pursued a distinctly Venetian path focused on color, light, and emotion.

The Late Style: A Visionary Intensity

In the last two decades of his life, Titian's style underwent a remarkable transformation. His brushwork became increasingly loose, bold, and expressive, sometimes applied with fingers as well as brushes. Forms seem to emerge from or dissolve into a turbulent atmosphere of color and light. The palette often darkened, punctuated by dramatic highlights. Works from this period, such as The Flaying of Marsyas (Kroměříž, Czech Republic), the late Self-Portrait (Prado), and the unfinished Pietà, possess an extraordinary emotional intensity and visionary quality.

This late style, sometimes described as "impressionistic" or proto-Baroque, baffled some contemporaries but has fascinated later generations. It represents a culmination of his lifelong exploration of the expressive possibilities of paint, prioritizing emotional impact and visual sensation over precise detail. These late works demonstrate Titian's undiminished creative power even in extreme old age and anticipate developments in painting centuries later.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Mysteries

Titian's long life and fame generated numerous stories and some ongoing debates. The precise date of his birth remains uncertain, impacting calculations of his age at death (ranging from the late 80s to potentially 90s). Giorgio Vasari, the Renaissance biographer, praised Titian highly but also contributed to some enduring narratives, including emphasizing a rivalry with Michelangelo.

The anecdote of Charles V and the paintbrush highlights his elevated status. Criticisms from figures like Aretino hint at the pressures and rivalries of the art world, accusing Titian at times of greed or slowness in completing commissions. Minor discrepancies, like the differing eye colors noted in some self-portraits or attributed works (Allegory of Prudence), add to the layers of interpretation surrounding his image.

In modern times, the high market value of his works has generated headlines, such as the joint acquisition of Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto by UK national galleries for substantial sums, underscoring their perceived cultural importance. Questions about workshop participation in certain paintings continue to be debated by scholars, refining our understanding of attribution. His personal life also faced tragedy; his wife Cecilia died relatively young in 1530 after bearing several children (including his painter son Orazio), and he outlived Orazio as well.

Death and Enduring Legacy

Titian died in Venice on August 27, 1576. The city was in the grip of a major plague epidemic, and while official records reportedly cited "fever," the plague is widely considered the likely cause of death. Unusually for a plague victim, he was granted burial within a church, the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, the very church housing his Assumption and Pesaro Madonna. His final, unfinished Pietà was likely intended for his tomb chapel there. Tragically, his son and heir, Orazio, succumbed to the plague shortly afterward. Titian apparently left no formal will, leading to disputes over his considerable estate.

Titian's death marked the end of an era, but his influence was just beginning its long trajectory. He became a cornerstone of the European painting tradition. His use of color and light profoundly impacted Baroque masters like Peter Paul Rubens (who copied many of his works), Anthony van Dyck, and Diego Velázquez. Rembrandt van Rijn studied and collected Titian's works, learning from his portraiture and composition.

Later artists continued to draw inspiration from him: Nicolas Poussin adapted his mythological compositions, Antoine Watteau echoed his fête champêtre scenes, Eugène Delacroix admired his color and passion, and Francisco Goya learned from his portraits and expressive late style. From El Greco, who absorbed Venetian color before developing his unique Spanish style, to Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who revived Venetian grandeur in the 18th century, Titian's legacy resonated through the centuries.

Conclusion: The Soul of Venice

Tiziano Vecellio remains a titan of art history. His unparalleled mastery of color, his revolutionary compositions, his profound psychological insight, and his sheer productivity across a long life secured his place as the dominant force in 16th-century Venetian painting and a key figure of the High Renaissance. From dramatic religious altarpieces and insightful portraits to sensual mythological scenes, his work explored the full range of human experience with unmatched richness and emotional depth. Titian not only defined the Venetian school but also fundamentally shaped the future direction of oil painting, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire and captivate audiences worldwide. He truly captured the vibrant, worldly, and color-drenched soul of Venice itself.