Jacopo Palma, known as Palma il Giovane (the Younger) to distinguish him from his great-uncle Palma Vecchio (the Elder), stands as one of the most significant and undeniably prolific painters in Venice during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Born Jacopo Negretti in Venice around 1548 or 1550, he lived through a transformative period in the city's artistic history, ultimately inheriting the mantle of the great Venetian masters who preceded him. His long career, stretching until his death in 1628, bridged the gap between the High Renaissance splendors of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, and the emerging Baroque era, leaving an indelible mark on the visual landscape of Venice.

Palma il Giovane's life and work are characterized by immense productivity, a skillful synthesis of prevailing artistic trends, and a deep engagement with the religious and civic demands of his time. He navigated the complex artistic currents, absorbing lessons from the giants of Venetian color and light, while also integrating the dramatic dynamism and compositional complexity favored by Central Italian Mannerism. His legacy is vast, found not only in museums worldwide but also ubiquitously within the churches, palaces, and scuole (confraternities) of Venice itself.

Early Life, Roman Sojourn, and Formative Influences

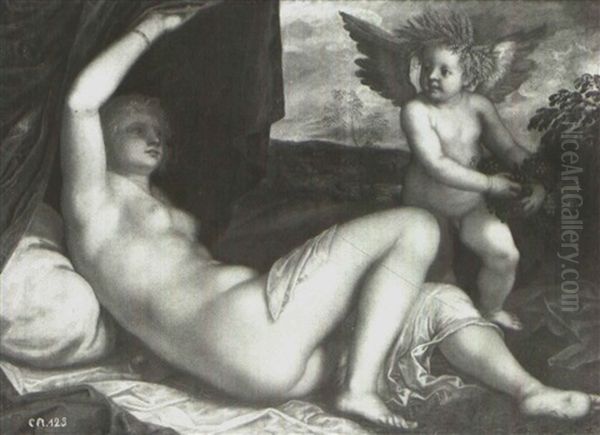

Born into an artistic family, Jacopo was the son of Antonio Negretti, a painter, and Giulia Brunello, who was the niece of Palma Vecchio (Jacopo d'Antonio Negretti, c. 1480–1528). This lineage placed him firmly within Venice's artistic milieu from birth. His great-uncle, Palma Vecchio, was a distinguished painter of the High Renaissance, known for his sensuous depictions of female figures and serene sacra conversazione scenes, establishing a notable artistic reputation that the younger Palma would eventually build upon.

Recognizing his burgeoning talent, Guidobaldo II della Rovere, the Duke of Urbino, became an early and crucial patron. Around 1567, the Duke took the young Palma to Urbino and subsequently sponsored his studies in Rome for several years, likely until the early 1570s. This period was profoundly formative. Rome exposed him to the monumental works of the High Renaissance masters, particularly the powerful forms and dramatic narratives of Michelangelo, whose Sistine Chapel frescoes left a lasting impression. He also studied the works of Raphael and absorbed the principles of Central Italian design and draftsmanship.

Furthermore, his time in Rome allowed him to study antique sculpture and the works of other contemporary Mannerist painters active in the city. This immersion in a different artistic environment, one that emphasized line, complex composition, and anatomical precision alongside emotional intensity, provided a crucial counterpoint to the colorito-focused tradition of his native Venice. He diligently copied works by Titian and others for the Duke, honing his skills and developing his understanding of different artistic approaches. Some accounts also mention his engagement in charitable and religious activities during his Roman stay, reflecting the pious atmosphere of the Counter-Reformation era.

Return to Venice and the Mantle of Titian

Palma il Giovane returned to Venice around 1573-1574, equipped with a sophisticated understanding of both Venetian and Roman artistic traditions. His timing was significant. Venice's established artistic giants were aging. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), the undisputed master, was nearing the end of his exceptionally long life. Jacopo Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) and Paolo Veronese (Paolo Caliari) were at the height of their powers but represented distinct stylistic paths.

A pivotal moment occurred shortly after his return. Tradition holds that Palma spent some time in Titian's workshop. Whether a formal apprenticeship or a looser association, the connection culminated in a significant act of artistic succession. When Titian died of the plague in 1576, he left his final, deeply personal Pietà unfinished in his studio. It was Palma il Giovane who was entrusted with completing this powerful work, destined for Titian's own burial chapel in the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Palma added the flying angel bearing a torch and inscribed the painting, acknowledging his role in finishing the master's final statement. This act symbolically positioned him as an heir to Titian's legacy. The completed Pietà now resides in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice.

Dominance in Late Cinquecento Venice

The deaths of Titian in 1576 and Veronese in 1588, followed by Tintoretto in 1594, created a vacuum in the Venetian art scene. Palma il Giovane, alongside Tintoretto's son Domenico Tintoretto and the Bassano family workshop (led by Jacopo Bassano and continued by his sons Francesco Bassano the Younger and Leandro Bassano), stepped into this void. However, due to his skill, adaptability, and sheer productivity, Palma il Giovane arguably became the most dominant painter in Venice for several decades.

A catastrophic fire in the Doge's Palace in 1577 destroyed major works by artists like Gentile da Fabriano, Pisanello, Gentile Bellini, Giovanni Bellini, Vittore Carpaccio, Titian, and Veronese. This disaster, while tragic, created immense opportunities for the current generation of artists. Palma il Giovane received numerous prestigious commissions for the redecoration effort, working alongside Veronese, Tintoretto, Francesco Bassano, and others to replace the lost masterpieces with vast canvases depicting Venetian history, allegories, and religious scenes. His contributions can still be seen in halls like the Sala del Maggior Consiglio and the Sala dello Scrutinio, cementing his status as a painter central to the Republic's official image.

He established a large and highly efficient workshop to handle the immense demand for his work. Commissions poured in from churches, confraternities (scuole), and private patrons throughout Venice and the Veneto region. His ability to work quickly and effectively on a large scale, adapting his style to suit the subject matter and the patron's requirements, made him the go-to artist for major decorative cycles and altarpieces.

Artistic Style: Synthesis and Energy

Palma il Giovane's style is a fascinating synthesis of the major artistic currents of his time. He masterfully blended the rich color, dramatic light, and painterly brushwork characteristic of the Venetian school (inherited from Titian and Tintoretto) with the dynamic compositions, elongated figures, complex poses, and emotional intensity of Central Italian Mannerism (absorbed during his time in Rome and reinforced by Tintoretto's example).

His works often feature crowded compositions filled with energetic figures in twisting, sometimes exaggerated poses. He employed strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), leaning towards tenebrism in some later works, to heighten the drama and emotional impact of his narratives. His brushwork could be rapid and vigorous, particularly in large-scale narrative canvases, conveying a sense of immediacy and movement reminiscent of Tintoretto. However, he could also adopt a more polished finish when required, especially in smaller devotional works or portraits.

His color palette, while rooted in Venetian tradition, sometimes incorporated the sharper, more artificial hues associated with Mannerism. He excelled at depicting rich textiles, gleaming armor, and atmospheric effects. While perhaps not reaching the sublime heights of Titian's color or Tintoretto's spiritual intensity, Palma's style was highly effective, adaptable, and perfectly suited to the narrative and devotional needs of the Counter-Reformation era, which demanded clear, emotionally engaging religious art. His subjects ranged from large-scale historical and allegorical cycles for the state to countless altarpieces, mythological scenes, and portraits.

Major Commissions and Representative Works

Palma il Giovane's output was staggering, and much of it remains in situ in Venice, offering a unique opportunity to see his work in its original context. Beyond his crucial contributions to the Doge's Palace, several other locations showcase his extensive activity:

Oratorio dei Crociferi: This small oratory, near the Gesuiti church, contains a significant cycle of paintings executed by Palma between 1583 and 1591, depicting events related to the history of the Crociferi order and the building's patrons. It provides an immersive experience of his narrative style.

Venetian Churches: Palma's altarpieces and lateral canvases adorn numerous churches across Venice. Examples include San Giacomo dall'Orio (sacristy paintings), San Zulian (St. Julian), San Nicolò dei Mendicoli, Santo Stefano, San Geremia, the Frari, and San Giovanni Elemosinario, among many others. These works cover a wide range of religious subjects, from dramatic martyrdoms to serene depictions of saints.

Scuole Grandi: He also received commissions from Venice's powerful lay confraternities, such as the Scuola Grande di San Marco.

Drawings and Prints: Palma was also a prolific draftsman. Thousands of his drawings survive, showcasing his working process and compositional ideas. These drawings, often characterized by rapid pen strokes and fluid washes, are highly valued. He also produced etchings. The Museo Correr in Venice holds a significant collection of his graphic work.

Portraits: While less famous for portraiture than for religious and historical painting, he did produce portraits, including a notable self-portrait housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera (Milan) and another mentioned in the Querini Stampalia Museum (Venice).

The Pietà finished for Titian remains a key work, symbolizing his connection to the High Renaissance masters. His cycles in the Doge's Palace represent his contribution to the official art of the Venetian Republic. The Oratorio dei Crociferi cycle offers perhaps the most complete view of his narrative abilities in a single, preserved environment.

Collaborations, Contemporaries, and Workshop

Palma il Giovane operated within a vibrant artistic community. His collaboration with Paolo Veronese on the Doge's Palace decorations is well-documented, demonstrating his ability to work alongside other leading masters. He was undoubtedly influenced by, and competed with, Jacopo Tintoretto, whose dramatic style left a clear mark on Palma's own work.

His workshop was crucial to his immense output. Like Veronese and Tintoretto before him, Palma employed numerous assistants to help execute large commissions, transfer designs to canvas, and paint less critical areas. This collaborative workshop model allowed him to maintain a high volume of production throughout his long career. While the quality could sometimes vary depending on the degree of workshop participation, Palma's guiding hand is usually evident.

He was a contemporary of the Bassano family painters, whose rustic genre scenes and religious works offered a different flavor of Venetian art. He also worked during the time of the prominent sculptor Alessandro Vittoria, who similarly contributed significantly to the decoration of Venetian churches and palaces. While influenced by earlier figures like Paris Bordone (a pupil of Titian), Palma's primary artistic dialogue was with the towering figures of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, whose legacy he consciously adapted and perpetuated.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Palma il Giovane remained active and highly sought after well into his later years, continuing to receive commissions until shortly before his death. He passed away in Venice on October 14, 1628, at the age of approximately 80. He was buried in the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, a prestigious resting place shared by many Doges and near the tombs of his great-uncle Palma Vecchio and, poignantly, Titian himself.

His legacy is complex. While sometimes criticized for prioritizing quantity over consistent quality or for lacking the profound originality of Titian or Tintoretto, Palma il Giovane played an indispensable role in Venetian art history. He was the dominant figure who carried the Venetian painting tradition forward after the passing of its greatest exponents. His ability to synthesize diverse influences, manage a large workshop, and fulfill the vast artistic needs of the city and its territories was remarkable.

His influence extended to the next generation of Venetian painters, though the city's artistic prominence began a slow decline after his death. His energetic style and narrative clarity provided a model for many artists working in Venice and the Veneto in the early 17th century. He remains the last major figure of Venice's extended Renaissance painting tradition, a prolific and skilled artist whose work defines the visual culture of the city during his era.

Collections and Surviving Works

Today, Palma il Giovane's works are found in major museums across the globe, but the greatest concentration remains in Venice.

Venice: Gallerie dell'Accademia (including the Pietà finished for Titian, and numerous other works), Doge's Palace (extensive cycles), Museo Correr (drawings, prints), Querini Stampalia Foundation, Oratorio dei Crociferi, and countless churches throughout the city.

Italy: Pinacoteca di Brera (Milan), Uffizi Gallery (Florence), Borghese Gallery (Rome), and numerous regional museums.

International Museums: Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna), Musée du Louvre (Paris), Museo del Prado (Madrid), National Gallery (London), Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Art Institute of Chicago, National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.), and many others hold significant paintings and drawings by Palma il Giovane.

His vast surviving oeuvre allows for a deep appreciation of his stylistic range, his narrative power, and his central role in the artistic life of late Renaissance and early Baroque Venice. He stands as a testament to the enduring vitality of the Venetian school, a bridge between giants, and a master in his own right.