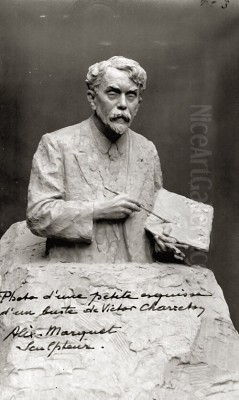

Victor Charreton stands as a significant figure in French Post-Impressionist painting, celebrated for his evocative landscapes and vibrant still lifes. Born in 1864 and passing away in 1936, his life spanned a period of immense artistic change in France. Though initially trained in law, Charreton ultimately dedicated his life to art, becoming a master of color and light, particularly renowned for his depictions of the Auvergne region and his sensitive rendering of seasonal effects, especially snow. His work, while rooted in the observational principles of Impressionism, developed a distinct personal style characterized by rich palettes, textured surfaces, and a profound connection to the natural world.

Early Life and the Path to Art

Victor Henri Charreton was born on March 2, 1864, in Bourgoin (now Bourgoin-Jallieu), a town in the Isère department of southeastern France. His early life suggested a different trajectory. Following a conventional path for a young man of his standing, he pursued legal studies, reportedly in Grenoble, and subsequently established a legal practice in Paris. For a time, he balanced the demands of a law career with his burgeoning passion for painting, a duality not uncommon in an era where art was often seen as a respectable pastime rather than a viable profession for those from certain backgrounds.

However, the pull of art proved irresistible. The precise moment or reason for his definitive shift remains personal, but by the turn of the century, Charreton had made the pivotal decision to abandon his legal career and devote himself entirely to painting. This was a courageous step, exchanging the security of law for the uncertainties of an artist's life. This transition marked the true beginning of his journey as a professional painter, allowing him to fully immerse himself in the study and practice of his chosen craft in the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris.

Artistic Formation and Impressionist Echoes

Upon committing to art full-time around 1902, Charreton sought formal and informal training in Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He associated with and learned from established artists, absorbing the influences that permeated the city's studios and galleries. Among his early mentors or significant influences were Ernest Victor Hareux (often cited as Hilaireux or Halereux) and Louis Aimé Japy (sometimes noted as Émile-Jean Lavedan in initial sources, but Japy is the more recognized landscape painter he associated with). These figures, landscape painters themselves, likely provided Charreton with foundational techniques and perspectives on capturing the nuances of nature.

The dominant artistic force of the preceding decades, Impressionism, inevitably left its mark on Charreton. He embraced key tenets of the movement: the importance of painting outdoors (en plein air) to directly capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, a brighter palette compared to academic tradition, and a focus on everyday landscapes rather than historical or mythological scenes. The works of masters like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, who had revolutionized the depiction of light and color, provided a powerful precedent. Charreton absorbed these lessons, particularly their dedication to observing and translating the visual sensations of nature onto canvas.

However, Charreton was not merely an Impressionist follower. He belonged to the subsequent generation often termed Post-Impressionist, artists who built upon Impressionism but sought more structure, personal expression, or symbolic meaning. While retaining the Impressionist emphasis on light and color, Charreton's work often exhibits a more solid sense of form and composition, and a more subjective, sometimes intensified, use of color compared to the purely optical approach of earlier Impressionists like Monet. His connection was more aligned with the ongoing exploration of landscape painting that continued to evolve after Impressionism's peak.

The Development of a Personal Style: Light, Color, and Season

Victor Charreton’s artistic identity is inextricably linked to his profound sensitivity to light and color, and his fascination with the changing seasons. He became a painter of atmosphere, adept at capturing the specific quality of light at different times of day and under various weather conditions. His landscapes are not just topographical records; they are studies in luminosity, exploring how sunlight filters through leaves, reflects off snow, or creates long shadows in the late afternoon.

His palette was distinctive, often characterized by rich, jewel-like tones. While capable of rendering the bright sunshine of Provence or the clear air of the mountains, he showed a particular affinity for nuanced and sometimes unexpected color combinations. He was noted for his use of mauves, violets, and deep blues, especially in his winter scenes and twilight landscapes. These choices went beyond mere observation, imbuing his work with a poetic and sometimes melancholic quality. His application of paint was often textured, using impasto and varied brushstrokes to convey the substance of objects and the vibrancy of light itself.

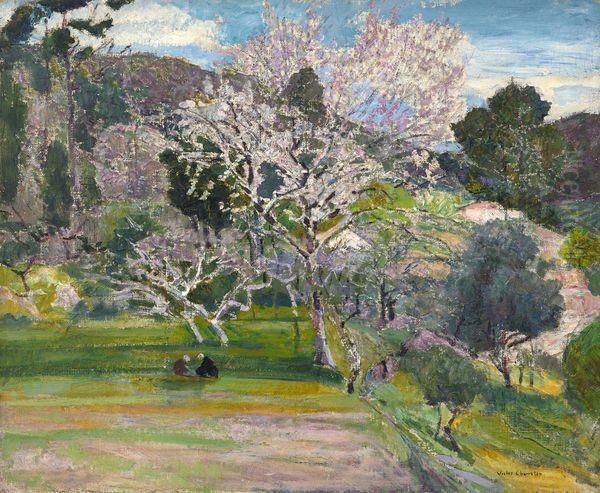

Charreton dedicated much of his career to exploring the cyclical beauty of the seasons. Spring landscapes feature blossoming trees rendered with delicate touches of color. Summer scenes pulse with the warmth and intensity of the sun. Autumn is depicted through a rich tapestry of reds, oranges, and golds. However, it was perhaps his winter landscapes, particularly his snow scenes, that earned him special recognition. He masterfully captured the subtle chromatic variations in snow – the blues and purples in the shadows, the pinks and yellows reflecting the low winter sun – avoiding pure white and revealing the complex interplay of light on a seemingly monochromatic surface.

Travels and Expanding Horizons

Like many artists of his time, Charreton understood the value of travel for expanding his visual repertoire and finding fresh inspiration. While deeply connected to certain regions of France, particularly his native Dauphiné and later the Auvergne, he journeyed beyond French borders. His travels took him to various European countries and across the Mediterranean.

Sources confirm visits to Algeria, Spain, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Each location offered unique landscapes, light conditions, and cultural atmospheres that enriched his artistic vision. In North Africa, he would have encountered the intense light and vibrant colors that had fascinated Orientalist painters and artists like Eugène Delacroix and later Henri Matisse. In Spain, the dramatic landscapes and strong contrasts likely appealed to his sense of color and form. The softer light and different atmospheric conditions of the Low Countries and Britain would have presented new challenges and opportunities for capturing nuanced effects.

These journeys provided Charreton with a broader range of subjects and prevented his art from becoming solely regional. While he remained most famous for his French landscapes, the experiences gathered abroad undoubtedly informed his technique and his understanding of how light and environment interact, adding depth and variety to his oeuvre. The sketches and studies made during these trips often served as source material for larger compositions completed back in his studio.

Key Themes: Auvergne, Snow, and Still Life

While Charreton painted various locations, certain themes recur throughout his work, forming the core of his artistic identity.

The Landscapes of Auvergne: Charreton developed a deep and lasting connection with the Auvergne region in central France, particularly around the village of Murol. The rugged volcanic landscape, rolling hills, picturesque villages, and dramatic weather patterns provided endless inspiration. He captured the ancient volcanoes (Puys), the winding rivers like the Couze Chambon, and the distinctive architecture of the region. His Auvergne paintings convey a sense of timelessness and a deep affection for the rural French countryside. This area became so central to his work that he later co-founded an art school there.

Mastery of Snow Scenes: As mentioned earlier, Charreton excelled in depicting winter landscapes blanketed in snow. These were not bleak or desolate scenes but opportunities to explore the subtle beauty and complex colors of winter light. He captured the muffled silence of a snow-covered village, the crisp air of a frosty morning, and the way snow transforms familiar shapes. His ability to render the texture of snow – powdery, melting, or crusted – and its interaction with light set his winter scenes apart. These works are among his most sought-after and demonstrate his technical skill and observational acuity, rivaling those of Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro who also famously tackled the subject.

The Intimacy of Still Life: Alongside his extensive landscape work, Charreton was a skilled painter of still lifes, particularly floral compositions. These works allowed him to explore color harmonies and textures on a more intimate scale. His flower paintings are characterized by their vibrant colors, sensitive rendering of petals and leaves, and often feature simple, rustic arrangements that feel natural rather than overly formal. He applied the same sensitivity to light and color seen in his landscapes to these interior subjects, capturing the way light falls across a vase or illuminates the delicate structure of a bloom. Artists like Henri Fantin-Latour had established a strong tradition of floral painting in France, and Charreton contributed his own distinct voice to this genre.

Technical Innovation: The Flocked Canvas

Beyond his stylistic contributions, Victor Charreton was also interested in the technical aspects of painting and art conservation. In his later years, he reportedly devoted time to researching methods for preserving artworks. More notably, he is credited with inventing or pioneering a specific painting technique involving a specially prepared canvas.

This technique utilized a type of canvas, possibly cotton or a similar fabric, which had a fine, velvety texture, sometimes described as "flocked." The purpose of this textured surface was likely twofold. Firstly, it could affect the way paint adhered and sat on the support, potentially allowing for different textural effects in the final painting. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the slightly raised, fibrous surface would interact with light differently than a standard smooth canvas. It might absorb light in certain ways or create a subtle diffusion, contributing to the overall luminosity or atmospheric quality of the finished work.

This interest in the physical materials and techniques of painting demonstrates Charreton's commitment to his craft on multiple levels. It suggests an artist who was not only concerned with visual representation but also with the fundamental means by which those representations were achieved and preserved. While perhaps not widely adopted, this technical exploration adds another dimension to his profile as a thoughtful and dedicated painter.

The Salon d'Automne and Official Recognition

Charreton's career gained significant momentum through his participation in the Parisian Salon system, particularly the more progressive Salon d'Automne (Autumn Salon). In 1903, he played a role in the founding or early organization of this important exhibition venue, alongside prominent artists like the Post-Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard, as well as figures like Henri Matisse and Albert Marquet who would soon be associated with Fauvism.

The Salon d'Automne was established as a reaction against the conservatism of the official Salon des Artistes Français. It aimed to provide a platform for newer, more experimental art forms and quickly became a major showcase for emerging talents and movements. Fauvism famously caused a scandal there in 1905. Charreton's involvement from the early stages indicates his alignment with the more forward-looking currents in French art, even if his own style remained relatively grounded in observation. Exhibiting regularly at the Salon d'Automne and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts brought his work to wider public and critical attention.

His growing reputation was solidified by official recognition. In 1914, Victor Charreton was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), one of France's highest civilian decorations, for his contributions to the arts. This prestigious award cemented his status as a respected figure within the French art establishment.

The Murols School: Fostering Landscape Painting

Charreton's deep connection to the Auvergne region led him to co-found an art school in Murol, known as the École de Murol (Murols School) or sometimes the École des Peintres de Murol. He established this initiative alongside fellow artist Léon Boudal. The school likely functioned primarily during the summer months, attracting artists drawn to the scenic beauty of the region that Charreton himself had so extensively painted.

The purpose of the Murols School was likely to promote landscape painting en plein air, carrying forward the traditions of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in a direct, immersive way. It provided a gathering place for artists to work, learn, and exchange ideas, focusing on the specific motifs and light conditions of the Auvergne. While perhaps not achieving the international fame of earlier artist colonies like Barbizon or Pont-Aven, the Murols School played a significant role in the regional art scene and helped to perpetuate a style of landscape painting deeply rooted in the observation of nature. It stands as a testament to Charreton's commitment not only to his own art but also to fostering artistic community and education.

Charreton and His Contemporaries

Victor Charreton's career unfolded during a dynamic period in French art, placing him amidst a constellation of influential figures. His relationships with contemporaries ranged from mentorship and collaboration to parallel development within shared artistic movements.

His early training connected him with Ernest Victor Hareux and Louis Aimé Japy, establishing his roots in the landscape tradition. His involvement in the Salon d'Automne brought him into contact with co-founders like Pierre Bonnard and exhibitors such as Henri Matisse, André Derain, Georges Rouault, and Albert Marquet. While stylistically distinct from the burgeoning Fauvist movement these latter artists represented, their shared exhibition space highlights the diverse artistic dialogues occurring in Paris at the time.

Charreton's work inevitably invites comparison with the great Impressionists who preceded him, particularly Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, whose approaches to light and landscape profoundly shaped the artistic environment Charreton entered. He shared their dedication to plein air painting and capturing atmospheric effects.

As a Post-Impressionist, his work can be situated alongside others who moved beyond strict Impressionism, such as Paul Cézanne, who sought underlying structure; Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, who emphasized subjective color and emotion; and Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who developed Pointillism. While Charreton did not adopt these specific radical departures, his intensified color and structured compositions reflect the broader Post-Impressionist exploration of form and expression.

His focus on specific genres also connects him to others. His floral still lifes resonate with the tradition of Henri Fantin-Latour. His snow scenes continue a theme explored by Monet and Pissarro, as well as Gustave Courbet before them. His collaboration with Léon Boudal in founding the Murols School demonstrates a direct working relationship aimed at shared artistic goals. He navigated this complex artistic landscape, developing his own voice while engaging with the dominant trends and figures of his time. He was not an isolated figure but an active participant in the rich tapestry of early 20th-century French art.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Victor Charreton continued to paint with dedication, primarily focusing on the landscapes and themes that had defined his career. He divided his time between Paris, his beloved Auvergne, and potentially other favored locations. His reputation as a master of landscape and snow scenes was well-established, and he remained active in exhibiting his work.

A significant part of his legacy was secured through his own efforts and the appreciation of his home region. He was instrumental in the creation of the Musée Victor Charreton, located in his birthplace of Bourgoin-Jallieu. This museum, established during his lifetime or shortly thereafter, houses a significant collection of his works, providing a dedicated space for the study and appreciation of his art. It serves as the primary center for understanding the breadth and depth of his oeuvre.

Victor Charreton passed away on November 26, 1936, in Clermont-Ferrand, the main city of the Auvergne region he loved so dearly. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be admired for its technical skill, sensitivity to nature, and evocative use of color and light. His legacy lies in his contribution to the French landscape tradition, his mastery of specific themes like snow scenes, his role in founding the Salon d'Automne and the Murols School, and the enduring appeal of his depictions of the French countryside.

Market Reception and Museum Collections

Victor Charreton's work has maintained a consistent presence in the art market, particularly within France, though perhaps without reaching the stratospheric prices of some of his Impressionist predecessors or later modern masters. His paintings appear regularly at auction, with landscapes, especially snow scenes and views of Auvergne or Provence, generally being the most sought after.

Auction results vary depending on the size, subject matter, period, and condition of the work. As noted in the initial information, an oil painting like Arbre en fleur (Flowering Tree) might be estimated in the range of several thousand euros, indicating a solid market appreciation for good examples of his work. While not typically commanding the multi-million dollar figures associated with artists like Monet or Van Gogh, or contemporary giants like Gerhard Richter, Charreton's paintings are respected collector's items, valued for their intrinsic artistic merit and historical context.

His work is represented in the collections of several important public institutions, confirming his place in art history. Notably, his paintings can be found in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the premier museum for French art of the period 1848-1914. His inclusion there places him firmly within the canon of significant French artists of his era. Works are also held in international collections, such as the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The most comprehensive collection, however, remains at the Musée Victor Charreton in Bourgoin-Jallieu, dedicated specifically to his life and art.

Conclusion: A Poet of the French Landscape

Victor Charreton carved a distinct niche for himself within the rich landscape of French Post-Impressionist art. Transitioning from law to a life dedicated to painting, he became a masterful interpreter of the natural world, particularly the landscapes of rural France. His work resonates with the Impressionist fascination for light and atmosphere but pushes towards a more personal and richly colored expression. He excelled in capturing the nuances of the seasons, earning particular acclaim for his luminous and colorful snow scenes.

Through his involvement with the Salon d'Automne, his co-founding of the Murols School, and his technical explorations, Charreton demonstrated a deep engagement with the artistic currents and practices of his time. While perhaps overshadowed in popular recognition by some of the more revolutionary figures of his era, his paintings possess an enduring appeal, celebrated for their sensitivity, technical assurance, and the palpable affection they convey for the landscapes he depicted. Victor Charreton remains a significant figure, a poet in paint who captured the light, color, and soul of the French countryside for generations to appreciate.