Introduction: A New Vision for Landscape

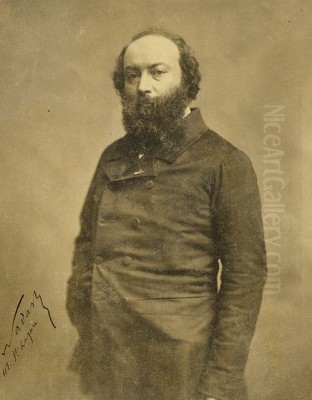

Pierre Étienne Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of French art, particularly renowned as a leading force behind the Barbizon School. A dedicated landscape painter, Rousseau challenged the prevailing artistic conventions of his time, championing a move towards Naturalism and direct observation of the environment. His profound connection with nature, especially the forests and rural scenes of France, fueled a body of work that not only captured the physical reality of the landscape but also conveyed its inherent mood and spirit. Though facing significant resistance from the official art establishment for much of his career, Rousseau's persistent dedication to his vision ultimately reshaped French landscape painting and laid crucial groundwork for the Impressionist movement that followed.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Paris in 1812, Théodore Rousseau's path towards art was perhaps subtly influenced by his family background. His father worked as a tailor, representing a connection to craftsmanship, while his mother hailed from a family with artistic inclinations. This blend may have nurtured his nascent creative sensibilities. From a young age, Rousseau displayed a deep fascination with the countryside and the natural world, an interest that diverged from the urban environment of his birth.

A formative experience occurred during his youth when he spent time working at a sawmill in the rugged Jura Mountains near the Swiss border. This period immersed him directly in the forest environment, fostering an intimate understanding and enduring love for woodland scenery. The textures of bark, the play of light through leaves, the raw power and tranquility of the woods – these elements became deeply ingrained in his artistic consciousness and would remain central motifs throughout his career. This early, unmediated contact with nature proved more influential than any formal academic training he would later receive.

Formative Training and Influences

Rousseau's initial artistic steps involved studying the works of established masters. He particularly admired the classical landscape traditions, looking towards figures like the 17th-century French painter Claude Lorrain, known for his idealized, light-filled compositions. He also absorbed lessons from the Dutch Golden Age landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael, who excelled in capturing the specific character and atmospheric conditions of their native scenery with remarkable realism.

Seeking more formal instruction, Rousseau briefly engaged with the academic system, receiving some training, possibly connected to the circle around painters like Guillaume Guillon-Lethière or working alongside historical landscape painters such as Jacques Charles Joseph Caresme. However, the rigid Neoclassical doctrines prevalent in the French Academy and its official exhibition venue, the Salon, proved incompatible with Rousseau's burgeoning desire for a more direct, personal, and truthful depiction of nature. He increasingly sought inspiration not in historical or mythological narratives imposed upon the landscape, but in the landscape itself.

The influence of contemporary English landscape painters, particularly John Constable and Richard Parkes Bonington, was also significant. Their work, which emphasized capturing the fleeting effects of light and weather through direct observation and often employed looser brushwork, resonated with Rousseau's own inclinations. Constable's dedication to painting the familiar countryside of Suffolk, imbuing it with freshness and atmospheric truth, offered a powerful alternative to the idealized Italianate scenes favored by the French Academy.

The Salon Rejections and "Le Grand Refusé"

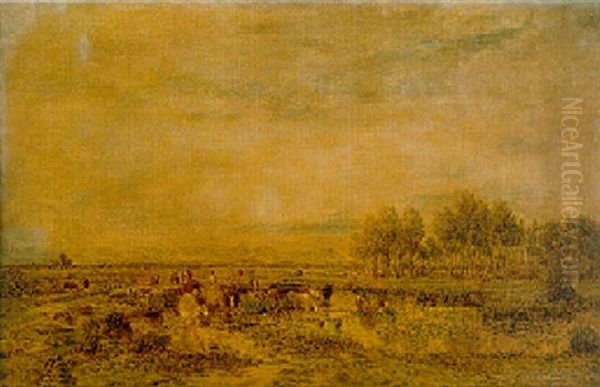

Rousseau's commitment to his independent vision quickly brought him into conflict with the conservative jury of the Paris Salon. Beginning in the mid-1830s, his submissions were frequently rejected. A notable example was his ambitious painting, The Descent of the Cattle in the High Plateaux of the Jura (La Descente des Vaches des Hautes Plateaux du Jura), likely completed around 1834-35 and rejected by the Salon of 1836. This work, depicting a scene rooted in his youthful experiences, showcased his early commitment to realism and specific regional landscapes, diverging sharply from the Salon's expectations.

These repeated rejections, which continued for over a decade, earned Rousseau the unfortunate nickname "Le Grand Refusé" (The Great Refused One). This period of official exclusion was undoubtedly difficult, limiting his public exposure and potential patronage. However, it did not deter him. Instead, it arguably strengthened his resolve and pushed him further towards developing his unique style outside the confines of academic approval. He spent these years traveling extensively throughout France – visiting Auvergne, Normandy, and other regions – sketching and painting directly from nature, honing his observational skills and deepening his connection to the French landscape.

Barbizon: A Haven for Naturalism

Frustrated by the Salon system but undeterred in his artistic pursuits, Rousseau sought refuge and inspiration away from Paris. Around the mid-1830s and increasingly through the 1840s, he began spending significant time in the village of Barbizon, situated on the edge of the vast Forest of Fontainebleau. This ancient forest, with its dramatic rock formations, towering oaks, and varied terrain, offered endless subject matter perfectly suited to his artistic temperament.

Barbizon soon became a gathering place for a like-minded group of artists who shared Rousseau's dissatisfaction with academic constraints and his passion for painting nature realistically and directly. This informal collective, which became known as the Barbizon School, included notable figures such as Jean-François Millet, famous for his dignified portrayals of peasant life; Charles-François Daubigny, known for his river scenes often painted from his studio boat; Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña, who specialized in dramatic forest interiors and mythological scenes set in nature; and Jules Dupré, who became one of Rousseau's closest friends and collaborators.

While not a formally organized school with a strict manifesto, the Barbizon painters were united by their commitment to plein air (outdoor) sketching and painting, their focus on capturing the specific light and atmosphere of a location, and their belief in the inherent dignity and beauty of the unadorned landscape. Rousseau, with his early dedication to these principles and his profound interpretations of the Forest of Fontainebleau, naturally emerged as a central figure and leader within this group.

Rousseau's Artistic Style: Capturing Nature's Soul

Théodore Rousseau's style is characterized by its profound naturalism, a deep reverence for the subject matter, and a meticulous yet expressive technique. He sought to capture not just the appearance of a landscape, but its underlying structure, its mood, and the specific effects of light and atmosphere at a particular moment. His work bridges the gap between the lingering Romantic sensibility for nature's power and the burgeoning Realist impulse towards objective representation.

His observation was intense and detailed. He studied the intricate branching of trees, the textures of rocks and soil, the subtle shifts in color under changing skies. This meticulousness, however, was combined with an increasingly bold and often textured application of paint. His brushwork could range from fine, delicate strokes rendering specific details to broader, more vigorous applications capturing mass and energy. This sometimes resulted in surfaces that appeared "unfinished" or rough to academic eyes but were crucial for conveying the vitality and immediacy of the scene.

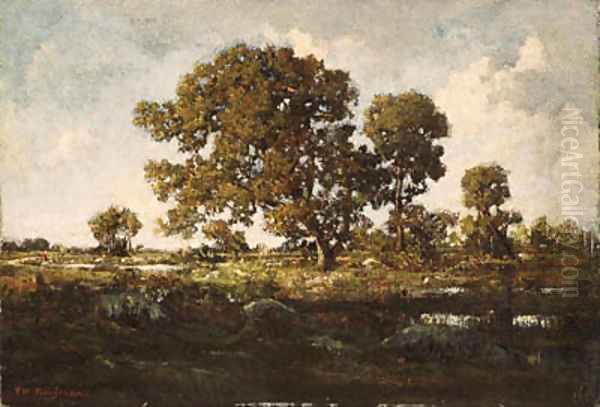

Light was a primary concern for Rousseau. He was fascinated by the way sunlight filtered through leaves, reflected off water, or illuminated the sky at dawn or dusk. Many of his most famous works explore these effects, particularly the dramatic light of sunrise and sunset. He employed a rich, often somber color palette, dominated by earthy greens, browns, and ochres, punctuated by the vibrant hues of the sky. His compositions often emphasize the grandeur and permanence of nature, sometimes featuring solitary, majestic trees or expansive views that dwarf human presence.

Key Works: Visions of Fontainebleau and Beyond

Several paintings stand out as representative of Rousseau's artistic achievement and stylistic evolution. Sunset from the Edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau (c. 1848-1850, Louvre Museum) is perhaps his most iconic work and a quintessential Barbizon painting. It depicts a dramatic, fiery sunset over the plains bordering the forest, with gnarled oak trees silhouetted against the glowing sky. The painting masterfully combines detailed observation of the trees with a powerful evocation of atmosphere and mood, capturing the sublime beauty of nature at the day's end.

The Chestnut Avenue (c. 1837-1840), showcases his ability to render the intricate structure of trees and the play of dappled light within a woodland setting. The careful depiction of the massive, ancient trees conveys a sense of permanence and history embedded within the natural world. This work reflects his deep study of tree forms, which became a hallmark of his art.

His earlier, rejected work, The Descent of the Cattle, while perhaps less stylistically mature than his later masterpieces, is significant for its early commitment to depicting specific regional landscapes and rural life, themes central to the Barbizon ethos. It demonstrates his early break from idealized scenery towards a more grounded representation of the French countryside.

Another powerful example is Mont Blanc seen from La Faucille, Storm Effect (c. 1834). This painting, while still rooted in observation, incorporates a more Romantic sensibility, emphasizing the sublime power of nature through the depiction of a dramatic mountain landscape under stormy skies. It highlights the blend of influences in his early work and his ability to convey nature's more tumultuous aspects. These works, among many others held in collections like the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, demonstrate the range and depth of his engagement with landscape.

Relationships and Artistic Circle

Rousseau's life in Barbizon fostered close relationships with fellow artists. His friendship with Jules Dupré was particularly significant. They met in the 1830s and, for a time, were almost inseparable, traveling together in the 1840s to study landscapes in regions like the Landes. Dupré deeply admired Rousseau's work and was instrumental in promoting it, particularly to German audiences. Their artistic dialogue undoubtedly influenced both painters, though differences eventually led to a cooling of their intense friendship.

He shared the Barbizon environment with Jean-François Millet, whose focus on peasant figures complemented Rousseau's dedication to the landscape itself. While their primary subjects differed, they shared a profound respect for rural life and the natural world. Interactions with Charles-François Daubigny and Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña were also part of the fabric of Barbizon life, contributing to the shared atmosphere of artistic exploration focused on nature.

Rousseau also maintained connections with other prominent figures in the art world. He had contact with the leading Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. He was acquainted with the influential landscape painter Camille Corot, another artist associated with Barbizon, though Corot maintained closer ties to the official Salon system. Rousseau benefited from the support of the critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger, who championed his work in articles from the 1840s onwards, recognizing him as a leading figure in modern landscape painting. Alfred Sensier, also a critic and biographer (notably of Millet), was another long-term friend and supporter. Through Maurice Sand, Rousseau also became acquainted with the celebrated writer George Sand.

Recognition, Later Life, and Advocacy

After more than a decade of being largely excluded from the Salon, the political changes following the Revolution of 1848 brought a more liberal attitude to the art establishment. Rousseau's fortunes began to change. At the Salon of 1849, the state purchased one of his works, and he was finally awarded a first-class medal. Further recognition followed, including another gold medal in 1852 and the Legion of Honour. In 1855, a special retrospective exhibition of his work was held as part of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, solidifying his reputation.

His growing stature was confirmed in 1857 when he was appointed as a member of the Salon jury – a remarkable turnaround for the former "Grand Refusé." Despite this official acceptance and the increasing demand for his paintings, which began to command high prices, Rousseau continued to live relatively modestly in Barbizon. He remained deeply committed to his art and to the place that had nurtured it.

Beyond his painting, Rousseau demonstrated a pioneering concern for environmental preservation. Witnessing the threats posed by logging to his beloved Forest of Fontainebleau, he actively campaigned for its protection. He was instrumental in the effort to establish protected 'artistic reserves' within the forest, marking one of the earliest examples of nature conservation efforts driven by artistic and aesthetic values. This advocacy reveals the depth of his connection to the natural world, extending beyond representation to active stewardship.

Legacy and Influence

Théodore Rousseau died in Barbizon in 1867, at the age of 55, following a period of illness, possibly paralysis. Although he achieved significant recognition during his later years, his full impact on the course of art history became even clearer posthumously. He is now universally acknowledged as a master of 19th-century French landscape painting and the driving force behind the Barbizon School.

His unwavering commitment to direct observation, his focus on capturing the specific character and atmosphere of the French landscape, and his innovative techniques profoundly influenced the next generation of artists. The Impressionists, including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, built upon the foundations laid by Rousseau and his Barbizon colleagues. They adopted the practice of plein air painting, explored the fleeting effects of light and color with even greater intensity, and shared a dedication to depicting contemporary landscapes and everyday scenes. Rousseau's textured brushwork and emphasis on capturing immediate sensory experience prefigured key aspects of Impressionist technique.

Rousseau's legacy lies in his successful elevation of landscape painting from a minor genre, often subservient to historical or mythological themes, to a major form of artistic expression in its own right. He demonstrated that the familiar forests, fields, and skies of France were worthy subjects for serious art, capable of conveying profound emotion and complex ideas. His deep, almost spiritual connection to nature resonated through his canvases, offering a powerful counterpoint to the increasing industrialization and urbanization of the 19th century.

Conclusion: The Enduring Forest

Théodore Rousseau's journey was one of artistic conviction and perseverance. Facing down years of official rejection, he remained true to his vision of a landscape art rooted in direct experience and emotional honesty. In the forests of Fontainebleau and the village of Barbizon, he found both his subject matter and a community that shared his ideals. As the leader of the Barbizon School, he spearheaded a movement that fundamentally changed the course of landscape painting, emphasizing naturalism, atmosphere, and the inherent beauty of the everyday environment. His meticulous observation, combined with his expressive power, created works that continue to resonate with viewers today, inviting contemplation of the enduring power and intricate beauty of the natural world. His influence extended far beyond his own lifetime, paving the way for Impressionism and securing his place as one of the most important landscape painters of the 19th century.