Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916) stands as a unique and compelling figure in the landscape of European art. A Danish painter celebrated primarily for his serene, atmospheric, and often enigmatic interior scenes, Hammershøi developed a distinctive style characterized by a muted palette, a profound sensitivity to light, and an exploration of quietude and introspection. Though relatively isolated from the mainstream avant-garde movements of his time, his work resonates with a timeless quality, earning him posthumous recognition as one of Scandinavia's most important artists and the evocative title, "the Vermeer of the North."

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Vilhelm Hammershøi was born in Copenhagen on May 15, 1864, into a prosperous merchant family. His parents, Christian and Frederikke Hammershøi (née Rentzmann), recognized and encouraged his artistic inclinations from a young age. He began receiving drawing lessons at the tender age of eight, initially studying under Niels Christian Kierkegaard (a cousin of the famous philosopher Søren Kierkegaard) and Holger Grønwall. This early training laid a solid foundation for his technical skills.

His formal art education continued at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, which he attended from 1879 to 1884. Here, he honed his craft, absorbing the academic traditions but already beginning to hint at a more personal and introspective vision. Following his time at the Academy, he sought further instruction, studying from 1883 to 1885 at the Independent Study School (Kunstnernes Frie Studieskoler), an alternative institution founded by artists dissatisfied with the Academy's conservatism. A key figure here was Peder Severin Krøyer, a leading light of the Skagen Painters, known for his vibrant depictions of Danish coastal life.

Emergence and Early Style

Hammershøi made his public debut in 1885 at the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition, the official annual showcase of the Royal Academy. He presented a striking portrait of his sister, Anna Hammershøi. This work, Portrait of a Young Girl (Anna Hammershøi), already displayed elements of his developing style: a controlled composition, a subtle psychological presence, and a somewhat restricted colour range. However, its departure from conventional portraiture norms led to its rejection for the Academy's Neuhausen Prize, an early sign of the art establishment's occasional difficulty in categorizing his unique approach.

Despite this initial setback, Hammershøi continued to develop his singular vision. His early works were sometimes criticized for their limited palette, often dominated by greys, whites, and blacks, which stood in contrast to the brighter colours favoured by many contemporaries, including the Impressionists or even the Skagen Painters like Michael Ancher and Anna Ancher, whose work celebrated natural light and communal life. Hammershøi, however, was charting a different course, one focused on nuance, mood, and the poetics of the understated. He briefly became associated, albeit informally, with the Skagen group in the 1890s, but his temperament and artistic concerns remained distinct.

The Signature Style: Interiors and Atmosphere

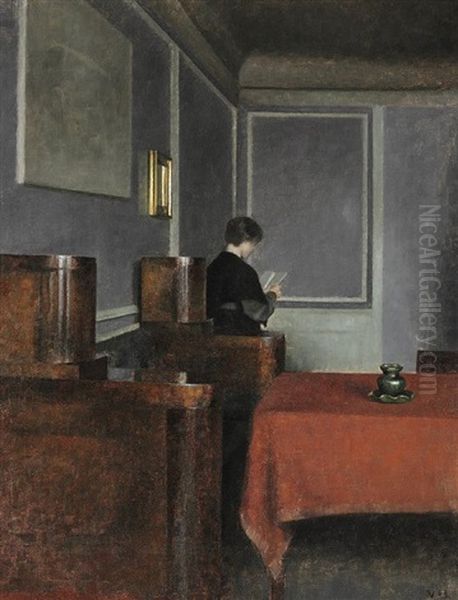

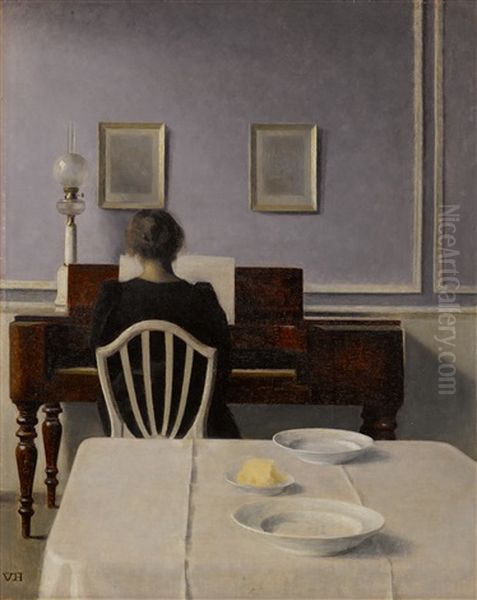

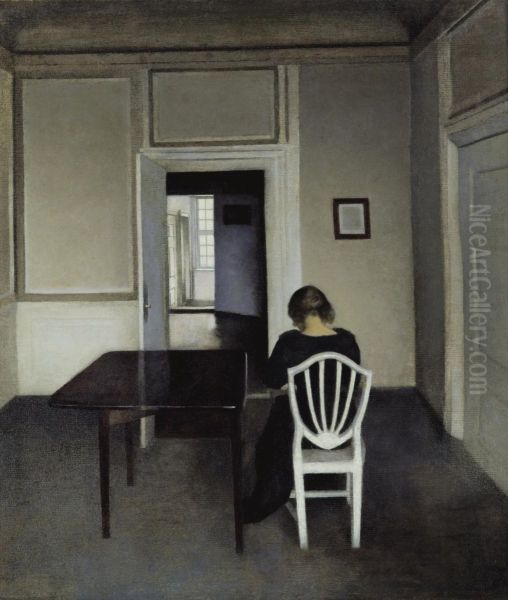

Hammershøi is best known for his interior scenes, which form the core of his oeuvre. These paintings typically depict sparsely furnished rooms, often within his own apartments, bathed in the cool, diffuse light of Northern Europe. His palette is famously restrained, dominated by shades of grey, white, black, brown, and muted blues and greens. This deliberate limitation of colour creates a powerful sense of harmony, stillness, and introspection. It forces the viewer to focus on the subtleties of tone, texture, and, most importantly, light.

Light is arguably the central protagonist in Hammershøi's interiors. It streams through windows, falls across bare wooden floors, illuminates dust motes in the air, and reflects off simple objects like doors, chairs, and picture frames. He masterfully captured the specific quality of Nordic light – its softness, its coolness, its ability to define form and create mood. The interplay of light and shadow is meticulously rendered, contributing to the paintings' quiet drama and spatial complexity. The atmosphere is often one of profound silence, contemplation, and sometimes a gentle melancholy.

This focus on light, domestic space, and quietude inevitably drew comparisons to the 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Vermeer. Like Vermeer, Hammershøi elevated the everyday interior to a subject of profound artistic meditation, using light and composition to imbue simple scenes with a sense of mystery and timelessness. However, Hammershøi's work possesses a distinctly modern sensibility, often tinged with a feeling of isolation or psychological distance absent in Vermeer's more populated scenes. His tonal harmonies also find parallels in the work of James McNeill Whistler, another contemporary artist deeply concerned with subtle colour relationships and atmospheric effects.

The Muse and the Home: Ida and Strandgade 30

A recurring figure in Hammershøi's interiors is his wife, Ida Ilsted (sister of the painter Peter Ilsted, another artist exploring quiet interiors). They married in 1891, and Ida became his primary model. However, she is rarely presented as a conventional portrait subject. More often, she is depicted from behind, absorbed in a simple domestic task like reading, sewing, or playing the piano, or simply standing gazing out of a window or into an adjacent room. Her face is often obscured or turned away, rendering her an anonymous, almost archetypal presence within the space.

This depiction contributes to the paintings' enigmatic quality. Ida becomes less an individual personality and more an integral part of the composition, a human element within the carefully structured geometry of the room, embodying the themes of solitude and contemplation that permeate his work. Her presence emphasizes the quiet intimacy of domestic life, yet her frequent averted gaze also suggests an inner world inaccessible to the viewer, adding a layer of psychological intrigue.

The apartments where Vilhelm and Ida lived served as the primary settings for his art. Most famously, their residence from 1898 to 1909 at Strandgade 30 in the Christianshavn district of Copenhagen became the backdrop for many of his most iconic works. The specific architectural features of this apartment – its tall windows, white-panelled doors, wooden floors, and simple mouldings – appear repeatedly. Hammershøi treated the apartment not just as a home but as a studio and a subject in itself, exploring its spaces, light, and structure with obsessive focus. He would rearrange the minimal furniture or remove it entirely to achieve the desired compositional balance and mood.

Themes and Symbolism

Beyond the formal qualities of light, colour, and composition, Hammershøi's work explores profound themes. Solitude is pervasive, not necessarily as loneliness, but as a state of quiet contemplation and self-containment. The empty rooms, the solitary figures, the pervasive silence – all contribute to an atmosphere of introspection. His paintings invite viewers into a world removed from the noise and bustle of modern life, a space for quiet reflection.

Time, or rather timelessness, is another key theme. The stillness of the scenes, the way light seems suspended, creates a sense of moments frozen outside the normal flow of time. The sparsely furnished rooms, often devoid of contemporary clutter, further enhance this feeling of enduring calm. While rooted in specific locations, the paintings transcend the particular, touching on universal human experiences of domesticity, solitude, and the passage of life.

While Hammershøi himself was famously taciturn and rarely discussed the meaning of his work, critics and historians have often found symbolic resonance in his paintings. The recurring motif of the window or the open door can be interpreted as thresholds between inner and outer worlds, between the private domestic space and the world beyond, or even between the known and the unknown. Light itself can be seen symbolically, perhaps representing clarity, spirituality, or the ephemeral nature of existence, as suggested in works like Sun Ray in the Ballroom. The back-turned figures might symbolize introspection, mystery, or the inherent unknowability of others. His work connects with the broader Symbolist movement, which favoured suggestion and mood over direct narration, sharing sensibilities with artists like Fernand Khnopff or Odilon Redon, though Hammershøi's symbolism is always grounded in a tangible reality.

Influences and Artistic Context

As mentioned, the influence of 17th-century Dutch masters, particularly Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch, is undeniable. Hammershøi admired their mastery of light, their ordered compositions, and their focus on intimate domestic scenes. He travelled and studied older art, absorbing lessons from the past. However, he was not merely imitating; he translated these influences into a distinctly modern idiom. His compositions are often more radically simplified, his palette more restricted, and his mood more melancholic and psychologically charged than his Dutch predecessors.

While aware of contemporary European art movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Hammershøi remained largely independent of them. His aesthetic concerns aligned more closely with Tonalism, as practiced by Whistler, emphasizing atmosphere and refined colour harmonies over objective representation or expressive brushwork. He can also be seen in the context of Intimism, a style associated with French painters like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who also depicted intimate domestic scenes. However, Hammershøi's work lacks the vibrant colour and decorative patterning often found in the work of the Nabis; his focus remained on structure, light, and a more austere, contemplative mood.

He was a contemporary of Edvard Munch, the great Norwegian Expressionist, but their artistic paths diverged significantly. While Munch explored raw emotion and psychological turmoil through expressive colour and distorted forms, Hammershøi pursued quietude and formal harmony, internalizing emotion rather than externalizing it.

Beyond Interiors: Landscapes and Portraits

Although best known for his interiors, Hammershøi also produced significant landscapes and portraits. His landscapes often depict architectural subjects – buildings, squares, and streets in Copenhagen, London, or Italy – or stark, minimalist views of the Danish countryside. Like his interiors, these works are characterized by a muted palette, simplified forms, and a sense of stillness and emptiness. He often chose overcast days or twilight hours, favouring diffuse light and long shadows, creating scenes of quiet grandeur or desolate beauty. Notable examples include views of Christiansborg Palace or the Asiatic Company building in Copenhagen.

His portraiture, while less extensive than his interiors, is equally distinctive. From the early portrait of his sister Anna to later works, he brought the same psychological intensity and compositional rigor. A major work in this genre is Five Portraits (1901-1902), a large group portrait depicting fellow artists and intellectuals, including his brother Svend Hammershøi, Carl Holsøe (another painter of quiet interiors), Peter Ilsted, and the architect Thorvald Bindesbøll. Even in this group setting, a sense of individual isolation and quiet contemplation prevails.

Technique and Experimentation

Hammershøi was a meticulous craftsman. His technique involved careful drawing, precise composition, and the application of paint in thin, smooth layers, often creating a subtle texture that enhances the play of light on surfaces. He worked slowly and deliberately, often returning to the same subjects repeatedly, exploring slight variations in light, angle, or arrangement. There is evidence suggesting he may have used photography as an aid in composing some works, capturing specific light effects or architectural details, though his paintings are never mere transcriptions of photographs.

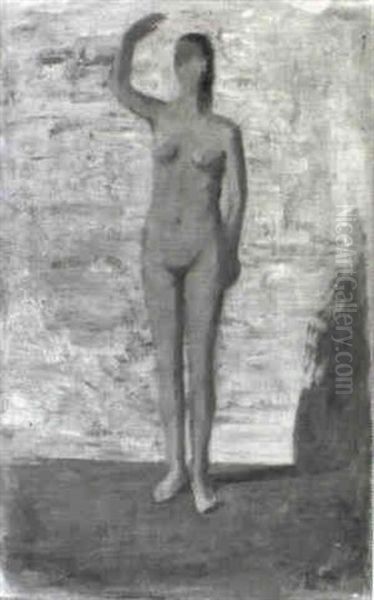

While largely consistent in his style, he did undertake some experiments, particularly later in his career. The aforementioned Five Portraits was ambitious in scale and subject matter. He also produced two rare nude studies around 1909, depicting Ida. These works, exploring the human form with the same detached observation and focus on light and shadow as his interiors, were quite different from his usual output and were not exhibited during his lifetime, only coming to light decades after his death. They reveal a less-known facet of his artistic explorations. His quiet, almost reclusive nature was reflected in his working methods; he preferred the solitude of his studio and famously destroyed personal letters before his death, leaving his art as his primary testament.

Travels and Limited Interactions

Despite his reserved personality, Hammershøi did travel outside Denmark. He visited the Netherlands, Belgium, Paris, London (where he painted views of the British Museum), and Italy. These trips allowed him to study the Old Masters firsthand and provided subjects for some of his architectural landscapes. During his travels, particularly in London and Paris, he had some contact with other artists. Records mention encounters with figures like the British painters G.F. Watts and Edward Stott, and the French artist Emile Bernard.

However, these interactions do not seem to have significantly impacted his artistic direction. He remained something of an outsider, admired by a select few – including the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who planned to write an essay on him – but not deeply integrated into international artistic circles. His social life primarily revolved around a small group of friends and family in Copenhagen. He participated in major exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale and the Berlin Secession, which helped build his reputation, particularly in Germany, but he largely maintained his artistic independence.

Legacy and Recognition

During his lifetime, Hammershøi achieved a degree of recognition, especially within Scandinavia and Germany. However, after his death from throat cancer in Copenhagen on February 13, 1916, at the age of 51, his reputation gradually faded, overshadowed by the more radical movements of modernism. For much of the 20th century, he remained a relatively obscure figure outside his native Denmark.

A significant revival of interest began in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Major retrospective exhibitions in Paris (Musée d'Orsay), London (Royal Academy), New York (Guggenheim Museum), Tokyo, Hamburg, and Copenhagen brought his work to a wider international audience. Critics and art historians reassessed his contribution, recognizing the unique power and modernity of his vision. The "Vermeer of Denmark" moniker became widespread, acknowledging his technical mastery and poetic sensibility.

Today, Hammershøi is regarded as one of the most important Nordic artists of his era. His paintings are admired for their formal elegance, psychological depth, and haunting beauty. His influence can be seen not only in painting but also in photography and cinematography, where his mastery of light, composition, and atmosphere continues to inspire. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Statens Museum for Kunst (Copenhagen), the Musée d'Orsay (Paris), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the National Gallery (London), and the Tate.

Representative Works

Hammershøi's oeuvre is remarkably consistent, yet certain works stand out as particularly representative of his genius:

Interior with a Woman Reading a Letter, Strandgade 30 (1899): A quintessential Hammershøi interior featuring Ida, seen from behind, absorbed in reading near a sunlit window.

Five Portraits (1901-1902): His largest and most ambitious group portrait, showcasing his ability to handle multiple figures while retaining an atmosphere of quiet introspection.

Portrait of a Young Girl (Anna Hammershøi) (1885): His debut piece, demonstrating his early talent and distinct approach to portraiture.

Interior with Table, Bookcase, and Windsor Chair, Strandgade 30 (1900): An example of his purely architectural interiors, focusing on the play of light on objects and space.

Woman Seen from the Back (c. 1903-1904): Another iconic depiction of Ida, emphasizing mystery and the contemplative mood.

Artemis (1893-1894): An early, more Symbolist work depicting a classical theme with his characteristic restraint.

Interior, Strandgade 30 (also known as Dust Motes Dancing in the Sunbeams) (1900): A masterful study of light itself as the primary subject.

Interior with Woman at Piano, Strandgade 30 (1901): A work that achieved a record auction price, highlighting the intimate yet formal quality of his scenes.

Ida Reading a Letter (1899): Another variation on a favourite theme, showcasing subtle variations in composition and light.

Open Doors (White Doors) (1905): A minimalist composition focusing on the geometry of doorways and the passage of light between rooms.

The Music Room, Strandgade 30 (1907): Another record-breaking painting at auction, epitomizing the serene elegance of his interiors.

Hammershøi in the Art Market

Reflecting his revived critical acclaim, Vilhelm Hammershøi's works have performed exceptionally well in the international art market in recent decades. His paintings, particularly the interiors featuring Ida or the starkly beautiful empty rooms of Strandgade 30, are highly sought after by collectors and institutions.

Auction prices have steadily climbed, setting records for Danish art. In 2012, Ida Reading a Letter sold for £1.7 million (approximately $2.7 million) at Sotheby's in London. In 2017, Interior with Woman at Piano, Strandgade 30 fetched $6.2 million at Sotheby's in New York, then a record for the artist and any Danish work of art. This record was surpassed in May 2023 when The Music Room, Strandgade 30 sold for $7.65 million (over £6.1 million) at Christie's in New York. Even his landscapes command high prices, with one fetching 5.3 million Swedish Krona (approximately €5.3 million) in June 2024. This strong market performance underscores the enduring appeal and recognized importance of Hammershøi's unique artistic vision.

Conclusion

Vilhelm Hammershøi carved a unique path in European art, creating a body of work defined by its quiet intensity, formal rigor, and profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere. As a painter of silence and solitude, he transformed the familiar spaces of his Copenhagen apartments into stages for meditations on time, existence, and the subtle beauty of the everyday. Though influenced by the Dutch Golden Age and aware of contemporary currents, he remained true to his own introspective vision, developing a style that feels both timeless and distinctly modern. Once overlooked, he is now celebrated as a master of Nordic light, whose enigmatic and deeply resonant paintings continue to captivate viewers around the world.