Walter Greaves stands as a fascinating, somewhat poignant figure in the annals of British art. Born into the heart of riverside London, his life and work were inextricably linked to the River Thames and dominated by his complex relationship with the towering figure of James McNeill Whistler. Greaves was a painter and printmaker whose canvases captured a specific, vanishing era of Chelsea and the Thames, yet his legacy remains debated, often overshadowed by the man he served as both student and assistant. His story is one of talent nurtured outside conventional academies, of profound influence and collaboration, but also of bitter dispute, neglect, and eventual, partial rediscovery.

Early Life and the Thames

Walter Greaves was born in 1846 at 31 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London. This location was not merely incidental; it placed him directly on the banks of the Thames, the river that would become the central motif of his artistic life. His father, Charles William Greaves, was a boat builder and waterman. Significantly, Greaves senior had the distinction of having ferried the great J.M.W. Turner on his sketching expeditions along the river. This familial connection to both the practical life of the Thames and to one of Britain's most revered artists provides a compelling backdrop to Walter's own future path.

Growing up in this environment, Walter and his brother, Henry Greaves (who also became an artist), were immersed in the rhythms of the river. Walter initially followed in his father's footsteps, training as a boatbuilding apprentice and working as a waterman. This hands-on experience gave him an intimate, practical knowledge of the Thames – its currents, its light, its craft, and the life along its banks. Unlike artists who might approach the river purely as a picturesque subject, Greaves understood it from the inside out. This deep familiarity would later inform the authenticity and specific detail found in his paintings.

Chelsea itself, during Greaves's formative years, was transitioning. While still retaining village-like qualities and a strong connection to its riverside industries, it was increasingly becoming a bohemian enclave, attracting artists and writers. This environment, poised between working-class river life and burgeoning artistic activity, shaped Greaves's perspective. He was not formally educated in art, learning his craft initially through observation and self-directed practice, sketching the scenes and people around him.

Meeting Whistler

The pivotal moment in Walter Greaves's life occurred around 1863. He and his brother Henry encountered the American expatriate artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who had moved to Lindsey Row, Chelsea, not far from the Greaves family home. Whistler, already a charismatic and controversial figure in the London art world, known for his sharp wit and developing aesthetic theories, took an interest in the Greaves brothers. They, in turn, were captivated by Whistler's personality and artistic vision.

Whistler, always attuned to the visual potential of his surroundings, was deeply fascinated by the Thames, particularly its atmospheric conditions at twilight and night. The Greaves brothers, with their boats and intimate knowledge of the river, became invaluable to him. They began ferrying Whistler along the Thames, much as their father had done for Turner, allowing him to observe and sketch the river under various conditions. This practical assistance soon evolved into a closer artistic relationship.

Walter, in particular, became Whistler's pupil and studio assistant. This was not a formal apprenticeship in the traditional sense, but rather an immersive, if informal, tutelage. Greaves absorbed Whistler's techniques, his developing theories about colour harmony and tonalism, and his emphasis on capturing mood and atmosphere over literal representation. The relationship was multifaceted: Greaves was part student, part assistant, part boatman, and part companion.

The Whistler Years

For nearly two decades, Walter Greaves worked closely with Whistler. His role extended beyond rowing the master on the Thames. He became an indispensable part of Whistler's studio practice. Greaves prepared canvases, mixed paints according to Whistler's specific requirements, squared up drawings for transfer, and generally assisted in the day-to-day running of the studio. He and Henry often supplied Whistler with materials, sometimes running up significant credit on his behalf.

This period saw the creation of some of Whistler's most iconic works, particularly the Thames nocturnes. Greaves was present during the conception and execution of many of these paintings. He witnessed firsthand Whistler's method of painting from memory, his meticulous application of thin layers of paint (his famous "sauce"), and his pursuit of subtle tonal harmonies to evoke the mystery and beauty of the river at night. Titles like Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75) emerged from this period of intense focus on the Thames.

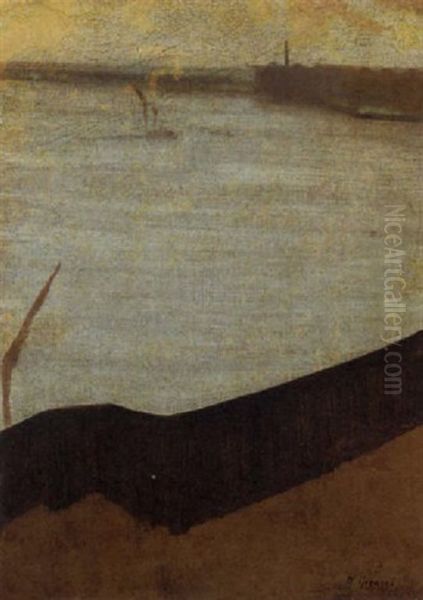

The influence was undeniably profound. Greaves began painting his own views of the Thames, heavily influenced by Whistler's style. He adopted the low viewpoints, the simplified compositions, the limited palettes dominated by blues, greys, and greens, and the focus on atmospheric effects. He painted nocturnes, twilight scenes, and daytime views of the river, often depicting the same locations Whistler favoured, such as Battersea Bridge and Cremorne Gardens. There is even speculation, though difficult to prove definitively, that Greaves may have assisted Whistler directly on some canvases or provided preliminary studies. He is also documented as having helped with decorative schemes, potentially including Whistler's famous Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1876-77).

Despite the clear debt to Whistler, Greaves's work from this period often retains a distinct quality. Where Whistler sought an abstract "arrangement" or "harmony," Greaves's paintings sometimes exhibit a more direct, perhaps slightly naive, observation rooted in his lived experience of the river. His handling of paint could be less refined than Whistler's, but there is often a charm and a sense of specific place that differs from Whistler's more detached aestheticism.

Greaves's Developing Style

While immersed in Whistler's world, Walter Greaves continued to develop his own artistic voice, albeit one deeply coloured by his mentor's influence. His most significant works often predate or coincide with the peak of his association with Whistler, suggesting an innate talent that Whistler helped to shape rather than create entirely. His masterpiece is widely considered to be Hammersmith Bridge on Boat Race Day, believed to have been painted around 1862, potentially even before he met Whistler, or very early in their acquaintance. This vibrant canvas, teeming with detail and capturing the excitement of the popular London event, shows a keen observational skill and a handling of crowds and atmosphere that is quite distinct from Whistler's later, more ethereal nocturnes.

Even in his nocturnes and twilight scenes, differences emerge. Greaves often included more anecdotal detail than Whistler, grounding his scenes more firmly in the reality of the working river. His understanding of boat structures, born from his early training, sometimes manifests in the way vessels are depicted. While he adopted Whistler's tonal palette, his colour sense could occasionally be warmer or more varied, less strictly adhering to Whistler's carefully controlled harmonies. Works like Old Battersea Bridge (1874) exist in versions by both artists, offering a fascinating comparison of their approaches to the same subject.

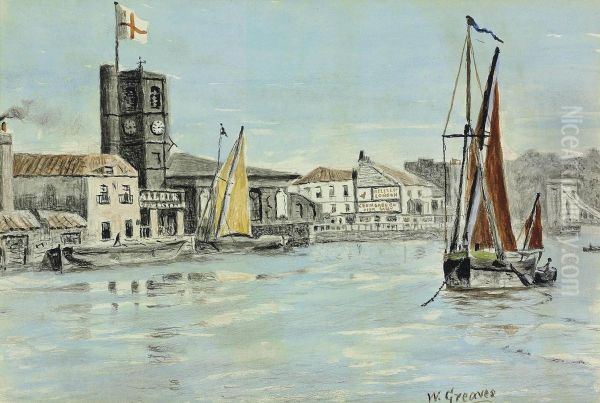

Greaves also worked in etching, another medium strongly associated with Whistler. His prints often depict the same Chelsea and Thames-side subjects as his paintings, showcasing a similar sensitivity to line and atmosphere. He captured the changing face of Chelsea, documenting its old buildings, riverside pubs, and the daily life along the embankment with an insider's eye. His topographical accuracy, while sometimes stylized, provides a valuable historical record of the area before significant redevelopment.

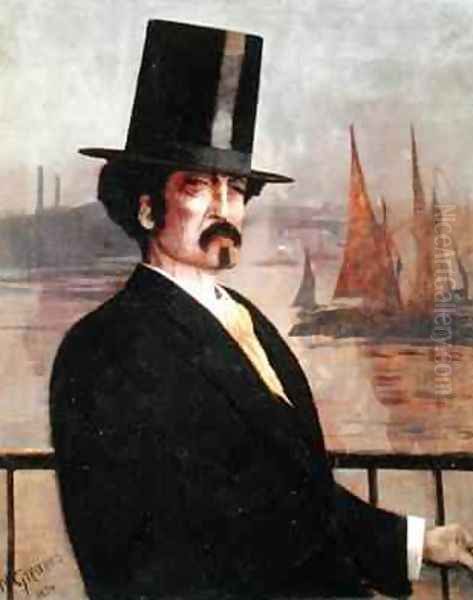

His portraits, too, show Whistler's influence, particularly in pose and composition, but often possess a directness and lack of affectation that feels personal to Greaves. He painted portraits of his family, local figures, and Whistler himself (a work titled Whistler on the Thames exists). These works demonstrate his versatility beyond landscape and nocturne.

The London Scene

Walter Greaves operated within a vibrant, complex London art world, though largely on its periphery due to his close association with the often-isolated Whistler. During the 1860s and 1870s, London was a melting pot of artistic styles. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though past its initial peak, still exerted influence; figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti were neighbours of Whistler and Greaves in Cheyne Walk. Academic painting, represented by the Royal Academy, remained dominant, promoting historical subjects and polished finishes.

Simultaneously, new ideas were arriving from France. Impressionism was beginning to make waves, and artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro spent time in London (particularly during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71), painting views of the Thames that offered a different perspective, focused on light and broken colour. Whistler himself, while often grouped with Impressionists, maintained his distinct aesthetic philosophy, emphasizing tonal harmony over the Impressionists' concern with capturing fleeting moments of light.

Within Britain, a native response to Impressionism was developing, led by artists like Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, who founded the New English Art Club in 1886 as an alternative to the Royal Academy. Sickert, initially a disciple of Whistler, later developed his own gritty, urban realism, often depicting scenes of London life. Greaves, however, seems to have remained largely insulated from these broader movements, his artistic orbit defined almost entirely by Whistler.

His subject matter remained intensely local: the stretch of the Thames between Battersea and Hammersmith, the streets and buildings of old Chelsea, the Cremorne Gardens pleasure grounds. He was, in essence, a local historian in paint, capturing a world that was rapidly disappearing. His focus was narrower than that of the Impressionists exploring wider London or the countryside, or the Academicians tackling grand themes. Yet, within his chosen milieu, his work offers a unique and authentic perspective.

The Rift and Controversy

The close relationship between Greaves and Whistler eventually fractured. As Whistler's fame and notoriety grew, particularly after the famous libel trial against the critic John Ruskin in 1878, he seems to have distanced himself from his former assistants. The Greaves brothers, who had loyally served him for years, often without formal payment, found themselves increasingly excluded from his circle. Whistler, perhaps sensitive about the extent of their earlier collaboration or simply moving in different social spheres, effectively cut ties.

Walter Greaves fell into obscurity and poverty. He continued to paint, often revisiting the Thames subjects that had defined his earlier career, sometimes working from memory. For decades, his contribution was largely forgotten by the mainstream art world. His rediscovery came about dramatically in 1911 when a portfolio of his work was found in a second-hand bookseller's shop on the King's Road by William Marchant, director of the Goupil Gallery.

Marchant, recognizing the quality and historical interest of the works, mounted an exhibition titled "The Greaves Family: Pupils of Whistler" at the Goupil Gallery in May 1911. The exhibition was a sensation, bringing Walter Greaves, then in his mid-sixties and living in poverty, suddenly into the limelight. Critics praised the naive charm and historical value of the paintings, particularly Hammersmith Bridge on Boat Race Day. Greaves enjoyed a brief period of celebrity.

However, the exhibition also ignited a fierce controversy. Joseph Pennell, an American etcher and fervent disciple of Whistler (who had died in 1903), along with his wife Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Whistler's official biographers, launched a vitriolic attack. They publicly accused Greaves of fraud, suggesting that many of the works, particularly those closely resembling Whistler's style and dating from their period of association, were either outright forgeries or works largely executed by Whistler himself, which Greaves was now falsely claiming. They questioned the dating of Hammersmith Bridge, implying it must have been painted much later under Whistler's influence.

The debate raged in the press. While some critics and artists defended Greaves, citing the unique qualities in his work and the plausibility of his long association with Whistler, the Pennells' accusations cast a long shadow. They portrayed Greaves as an untalented imitator at best, a deceitful opportunist at worst. This controversy significantly damaged Greaves's reputation just as it seemed poised for revival. Although another exhibition was held at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1922, and he received some support from fellow artists like Augustus John, Greaves never fully escaped the cloud of suspicion.

Rediscovery and Later Life

The 1911 Goupil Gallery exhibition, despite the ensuing controversy, marked a significant moment of rediscovery for Walter Greaves. It brought his work, particularly his early depictions of the Thames and Chelsea, to public attention after decades of neglect. The show included paintings, watercolours, and etchings, showcasing the breadth of his output and his intimate connection to his local environment. Works like Old Chelsea Church at Night and drawings such as The Old Archway, Chelsea highlighted his ability to capture the specific character and atmosphere of the neighbourhood.

Despite the Pennells' attacks, many recognized the genuine, if modest, talent and historical significance of Greaves's art. He received support from various quarters, including financial assistance organized by sympathetic figures in the art world. The painter Augustus John was among those who recognized his plight and talent. However, the brief fame did not translate into lasting financial security.

Greaves spent his final years in relative poverty. He was eventually admitted to the London Charterhouse, a charitable institution for elderly men. He continued to sketch and reminisce about his time with Whistler, a relationship that had defined both the peak of his artistic life and the source of his later troubles. He died at the Charterhouse in West London on November 23, 1930, aged 84. He was buried near his beloved Chelsea.

In the decades following his death, Greaves's work has undergone a gradual reassessment. While the overwhelming influence of Whistler is undeniable, art historians have increasingly recognized the independent merits of Greaves's art. His directness, his slightly archaic charm, and his value as a topographical recorder of a specific time and place are now better appreciated. His paintings offer a counterpoint to Whistler's aestheticism, providing a more grounded, less idealized view of the same riverside world.

Artistic Legacy and Evaluation

Walter Greaves's legacy is complex and inevitably tied to Whistler's shadow. He is often presented as a tragic figure, an artist whose potential was perhaps constrained by his devotion to a more famous master, and whose reputation was unfairly tarnished by controversy. Yet, his work endures and offers unique pleasures and insights.

His primary contribution lies in his evocative depictions of the River Thames and Chelsea during the mid-to-late Victorian era. He captured the working river, the pleasure gardens, the bridges, and the atmospheric effects of light and weather with an intimacy born of lifelong familiarity. Works like Hammersmith Bridge on Boat Race Day remain significant not only as charming genre scenes but also as valuable social documents. His nocturnes, while clearly indebted to Whistler, possess their own quiet poetry.

Compared to other painters of the Thames – from Canaletto and Samuel Scott in the 18th century, through his father's employer Turner, to contemporaries like Whistler and later visitors like Monet and André Derain – Greaves offers a specific, localized, and deeply personal perspective. He was not aiming for the grandeur of Turner, the analytical precision of Canaletto, or the optical experiments of the Impressionists. His art is quieter, more anecdotal, rooted in the specificities of Chelsea life.

His relationship with Whistler remains central to his story. Was he merely an imitator, or a collaborator whose contribution was later denied? The truth likely lies somewhere in between. He was undoubtedly a devoted pupil who absorbed much from Whistler, but he also possessed his own observational skills and artistic sensibility. The Pennell controversy highlights the complexities of influence, authorship, and artistic jealousy within the competitive London art world.

Today, Walter Greaves's works are held in major public collections, including Tate Britain and the British Museum, ensuring his visibility for future generations. While he may never achieve the fame of Whistler, his art provides a valuable and often charming glimpse into a specific corner of London's past, seen through the eyes of someone who knew it intimately. He remains a testament to the idea that significant art can emerge from outside the established academic system, and a poignant example of how closely intertwined talent, influence, and fortune can be in an artist's life.

Conclusion

Walter Greaves navigated a unique path through the London art world. From the boatyards of Chelsea to the studio of one of the era's most celebrated and controversial artists, his life was shaped by the River Thames and the magnetic pull of James McNeill Whistler. While his artistic output was profoundly influenced by his master, Greaves retained an individual voice, characterized by direct observation, a certain naive charm, and an invaluable record of his local environment. The controversy surrounding his 1911 rediscovery clouded his later years and complicated his legacy, but time has allowed for a more balanced appreciation of his work. He stands not merely as "Whistler's pupil," but as an artist in his own right, a chronicler of the Thames whose paintings capture the atmosphere and life of a bygone London with quiet authenticity and enduring appeal.