Introduction: Setting the Scene

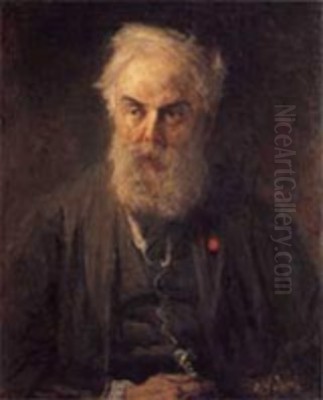

Willem Roelofs (1822-1897) stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century European art. A Dutch painter who spent a significant portion of his career in Belgium, Roelofs is celebrated primarily as a landscape artist. He is widely recognized as one of the precursors and founding fathers of the influential Hague School, a movement that revitalized Dutch painting by turning towards realism and capturing the unique atmosphere of the Dutch countryside. Furthermore, his embrace of outdoor painting techniques and his sensitivity to light and atmosphere played a crucial role in paving the way for Impressionism in the Netherlands. His life and work bridge the gap between the lingering Romanticism of the early nineteenth century and the modern approaches to art that emerged in its latter half.

Roelofs was not merely a painter; his interests extended to the natural sciences, particularly entomology, reflecting a deep and multifaceted engagement with the natural world he so masterfully depicted. His influence extended through his own prolific output, his teaching, and his active participation in the artistic communities of both Brussels and The Hague. His legacy is preserved not only in the numerous paintings held in major collections like the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Kunstmuseum Den Haag but also in the subsequent generations of artists he inspired, including figures as significant as Vincent van Gogh.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Amsterdam on March 10, 1822, Willem Roelofs showed artistic promise from a young age. His initial training likely occurred within the prevailing Romantic tradition of Dutch art. He studied at the Hague Academy of Art and received guidance from Hendrik van de Sande Bakhuyzen, a respected landscape and animal painter of the time. This early education would have grounded him in the techniques of detailed representation and the picturesque compositions characteristic of Dutch Romantic landscape painting, which often idealized nature.

Even in his early works, a keen eye for observation and a love for the Dutch scenery were evident. However, the artistic environment in the Netherlands during the 1840s was perhaps perceived by Roelofs as somewhat stagnant or limited in its opportunities. This perception, combined with personal factors, including reported difficulties in his romantic life, spurred a significant decision that would profoundly shape his career and artistic direction.

The Move to Brussels and Barbizon's Embrace

In 1847, at the age of 25, Roelofs made the decisive move from The Hague to Brussels. This relocation was driven by a search for fresh artistic stimuli and potentially better commercial prospects in the vibrant Belgian capital. Brussels at the time was a more cosmopolitan center than The Hague, with closer ties to the burgeoning art scene in Paris. This move proved fruitful almost immediately. Roelofs quickly gained recognition in his new environment.

A significant achievement came in 1848 when he was awarded a gold medal at the Brussels Salon for two landscape paintings, reportedly including Gezicht bij Wolfheze (View near Wolfheze) and a Drents landschap (Drenthe Landscape). These works attracted high praise and were subsequently purchased by King Leopold I of Belgium, cementing Roelofs' reputation and providing him with valuable royal patronage. His success in Brussels demonstrated his technical skill and the appeal of his Dutch landscape subjects even outside his native country.

Crucially, his time in Brussels exposed Roelofs more directly to the influence of the French Barbizon School. Though he may not have visited Barbizon itself frequently in the early years, the ideas and aesthetics of painters like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-François Millet were circulating in Brussels. These artists championed realism, direct observation of nature, and painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

This encounter with the Barbizon ethos marked a turning point in Roelofs' art. He began to move away from the detailed, sometimes idealized, finish of Romanticism towards a looser, more atmospheric style. He embraced painting outdoors, setting up his easel in the fields and forests around Brussels and, during his frequent return trips, in the Dutch countryside. This practice allowed him to capture a more immediate and authentic sense of place, focusing on the interplay of light, shadow, and weather.

The Hague School: A Founding Father

While residing primarily in Brussels for four decades (until 1887), Willem Roelofs maintained strong ties with the Netherlands and its artistic developments. He frequently traveled back, especially during the summers, to sketch and paint in familiar Dutch locales like the polders near Utrecht, the lakes around Noorden and Nieuwkoop, and the heathlands of Drenthe and Gelderland. These trips kept him connected to his roots and provided the subject matter for much of his work.

Through these visits and his established reputation, Roelofs became a central figure for a younger generation of Dutch painters seeking new directions. His adoption of Barbizon principles – the emphasis on realistic depiction, tonal harmony, and capturing the mood of the landscape – resonated deeply with artists back in The Hague who were also looking to break free from academic conventions. His work served as a vital link, transmitting the progressive ideas from France and Belgium into the Dutch art scene.

Consequently, Roelofs is considered one of the pioneers of the Hague School. This movement, flourishing roughly between 1860 and 1890, brought a new realism and sensitivity to Dutch landscape and genre painting. Artists associated with the school, such as Jozef Israëls, Jacob Maris, Willem Maris, Anton Mauve, Hendrik Willem Mesdag, and Johannes Bosboom, shared a common interest in depicting the everyday reality of Dutch life and landscape with honesty and atmospheric depth. They often favored muted palettes, earning the moniker "Grey School," although this generalization doesn't fit all members equally.

Roelofs, while influential, maintained a somewhat distinct style. Although he mastered the atmospheric effects beloved by the Hague School, his palette often retained more color and clarity than some of his contemporaries. His compositions were noted for their strong structure and his particular skill in rendering the vast Dutch skies and their reflection in water. He acted as both an inspiration and a mentor, guiding younger artists like Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël, who became another significant Hague School painter, and Alexander Mollinger.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Willem Roelofs' artistic journey reflects a gradual but definitive evolution from Romanticism towards a form of Dutch Realism heavily influenced by the Barbizon School, ultimately bordering on Impressionism. His early works show the fine detail and composed quality typical of his training. However, the shift towards plein air painting fundamentally changed his approach. Working outdoors encouraged looser brushwork and a greater focus on capturing the overall impression of a scene rather than meticulous rendering of every detail.

Light became a central preoccupation for Roelofs. He was fascinated by the way light defined form, created mood, and varied under different weather conditions and times of day. In an 1865 letter to a student, H.W.M. Dettmann, he emphasized the importance of observing light in nature directly, stating his aim was to "imitate nature through emotion," suggesting a subjective interpretation rather than mere photographic copying. His paintings often feature dramatic skies, luminous water surfaces, and a palpable sense of atmosphere, whether it be the dampness after rain or the warmth of a summer day.

His technique often involved making initial sketches and studies outdoors, sometimes on small wooden panels or on paper. These captured the immediate impressions of the landscape. Back in the studio, he might work these up into larger, more finished canvases. There's evidence he sometimes painted directly onto paper which was later mounted onto canvas or panel, a practice that could contribute to the freshness and texture of his work.

While associated with the Hague School's often somber tones, Roelofs' palette could be quite varied. He employed earthy greens, browns, and greys typical of the Dutch landscape but often punctuated them with brighter notes, especially in his skies and water reflections. His handling of paint became increasingly free over time, using visible brushstrokes to convey texture and movement, particularly in foliage, water, and clouds. This technical freedom, combined with his focus on light and atmosphere, aligns his later work closely with the principles of Impressionism, even if he never fully adopted the broken color technique of the French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

Masterpieces and Signature Subjects

Throughout his long career, Willem Roelofs produced a significant body of work, consistently focusing on the landscapes he knew and loved. Certain subjects appear repeatedly, becoming signatures of his oeuvre. He was particularly drawn to the flat, water-rich landscapes of the Netherlands – the polders, ditches, canals, and lakes, often under expansive, cloud-filled skies. Cattle grazing peacefully by the water's edge became a recurring motif, adding a sense of pastoral tranquility and scale to his scenes.

Among his representative works, several stand out:

View near Wolfheze (c. 1848): One of the early works that gained him recognition in Brussels, likely showcasing his skill in capturing the specific character of the Gelderland landscape, possibly still showing strong Romantic influences but hinting at the realism to come.

In 't Gein (various versions, e.g., 1850s-1860s): Depicting the area along the Gein river near Abcoude, these paintings exemplify his love for the typically Dutch waterscape, often featuring windmills, farmhouses, and reflections in the calm water under broad skies. These works show his developing mastery of atmosphere and light on water.

The Rainbow (1873): This painting captures a dramatic, transient moment in nature. The depiction of the rainbow against a stormy sky showcases Roelofs' sensitivity to changing weather effects and his ability to infuse a landscape with emotional resonance. It demonstrates a move towards capturing fleeting moments, akin to Impressionist concerns.

The Cattle Herder (1878): A mature work likely reflecting the full influence of the Barbizon school and his Hague School sensibilities. It would typically feature a pastoral scene, perhaps with cattle near water, rendered with attention to naturalistic detail, atmospheric perspective, and a harmonious, tonal palette, embodying the quiet beauty of the Dutch countryside.

Three Cows by a Pond (c. 1880-1885): This watercolor highlights his skill in this medium. Watercolors allowed for spontaneity and luminosity, qualities Roelofs exploited to capture the freshness of a scene. Such works often display clear lines combined with soft washes of color, demonstrating his fine observational skills and love for simple, rural motifs.

These works, and many others like them, consistently explore the relationship between land, water, and sky, capturing the unique essence of the Dutch landscape with both realism and poetic feeling. His focus on specific locations like Drenthe, the Utrecht lakes, and the environs of The Hague provides a valuable visual record of the Dutch countryside in the 19th century.

Beyond Painting: Entomology and Versatility

Willem Roelofs' engagement with the natural world was not confined to his artistic practice. Unusually for a painter of his stature, he was also a dedicated and knowledgeable entomologist, specializing in beetles (Coleoptera). This scientific pursuit ran parallel to his artistic career. He collected specimens, studied them meticulously, and even published scientific papers on entomology. He built up a significant collection of Curculionidae (weevils or snout beetles).

This dual passion for art and science offers a fascinating insight into Roelofs' character. His detailed observation skills, honed perhaps by scientific study, undoubtedly informed his painting, allowing him to render natural forms with accuracy. Conversely, his artistic sensibility may have enhanced his appreciation for the beauty and complexity of the insect world. This combination of interests underscores his profound connection to nature in all its aspects, from the grand scale of landscapes to the minute detail of an insect's form.

Furthermore, Roelofs was a versatile artist who worked proficiently in several media beyond oil painting. He was a skilled watercolorist, as evidenced by his role in co-founding the Société Royale Belge des Aquarellistes in Brussels in 1856. Watercolor allowed him a different kind of spontaneity and luminosity, well-suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and weather.

He also practiced printmaking, producing etchings and lithographs. These media allowed for wider dissemination of his images and offered different expressive possibilities. His prints often explore the same landscape themes as his paintings, translated into the linear and tonal language of etching or lithography. This versatility across different media demonstrates the breadth of his technical skills and his commitment to exploring various avenues of artistic expression.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Influence and Exchange

Willem Roelofs was deeply embedded in the artistic networks of his time, both in Brussels and The Hague. His move to Brussels placed him in a dynamic environment where he interacted with Belgian artists like François-Auguste Ortmans and Louis Dubois, as well as other expatriate Dutch painters. His role in founding the Watercolour Society further integrated him into the Belgian art scene.

His connection to the Barbizon School's ideas was crucial. While direct personal friendships with the core French Barbizon painters might have been limited, their work and philosophy were highly influential, likely discussed and disseminated within the Brussels art circles Roelofs frequented. His own work then became a conduit for these ideas back into the Netherlands.

In the context of the Hague School, Roelofs was both a respected elder figure and a colleague. He maintained friendships with key members like Hendrik Willem Mesdag, whom he had met in Brussels and encouraged early in his career. He also taught and influenced Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël, who shared Roelofs' interest in capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Dutch polder landscape. His relationship with Anton Mauve, another leading Hague School figure (and a cousin-in-law of Vincent van Gogh), would have been one of mutual respect within the movement.

The influence flowed both ways. While Roelofs brought Barbizon influences to the Hague School, he was also part of the collective spirit of the movement, sharing its focus on Dutch themes and realistic depiction. His interactions with figures like Jacob Maris and Willem Maris, known for their atmospheric landscapes and animal paintings respectively, were part of the ongoing dialogue that shaped Dutch art in the latter 19th century. Even Johan Barthold Jongkind, another Dutch precursor of Impressionism who worked mostly in France, shared a similar sensibility towards light and atmosphere, representing a parallel development.

Roelofs' impact extended to the next generation. His realistic yet atmospheric landscapes were studied and admired by many younger artists. Notably, Vincent van Gogh, during his early years in The Hague, deeply respected the Hague School painters, including Roelofs and Mauve. Van Gogh's early work clearly shows their influence in its subject matter and tonal approach, before he developed his unique Post-Impressionist style.

Teaching and Legacy

Beyond his own artistic production, Willem Roelofs made a significant contribution as a teacher and mentor. Having established himself successfully, he attracted numerous students eager to learn his approach to landscape painting. His studio, whether in Brussels or during his visits to The Hague, became a place of learning for aspiring artists.

Among his notable pupils were Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël, who became a distinguished landscape painter in his own right, closely associated with the Hague School but developing his own clearer, brighter style. Hendrik Willem Mesdag, later famous for his seascapes and the Panorama Mesdag, received crucial early encouragement and possibly instruction from Roelofs in Brussels before dedicating himself fully to art. Alexander Mollinger was another pupil who absorbed Roelofs' methods. His correspondence with students like H.W.M. Dettmann reveals his thoughtful approach to teaching, emphasizing direct study from nature combined with personal feeling.

Roelofs' legacy also extends through his own family. Two of his sons followed him into artistic careers. Willem Roelofs Jr. (also known as Willem Elisa Roelofs, 1874-1940) became a painter and draughtsman, often working in a style reminiscent of his father's later work. Albert Roelofs (1877-1920) also became a painter, known for portraits and genre scenes, as well as landscapes, demonstrating the continuation of artistic talent within the family.

The broader legacy of Willem Roelofs lies in his crucial role in transforming Dutch landscape painting. By integrating the realism and plein air practices of the Barbizon School, he revitalized a genre that had become somewhat formulaic. He helped foster the environment from which the Hague School emerged, setting a standard for atmospheric realism and sensitivity to the nuances of the Dutch landscape. His work provided a vital bridge to Impressionism in the Netherlands, influencing generations of artists who sought to capture the modern world and the effects of light with greater immediacy.

Roelofs' Enduring Place in Art History

Willem Roelofs occupies a secure and important place in the narrative of 19th-century Dutch and European art. He is remembered as more than just a skilled landscape painter; he was an innovator and a crucial transitional figure. His artistic journey mirrors the broader shifts occurring in European art, moving from the ideals of Romanticism towards a modern engagement with realism and the subjective perception of nature.

His forty-year residency in Brussels gave him a unique perspective, allowing him to absorb international influences, particularly from France, and channel them back into the Dutch art world. This position as an intermediary was vital for the development of the Hague School, which represented a major resurgence of Dutch painting on the international stage. While perhaps not as radically innovative as the French Impressionists, Roelofs' commitment to outdoor painting and his focus on light and atmosphere were progressive for their time and context.

His dual identity as an artist and an entomologist adds a unique dimension to his profile, highlighting a deep, analytical, yet passionate connection to the natural world. His versatility across oil painting, watercolor, and printmaking further attests to his technical mastery and artistic curiosity.

Today, his works are appreciated for their evocative portrayal of the Dutch landscape, their technical assurance, and their historical significance. Major museums in the Netherlands, including the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, hold significant collections of his paintings, ensuring his work remains accessible to the public. Auction results confirm the continued market appreciation for his art. Willem Roelofs remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of landscape painting in the 19th century and the specific character of the Hague School, a movement that defined a golden age of Dutch art. His influence, both direct and indirect, helped shape the course of Dutch painting well into the 20th century.