William Crampton Gore stands as a fascinating figure in early 20th-century Irish art, a painter whose journey from medicine to a dedicated artistic career reflects a profound personal commitment to his craft. His work, primarily focused on still lifes, interiors, and landscapes, offers a window into the artistic sensibilities of his time, bridging late Victorian aesthetics with the burgeoning influences of modern European art. Though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Gore carved out a significant niche for himself, admired for his technical skill, his subtle use of colour and light, and his ability to imbue everyday scenes with quiet dignity.

Early Life and an Unconventional Path to Art

Born in 1871 in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Ireland, William Crampton Gore's initial career trajectory was firmly rooted in the sciences. He pursued medical studies at the prestigious Trinity College Dublin, a path that led him to qualify as a doctor. He practiced medicine until around 1900, a profession demanding precision, observation, and a deep understanding of human anatomy – qualities that, while not directly artistic, often provide a unique foundation for visual artists. The discipline and meticulousness required in medicine may well have informed his later approach to painting.

However, the allure of the art world proved irresistible. Even while engaged in his medical studies and early practice, Gore's passion for painting began to take hold. In a significant life change, he began to take leave from his medical responsibilities around 1898 to travel to London. His destination was the Slade School of Fine Art, one of the most progressive and influential art institutions in Britain at the time. This decision marked a pivotal moment, signaling his shift from a secure medical career to the less certain, but evidently more fulfilling, life of an artist. He even served a brief, adventurous stint as a ship's surgeon, an experience that, while not directly documented in his art, would have undoubtedly broadened his horizons and provided unique human encounters.

The Slade School: A Crucible of Talent

The Slade School of Art in the late 1890s and early 1900s was a vibrant hub of artistic innovation, a counterpoint to the more conservative Royal Academy schools. Under the tutelage of influential figures like Henry Tonks, Philip Wilson Steer, and Frederick Brown, the Slade emphasized draughtsmanship, direct observation, and a more modern approach to painting, influenced by French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Henry Tonks, in particular, was a formidable teacher known for his exacting standards and his emphasis on anatomical accuracy and strong drawing – a discipline that would have resonated with Gore's medical background.

It was at the Slade that Gore encountered two individuals who would become lifelong friends and significant figures in British and Irish art: William Orpen and Augustus John. Orpen, known for his brilliant portraiture and later as a war artist, and John, famed for his bohemian lifestyle and expressive, powerful drawings and paintings, were leading lights of their generation. The three artists reportedly shared a studio for a time, and the dynamic, competitive, yet supportive atmosphere of the Slade undoubtedly played a crucial role in Gore's artistic development. The exchange of ideas and mutual influence among these talented young painters would have been palpable. Other notable artists associated with the Slade around this period, or slightly before and after, who contributed to its reputation, included Gwen John (Augustus's sister), Spencer Gore (no relation, a key figure in the Camden Town Group), Harold Gilman, and later, figures like Stanley Spencer and Paul Nash, highlighting the school's central role in shaping modern British art.

Crampton Gore continued his studies in painting and drawing at the Slade until 1904, thoroughly immersing himself in the techniques and artistic currents of the day. The Slade's emphasis on drawing from life and its openness to continental European influences provided a fertile ground for artists seeking to move beyond academic conventions.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

William Crampton Gore's oeuvre is characterized by a refined sensibility and a keen eye for the nuances of light and colour. He worked primarily in oils, a medium he handled with considerable skill, and his main subjects were still lifes, domestic interiors, and landscapes.

Still Life Compositions

His still life paintings are particularly noteworthy. In this genre, Gore demonstrated a talent for composition and an appreciation for the beauty of everyday objects. A work like "The Blue Bottle," exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in 1926, exemplifies his approach. While the specific visual details of this painting require direct observation, one can surmise from his general style that it would have featured a careful arrangement of objects, with attention paid to texture, reflective surfaces, and the interplay of light and shadow. The tradition of still life painting, stretching back to Dutch Golden Age masters like Willem Kalf and Pieter Claesz, and revitalized by artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin in the 18th century and later by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne and Henri Fantin-Latour, provided a rich lineage for Gore to draw upon. His still lifes likely focused on creating harmonious arrangements and exploring the tactile qualities of objects, rendered with a subtle palette.

Intimate Interiors and Genre Scenes

Gore also excelled in painting interiors and genre scenes, capturing moments of domestic life with sensitivity. His painting, "The Boiling Pot - A Cottage Interior," stands out, not least because it achieved a record auction price for his work, selling for £43,300 at Sotheby's in London in 1998. This price indicates a significant appreciation for his skill in this area. Such scenes often evoke a sense of warmth and intimacy, reminiscent of the Dutch interior painters like Johannes Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch, though filtered through a more modern, perhaps slightly Impressionistic, lens. Gore's interiors would have focused on the effects of light within a room, the arrangement of furniture, and often, a solitary figure engaged in a quiet activity, creating a narrative of everyday existence. His ability to capture the atmosphere of a room, whether humble or more appointed, was a key strength.

Landscapes: Ireland and France

Landscape painting also formed an important part of Gore's output. His Irish landscapes, such as "Old Beech Trees, Bray" (exhibited 1933), would have reflected his connection to his homeland, capturing the specific light and verdant beauty of the Irish countryside. These works can be seen in the context of a strong tradition of Irish landscape painting, which included artists like Nathaniel Hone the Younger, Walter Osborne, and later, Paul Henry and Jack B. Yeats, each of whom sought to define an Irish identity through its landscape.

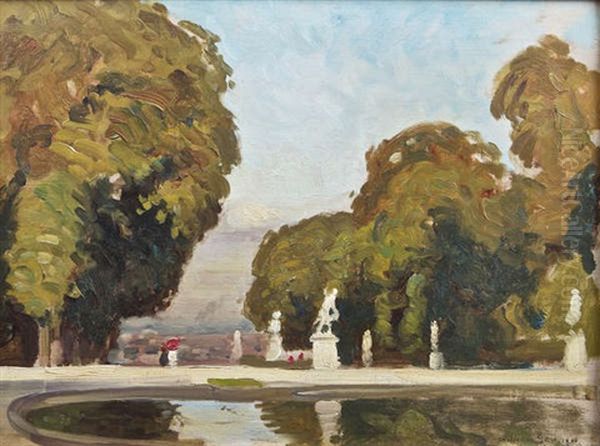

In 1923, Gore and his wife made a significant move to the South of France, where he would live until his death in 1946. This relocation would have exposed him to a different quality of light and a new range of landscapes, potentially influencing his palette and style. The South of France had long attracted artists, from Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin in Arles to Cézanne in Aix-en-Provence, and later Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard along the Riviera. While Gore's style was perhaps less radical than these modern masters, the vibrant colours and intense sunlight of the Mediterranean undoubtedly found their way into his later landscapes, such as "Saint Cloud, Paris" (though dated 1900, suggesting earlier travels or a Paris-based scene rather than the South, it indicates his engagement with French locales).

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

Throughout his career, William Crampton Gore was an active participant in the art world, particularly in Ireland. He exhibited regularly with the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in Dublin, a key institution for Irish artists. His inclusion in these exhibitions underscores his standing within the Irish artistic community. His work was also featured in significant international showcases of Irish art, including a notable exhibition in Brussels in 1937. Such exhibitions were crucial for raising the profile of Irish art abroad and demonstrating its vitality.

The continued appearance of his works at auction, and the respectable prices they command, attest to a lasting appreciation for his art. Collectors value his skilled technique, his pleasing subject matter, and his contribution to Irish painting in the early 20th century. His paintings are held in public collections, including the Limerick City Gallery of Art, ensuring their accessibility for future generations.

While Gore may not have been an avant-garde revolutionary in the vein of Picasso or Matisse, his art possesses a quiet strength and enduring appeal. He absorbed the lessons of his Slade training, particularly the emphasis on draughtsmanship and observation, and combined this with a sensitive response to his surroundings. His work can be seen as part of a broader European tradition of representational painting that continued to thrive even as modernism took hold. He shared with contemporaries like Walter Sickert (though Sickert's subject matter was often grittier) an interest in capturing the nuances of light and everyday life, albeit with a gentler, more lyrical touch.

His friendships with William Orpen and Augustus John place him at the heart of a dynamic generation of artists. Orpen, who became a highly successful society portraitist and an official war artist, and John, whose expressive and bohemian art captured a different facet of the era, both achieved greater fame. However, Gore's dedication to his chosen themes of still life, interiors, and landscapes, rendered with consistent quality and sensitivity, secured him a respected place. His decision to leave medicine for art speaks to a deep-seated passion, and his subsequent career demonstrates a steadfast commitment to his artistic vision.

In the context of Irish art, Gore contributed to a period of rich artistic production. He worked during a time when Ireland was undergoing significant cultural and political change, with movements like the Celtic Revival influencing many artists. While Gore's work does not overtly engage with the more nationalistic themes seen in some of his contemporaries like Jack B. Yeats or Seán Keating, his depictions of Irish life and landscape contribute to the broader tapestry of Irish visual culture. His connection to the RHA and his consistent exhibition record there solidify his importance within the institutional framework of Irish art.

Conclusion: A Quiet Master of Irish Art

William Crampton Gore's artistic journey is a testament to the power of personal conviction and the enduring appeal of skillfully rendered, observational painting. From his early training in medicine to his dedicated pursuit of art at the Slade School and his subsequent career in Ireland and France, Gore developed a distinctive voice. His still lifes celebrate the beauty of the mundane, his interiors evoke a sense of peace and domesticity, and his landscapes capture the essence of place, whether the soft light of Ireland or the brighter climes of France.

He navigated a period of immense artistic change, with the echoes of Impressionism giving way to Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. While Gore remained largely within a representational framework, his work is imbued with a modern sensibility in its handling of light and colour and its focus on personal observation. His friendships with major figures like Orpen and John, and his tutelage under Henry Tonks, place him within a significant lineage of British and Irish art.

Today, William Crampton Gore is remembered as a fine painter whose works continue to be admired for their technical assurance, their subtle beauty, and their honest depiction of the world around him. He may not have sought the limelight in the same way as some of his peers, but his contribution to Irish art is undeniable, offering a legacy of quiet mastery and dedication to the craft of painting. His life and work remind us that artistic significance can be found not only in grand gestures and radical innovation but also in the consistent, thoughtful exploration of the visible world.