William Cruikshank stands as a figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art history whose contributions, particularly in the realm of Canadian art education, are noteworthy, yet often overshadowed by the immense fame of his near-namesake, the British caricaturist George Cruikshank. Born in Scotland in 1848 and passing away in 1922, this William Cruikshank forged a distinct path as a painter and, significantly, as a long-serving instructor who shaped a generation of Canadian artists. Understanding his specific role requires careful separation from other individuals bearing the same surname, a confusion explicitly highlighted even in historical summaries. This exploration focuses solely on William Cruikshank, the painter and educator, piecing together his life and impact from the available records.

His artistic output included paintings and watercolours, often focusing on subjects like landscapes and detailed studies of birds. Works such as Dead Chaffinch and Dead Female Bullfinch, executed in watercolour and potentially oil pastel, exemplify this aspect of his practice. Like most artists of his time, he typically signed his works, leaving a mark of authorship on his creations. While perhaps not reaching the blockbuster prices of some contemporaries, his art retains value and appears on the auction market, with examples like a painting of a dead peacock indicating his continued engagement with natural subjects.

Distinguishing William Cruikshank

It is absolutely crucial to differentiate William Cruikshank (1848-1922), the subject of this article, from other prominent figures named Cruikshank. The most significant point of confusion arises with George Cruikshank (1792-1878). George was a towering figure in British art, renowned for his prolific output of satirical and political caricatures, book illustrations (famously for Charles Dickens, including Oliver Twist), and later, his fervent temperance-themed works like The Bottle and The Worship of Bacchus. George's style was graphic, often humorous or grotesque, and deeply embedded in the social and political commentary of Victorian Britain. His influence, collaborations, artistic rivalries (like with James Gillray), and even public disputes belong entirely to him, not to the William Cruikshank discussed here.

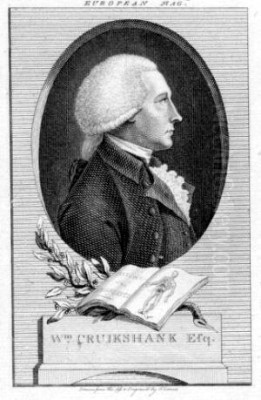

Furthermore, historical records sometimes mention William Cumberland Cruikshank (1745-1800), a distinguished Scottish physician and anatomist, known for his work The Anatomy of the Absorbing Vessels of the Human Body. He belongs to the field of medicine, not painting, and lived much earlier. The source material referenced explicitly warns against conflating these individuals, noting that William M. Cruikshank, a scholar in special education, is yet another distinct person. Our focus remains steadfastly on the painter and educator born in 1848.

Early Life and Emigration to Canada

William Cruikshank was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1848. Information regarding his early artistic training in Scotland is limited in the provided sources. However, Edinburgh in the mid-19th century possessed a vibrant artistic environment, home to the Royal Scottish Academy and various established artists. It is plausible he received foundational training there before making a life-altering decision.

In 1871, Cruikshank emigrated from Scotland to Canada. This move placed him within a broader pattern of transatlantic migration during the 19th century, where individuals sought new opportunities in developing nations like Canada. For artists, this often meant navigating a less established art market but also finding potential roles in building cultural institutions. His arrival in Canada marked the beginning of a new chapter, one where his most significant contributions would be made.

A Long Career in Art Education

Shortly after arriving in Canada, William Cruikshank embarked on a long and influential career as an art educator. He became an instructor at the Ontario College of Art (OCA) in Toronto, now known as OCAD University. This institution was central to the development of professional art training in English-speaking Canada. Cruikshank's tenure there was substantial, lasting for a remarkable twenty-five years.

His role as a teacher appears to be his most enduring legacy. During his quarter-century at OCA, he taught and mentored numerous students who would go on to become significant figures in Canadian art history. Among his most notable pupils were J.E.H. MacDonald and Franklin Carmichael. Both MacDonald and Carmichael later became founding members of the iconic Group of Seven, a collective that revolutionized Canadian landscape painting in the early 20th century.

The source material also suggests a possible connection as a teacher to Tom Thomson, another pivotal figure associated with the Group of Seven, although Thomson's formal art education was somewhat intermittent. Cruikshank's other students likely included many aspiring artists of the period, absorbing his technical knowledge and artistic perspective. His colleagues at OCA might have included figures like G.A. Reid, another influential educator and painter. Cruikshank's teaching thus played a direct role in shaping the skills and outlook of artists who would define a distinctly Canadian school of painting. His influence was perhaps less public than that of a exhibiting star, but deeply impactful through his pedagogical work.

Artistic Style and Subjects

Based on the available information, William Cruikshank worked primarily as a painter and watercolourist. His subject matter included landscapes, a popular genre in both British and Canadian art of the period. He also demonstrated a specific interest in detailed studies of nature, particularly birds. The titles Dead Chaffinch and Dead Female Bullfinch strongly suggest a practice involving careful observation and potentially still-life arrangements featuring natural specimens. This aligns with certain academic traditions emphasizing close study from life.

His use of watercolour and oil pastel indicates a versatility in media. Watercolour was a highly respected medium, particularly for landscape and detailed studies, while oil pastel offered opportunities for richer colour and texture. The mention that he signed his works is standard practice, but confirms his professional identity as an artist producing finished pieces for potential exhibition or sale.

While detailed stylistic analysis is hampered by the limited number of works specifically identified in the source material, his role as a long-term instructor at a formal art college suggests his own style likely leaned towards the academic or naturalistic conventions prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This would stand in stark contrast to the graphic, satirical, and often exaggerated style of George Cruikshank. William's art was likely more focused on representational accuracy, traditional composition, and potentially the atmospheric qualities found in landscape painting influenced by British or perhaps Barbizon school aesthetics, rather than the biting social commentary of the caricaturist. The auction estimate mentioned (£150-£200 for a dead peacock painting) suggests his work was competently executed and held a modest but respectable place in the art market of its time or later.

Representative Works: A Matter of Record

Identifying the definitive "masterpieces" of William Cruikshank (1848-1922) is challenging based on the provided information, which primarily highlights his teaching role and distinguishes him from George Cruikshank. The only specific works firmly attributed to this William Cruikshank in the source text are the bird studies:

Dead Chaffinch

Dead Female Bullfinch

These titles point towards his interest in natural history subjects and likely represent his skills in detailed rendering, probably in watercolour.

It is critical to reiterate that many famous works often incorrectly associated with the name "Cruikshank" in general searches belong to George Cruikshank. These include the narrative temperance series The Bottle (1847) and The Drunkard's Children (1848), the large allegorical painting The Worship of Bacchus (1863), numerous political cartoons like The Royal Extinguisher, and illustrations for authors like Charles Dickens (Oliver Twist, Sketches by Boz), William Harrison Ainsworth (Jack Sheppard, The Miser's Daughter), Sir Walter Scott, the Brothers Grimm, and William Hone. These are cornerstones of George Cruikshank's fame and are entirely separate from the oeuvre of William Cruikshank, the Canadian educator. The scarcity of readily available information on major, widely recognized works by William Cruikshank (1848-1922) suggests his primary impact may indeed lie more in his teaching than in a prolific public exhibition record.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping Canadian Art

The most significant and undeniable legacy of William Cruikshank (1848-1922) lies in his profound influence as an art educator in Canada. His 25-year commitment to teaching at the Ontario College of Art provided stability and foundational training for a crucial generation of Canadian artists.

His direct impact on J.E.H. MacDonald and Franklin Carmichael is particularly noteworthy. These two artists were instrumental in forming the Group of Seven, whose members sought to create a unique Canadian visual identity through landscape painting, moving away from European conventions. While the Group's mature style, characterized by bold colours, simplified forms, and a focus on the rugged Canadian wilderness, evolved beyond what Cruikshank likely taught in his academic setting, the fundamental skills in drawing, painting, and composition they acquired under his tutelage were essential building blocks. Teachers like Cruikshank provided the technical grounding upon which later innovations could be built.

The potential connection to Tom Thomson, whose evocative depictions of Algonquin Park prefigured and inspired the Group of Seven, further underscores Cruikshank's position within this pivotal network. Even if Thomson's time under Cruikshank was brief or informal, Cruikshank's presence at OCA placed him at the heart of Toronto's burgeoning art scene, where these future luminaries converged.

His influence extended beyond just the famous names. For a quarter-century, countless students passed through his classes, absorbing principles of art-making that would disseminate through the Canadian art world. He was part of the institutional framework, alongside contemporaries like G.A. Reid, C.W. Jefferys (known for his historical illustrations), and J.W. Beatty (another influential teacher and painter), that professionalized art practice and education in Ontario. While artists like Homer Watson or Lucius O'Brien represented earlier phases of Canadian landscape painting, Cruikshank was teaching the generation that would soon redefine it. His legacy is therefore less about specific canvases hung in major galleries and more about the human infrastructure of Canadian art history – the skills and encouragement passed from teacher to student.

The Challenge of the Historical Record

Researching William Cruikshank (1848-1922) presents certain challenges, largely stemming from the factors already mentioned. The overwhelming fame of George Cruikshank inevitably casts a long shadow, leading to frequent misattributions and making it difficult to isolate information pertaining solely to the Scottish-Canadian painter. Search results and even some databases may conflate the two, requiring careful cross-referencing and attention to dates and biographical details.

Furthermore, his primary contribution appears to have been in teaching. While vital, the day-to-day work of an art instructor often leaves a less dramatic public trace than that of a constantly exhibiting artist or a controversial caricaturist. Records of his specific teaching methods or pedagogical philosophy might exist within institutional archives (like those of OCAD University) but may not be as widely accessible as published critiques or monographs on exhibiting artists.

His own artistic output, focusing on potentially quieter subjects like landscape and nature studies, may not have generated the same level of contemporary discussion or subsequent scholarly attention as more provocative or stylistically radical work. The art world of late 19th-century Canada was also still developing its own critical and historical apparatus. Consequently, while his impact through his students is clear, reconstructing a detailed picture of his personal artistic career requires dedicated research and a careful sifting of the available, sometimes ambiguous, evidence.

Conclusion: An Educator's Enduring Mark

William Cruikshank (1848-1922) emerges from the historical record not as a revolutionary artist in his own right, but as a dedicated and profoundly influential educator who played a crucial role in the development of Canadian art. Born in Edinburgh, his move to Canada in 1871 led to a distinguished 25-year teaching career at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. His work as a painter and watercolourist, focusing on landscapes and nature studies like Dead Chaffinch, reflected the artistic interests of his time.

His most lasting contribution, however, was the shaping of a generation of artists. By teaching foundational skills to students like J.E.H. MacDonald and Franklin Carmichael, he indirectly contributed to the formation of the Group of Seven and the subsequent trajectory of Canadian landscape painting. While often confused with the famous British caricaturist George Cruikshank – whose life, works, and controversies are entirely separate – William Cruikshank carved his own niche. His legacy resides not primarily in widely reproduced masterpieces, but in the generations of artists who benefited from his long service as a teacher, making him a quiet but significant figure in the cultural history of his adopted country. His story is a reminder that influence in the art world flows not only through celebrated canvases but also through the dedicated work of education and mentorship.