William Davis, an artist whose life bridged the artistic currents of Ireland and England in the 19th century, remains a figure deserving of greater recognition. Born in Dublin in 1812, his journey into the world of art was not immediate, yet his eventual dedication produced a body of work, particularly in landscape painting, that aligns him closely with the ethos of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Though his contemporary fame was modest, modern art historical assessment has increasingly acknowledged his subtle mastery, his meticulous attention to detail, and his profound ability to capture the quiet poetry of the natural world and everyday scenes.

Early Life and a Fateful Move

The story of William Davis begins in Dublin, Ireland, a city with its own burgeoning artistic identity in the early 19th century. Initially, Davis's path seemed set for a career in law, a profession far removed from the bohemian studios of painters. However, the allure of art proved stronger, and he eventually redirected his ambitions, undertaking artistic training in his native city. During this formative period, he studied under a portrait painter, acquiring foundational skills in capturing likeness and form.

Despite these early efforts, the artistic environment of Dublin in the 1830s and early 1840s perhaps did not offer the specific opportunities or patronage Davis sought. Like many Irish artists of his generation, he looked across the Irish Sea to England, a larger and more dynamic centre for the arts. In 1842, Davis made the significant decision to relocate to Liverpool, a bustling port city that was rapidly developing its own cultural institutions and artistic community. This move would prove pivotal, shaping the remainder of his artistic career.

Liverpool: New Ground and Artistic Development

Upon arriving in Liverpool, William Davis began to immerse himself in the local art scene. The city was home to the Liverpool Academy of Arts, an institution that played a crucial role in fostering artistic talent in the North West of England. Davis's association with the Academy began relatively soon after his arrival. He started exhibiting his works there, initially focusing on still life compositions, a genre that allows for close observation and detailed rendering – skills that would later define his landscape work.

His commitment to formal artistic development continued, and from 1846 to 1849, Davis undertook training at the Liverpool Royal Institution, which housed the Academy's schools. This period of study would have further honed his technical abilities. His progress and standing within the Liverpool artistic community grew, and by 1851, he was elected a full member of the Liverpool Academy of Fine Arts. Some accounts suggest an earlier associate membership, indicating a steady integration into the city's artistic fabric from as early as 1843 or 1847.

The Influence of the Pre-Raphaelites and the Turn to Landscape

The mid-19th century was a period of significant artistic ferment in Britain, most notably with the emergence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) in 1848. Founded by young, rebellious artists including William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the PRB advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colours, and complex compositions found in Quattrocento Italian art, rejecting what they saw as the formulaic and overly idealized art promoted by the Royal Academy, which they felt followed too slavishly in the footsteps of artists like Raphael.

The Pre-Raphaelite ideals of "truth to nature," meticulous detail, and the depiction of serious, often moralising, subjects resonated far beyond London. Liverpool, in particular, became a significant provincial centre receptive to Pre-Raphaelite ideas. The Liverpool Academy, where Davis was now a prominent member, even awarded prizes to Pre-Raphaelite works, much to the consternation of more conservative art critics.

It was within this environment that William Davis's art underwent a significant transformation. While he had initially exhibited still lifes, he increasingly turned his attention to landscape painting. A key figure in this transition may have been the Liverpool landscape painter Robert Tonge. Tonge is said to have influenced Davis's shift towards landscape and even accompanied him on sketching trips to Ireland, allowing Davis to revisit his homeland with a painter's eye, focused on capturing its specific natural beauty.

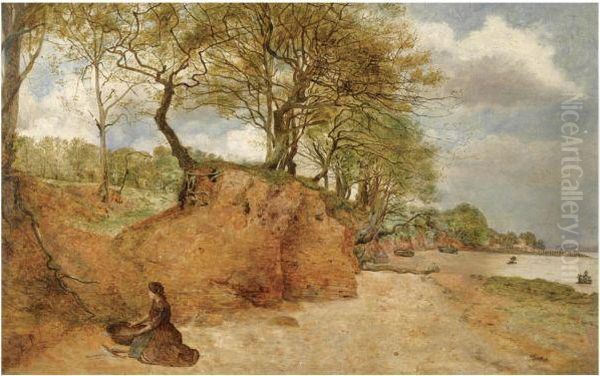

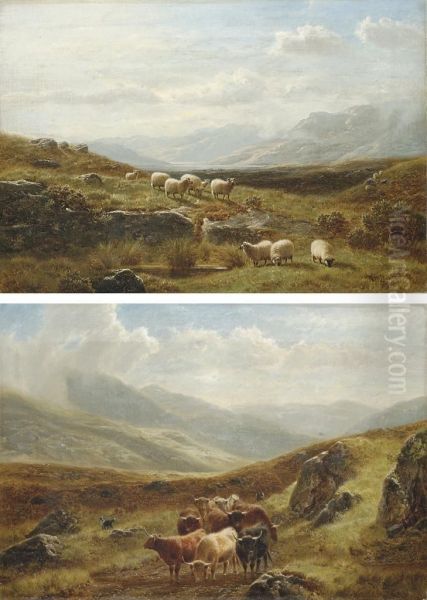

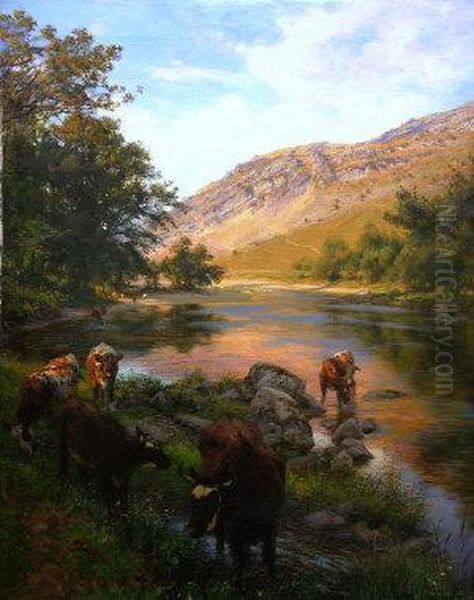

Davis's approach to landscape painting became deeply imbued with Pre-Raphaelite principles. He developed a style characterized by its extraordinary attention to detail, a patient and almost microscopic observation of the natural world. His works often featured humble, everyday scenes – a quiet corner of a field, a rustic mill, the texture of bark on a tree, or the subtle play of light on water. This focus on the "ordinary" was a hallmark of much Pre-Raphaelite landscape, which sought to find beauty and significance in the commonplace, rendered with utmost fidelity.

Artistic Style: Detail, Light, and Sincerity

The mature style of William Davis is distinguished by its meticulous technique and a profound sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere. He eschewed the grand, Claudian vistas favored by earlier generations of landscape painters, preferring instead more intimate and closely observed scenes. His brushwork was often fine and precise, allowing him to render the intricate details of foliage, the texture of stone, or the complexities of a cloudy sky with remarkable clarity.

Light, in Davis's paintings, is not merely illustrative but an active component of the composition, defining form, creating mood, and highlighting the subtle variations in colour and texture. Whether depicting the crisp light of an early spring evening or the more diffuse glow of an overcast day, his handling of light and shadow lent his works a quiet realism and a palpable sense of place.

Modern critics often praise the "sincerity" of Davis's vision. His paintings convey a deep and unassuming love for the landscapes he depicted, primarily the countryside around Liverpool, Cheshire, and North Wales, as well as scenes from his native Ireland. There is an honesty in his approach, a desire to represent the world as he saw it, without artificial embellishment or overt romanticism. This commitment to truthfulness, even in the depiction of the most mundane subjects, aligns him closely with the core tenets of Pre-Raphaelitism as championed by figures like John Ruskin, the influential art critic who famously urged artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing."

However, it's worth noting that while Davis's meticulousness was Pre-Raphaelite in spirit, his choice of often very humble, unadorned subjects sometimes led to a cooler reception from critics like Ruskin himself, who, despite his call for truth to nature, could also find some highly detailed works lacking in grander compositional ambition or overt moral narrative. Ruskin reportedly found some of Davis's work "too prosaic."

Key Works and Exhibitions

Throughout his career, William Davis produced a significant body of work, though many pieces may now be in private collections or lesser-known public galleries. Among his notable paintings, several stand out as exemplars of his style.

"Early Spring Evening, Cheshire" (circa 1855) is a prime example of his Pre-Raphaelite influenced landscape. Such a work would likely showcase his ability to capture the specific quality of light and the nascent beauty of the season with painstaking detail, from the individual blades of grass to the delicate tracery of new leaves on trees.

"Wallesey Mill, Cheshire" (sometimes cited as "Walleseye, Cheshire") is another frequently mentioned piece. Mills were a common feature in the 19th-century landscape, and for an artist like Davis, they offered a combination of man-made structure and natural surroundings, allowing for a detailed study of textures – wood, stone, water, and foliage.

His "View from Bidston Hill" (circa 1865) would have offered a more panoramic perspective, likely capturing the Wirral landscape looking towards Liverpool. Such a painting would demonstrate his skill in handling broader vistas while still maintaining a high degree of detail in the foreground elements.

Other titles attributed to him further illustrate his focus on rural and local scenes: "The Shore at New Ferry," "Ploughing," "Ditton Mill," "Ireland - Cows," and "Milking Cows." These titles suggest an artist deeply engaged with the agricultural life and natural environments he encountered. He also painted still lifes, such as "Scotch Terriers," indicating a versatility beyond pure landscape.

Davis was a regular exhibitor. He showed his work consistently at the Liverpool Academy from 1842. Crucially, he also gained exposure on the London stage, exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy between 1851 and 1872. His submissions to the Royal Academy, particularly his landscapes, reportedly garnered praise from prominent Pre-Raphaelite figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown. This recognition from leading members of the movement underscores his alignment with their artistic aims, even if he was geographically somewhat removed from the core London group.

His involvement with the Liverpool Academy was not just as an exhibitor; he also served as a Professor of Painting there from 1856 to 1859, contributing to the education of a younger generation of artists in the city. Furthermore, his connections extended to London's avant-garde circles, as evidenced by his membership in the Hogarth Club in the late 1850s. The Hogarth Club was a progressive exhibiting society that included many artists associated with or sympathetic to the Pre-Raphaelite movement, such as Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes, and William Morris.

Patronage and Professional Realities

Despite the quality of his work and the respect he earned from fellow artists, William Davis did not achieve widespread fame or significant financial success during his lifetime. The art market of the Victorian era could be fickle, and tastes often favored more dramatic or sentimental subjects than Davis's quiet, detailed landscapes.

His primary patrons appear to have been two Liverpool collectors, George Rae and John Miller. Rae, a Birkenhead banker, was a notable patron of Pre-Raphaelite art, famously acquiring works by Rossetti and Brown. Miller, a Leith-born merchant based in Liverpool, also collected contemporary art. While their support was undoubtedly important, providing a degree of financial stability, Davis reportedly felt a sense of humiliation that his patronage was so limited. This suggests an artist aware of his own merit but frustrated by the lack of broader public or critical acclaim and the financial rewards that might have accompanied it.

This situation was not uncommon for artists who adhered to the demanding tenets of Pre-Raphaelitism, especially in landscape. The meticulous, labor-intensive technique required meant that paintings took a long time to produce, and if they did not find ready buyers, the artist could face considerable hardship. Artists like John Brett, another landscape painter deeply influenced by Pre-Raphaelite principles and Ruskin's writings, also experienced the challenges of balancing artistic integrity with commercial viability.

The Liverpool School of painters, of which Davis was a key member, included other talented individuals like William Lindsay Windus, known for his emotionally charged Pre-Raphaelite figure paintings, and Daniel Alexander Williamson, who also produced highly detailed landscapes. These artists collectively contributed to Liverpool's reputation as a significant centre for Pre-Raphaelite activity outside London.

Later Years, Move to London, and Legacy

In 1870, perhaps seeking new opportunities or a change of scene, William Davis moved from Liverpool to London. The capital was the undisputed centre of the British art world, and many provincial artists eventually gravitated there. However, his time in London was to be relatively short.

William Davis passed away in London on April 22, 1873, at the age of 60 or 61. The cause of his death is recorded as unknown, adding a poignant note of uncertainty to the end of his life story.

During his lifetime, Davis was a respected figure within certain artistic circles, particularly in Liverpool and among those sympathetic to Pre-Raphaelitism. However, he did not achieve the widespread renown of the leading Pre-Raphaelites like Millais, Hunt, or Rossetti, nor even the level of fame of some other landscape painters of the era. His commitment to depicting ordinary scenes with intense, almost scientific, observation may have been too subtle or too "prosaic," as Ruskin suggested, for mainstream Victorian tastes.

Yet, the passage of time has allowed for a re-evaluation of his work. Modern art historians and curators, looking back at the diverse strands of 19th-century British art, have increasingly recognized William Davis's unique contribution. He is now often cited as one of the most significant landscape painters associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, particularly within the context of the Liverpool School. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their quiet beauty, and their sincere engagement with the natural world. They stand as testaments to an artist who, with modest means and often limited recognition, pursued his vision with integrity and dedication.

His work can be found in several public collections, notably in the North West of England, including the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, which holds a significant collection of works by Liverpool School artists. These paintings allow contemporary audiences to appreciate the delicate artistry and profound observation of a painter who found enduring beauty in the everyday landscapes of Britain. He remains a compelling example of an artist whose true stature has perhaps only been fully appreciated in retrospect, a quiet master whose detailed visions of nature continue to resonate. His legacy is that of an artist who, influenced by the revolutionary spirit of the Pre-Raphaelites, forged a distinctive path in landscape painting, leaving behind a body of work that captures the subtle splendours of the 19th-century British countryside with honesty and remarkable skill. His contemporaries in the broader field of landscape included artists like Benjamin Williams Leader or Alfred de Bréanski, Sr., who often pursued more overtly picturesque or dramatic scenes, highlighting Davis's more introspective and detailed approach.

Conclusion: A Reappraisal of a Dedicated Artist

William Davis's career exemplifies the journey of a dedicated artist who, while not achieving widespread contemporary fame, remained true to his artistic principles. His move from portraiture and still life to highly detailed, Pre-Raphaelite-influenced landscapes marked him as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in 19th-century British art. His connection to the Liverpool Academy, his exhibitions at the Royal Academy, and the respect he garnered from figures like Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown, speak to his standing within the artistic community.

Though his patrons were few, and he may have felt the sting of limited recognition, his legacy endures in the quiet intensity of his canvases. These works, with their meticulous rendering of light, texture, and the subtle nuances of the natural world, offer a window into the landscapes of Victorian Britain and the artistic currents that shaped their depiction. William Davis remains a testament to the power of patient observation and the enduring appeal of "truth to nature," a core tenet of the Pre-Raphaelite vision that he so skillfully translated into his own unique artistic language. His contribution to the rich tapestry of British landscape painting, particularly within the Liverpool School, is now more fully appreciated, securing his place as a noteworthy artist of his time.