James Collinson (1825-1881) occupies a unique, if sometimes overlooked, position in the annals of British art. A founding member of the revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his artistic journey was profoundly shaped by his deep religious convictions, leading to a career characterized by both fervent creativity and periods of introspective withdrawal. His story is one of talent, spiritual searching, and a quiet dedication to his craft amidst the vibrant and often tumultuous London art world of the mid-19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on May 9, 1825, in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, James Collinson was the son of a bookseller. This environment likely provided him with early exposure to literature and imagery, potentially fostering an inclination towards the narrative and symbolic aspects that would later define his art. Seeking formal artistic training, Collinson made his way to London and enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. It was here that he would hone his technical skills and, more importantly, encounter the individuals who would become his collaborators and fellow iconoclasts.

The Royal Academy in the 1840s was still largely dominated by the classical traditions and idealized aesthetics championed by its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. While providing a solid foundation in drawing and composition, its teachings were increasingly viewed by a younger generation as staid, formulaic, and detached from genuine emotion and the realities of nature. This simmering discontent would soon boil over, leading to the formation of one of the most influential art movements in British history.

The Genesis of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

In 1848, a momentous year of revolution and change across Europe, James Collinson, alongside William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, became a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). They were soon joined by William Michael Rossetti (Dante Gabriel's brother, who acted as the group's secretary and chronicler), Frederic George Stephens (an art critic), and Thomas Woolner (a sculptor). This rebellious septet aimed to overthrow what they perceived as the triviality and academicism of contemporary British art.

The name "Pre-Raphaelite" itself was a declaration of their intent: to return to the artistic principles prevalent before Raphael and the High Renaissance. They admired the sincerity, detailed naturalism, and vibrant color of early Italian and Flemish masters like Fra Angelico, Jan van Eyck, and Sandro Botticelli. The PRB advocated for "truth to nature," meticulous detail, serious and significant subject matter (often drawn from literature, religion, or contemporary social issues), and a rejection of the conventional, often sentimental, tropes of Victorian genre painting. Their early works were characterized by bright, jewel-like colors applied to a wet white ground, sharp focus throughout the picture plane, and a complex, often symbolic, iconography.

Collinson, known for his quiet and devout nature, was perhaps an unlikely revolutionary. However, his commitment to sincerity and his skill as a painter made him a valuable early member. He was particularly drawn to subjects with a strong moral or religious component, aligning with the PRB's desire to imbue art with deeper meaning.

Collinson's Contributions to Pre-Raphaelitism

During his relatively brief tenure with the PRB, Collinson made significant contributions. He embraced the group's aesthetic principles, producing works that demonstrated a commitment to detailed observation and emotional intensity. One of his most notable early Pre-Raphaelite works was The Renunciation of St. Elizabeth of Hungary (also sometimes referred to as An Incident in the Life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary), exhibited at the National Institution (the "Free Exhibition") in 1851, though conceived and largely painted earlier.

This painting depicts the 13th-century saint, a princess who renounced her worldly status to serve the poor and sick, kneeling before an altar in a moment of profound spiritual devotion. The work is rich in Pre-Raphaelite characteristics: the meticulous rendering of fabrics, the detailed architectural setting, the earnest expressions of the figures, and the use of clear, bright colors. The subject matter itself, focusing on an act of extreme piety and self-sacrifice, resonated with Collinson's own religious sensibilities and the PRB's interest in historical and religious narratives that conveyed strong moral messages. The painting was generally well-received, with critics noting its sincerity and careful execution, a contrast to the often harsh criticism leveled at other PRB works of the period.

Collinson also contributed to the Pre-Raphaelite literary journal, The Germ: Thoughts towards Nature in Poetry, Literature and Art, which ran for four issues in 1850. He penned a long devotional poem titled "The Child Jesus: A Record Typical of the Five Sorrowful Mysteries." This poem, like his paintings, reflected his deep piety and his alignment with the PRB's aim to integrate art and literature with a sense of spiritual and moral purpose. Other contributors to The Germ included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti (his sister and a renowned poet), Coventry Patmore, and Ford Madox Brown, an older artist who, while not an official member, was a close associate and mentor to the PRB.

A Crisis of Conscience: Religion and the PRB

Collinson's deep religious faith, however, became a source of internal conflict and ultimately led to his departure from the Brotherhood. He was a devout Christian, and around the time of the PRB's formation, he converted to Roman Catholicism. This was a significant step in Victorian England, where anti-Catholic sentiment was still prevalent, despite the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. The Oxford Movement within the Church of England had, however, revived interest in Catholic traditions and liturgy, influencing many artists and intellectuals.

His faith played a crucial role in his personal life as well. He became engaged to Christina Rossetti, a poet of profound Anglican faith. Her religious scruples about marrying a Catholic led Collinson to revert to Anglicanism. However, his spiritual journey was far from over.

A turning point came with the public outcry against John Everett Millais's painting Christ in the House of His Parents (also known as The Carpenter's Shop), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850. The painting's realistic depiction of the Holy Family in a humble, working-class setting, with a young Jesus portrayed with a cut on his hand prefiguring the stigmata, was decried by critics, including Charles Dickens, as blasphemous and ugly. The intense criticism and accusations of sacrilege deeply troubled Collinson. Believing that the PRB's principles were being misconstrued as irreverent, and perhaps feeling that his own artistic endeavors within the group were incompatible with his increasingly fervent Catholic beliefs, he resigned from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1850. He subsequently reconverted to Roman Catholicism, a decision that also led to the end of his engagement with Christina Rossetti.

This period was undoubtedly one of great turmoil for Collinson. His departure marked the first break in the original Pre-Raphaelite ranks and highlighted the complex interplay of art, religion, and personal conviction that characterized the Victorian era. Artists like Augustus Pugin, a fervent Catholic convert and a leading figure in the Gothic Revival, also navigated this complex religious landscape, advocating for a return to medieval Christian art and architecture.

Art After the Brotherhood: Social Realism and Genre Scenes

Despite leaving the PRB, Collinson did not abandon his artistic career, nor did he entirely forsake the principles he had helped to establish. He continued to paint, often focusing on subjects that allowed for detailed observation and the expression of quiet emotion. He spent a period from 1852 to 1854 training as a Jesuit novice at Stonyhurst College, but ultimately decided against a clerical life and returned to his artistic pursuits.

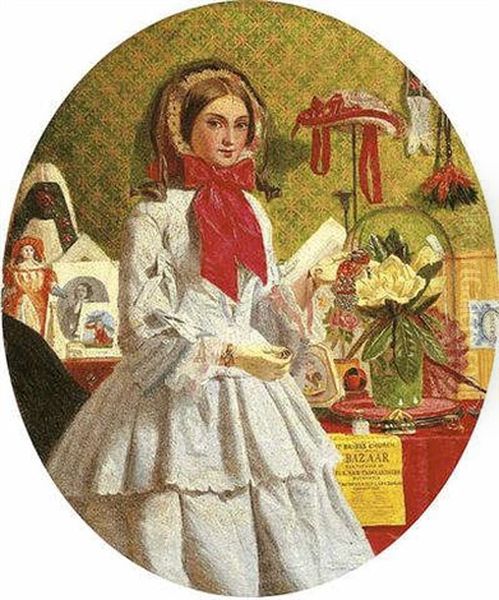

His later works often leaned towards genre scenes, depicting everyday life with a sensitivity and attention to detail that still bore the hallmarks of his Pre-Raphaelite training. Two of his most well-known paintings from this period are To Let and For Sale (both exhibited in 1857, though To Let may have been worked on over several years). These paintings, often considered a pair, depict young women in moments of quiet despair, surrounded by the evidence of their straitened circumstances.

To Let shows a young woman, possibly a widow or a governess who has lost her position, standing forlornly in an empty room with a "To Let" sign in the window. The bare floorboards, the sparse light, and her melancholic expression convey a powerful sense of loss and uncertainty. For Sale portrays a similar mood, with a young woman looking out of a window beside a "For Sale" sign, her possessions perhaps being sold off. These works demonstrate Collinson's empathy for the vulnerable and his ability to capture subtle emotional narratives. They can be seen as part of a broader trend in Victorian art towards social realism, explored by artists like Luke Fildes in Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward or Hubert von Herkomer in Hard Times. However, Collinson's approach was typically less overtly dramatic and more introspective.

Another notable work, Short Change (1858), depicts a young boy, a street vendor, looking dismayed as he realizes he has been cheated. The painting is a masterful study of childhood innocence confronted by the harsh realities of the world, rendered with the meticulous detail and psychological insight that Collinson commanded. These paintings, while not strictly "Pre-Raphaelite" in the dogmatic sense, continued to emphasize truthfulness, careful observation, and a concern for meaningful subject matter.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later career, Collinson continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy and the British Institution. He also became the secretary of the Society of British Artists (later the Royal Society of British Artists, or RBA) from 1861 to 1870. This administrative role suggests a continued engagement with the London art world, even if his own artistic output became less prominent than that of his former PRB colleagues like Millais (who became President of the Royal Academy), Hunt (who maintained a steadfast commitment to PRB ideals), or Rossetti (who moved towards a more aesthetic and symbolic style).

Compared to these figures, or later artists associated with the movement like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, who took Pre-Raphaelite ideals into the realm of decorative arts and a more dreamlike medievalism, Collinson's later career was quieter. He never achieved the same level of fame or notoriety. His deeply personal religious journey and his early departure from the PRB perhaps contributed to his somewhat more marginal position in popular art historical narratives.

James Collinson passed away on January 24, 1881, in Brittany, France, where he had been living for some years.

Artistic Style and Enduring Influence

James Collinson's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous detail, clear draftsmanship, and a quiet, often melancholic, emotional intensity. His early Pre-Raphaelite works, like The Renunciation of St. Elizabeth of Hungary, showcase the bright palette and sharp focus advocated by the Brotherhood, influenced by the "quattrocento" Italian art they admired. He shared their commitment to painting directly from nature and imbuing even small details with significance.

Even after leaving the PRB, this attention to detail and a desire for verisimilitude remained. His genre paintings, such as To Let and Short Change, demonstrate a keen observation of human emotion and social situations. While they may lack the overt symbolism or literary grandeur of some Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces, they possess a poignant honesty and a subtle narrative power. His handling of light is often delicate, and his compositions carefully constructed to enhance the emotional impact of the scene.

Collinson's legacy is perhaps more nuanced than that of his more famous contemporaries. He was a crucial early member of a revolutionary movement, and his work from that period exemplifies its core tenets. His subsequent career, though less radical, produced paintings of considerable charm and social insight. His story underscores the diversity within the Pre-Raphaelite circle and the profound impact of personal conviction, particularly religious faith, on artistic production in the Victorian era. While artists like William Dyce also successfully combined religious themes with Pre-Raphaelite precision, Collinson's journey was uniquely marked by his formal association and subsequent break with the Brotherhood over matters of conscience.

Conclusion

James Collinson remains an important figure for understanding the early formation and internal dynamics of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His art, characterized by its sincerity, meticulous craftsmanship, and deep religious feeling, offers a valuable counterpoint to the more flamboyant or secular works of some of his peers. His paintings, particularly those addressing themes of faith, social vulnerability, and quiet human drama, continue to resonate with viewers who appreciate their subtle power and heartfelt conviction. Though his path diverged from the mainstream of Pre-Raphaelitism, his contributions, both as a founding member and as an independent artist, secure his place in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. His journey reminds us that artistic movements are composed of individuals with diverse motivations and that the intersection of art, faith, and personal integrity can lead to complex and compelling creative expressions.