William Dobson (1611-1646) stands as a pivotal, if tragically short-lived, figure in the annals of British art. Often hailed as one of England's first truly great native-born painters, his career burned brightly during the tumultuous English Civil War, leaving behind a legacy of powerful portraits that capture the resolute spirit of a nation divided. His work, steeped in the Baroque tradition, offers a compelling alternative to the continental artists who had previously dominated the English court, marking him as a significant forerunner to later masters of British painting.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in London in 1611, William Dobson's early life was marked by a stark contrast between initial privilege and subsequent hardship. His family was of gentle birth and possessed considerable means, but his father, a lawyer and amateur painter, was known for his extravagant and "dissolute" lifestyle, which eventually led to financial ruin. This reversal of fortune likely compelled the young Dobson to seek a means of earning his own living, steering him towards the burgeoning world of art in London.

His formal artistic training began around 1625. He is believed to have been apprenticed first to William Peake, a painter and picture dealer, which would have provided him with exposure to various artworks. More significantly, he later entered the studio of Francis Cleyn, a German artist who was the chief designer for the Mortlake Tapestry Works. Cleyn's workshop was a hub of artistic activity, and it was here that Dobson would have honed his skills and, crucially, gained access to the Royal Collection. This access allowed him to study and copy works by Renaissance and Baroque masters, particularly the Venetian painters like Titian and Tintoretto, and the then-dominant court painter, Sir Anthony van Dyck. These encounters were formative, shaping his palette, compositional sense, and understanding of painterly technique.

The Influence of Masters and the Royal Gaze

Dobson's talent did not go unnoticed for long. While the exact circumstances are somewhat shrouded, it is widely recounted that a painting by Dobson, possibly a copy or a work in the style of Titian or Van Dyck, caught the discerning eye of King Charles I. The King, a renowned connoisseur and patron of the arts, was impressed by the young Englishman's skill. It is said that Charles I himself recommended Dobson to Sir Anthony van Dyck, the Flemish artist who had revolutionized portraiture in England with his elegant and sophisticated style.

Van Dyck, in turn, recognized Dobson's burgeoning talent. While Dobson never formally became Van Dyck's pupil in the traditional master-apprentice sense, Van Dyck's influence on him was undeniable, particularly in terms of composition and the dignified portrayal of sitters. However, Dobson was no mere imitator. He absorbed the lessons of Van Dyck and the Venetians but forged a style distinctly his own – more robust, more direct, and often imbued with a uniquely English sensibility. Van Dyck's patronage, or at least his endorsement, was instrumental in opening doors for Dobson, leading to commissions and eventually an invitation to paint for the King and his court.

Court Painter in a Kingdom Divided: The Oxford Years

The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 dramatically altered the landscape of England, and with it, the fortunes of its artists. When King Charles I was forced to leave London and establish his court in Oxford, William Dobson followed. This move proved to be a defining period in his career. With the death of Sir Anthony van Dyck in 1641, a void had been left at court. Dobson, already recognized for his abilities, stepped into this role, effectively becoming the principal painter to the King during these turbulent Oxford years.

In Oxford, Dobson was at the heart of the Royalist cause, surrounded by the key figures of the King's party – courtiers, scholars, and, most notably, the military men who were fighting for the Crown. His studio, reputedly in St John's College, became a place where these individuals were immortalized on canvas. He painted portraits of the King himself, his sons (including the young Prince of Wales, the future Charles II, and James, Duke of York), and prominent Royalist commanders such as Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a nephew of the King and a dashing cavalry leader. These portraits are not just likenesses; they are powerful statements of loyalty, resolve, and the sombre dignity of men facing uncertain futures.

Dobson's Oxford period, from roughly 1642 to 1646, represents the apex of his artistic output. The intense, charged atmosphere of a court at war seems to have fueled his creativity, resulting in some of his most compelling and psychologically astute works. He captured the gravity of the times, the determination etched on the faces of his sitters, often against backgrounds or with attributes that subtly alluded to the conflict.

A Distinctive Baroque Style: Robustness and Allegory

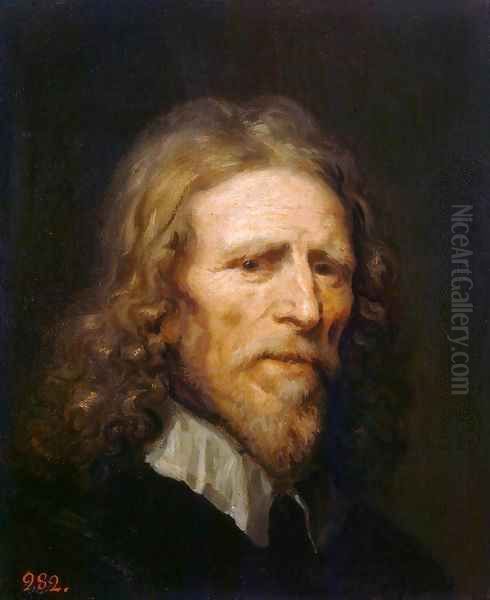

William Dobson's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Baroque, characterized by rich, often warm, colours, dynamic compositions, and a tangible sense of presence. However, he developed a personal interpretation of this international style that set him apart, particularly from his immediate predecessor, Van Dyck. While Van Dyck's portraits were celebrated for their refined elegance and elongated figures, Dobson's subjects often appear more solid, more grounded, and possess a certain ruggedness.

He frequently employed a square or near-square canvas format, often depicting his sitters from the knee up. This compositional choice contributed to the sense of weight and substance in his figures. His brushwork, especially in his earlier works, could be quite thick and impastoed, lending a textural richness to fabrics and flesh. After 1642, perhaps reflecting the increasingly grim realities of the war and his own circumstances, his paint application sometimes became thinner and his palette more melancholic, though still retaining its characteristic warmth.

A particularly innovative aspect of Dobson's portraiture was his development of a unique allegorical or symbolic language. He often incorporated objects, classical allusions, or specific settings that served to identify the sitter's character, profession, loyalties, or intellectual pursuits. This was a departure from the more straightforwardly representational approach common in much English portraiture before him and added a layer of intellectual depth to his work. These symbolic references were not merely decorative but were integral to the meaning of the portrait, offering insights into the sitter's identity within the context of their tumultuous times. This practice was unprecedented in its consistent application in English portraiture.

His debt to Venetian masters like Titian and Tintoretto is evident in his rich colour harmonies and his handling of light and shadow, creating a sense of volume and drama. Indeed, some contemporaries referred to him as the "English Tintoretto." While he learned from Van Dyck, his style retained a certain directness and a less idealized quality that some scholars have linked to a lingering Dutch influence, possibly absorbed through his early training or exposure to works in English collections. This fusion of influences, tempered by his own robust vision, resulted in a powerful and original artistic voice.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

Despite his short career, William Dobson produced a significant body of work, with several paintings now recognized as masterpieces of British art.

Perhaps his most famous work is the Portrait of Endymion Porter (c. 1642-1645), now in the Tate Britain (though often cited as National Gallery, London in older texts). Porter was a courtier, diplomat, and art collector, a key figure in Charles I's circle. Dobson depicts him in a landscape, leaning on a sculpted relief, with a hunting scene in the background. The painting is rich in symbolism, alluding to Porter's various roles and his loyalty to the King. The composition is complex, the colours warm and resonant, and Porter's expression is one of thoughtful melancholy, fitting for the times.

Another significant work is the Portrait of an Unknown Officer (sometimes identified as Colonel Richard Neville or Russell) (c. 1642-43). This painting exemplifies Dobson's ability to convey martial strength and determination. The officer, clad in armour, gazes directly at the viewer with a resolute expression. The use of a cannon and a battle scene in the background firmly places the sitter within the context of the Civil War.

His group portraits are particularly noteworthy. One such example is An Unknown Officer, Sir Charles Lucas (?), and Sir George Lisle (?) (often referred to generally as "Three Cavaliers" or similar titles depicting Royalist officers). These works capture the camaraderie and shared purpose of the King's men. The figures are typically robust, their expressions serious, and their attire and accoutrements rendered with Dobson's characteristic attention to texture and detail.

Dobson also painted notable individual portraits of key Royalist figures. His Portrait of John Byron, 1st Lord Byron (c. 1643), shows the Royalist commander with a stern, weathered face, conveying his military experience and unwavering loyalty. The Portrait of Richard Lovelace, the Cavalier poet, is another sensitive portrayal, capturing the sitter's refined yet resolute character.

His portraits of the royal children, such as Prince Rupert, Count Palatine and the Prince of Wales (later Charles II), are also important. These works, while acknowledging the sitters' youth, often imbue them with a premature gravity, reflecting the serious times in which they lived. For instance, his depiction of the young Prince of Wales, around twelve or thirteen years old, shows him in armour, a commander before his time, a poignant symbol of the conflict's reach.

These works, and many others, demonstrate Dobson's skill in capturing not just a physical likeness but also the psychological essence of his sitters, framed by the dramatic backdrop of the Civil War. His subjects often exude a sense of steadfastness and an unyielding will, qualities highly valued by the Royalist cause.

The Inevitable Decline and Tragic End

The fortunes of William Dobson were inextricably linked to those of his royal patron. As the Royalist cause began to falter, so too did Dobson's prospects. The decisive blow came in June 1646 when Oxford, the King's wartime capital, surrendered to the Parliamentarian forces led by Sir Thomas Fairfax. With the fall of Oxford, Dobson's primary source of patronage evaporated. The King was a captive, and his court was dispersed.

Dobson returned to London, a city now firmly under Parliamentarian control. His known Royalist sympathies and his association with the defeated King would have made it difficult, if not impossible, to find new patrons among the victorious party. He faced severe financial hardship. Records indicate that he was imprisoned for debt, a common fate for those who fell on hard times in the 17th century.

His health, perhaps already strained by the anxieties of war and his subsequent struggles, declined rapidly. William Dobson died in poverty in London in October 1646, at the tragically young age of 35 or 36. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields, a poignant end for an artist who had so recently been the King's principal painter. His promising career, which had shone so brightly for a few intense years, was extinguished far too soon.

Legacy and Art Historical Re-evaluation

For a considerable time after his death, William Dobson's name faded into relative obscurity, overshadowed by the towering figure of Van Dyck before him and the later rise of painters like Sir Peter Lely, who came to prominence after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Lely, a Dutchman, continued the Baroque tradition but with a smoother, more flamboyant style that appealed to the tastes of Charles II's court.

However, in more recent times, art historians have undertaken a significant re-evaluation of Dobson's work and his place in British art history. He is now widely recognized as a painter of exceptional talent and originality, arguably the most distinguished native-born English painter of the 17th century until the advent of William Hogarth nearly a century later. His contemporary, the diarist John Evelyn, praised him, and John Aubrey later referred to him as "the most excellent painter that England hath yet bred."

Modern scholarship has highlighted Dobson's unique contribution: his robust and psychologically penetrating portraiture, his innovative use of allegory, and his ability to capture the sombre mood of Civil War England. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as one held at the National Portrait Gallery in London and another at Oxford University in 2015, have brought his paintings to a wider audience and solidified his reputation. These exhibitions have also helped in attributing more works to him through stylistic analysis and documentary research, as some of his paintings had been misattributed over the centuries.

Dobson's art provides an invaluable visual record of the personalities who shaped one of the most dramatic periods in English history. His portraits of cavaliers, with their blend of defiance and melancholy, offer a powerful counterpoint to the more elegant and courtly images of Van Dyck. He demonstrated that a native English artist could not only master the prevailing European styles but also adapt them to express a distinctly national character and experience.

Dobson in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate William Dobson's achievement, it is essential to view him within the broader artistic context of his time, both in England and on the Continent. His primary artistic dialogue was, of course, with Sir Anthony van Dyck. Van Dyck, a pupil of the great Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, had set an almost impossibly high standard for portraiture in England. Dobson absorbed Van Dyck's lessons in aristocratic presentation but infused them with a more direct, less idealized approach.

His early training under William Peake and later with Francis Cleyn exposed him to different facets of the London art world. Cleyn, with his Continental background, likely reinforced Dobson's understanding of Baroque design principles. The Venetian painters, particularly Titian and Tintoretto, were profound influences, evident in Dobson's rich colourism and dramatic use of light. His contemporary moniker, the "English Tintoretto," speaks to this perceived affinity.

In England, other portraitists were active, though few matched Dobson's power during his peak Oxford years. Cornelius Johnson (Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen), of Dutch extraction, produced sensitive and refined portraits, but his style was generally more reserved than Dobson's. Daniel Mytens, Van Dyck's predecessor as court painter, had already left England by the time Dobson rose to prominence. After Dobson's death and the Restoration, Sir Peter Lely would dominate English portraiture, followed by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Both were foreign-born artists who adapted the Baroque style to English tastes.

Looking across the Channel, the giants of European Baroque were Dobson's contemporaries. In the Dutch Republic, Rembrandt van Rijn was creating his deeply introspective portraits and biblical scenes, while Frans Hals captured the lively burghers of Haarlem. In Spain, Diego Velázquez was the preeminent court painter, producing works of profound dignity and psychological depth. While direct influence from these masters on Dobson is unlikely, they represent the high artistic standards of the era in which he worked.

Dobson's significance lies in his emergence as a strong native talent in a field largely dominated by foreign artists. He paved the way for later generations of British painters, such as William Hogarth, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Thomas Gainsborough, who would go on to establish a celebrated national school of painting.

The Enduring Brushstroke

William Dobson's career was a brief, intense flame lit amidst the storm of civil war. In just a few short years, he produced a body of work that stands as a powerful testament to his talent and to the indomitable spirit of his sitters. His portraits are more than mere likenesses; they are historical documents, psychological studies, and compelling works of art that capture the gravity and heroism of a pivotal moment in English history.

Though his life was cut short by tragedy and his work subsequently overlooked for a period, modern art history has rightfully restored William Dobson to his place as a key figure in the British artistic canon. He remains a compelling example of an artist whose vision was forged in the crucible of conflict, leaving behind images that continue to resonate with their strength, honesty, and profound humanity. His legacy is that of England's first great native painter, a cavalier brush that eloquently chronicled an age of profound upheaval. The auction market has also begun to reflect this renewed appreciation, with works attributed to him, such as a "Portrait of a Gentleman" sold at Christie's in July 2018 for £5,760 (including commission), contributing to a sale that saw significant prices for Old Masters and set a new auction record for a work by the artist, indicating growing collector interest.