Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez stands as one of the towering figures of Western art, the leading painter of the Spanish Golden Age, and a master whose influence resonates through centuries. Born in Seville, the vibrant cultural and economic heart of Spain at the time, around June 6, 1599, Velázquez navigated the complex worlds of artistic apprenticeship, courtly life, and profound artistic innovation until his death in Madrid on August 6, 1660. His work, characterized by stunning realism, psychological depth, and technical brilliance, offers a unique window into the Spain of Philip IV, capturing both the grandeur of the court and the quiet dignity of ordinary life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Seville

Velázquez was baptized on June 6, 1599, suggesting a birth shortly before that date. He hailed from Seville, Andalusia. His family background has been subject to some historical discussion; his paternal grandparents were likely of Portuguese origin, possibly minor nobility, while his mother, Jerónima Velázquez, belonged to the hidalgo class, the lower nobility of Seville. Some accounts suggest a more modest background, even mentioning a shoemaker ancestor, highlighting the fluidity and occasional obscurity of lineage records from the period. Regardless of precise noble connections, the family appears to have been respectably established.

Showing artistic promise early on, Velázquez's formal training began around the age of ten or eleven. He initially spent a brief, reportedly unsatisfactory, period in the workshop of Francisco de Herrera the Elder, a painter known for his vigorous style. By 1611, Velázquez had moved to the studio of Francisco Pacheco, a far more influential figure in his development. Pacheco was not only a painter, albeit of a more conservative, Mannerist-influenced style, but also a respected scholar, art theorist, and writer, whose connections within Seville's intellectual and religious circles were significant.

Pacheco's studio provided Velázquez with a solid grounding in technique, composition, and the humanist ideals that informed much Renaissance and Baroque art. Pacheco recognized his pupil's exceptional talent. The relationship deepened, and in 1618, Velázquez married Pacheco's daughter, Juana. This union further solidified his position within Seville's artistic community. Pacheco would later write an important treatise, Arte de la Pintura (Art of Painting), which provides valuable insights into Velázquez's early career and artistic philosophy.

During his Seville period (roughly until 1622), Velázquez developed a distinct style heavily indebted to the naturalism sweeping across Europe, largely inspired by the Italian master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Caravaggio's dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) and his unidealized depiction of religious and everyday figures found fertile ground in Seville. Velázquez adopted this tenebrism, using focused light sources to model forms and create intense, atmospheric scenes.

His early works often fall into the category of bodegones, genre scenes featuring kitchen settings, food, and ordinary people. Paintings like Old Woman Frying Eggs (c. 1618) and The Waterseller of Seville (c. 1620) exemplify this phase. They showcase his remarkable ability to render textures – pottery, glass, cloth, skin – with uncanny realism and to capture the quiet dignity of his subjects. These works moved beyond simple genre depiction, often imbued with a sense of gravity and psychological presence. He also painted religious subjects during this time, such as The Adoration of the Magi (1619), often placing sacred figures in contemporary settings and attire.

Arrival at the Court of Philip IV

Velázquez's ambition extended beyond Seville. Encouraged by Pacheco and seeking greater opportunities, he made his first trip to Madrid in 1622. While he didn't immediately secure a royal commission, he painted a portrait of the influential poet Luis de Góngora y Argote, showcasing his skill. More importantly, this trip allowed him to see the royal collections, rich in works by Italian Renaissance masters, particularly Titian, whose painterly approach would profoundly influence Velázquez later.

His breakthrough came the following year. Through the connections of his Sevillian network, particularly Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, the powerful chief minister to the young King Philip IV, Velázquez was recalled to Madrid in 1623. He painted a portrait of the King that immediately impressed Philip IV and Olivares. The King reportedly declared that no one else would paint his portrait henceforth. This marked the beginning of Velázquez's lifelong association with the Spanish court.

He was appointed a court painter, receiving a salary, lodgings, and the prestige associated with royal service. This position provided financial security but also placed demands on his time, requiring him to produce numerous portraits of the royal family and members of the court. His early Madrid portraits, while retaining some of the sharp realism of his Seville period, began to show a slightly more formal quality appropriate for royal subjects. He quickly outshone the established court painters like Vicente Carducho and Eugenio Cajés.

The Influence of Rubens and the First Italian Journey

A pivotal moment occurred in 1628 with the arrival of Peter Paul Rubens in Madrid on a diplomatic mission. Rubens, the preeminent Baroque painter of Northern Europe, spent nine months at the Spanish court. Velázquez had the unique opportunity to interact closely with the celebrated Flemish master, observing his working methods and discussing art. Rubens, known for his dynamic compositions, rich color, and fluid brushwork, held Velázquez's talent in high regard and encouraged his artistic development.

Rubens' presence and his admiration for the Italian masters, particularly Titian, likely reinforced Velázquez's desire to study art in Italy firsthand. With the King's permission and financial support, Velázquez embarked on his first Italian journey in August 1629, remaining there until early 1631. This trip was crucial for broadening his artistic horizons.

He traveled extensively, visiting Genoa, Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples. In Venice, he studied the works of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, absorbing their mastery of color, light, and composition. In Rome, he encountered classical sculpture and the masterpieces of Raphael and Michelangelo, as well as the continuing influence of Caravaggio and the works of contemporary Baroque artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona. In Naples, he likely met fellow Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera, another follower of Caravaggio known for his intense realism.

During this trip, Velázquez produced several important works, including Joseph's Bloody Coat Presented to Jacob and Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (both c. 1630). These paintings demonstrate a brighter palette, more complex multi-figure compositions, and a greater command of human anatomy and expression compared to his earlier works. They show him assimilating Italian influences while retaining his own distinct artistic personality. The trip fundamentally transformed his style, moving him towards a more painterly approach with looser brushwork and a greater emphasis on capturing light and atmosphere.

Return to Madrid and Mature Portraiture

Upon his return to Madrid in 1631, Velázquez resumed his duties as court painter with enhanced prestige and a refined artistic vision. The following two decades marked the height of his career, during which he produced many of his most celebrated portraits and historical paintings. His style continued to evolve, characterized by increasingly free and economical brushwork, a subtle and sophisticated use of color (often relying on a limited palette of blacks, grays, silvers, ochres, and reds), and an unparalleled ability to capture the essence of his sitters.

He painted numerous portraits of Philip IV throughout the King's reign, documenting the monarch's aging process with unflinching honesty yet always maintaining royal decorum. Portraits like Philip IV in Brown and Silver (c. 1632) show a new elegance and mastery of texture. He also painted the powerful Count-Duke of Olivares, capturing his imposing presence, and the young heir to the throne, Infante Baltasar Carlos, often depicted on horseback or in hunting attire, symbolizing youthful energy and royal lineage (Prince Baltasar Carlos on Horseback, c. 1635).

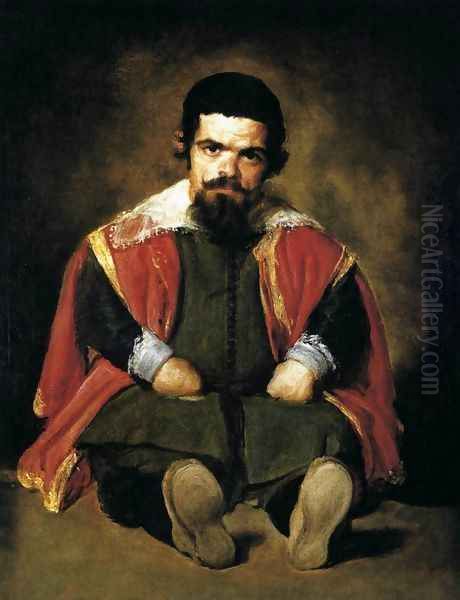

Velázquez's portraits were not limited to the highest echelons of the royal family. He painted court officials, intellectuals, and notably, the court jesters and dwarfs (bufones). These portraits, such as those of Sebastián de Morra (c. 1645) and Francisco Lezcano ("El Niño de Vallecas") (c. 1643-45), are remarkable for their empathetic and dignified portrayal of individuals often marginalized by society. Velázquez depicted them with the same psychological insight and technical brilliance as his royal sitters, revealing their humanity beyond their court roles.

Religious, Mythological, and Historical Works

While portraiture dominated his output due to his court position, Velázquez also tackled other genres. His religious paintings, though relatively few compared to other Spanish Baroque artists like Francisco de Zurbarán or Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, are distinctive. Works like Christ Crucified (c. 1632) are characterized by their serene classicism, quiet intensity, and focus on the human aspect of the divine, often avoiding the overt emotionalism or graphic depictions of suffering common in Spanish religious art. He drew inspiration from Pacheco's iconographic guidelines but infused the subjects with his own restrained naturalism.

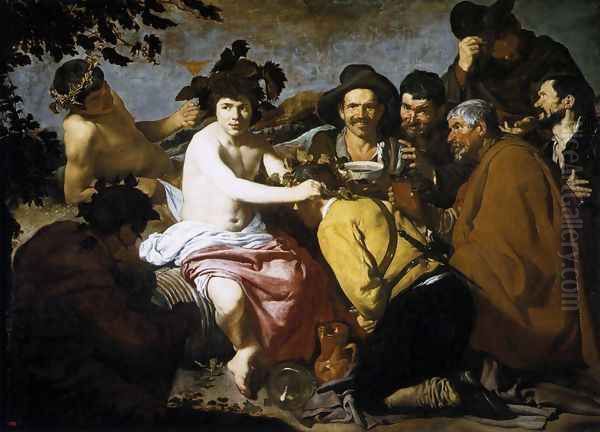

His mythological paintings, such as The Triumph of Bacchus (also known as Los Borrachos or The Drinkers, c. 1629) and the later Rokeby Venus (c. 1647-51), also demonstrate his unique approach. Los Borrachos depicts the god Bacchus mingling with Spanish peasants, grounding the classical myth in contemporary reality with remarkable realism. The Rokeby Venus, his only surviving female nude, is a masterpiece of sensuousness and technical skill, notable for its naturalistic depiction and the intriguing use of a mirror, a device he would later employ famously in Las Meninas.

Perhaps his greatest achievement outside of portraiture is the historical painting The Surrender of Breda (also known as Las Lanzas, c. 1634-35). Commissioned for the Hall of Realms in Philip IV's Buen Retiro Palace, it depicts a moment from the Eighty Years' War, the handover of the keys of the Dutch city of Breda to the Spanish general Ambrogio Spinola. Velázquez transcends mere reportage, creating a complex composition that emphasizes magnanimity and reconciliation rather than triumphalism. The painting is celebrated for its masterful handling of figures, landscape, light, and atmosphere, capturing a specific historical event with profound human insight.

The Second Italian Journey and Papal Portrait

Velázquez undertook a second journey to Italy from late 1648 or early 1649 to mid-1651. This trip had a dual purpose: to acquire paintings and classical sculptures for the King to decorate the newly refurbished Alcázar palace in Madrid, and to further his own artistic development. He spent most of his time in Rome, where his fame preceded him.

During this stay, he painted several portraits, including one of his assistant, Juan de Pareja (1650). Pareja, of Moorish descent, was Velázquez's enslaved assistant who later became an independent painter after Velázquez freed him in Rome. The portrait of Pareja, exhibited publicly, caused a sensation and earned Velázquez admission into prestigious Roman artistic societies, including the Academy of Saint Luke.

The crowning achievement of this second Italian trip was the Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650). Considered one of the greatest portraits in the history of art, it is a stunningly realistic and psychologically penetrating depiction of the powerful pontiff. Velázquez captured the Pope's shrewd intelligence and formidable personality with an economy of means, using bold brushwork and a restricted palette dominated by reds and whites. The painting was highly acclaimed in Rome and cemented Velázquez's international reputation. Francis Bacon, centuries later, would become obsessed with this portrait, creating numerous variations.

Late Career and Court Duties

Returning to Spain in 1651, Velázquez entered the final phase of his career. In 1652, he was appointed Aposentador Mayor de Palacio (Grand Marshal of the Palace or Usher of the Chamber), a high-ranking and demanding administrative position that involved overseeing the royal household's quarters, organizing ceremonies, and managing decorations. While this role brought great honor and proximity to the King, it significantly reduced the time he could dedicate to painting.

Despite these duties, his artistic output in the 1650s includes some of his most profound and enigmatic works. His technique became even freer and more abbreviated, relying on suggestion and the viewer's perception to complete the image. He achieved an astonishing mastery of light and atmosphere, creating effects that anticipated Impressionism centuries later.

Las Meninas: A Masterpiece of Complexity

Painted in 1656, Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour) is widely regarded as Velázquez's supreme masterpiece and one of the most complex and debated paintings in Western art history. It depicts a seemingly informal scene in a large room in the Madrid Alcázar. The central figure is the young Infanta Margarita Teresa, attended by her maids of honour (meninas), dwarfs (Mari Bárbola and Nicolasito Pertusato), and a large dog.

Velázquez himself is prominently featured on the left, standing before a large canvas, palette and brush in hand, looking out towards the viewer. In the background, reflected in a mirror on the far wall, are the figures of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana, suggesting they are positioned where the viewer stands, observing the scene or perhaps being painted by Velázquez. Another courtier, José Nieto Velázquez (possibly a relative of the painter), is silhouetted in a doorway at the back, adding another layer of spatial depth and ambiguity.

Las Meninas is a technical tour de force in its handling of light, space, and perspective. The complex interplay of gazes between the figures, the viewer, the painter, and the reflected royal couple creates a web of relationships that challenges traditional notions of representation. The painting raises questions about reality and illusion, the relationship between the artist and his patrons, and the status of painting itself.

The prominent inclusion of Velázquez, wearing the keys of his palace office and later (reportedly added after his death, possibly by the King's order) the red cross of the prestigious Order of Santiago on his chest, can be interpreted as an assertion of the nobility of painting and the high status achieved by the artist within the court. The painting's intricate structure, masterful execution, and layers of meaning have fascinated artists and critics for generations, inspiring interpretations by figures like Luca Giordano, Goya, Manet, Picasso (who painted a series of variations), and Michel Foucault.

Late Works

Among Velázquez's other significant late works is Las Hilanderas (The Spinners), also known as The Fable of Arachne (c. 1657). Ostensibly a genre scene depicting women working in the royal tapestry factory of Santa Isabel in Madrid, it incorporates a mythological scene in the brightly lit background: the contest between the mortal weaver Arachne and the goddess Minerva, based on Ovid's Metamorphoses. The painting is celebrated for its dynamic composition, the illusion of movement (particularly the spinning wheel), and its complex layering of reality and myth, manual labor and high art.

His late portraits, such as those of the Infanta Margarita Teresa (who was the subject of several paintings as she grew older, destined for potential suitors abroad), continue to showcase his evolving style. The brushwork becomes almost impressionistic, capturing fleeting moments and the play of light on surfaces with remarkable fluidity and economy.

Technique and Style Evolution

Velázquez's technique evolved significantly throughout his career but was consistently grounded in keen observation and a commitment to realism. Key elements include:

Naturalism: A foundation laid in Seville under the influence of Caravaggio, focusing on depicting subjects truthfully, without excessive idealization.

Chiaroscuro: Early mastery of strong light-dark contrasts for dramatic effect and modeling form.

Alla Prima: Often painting directly onto the canvas with minimal underdrawing, especially in later works, giving his paintings a sense of immediacy and freshness.

Loose Brushwork: Increasingly free and visible brushstrokes in his mature and late periods. From a distance, these strokes coalesce into convincing representations of form, texture, and light. This technique, known as borrones (blots or stains), was revolutionary for its time.

Limited Palette: Often achieving rich effects with a surprisingly restricted range of colors, masterfully manipulating tones and values, particularly with blacks, grays, and ochres.

Mastery of Light and Atmosphere: An unparalleled ability to capture the subtle effects of light and air, creating a sense of space and presence often referred to as the "aer vagante" (wandering air).

Psychological Insight: A profound capacity to convey the inner life and character of his sitters, whether king, pope, jester, or artisan.

Some scholars have speculated about Velázquez's possible use of optical devices like mirrors or a camera obscura to achieve his remarkable realism, particularly in complex compositions like Las Meninas. While there's no definitive proof, his intense focus on visual accuracy and optical effects aligns with the scientific interests of the Baroque era. His exploration of transparent glazes also contributed to the luminosity and depth of his later works.

Velázquez and His Contemporaries

Velázquez operated within a rich artistic context. His teacher and father-in-law, Francisco Pacheco, provided his initial training and intellectual grounding. The encounter with Peter Paul Rubens was pivotal, encouraging his Italian studies and potentially influencing his appreciation for painterly techniques.

In Italy, he absorbed lessons from Renaissance giants like Titian, Tintoretto, and Raphael, as well as the Baroque naturalism of Caravaggio and his followers, including fellow Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera. He would have been aware of the work of major Italian Baroque figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Annibale Carracci.

Within Spain, his contemporaries included masters like Francisco de Zurbarán, known for his austere religious paintings and still lifes; Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, famed for his sentimental religious images and genre scenes; and Alonso Cano, a sculptor, architect, and painter. While Velázquez's court position set him somewhat apart, these artists collectively defined the Spanish Golden Age of painting.

His relationship with Juan de Pareja is particularly interesting – moving from an enslaved assistant to a freedman and independent artist, Pareja's own work shows Velázquez's influence.

Comparisons are often made with his great Northern European contemporary, Rembrandt van Rijn. Both were masters of realism, psychological portraiture, and the expressive use of light and shadow within the Baroque framework. However, they pursued different paths: Velázquez achieved high courtly status and developed a cool, objective yet deeply insightful style, while Rembrandt faced financial hardship later in life and explored a more personal, emotionally charged realism. There is no evidence of direct contact or influence between them during their lifetimes, but they represent parallel peaks of 17th-century painting.

Legacy and Influence

Velázquez's influence during his lifetime was primarily felt within Spain. After his death, his reputation somewhat faded outside the court until the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The opening of the Museo del Prado in Madrid in 1819, housing the bulk of the Spanish royal collection including numerous Velázquez masterpieces, was crucial in re-establishing his international fame.

His work profoundly impacted later artists. Francisco Goya revered him, studying and creating etchings after his paintings. In the 19th century, Realist and Impressionist painters, particularly in France, rediscovered Velázquez. Édouard Manet famously called him the "painter of painters" and traveled to Madrid to study his works, which directly influenced Manet's own style, particularly his use of black and his direct, unidealized approach to subjects. James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent also drew heavily on Velázquez's portraiture techniques and tonal harmonies.

In the 20th century, artists continued to engage with Velázquez. Pablo Picasso's extensive series of variations on Las Meninas (1957) is a testament to the painting's enduring power. Salvador Dalí also paid homage to Velázquez in various works. Francis Bacon's haunting series based on the Portrait of Pope Innocent X explored the psychological intensity of Velázquez's image.

Velázquez's legacy lies in his extraordinary technical skill, his profound humanism, his innovations in realism and painterly technique, and his creation of some of the most compelling and enigmatic images in art history. He elevated portraiture to a high art form and captured the spirit of his age with unparalleled clarity and depth.

Personal Life and Unanswered Questions

Despite his fame, details about Velázquez's personal life remain relatively scarce. He married Juana Pacheco in 1618, and they had two daughters, Francisca and Ignacia. Only Francisca survived infancy; she later married Velázquez's pupil, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, who also became a court painter.

Velázquez seems to have been a reserved and dignified individual, dedicated to his art and his position at court. His inventory, taken after his death, reveals a substantial library with books on art theory, mathematics, astronomy, history, and poetry, indicating broad intellectual interests. The management of his estate by Pacheco and his friend Gaspar de Fuensalida provides some administrative details.

Some mysteries persist. The precise nature of his family's noble status remains debated. His reasons for apparently not joining religious confraternities or signing certain types of contracts, unlike many contemporaries, are unclear. While he achieved the coveted Order of Santiago shortly before his death – a significant honor requiring proof of "purity of blood" (no Jewish or Moorish ancestry) – the process was lengthy and complex, reflecting the rigid social structures of the time.

Conclusion

Diego Velázquez occupies a unique and pivotal position in the history of art. As the leading painter at the court of Philip IV, he created an enduring record of the Spanish monarchy and its world during the Golden Age. His commitment to realism, combined with an increasingly sophisticated and economical technique, allowed him to capture both the outward appearance and the inner psychology of his subjects with profound insight. From the humble bodegones of his youth to the dazzling complexity of Las Meninas, his work consistently demonstrates technical mastery and intellectual depth. He absorbed the lessons of his predecessors, particularly Caravaggio and Titian, and forged a style entirely his own, one that looked forward to modern painting in its emphasis on light, atmosphere, and the act of seeing itself. Velázquez remains a "painter of painters," an artist whose work continues to challenge, inspire, and captivate viewers centuries after his death.