William Henry Hamilton Trood stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Victorian art, particularly celebrated for his exceptional ability to capture the character and spirit of dogs. In an era captivated by animal companionship and the burgeoning culture of dog fancying, Trood's work found a receptive audience, offering detailed, sympathetic, and often charming portrayals of man's best friend. His paintings, while focused on a specific niche, reflect the broader artistic currents and societal values of 19th-century Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1848 in Taunton, Somerset, England, William Henry Hamilton Trood (often cited as W. H. H. Trood) displayed an affinity for art, and specifically for depicting animals, from a remarkably young age. Sources suggest he began sketching and observing dogs as early as four years old. This early fascination was not a fleeting childhood interest but the foundation of a lifelong passion and professional pursuit. Unlike many artists of his time who underwent formal academic training in prestigious art schools from their youth, Trood appears to have been largely self-taught in his formative years, honing his skills through direct observation and relentless practice.

He reportedly felt that he did not produce truly satisfactory dog paintings until he was around twenty years old, a testament to his own high standards and the dedication required to master the complex anatomy, varied expressions, and dynamic postures of his canine subjects. This period of intense self-study allowed him to develop an intimate understanding of animal behavior, which would become a hallmark of his mature work. His sister, Mabel Grace Trood, also pursued a career as a painter, suggesting a familial environment that may have nurtured artistic talent.

The Victorian Context: A Passion for Animals and Art

To fully appreciate Trood's contribution, it is essential to understand the Victorian era's unique relationship with animals, particularly dogs. The 19th century saw an unprecedented rise in pet ownership, the formalization of dog breeds, and the establishment of kennel clubs and dog shows. Queen Victoria herself was an avid dog lover and owner, setting a trend that permeated society. This cultural shift created a fertile market for animal portraiture.

Artists like Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) had already elevated animal painting to a high art form, imbuing his subjects with human-like emotions and often placing them in narrative or allegorical contexts. Landseer's immense popularity set a precedent, and while Trood's work shares a deep affection for animals, his approach often differed in its subtlety and focus. Other notable animal painters of the period or those whose influence might have been felt include Briton Rivière (1840-1920), known for his dramatic scenes often featuring animals and humans, and John Emms (1843-1912), who specialized in hounds and terriers with a vigorous, painterly style. The tradition of British animal painting also looked back to figures like George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose anatomical precision set a standard, and George Morland (1763-1804), known for his rustic scenes often including animals.

Trood's Artistic Development and Style

Trood's artistic career gained public visibility from 1879 when he began exhibiting his works. He became a regular contributor to prestigious venues, most notably the Royal Academy in London, where he showed his paintings almost annually until 1898, the year before his death. He also exhibited at other significant institutions such as the Royal Society of British Artists (Suffolk Street), the New Watercolour Society, and the Grosvenor Gallery. This consistent presence in major exhibitions indicates a respected position within the London art world.

His style is characterized by a high degree of finish, meticulous attention to detail, and a profound sympathy for his subjects. Trood possessed an uncanny ability to capture the individual personality of each dog, from the texture of its fur and the gleam in its eye to its characteristic pose and expression. While his paintings are undeniably charming and often evoke a sense of warmth, they generally avoid the overt sentimentality that could sometimes be found in Victorian art. He aimed for a truthful representation, informed by his deep understanding of canine anatomy and behavior. This sets him apart from artists who might overly anthropomorphize their subjects, though his titles often hinted at human-like scenarios or emotions.

His technique involved careful layering of paint to achieve realistic textures, whether the smooth coat of a greyhound or the rough fur of a terrier. His compositions were often intimate, focusing on one or a few animals in domestic or kennel settings, allowing the viewer to connect directly with the subjects. This contrasts with the grander, often more dramatic, compositions of some contemporaries like Richard Ansdell (1815-1885), who frequently depicted sporting scenes or pastoral landscapes with animals.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Several of Trood's paintings have become particularly well-known and exemplify his artistic strengths. Titles often played a significant role, guiding the viewer's interpretation and adding a narrative or emotional layer to the visual depiction.

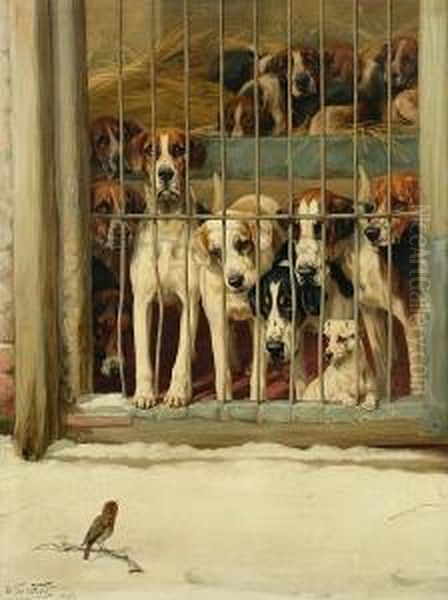

One of his most famous and highly valued works is often referred to as "Hounds in a Kennel" or "Dogs in Show." This painting, showcasing a group of hounds in a kennel environment, demonstrates his skill in depicting multiple animals, each with its own distinct character, within a cohesive composition. The attention to the varied breeds, their interactions, and the textures of their coats and surroundings is remarkable. Such a piece would have appealed greatly to the sporting gentry and dog enthusiasts of the time.

Other works carry titles that suggest charming, everyday scenarios, often with a touch of humor or gentle pathos:

"A Coveted Bone": This likely depicted a common canine scenario, allowing Trood to explore expressions of desire, possession, or playful rivalry.

"Now I Feel Better": Such a title implies a narrative of a dog recovering from a minor ailment or discomfort, showcasing Trood's ability to convey subtle emotional states.

"Dinner Time—Very Hungry": This theme provided an opportunity to depict eager anticipation and the lively energy of dogs awaiting a meal.

"Sweet Home": This title suggests a scene of domestic comfort and contentment, reflecting the Victorian ideal of the home and the cherished place of pets within it.

"The Old Man's Darling": This work likely portrayed an intimate bond between an elderly owner and a beloved canine companion, a theme with universal appeal.

These titles, while anthropomorphic, served to make the paintings more accessible and relatable to a broad audience. They tapped into the Victorian fondness for narrative and sentiment, but Trood's execution remained grounded in realistic observation. His focus was less on grand allegories, like those sometimes explored by artists such as George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) in his symbolic works (though Watts was not primarily an animal painter), and more on the lived experience and inherent appeal of the animals themselves.

Anecdotes and Artistic Process

Trood's dedication to his craft extended to some rather unconventional methods. It is famously recounted that he once attempted to hypnotize his own dogs to keep them still for painting. The experiment was reportedly unsuccessful, as he found that the dogs' eyes took on an unnatural, glazed appearance under hypnosis, which was antithetical to his goal of capturing their lively, expressive gazes. This anecdote, while amusing, highlights his commitment to achieving lifelike representations and his willingness to experiment, even if those experiments did not always yield the desired results.

He was also known to keep a variety of animals in his Chelsea home and garden, including foxes, badgers, and otters, in addition to his beloved dogs. These animals were said to have had the run of his studio at times. This close, daily proximity to a range of creatures undoubtedly deepened his understanding of animal anatomy, movement, and behavior, enriching the authenticity of his paintings. This practice of keeping animal models close at hand was not unique; Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), the celebrated French animal painter, famously maintained a menagerie for study.

Comparisons with Contemporaries and Influences

While Trood carved out his own niche, his work can be situated within the broader context of 19th-century animal painting. He shared with John Sargent Noble (1848-1896) a focus on dogs, particularly sporting breeds, though Noble's style could be somewhat broader. Maud Earl (1864-1943), a slightly younger contemporary, also gained fame for her dog portraits, often working on commission for wealthy patrons and capturing specific breeds with great fidelity, much like Trood.

The influence of earlier masters of animal art, such as the aforementioned George Stubbs, with his scientific approach to anatomy, and the Dutch Golden Age painters like Paulus Potter (1625-1654), known for his detailed depictions of livestock in landscapes, formed a backdrop to the entire genre. While Trood's work was distinctly Victorian in its sentiment and finish, the underlying principles of careful observation and anatomical accuracy connect him to this longer tradition.

His dedication to realism, albeit a sympathetic realism, aligns with broader trends in Victorian art, which saw a move away from the idealization of earlier periods towards a greater emphasis on verisimilitude, partly influenced by the advent of photography. However, unlike the sometimes stark social realism of artists like Luke Fildes (1843-1927) or Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914) when depicting human subjects, Trood's realism was tempered by affection for his animal subjects.

Later Life and Legacy

William Henry Hamilton Trood continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1880s and 1890s, maintaining a consistent output of high-quality animal portraits. His works were popular and sold well, finding homes in the collections of dog enthusiasts and art lovers alike. He resided in Chelsea for a significant part of his career, a popular London district for artists, before moving to Taunton in Somerset, where he passed away prematurely on November 2nd, 1899, at the age of 51 (though some sources state 1860 as his birth year, making him 39, the 1848 birth year is more commonly accepted by art historical resources, making him 51).

Despite his contemporary success, Trood, like many specialized Victorian painters, experienced a period where his work was somewhat overshadowed by the rise of modern art movements in the early 20th century. However, in more recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for Victorian art in all its diversity, and artists like Trood have been reassessed. His paintings are now sought after by collectors, and his name is firmly established among the notable animal painters of his era.

His legacy lies in his sensitive and skillful portrayal of dogs, capturing not just their physical likeness but also their individual characters. He contributed significantly to a genre that held a special place in the hearts of the Victorians and continues to resonate with animal lovers today. His work serves as a charming visual record of the breeds popular in his time and the deep affection humans have long held for their canine companions. He stands alongside artists like Wright Barker (1864-1941), who also specialized in animal and sporting scenes, and Heywood Hardy (1842-1933), known for his elegant depictions of animals in 18th-century settings, as a dedicated practitioner of animal art.

Conclusion

William Henry Hamilton Trood was more than just a painter of dogs; he was a keen observer of animal nature, a skilled technician, and an artist who understood the emotional connection between humans and animals. His career coincided with a peak in the popularity of his chosen subject, and he met the demand with works of enduring quality and appeal. From his early, self-directed studies to his consistent presence at the Royal Academy, Trood demonstrated a lifelong dedication to his art. His paintings, characterized by their meticulous detail, sympathetic portrayal, and avoidance of excessive sentimentality, offer a delightful window into the Victorian world and its love affair with dogs. While he may not have sought the grand historical themes of some of his peers, his focused dedication to capturing the essence of his canine subjects has ensured his lasting place in the annals of British art. His work continues to be admired for its technical skill, its charm, and its heartfelt celebration of the animal kingdom.