Ozias Humphry (1742-1810) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 18th-century British art. A versatile artist, he navigated the demanding world of portraiture with considerable skill, excelling first in the delicate art of miniature painting before transitioning to larger-scale works in oil and pastel. His career spanned a dynamic period in British art, witnessing the towering presence of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, the rise of the Royal Academy of Arts, and the burgeoning interest in exotic locales like India. Humphry's life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic, social, and intellectual currents of his time, marked by ambitious travels, influential friendships, and a dedicated pursuit of his craft despite personal challenges.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Devon

Born in Honiton, Devon, in 1742, Ozias Humphry's early life was rooted in a provincial setting, yet one that was not entirely devoid of artistic stimuli. His father was a peruke-maker and mercer, a respectable trade, but it was the world of images that captivated young Ozias. A pivotal moment in his youth was his exposure to the collection of paintings at the nearby residence of the Duke of Devonshire. This encounter with art, likely featuring works by Old Masters and contemporary painters, ignited a passion that would define his life's path.

Recognizing his burgeoning talent and interest, Humphry was sent to London to further his artistic education. He enrolled at Shipley's Academy, a drawing school established by William Shipley and later run by Henry Pars. This institution was a crucial training ground for many aspiring artists of the period, providing foundational skills in drawing from casts and life. Here, Humphry would have honed his draughtsmanship, an essential skill for any portraitist, particularly one who would later specialize in the exacting detail required for miniatures.

Following his initial training in London, Humphry relocated to Bath around 1760. Bath, at this time, was a fashionable spa town, a hub of social activity for the aristocracy and gentry. This made it a fertile ground for portrait painters, as visitors and residents alike sought to commemorate their likenesses. It was in Bath that Humphry began to establish himself as a miniaturist. He also formed a significant friendship with the artist William Pars, who would later become known for his topographical views and drawings of classical antiquities. This period in Bath was crucial for Humphry, allowing him to develop his skills and build a client base in a less competitive environment than London.

The London Art Scene and Early Success in Miniatures

By 1764, Humphry had moved back to London, ready to make his mark on the capital's vibrant art scene. He took lodgings with the celebrated painter George Romney, an association that would develop into a lifelong friendship and prove influential for both artists. London was the epicenter of British art, dominated by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough. While these titans excelled in large-scale oil portraiture, there was a strong market for portrait miniatures, intimate keepsakes that were highly valued.

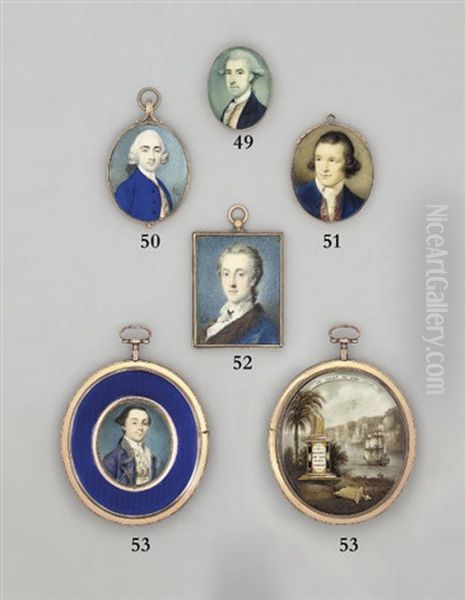

Humphry quickly gained recognition for his exquisite miniatures. His style was characterized by its delicacy, refined draughtsmanship, and a subtle, harmonious use of color. He exhibited regularly at the Society of Artists and later at the Royal Academy of Arts, which was founded in 1768. His sitters included members of the aristocracy, literary figures, and fellow artists. The intimacy of the miniature format suited Humphry's talent for capturing a sitter's likeness with sensitivity and psychological insight. He competed in a field that included other notable miniaturists such as Richard Cosway and John Smart, each with their distinct styles, but Humphry carved out a reputation for elegance and a certain gentle realism.

His success as a miniaturist provided him with a steady income and a growing reputation. However, like many ambitious artists of his era, Humphry aspired to work on a grander scale and to broaden his artistic horizons through direct exposure to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. This ambition, coupled with a period of professional strain, led him to contemplate the traditional rite of passage for an 18th-century artist: the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour: Italy and its Enduring Influence

In the spring of 1773, Ozias Humphry embarked on a journey to Italy, a pivotal experience in his artistic development. He traveled with his close friend, George Romney. For British artists, Italy, particularly Rome, was considered the ultimate schoolroom. It offered the opportunity to study firsthand the sculptures of antiquity, the frescoes of Raphael and Michelangelo, and the paintings of Titian, Correggio, and other Renaissance and Baroque masters.

Upon arriving in Rome, Humphry and Romney immersed themselves in the city's artistic treasures. Humphry attended classes at the French Academy in Rome, a common practice for visiting artists seeking structured study. He diligently copied Old Masters, a traditional method of learning composition, color, and technique. His surviving sketchbooks and letters from this period attest to his assiduous study. He is known to have made copies after Raphael, including studies of figures from the Transfiguration. This direct engagement with Renaissance art undoubtedly refined his understanding of form and composition.

Beyond Rome, Humphry's Italian sojourn included visits to other important artistic centers. He traveled to Naples, where he would have encountered the recently excavated Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and likely met Sir William Hamilton, the British envoy and renowned collector of antiquities. He also visited Florence, with its Uffizi Gallery and Pitti Palace, and Venice, the city of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, where the emphasis on color and light offered a different aesthetic education. His travels extended to Milan before he began his journey back to England.

The Italian experience, which lasted until 1777, had a profound impact on Humphry. While he continued to work in miniatures, his ambitions increasingly turned towards larger formats, particularly oil painting and pastels. The exposure to the grandeur of Italian art likely fueled this desire to work on a more monumental scale.

Return to England and Shifting Artistic Focus

Humphry returned to England in 1777, his artistic vision broadened and his ambitions re-energized. He sought to establish himself as a painter of larger portraits in oil, a more prestigious and potentially more lucrative field than miniatures. However, this transition was not without its challenges. The London art world was highly competitive, with established figures like Reynolds, Gainsborough, and his friend Romney dominating the market for large-scale portraiture.

Despite the competition, Humphry began to exhibit oil paintings and pastels at the Royal Academy. His work in pastels, or "crayons" as they were often called, gained particular notice. This medium, which had been popularized in Britain by artists like Francis Cotes and the Swiss master Jean-Étienne Liotard, allowed for a softness and luminosity that suited Humphry's delicate touch. His pastel portraits were admired for their refined execution and pleasing color harmonies.

A significant factor that influenced Humphry's shift away from miniatures was his deteriorating eyesight. The intense, close work required for miniature painting became increasingly difficult for him. While this was a personal misfortune, it spurred his development in other media. His oil paintings, though perhaps not achieving the same level of widespread acclaim as his miniatures or pastels, demonstrated his competence in composition and characterization. He continued to receive commissions from a distinguished clientele, including members of the royal family and the aristocracy.

The Indian Sojourn: Ambition and Adversity

In 1785, seeking new opportunities and perhaps a more favorable climate for his health and finances, Ozias Humphry embarked on an ambitious voyage to India. This was a bold move, as India was a distant and challenging environment for European artists. However, the subcontinent, with its wealthy Nawabs and British East India Company officials, offered the prospect of lucrative commissions. Artists like Tilly Kettle and Johan Zoffany had already found success painting portraits in India.

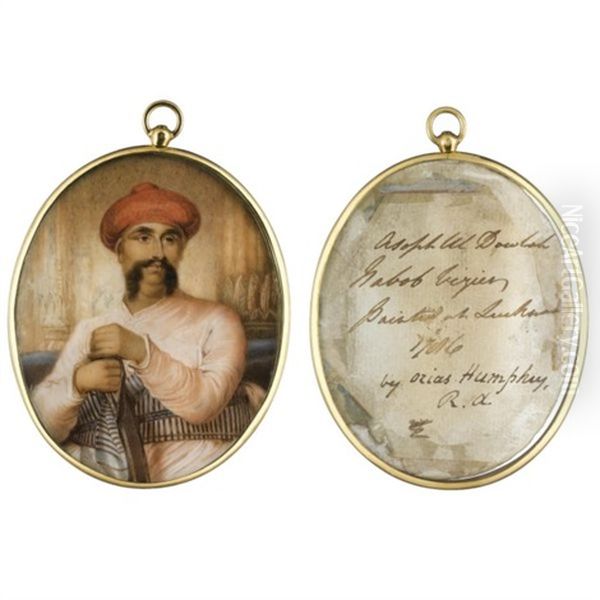

Humphry spent approximately two and a half years in India, primarily in Calcutta, Lucknow, and Benares. He secured patronage from prominent figures, most notably Asaf-ud-Daula, the Nawab Wazir of Oudh. For the Nawab, Humphry painted several portraits, including a notable large-scale oil of the ruler himself and another of his minister, Hyder Beg Khan. These works are valuable historical documents, offering insights into the opulence and personalities of the Indian courts. He also painted miniatures of various Indian nobles and British residents.

Despite some successes, Humphry's Indian venture was not the resounding financial triumph he had hoped for. The climate was harsh, materials were sometimes difficult to obtain, and navigating the complex social and political landscape of colonial India presented its own challenges. Furthermore, his failing eyesight continued to be a concern, making the execution of detailed work increasingly arduous. He returned to England in 1788, his health somewhat impaired and his financial situation not significantly improved. Nevertheless, his Indian works represent a fascinating chapter in his career and contribute to the visual record of British artistic engagement with India.

Later Career, Royal Appointments, and Artistic Style

Back in England, Humphry resumed his career, focusing more on pastels and occasionally oils, as his eyesight made miniature painting largely impossible. His reputation remained solid, and in 1791, he was elected a full member of the Royal Academy of Arts (RA), a significant honor that recognized his standing within the British art community. The following year, in 1792, he received a prestigious royal appointment as Portrait Painter in Crayons to King George III. This was a testament to his skill in the pastel medium and his connections within courtly circles.

Humphry's artistic style, across all media, was characterized by a refined sensibility. His miniatures, as previously noted, were celebrated for their delicacy, precision, and subtle coloration. He often used a stippling technique to achieve smooth transitions of tone, and his likenesses were generally considered faithful and imbued with a gentle charm. His ivory surfaces glowed with a soft luminosity.

In his pastels, Humphry demonstrated a masterful command of the medium. He achieved a remarkable softness and richness of color, often employing a harmonious palette of blues, pinks, and creams. His pastel portraits, like Charlotte, Princess Royal, possess an elegance and an airy quality that was highly fashionable. He was adept at rendering the textures of fabrics – silks, satins, and lace – and capturing the subtle nuances of flesh tones. His preference for softer, more blended effects in pastel distinguished his work from the more robust, linear style of some of his contemporaries.

His oil paintings, while perhaps less consistently successful than his work in other media, still displayed his strong draughtsmanship and compositional skills. Works like his portrait of Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab of Oudh show an ability to handle larger compositions and convey a sense of dignity and presence. However, it is generally acknowledged that his greatest strengths lay in the more intimate formats of miniature and pastel, where his delicate touch and refined color sense could be fully expressed.

Key Relationships and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Ozias Humphry cultivated and maintained several important relationships within the artistic and literary worlds. His long-standing friendship with George Romney was undoubtedly one of the most significant. Their shared experiences on the Grand Tour and their mutual support in London's competitive art scene underscore a deep personal and professional bond.

Another crucial, and perhaps more unexpected, connection was with the visionary poet and artist William Blake. Humphry was an early and important patron of Blake. He commissioned Blake to produce illuminated copies of his prophetic books, including America a Prophecy and Europe a Prophecy. Humphry also commissioned Blake to create a series of tempera paintings, "The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan" and "The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth," though these were later. This patronage was vital for Blake, who often struggled for recognition and financial stability. Humphry's appreciation for Blake's unique genius, at a time when many found his work perplexing, speaks to Humphry's own breadth of artistic understanding. He also employed Blake to make miniature copies of some of his own larger portraits, a practical arrangement that benefited both artists. It is through Humphry's commission that we have Blake's remarkable illustrations to Gray's poems.

Humphry was also acquainted with Sir Joshua Reynolds, the dominant figure in British art. As a member of the Royal Academy, Humphry would have interacted with Reynolds and other leading academicians like Benjamin West, who succeeded Reynolds as President, and Angelica Kauffman, one of the few female founding members. He also knew the animal painter George Stubbs well. In fact, Humphry's manuscript notes, based on conversations with Stubbs, became a primary source for later biographies of the artist, preserving valuable information about Stubbs's life and working methods.

His circle extended to literary figures as well. He was commissioned by the Shakespearean scholar Edmond Malone to make a drawing of the Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, a task that placed him at the intersection of art and literary history. These connections highlight Humphry's integration into the cultural life of Georgian England.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Ozias Humphry's oeuvre, representing different phases of his career and his mastery of various media.

Among his Indian period works, the portraits of Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab of Oudh and his minister Hyder Beg Khan are particularly significant. These paintings, executed in oil, capture the grandeur of the Indian court and provide valuable visual records of these powerful figures. They also reflect the cross-cultural encounters that characterized the British presence in India.

His pastel portrait of Charlotte, Princess Royal, later Queen of Württemberg (circa 1790s), showcases his skill as Portrait Painter in Crayons to the King. The work is notable for its delicate handling, soft colors, and the elegant portrayal of the young princess. It exemplifies the refined aesthetic that made his pastels so popular.

An earlier miniature, perhaps of A Young Gentleman (circa 1770s), would demonstrate the exquisite detail and psychological sensitivity that characterized his best work in this medium. These small, jewel-like objects were personal and intimate, and Humphry excelled at conveying character within their confined dimensions.

His portrait of Suliman Aga, le Bey de Libye (Suliman Aga, the Tripolitan Ambassador), exhibited in 1770, was an early success that demonstrated his ability to capture exotic subjects with dignity and precision, a skill that would later serve him well in India.

The aforementioned sketch of the Chandos Portrait of Shakespeare for Edmond Malone, though a copy, is significant for its role in the ongoing study and iconography of England's greatest playwright. It underscores Humphry's reputation as a skilled and reliable draughtsman.

His relationship with William Blake also led to Humphry owning or commissioning unique items, such as Blake's hand-colored copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, further cementing Humphry's role as a discerning patron of one of Britain's most original artists.

Challenges, Personality, and Later Life

Ozias Humphry's career was not without its difficulties. The most significant personal challenge was his progressively failing eyesight, which began to trouble him relatively early in his career and ultimately forced him to abandon miniature painting, his first and perhaps greatest strength. This adversity, however, prompted him to develop his skills in pastels and oils, demonstrating a resilient artistic spirit.

In terms of personality, contemporary accounts suggest Humphry could be somewhat sensitive and perhaps prone to melancholy. There's an anecdote concerning a commission where a client, a Mr. B, was dissatisfied with a portrait of his wife, feeling Humphry had not made her appear sufficiently youthful or "smiling." Humphry's written response, defending his artistic integrity and pointing out the lady's actual age and his own advanced years, reveals a man of principle but perhaps also a certain irascibility when his professional judgment was questioned.

His financial situation was often precarious, despite his royal appointments and a steady stream of commissions. The Indian venture, undertaken partly to secure his finances, did not yield the expected fortune. Like many artists of the period, he likely faced the constant challenge of managing income and expenses in a profession subject to the whims of fashion and patronage.

In his later years, Humphry's eyesight failed almost completely, effectively ending his painting career around 1797. He spent his final years in Hampstead, then a village outside London. He died on March 9, 1810, and was buried in St. James's Chapel, Hampstead Road.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Ozias Humphry's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as one of the leading British miniaturists of the late 18th century, a period often considered a golden age for the art form. His miniatures are prized for their elegance, sensitivity, and technical finesse, holding their own alongside those of contemporaries like Richard Cosway, John Smart, and George Engleheart.

His contributions to pastel painting are also significant. As Portrait Painter in Crayons to the King, he helped to maintain the prestige of this medium in Britain. His pastels are admired for their soft, luminous qualities and their refined portrayal of sitters.

While his oil paintings may be less celebrated, his work in India provides an important visual record of a key period in Anglo-Indian history. These portraits of Indian rulers and officials offer a European perspective on the subcontinent's elite.

Perhaps one of his most enduring, if indirect, contributions to art history is his patronage of William Blake. By commissioning and collecting Blake's work, Humphry provided crucial support to an artist of extraordinary originality and helped to preserve works that might otherwise have been lost. His notes on George Stubbs also provide invaluable biographical material for one of Britain's greatest animal painters.

Historically, Humphry is seen as a highly skilled and versatile artist who successfully navigated the competitive art world of Georgian England. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary impact of a Reynolds or a Gainsborough, or the visionary intensity of a Blake or a Henry Fuseli, he produced a body of work characterized by consistent quality, elegance, and a deep understanding of the art of portraiture. His career reflects the ambitions, challenges, and opportunities available to artists in his time, from the traditional training grounds of London and the Grand Tour to the newer, more exotic horizons of India. He remains an important figure for understanding the breadth and depth of British art during a period of remarkable creativity and expansion, a peer of artists like Thomas Lawrence who would come to define the next generation of British portraiture.

Conclusion

Ozias Humphry's journey from a young boy captivated by paintings in Devon to a Royal Academician and Portrait Painter to the King is a testament to his talent, diligence, and adaptability. He mastered the intimate art of the miniature, embraced the delicate medium of pastel, and ventured into the complexities of oil painting, all while contending with personal challenges like failing eyesight. His travels to Italy and India broadened his artistic and personal horizons, enriching his work and contributing to the cultural exchange of his era. Through his art, his patronage, and his friendships, Ozias Humphry left an indelible mark on the landscape of 18th-century British art, a master of capturing the likeness and spirit of his age with grace and enduring skill.