William Kennedy (1859-1918) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century Scottish art. A prominent member of the progressive group of artists known as the "Glasgow Boys," Kennedy contributed to a radical shift in Scottish painting, moving away from the sentimental and anecdotal traditions of the Victorian era towards a more robust, naturalistic, and often impressionistic approach. His work, characterized by its strong compositions, confident brushwork, and keen observation of light and atmosphere, captured the essence of Scottish rural life, military themes, and the changing face of the modern world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Scotland

Born on July 17, 1859, in Hutchesontown, a district of Glasgow, William Kennedy's early life was set against the backdrop of a city rapidly industrializing yet still deeply connected to its surrounding countryside. This duality would later inform his artistic vision. His initial artistic training commenced at the Paisley School of Art, a respected local institution. It was here that his talent began to blossom, evidenced by his winning of a prestigious prize in 1875. This early success likely solidified his resolve to pursue a career as a painter.

Following his studies in Paisley, Kennedy further honed his skills, likely engaging with the burgeoning artistic community in Glasgow. The city was becoming a vibrant hub for artists seeking new modes of expression, distinct from the more conservative Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. The atmosphere was ripe for change, with young painters looking towards continental Europe, particularly France, for inspiration. Kennedy was part of this generation, eager to absorb new ideas and techniques.

The Parisian Sojourn: Embracing French Realism

Like many ambitious young British artists of his time, William Kennedy recognized the importance of studying in Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. In Paris, he studied under influential academic painters such as Gustave Boulanger and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, but it was the work and teachings of artists associated with French Realism and Naturalism that made the most profound impact on him.

Key among these influences was Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose plein-air (open-air) approach to painting and his depictions of rural peasant life resonated deeply with Kennedy and his compatriots. Bastien-Lepage's technique, which combined meticulous detail with a broader, more atmospheric handling of landscape, offered a compelling alternative to staid academicism. Kennedy also absorbed the lessons of other French masters like Jean-François Millet, whose dignified portrayals of peasant labor were legendary, and Gustave Courbet, the arch-realist. He also studied under Tony Robert-Fleury, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and later, with Raphaël Collin, Gustave Courtois, and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, further steeping himself in the contemporary currents of French art. This period was crucial in shaping his artistic direction, instilling in him a commitment to direct observation and a desire to capture the unvarnished truth of his subjects.

The Glasgow Boys: A Scottish Avant-Garde

Upon his return to Scotland, Kennedy became a central figure in the formation and activities of the "Glasgow Boys." This loose collective of artists, active from about 1880 to 1900, shared a common desire to break free from the narrative and sentimental constraints of earlier Scottish painting. They championed realism, naturalism, and the tonal qualities of Whistler, alongside the plein-air techniques learned from French painters like Bastien-Lepage and the Barbizon School artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny.

The Glasgow Boys were not a formal school with a manifesto, but rather a group of friends and colleagues who often painted together, exhibited together, and supported each other's artistic endeavors. Key members included James Guthrie, who became a leader of the group, John Lavery, known for his elegant portraits and depictions of modern life, George Henry and E.A. Hornel, who famously collaborated on "The Druids: Bringing in the Mistletoe" and were influenced by Japanese art, Arthur Melville, a master of watercolour, E.A. Walton, Joseph Crawhall, and Alexander Roche. Kennedy was highly respected within this circle, known for his strong personality and his dedication to their shared artistic ideals. He served as the first president of the Glasgow Art Club, a testament to his standing among his peers.

The group often worked in rural communities, such as Cockburnspath and Brig o' Turk, seeking authentic subjects and the opportunity to paint directly from nature. Their work was characterized by a square brush technique, an emphasis on tonal harmony, and a preference for everyday scenes over historical or mythological narratives. They gained international recognition, exhibiting successfully in London, Munich, Vienna, and other European cities, challenging the dominance of the London and Edinburgh art establishments.

Kennedy's Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

William Kennedy's style evolved from his training and his association with the Glasgow Boys. He was a versatile painter, comfortable with landscapes, figurative subjects, and scenes of contemporary life. His brushwork was typically vigorous and direct, conveying a sense of immediacy and a robust engagement with his subject matter. He had a fine sense for colour and tone, often employing a palette that was rich yet controlled, capable of capturing the subtle atmospheric effects of the Scottish climate.

A significant portion of his oeuvre is dedicated to rural themes. He painted farm workers, pastoral landscapes, and animals with an unsentimental eye, focusing on the dignity of labor and the quiet beauty of the countryside. These works reflect the influence of Bastien-Lepage and Millet, but with a distinctly Scottish sensibility. His landscapes often feature dramatic skies and a strong sense of place, capturing the rugged character of the Scottish terrain.

Military subjects also held a particular fascination for Kennedy. He painted numerous scenes featuring Highland soldiers, often in moments of repose or everyday activity rather than grand battle scenes. These works are notable for their humanizing portrayal of the soldier's life, rendered with an attention to detail in uniform and accoutrements, but also with a focus on the individual. This interest in military themes distinguished him somewhat within the Glasgow Boys, many of whom focused more exclusively on rural or urban genre scenes.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several paintings stand out in William Kennedy's body of work, illustrating his skill and artistic concerns.

_Stirling Station_ (1887): This is arguably one of Kennedy's most important and innovative works. Painted with a keen eye for the hustle and bustle of modern life, it depicts passengers alighting from a train at Stirling Station. The painting is a remarkable example of naturalism, capturing a fleeting moment with a sense of immediacy. The complex composition, the interplay of figures, steam, and the station architecture, and the subtle rendering of light demonstrate Kennedy's mastery. It can be seen as a Scottish response to the interest in modern urban scenes explored by French Impressionists like Claude Monet (e.g., his Gare Saint-Lazare series) or Gustave Caillebotte, though Kennedy's approach remains rooted in a more solid, realistic tradition.

_The Deserter_ (1888): This powerful figurative work, now in the collection of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, showcases Kennedy's interest in military themes and his ability to convey narrative and emotion. The painting depicts a captured soldier, his expression a mixture of defiance and despair, being led away. The somber tones and the stark realism of the scene create a poignant commentary on the harsh realities of military life. The painting’s dimensions (119.5cm × 152.5cm) give it a commanding presence.

_A Shepherdess_ (c. 1890-1895): Housed in the Yale Center for British Art, this painting is a fine example of Kennedy's rural genre scenes. It portrays a young woman with her flock, rendered with a sensitivity to the pastoral ideal yet grounded in realistic observation. The treatment of light and landscape reflects the plein-air principles he embraced, and the figure of the shepherdess is imbued with a quiet dignity. Such works connected with a broader European interest in rural subjects, seen in the work of artists like Léon-Augustin L'hermitte in France or Giovanni Segantini in Italy, though Kennedy's interpretation is distinctly his own.

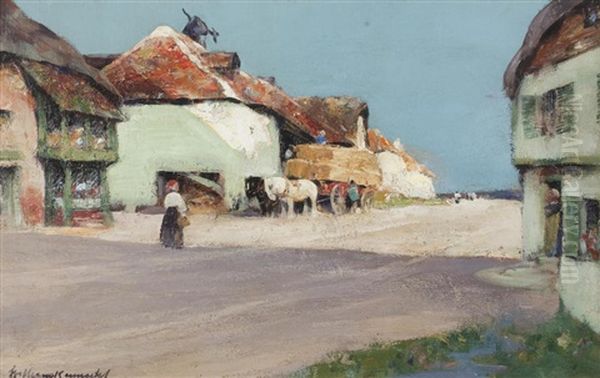

Other notable works include "Homewards," depicting figures returning from the fields at dusk, "A Spring Day," and "The Haycart," all of which demonstrate his commitment to capturing the rhythms of rural life and the changing seasons. His paintings of soldiers, often set in the rugged Scottish Highlands, further explore themes of national identity and the human element within military structures.

Exhibitions and Recognition

William Kennedy was a regular exhibitor at major art institutions throughout his career. He showed his work at the Royal Academy in London, the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, and the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts, which was a key venue for the Glasgow Boys. His participation in these exhibitions helped to raise the profile of the Glasgow School and to challenge the established artistic tastes of the time.

The Glasgow Boys, including Kennedy, also achieved significant recognition on the international stage. Their work was well-received at the Grosvenor Gallery in London, a more progressive alternative to the Royal Academy. Crucially, they made a major impact at the Munich International Exhibition of 1890, where their fresh, vigorous style was acclaimed, influencing German artists and contributing to the rise of Secession movements in Munich and Vienna. Kennedy also exhibited at the prestigious Salon des Artistes Français in Paris, further cementing his reputation beyond British shores. This international exposure was vital for the Glasgow Boys, as it validated their artistic direction and brought Scottish art to the attention of a wider European audience. Artists like Max Liebermann in Germany and members of the Hague School in the Netherlands, such as Jozef Israëls and Anton Mauve, were exploring similar realist and naturalist themes, creating a shared European artistic dialogue.

Later Career, Influence, and Legacy

William Kennedy continued to paint actively into the early 20th century, remaining a respected figure in the Scottish art world. While the initial revolutionary impact of the Glasgow Boys had somewhat lessened as new artistic movements like Post-Impressionism and Fauvism emerged, Kennedy and his colleagues had irrevocably changed the course of Scottish art. They had established a tradition of painterly realism and naturalism that would influence subsequent generations of Scottish artists, including the Scottish Colourists like S.J. Peploe and F.C.B. Cadell, who, while developing their own vibrant style, built upon the Glasgow Boys' legacy of looking to French art and embracing bold brushwork.

Kennedy's dedication to his craft, his leadership within the Glasgow Art Club, and his consistent production of high-quality work ensured his lasting importance. He spent some time in Berkshire, England, and also in Tangier, Morocco, broadening his subject matter, though he remained fundamentally a Scottish painter. His depictions of military life, in particular, offer a valuable historical and artistic record.

William Kennedy passed away in 1918. His death marked the end of an era for Scottish art, but his contributions, and those of the Glasgow Boys, had laid a strong foundation for the development of modern art in Scotland. His work is represented in major public collections, including the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the National Galleries of Scotland, and the Yale Center for British Art, ensuring that his artistic vision continues to be appreciated.

The Wider Context: Contemporaries and Influences

To fully appreciate William Kennedy's contribution, it is essential to see him within the rich tapestry of late 19th-century art. His primary artistic circle was, of course, the Glasgow Boys: James Guthrie, John Lavery, E.A. Walton, George Henry, E.A. Hornel, Joseph Crawhall, and Arthur Melville were his closest colleagues, sharing studios, sketching trips, and a rebellious spirit against the academic art of the day, much like the earlier Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt) had challenged the Royal Academy in their time, albeit with very different stylistic aims.

The profound influence of French art cannot be overstated. Jules Bastien-Lepage was a guiding star for many of the Glasgow Boys, including Kennedy. His blend of photographic realism in the figures with a looser, more impressionistic handling of the landscape was widely emulated. The Barbizon School painters – Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny – with their emphasis on plein-air painting and humble rural subjects, also provided a crucial precedent. Gustave Courbet’s defiant realism was another touchstone.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the American expatriate artist, was another significant influence, particularly his aestheticism, his emphasis on tonal harmonies, and his "art for art's sake" philosophy. Whistler's subtle palettes and decorative arrangements found an echo in the work of several Glasgow Boys.

In a broader British context, the Newlyn School in Cornwall, with artists like Stanhope Forbes and Frank Bramley, shared many of the Glasgow Boys' concerns, particularly their interest in French plein-air realism and their depiction of rural fishing communities. While distinct, both groups represented a move towards a more truthful and direct engagement with contemporary life. Kennedy's work, therefore, was part of a wider European trend towards realism and naturalism, a reaction against the perceived artificiality of academic art and a desire to connect with the realities of the modern world and the enduring rhythms of nature. His contemporaries also included the great French Impressionists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, though the Glasgow Boys generally maintained a more solid, structural approach to form than their French counterparts, aligning more with the realism of Bastien-Lepage than the broken color and light effects of High Impressionism.

Conclusion

William Kennedy was a painter of considerable talent and conviction. As a leading member of the Glasgow Boys, he played a vital role in revitalizing Scottish art at the end of the 19th century. His commitment to naturalism, his skillful handling of paint, and his diverse subject matter – from the bustling energy of _Stirling Station_ to the poignant drama of _The Deserter_ and the tranquil beauty of _A Shepherdess_ – mark him as an important artist of his generation. He successfully synthesized influences from French Realism with a distinctly Scottish sensibility, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. Though perhaps not as widely known today as some of his Glasgow School contemporaries like Lavery or Guthrie, William Kennedy's contribution was integral to the group's success and to the broader narrative of British art's engagement with European modernism. His paintings remain a testament to a pivotal moment of change and innovation in Scottish art history.