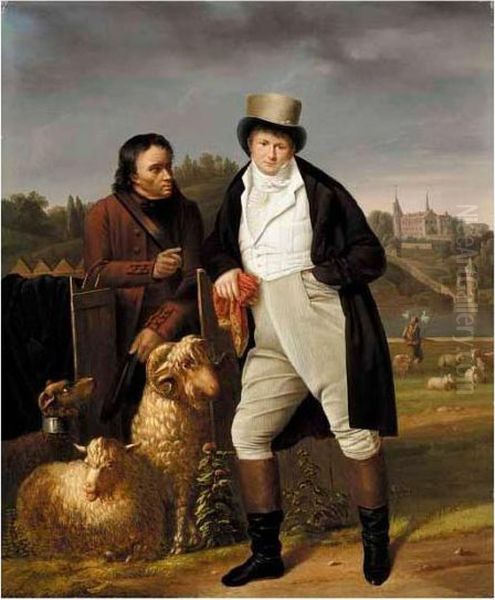

Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer stands as a significant figure in Swiss art history, primarily celebrated for his contributions to landscape painting and watercolour during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born in the vibrant city of Geneva, which was then an independent republic, Töpffer navigated a period of significant political and artistic change in Europe. His work reflects both a deep appreciation for the natural beauty of his homeland and a keen, often humorous, observation of the society around him. Beyond his own artistic achievements, he is also remembered as the father of Rodolphe Töpffer, a pioneering figure widely credited as one of the inventors of the modern comic strip.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer was born in Geneva on May 20, 1766. Geneva, a center of Calvinism and Enlightenment thought, provided a unique cultural backdrop for the young artist. While details of his earliest training are not extensively documented, it is known that he initially pursued artistic skills within his native city. His talents developed, leading him to seek further refinement abroad.

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Töpffer looked towards Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world at the time. Towards the end of the 18th century, he traveled to the French capital to study at the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts. This period would have exposed him to the dominant Neoclassical trends championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David, although Töpffer's own path would lean more towards landscape and genre scenes, eventually embracing elements closer to burgeoning Romantic sensibilities. His time in Paris honed his technical skills and broadened his artistic horizons before he returned to Switzerland.

A Pioneer of Swiss Landscape Painting

Upon returning to his homeland, Töpffer established himself primarily as a painter of landscapes. He worked extensively in both Geneva and Lausanne, capturing the picturesque scenery of the Lake Geneva region and the surrounding Alpine foothills. His approach was rooted in careful observation of nature, a practice that aligned him with the growing interest in depicting the local environment with greater fidelity.

Töpffer became particularly known for his mastery of watercolour. This medium allowed him to capture the subtle effects of light and atmosphere, rendering the textures of rocks, foliage, and water with sensitivity. His style is often described as naturalistic, focusing on the specific details of the landscape rather than purely idealized or classical compositions. He paid close attention to the play of light on surfaces and the intricate forms found in nature, such as the gnarled bark of trees or the delicate structure of leaves.

A key figure in Töpffer's development as a landscape artist was his contemporary, the Swiss painter Pierre-Louis de la Rive (1753-1817). Töpffer and de la Rive shared an interest in exploring the Swiss landscape directly. They are considered among the pioneers of plein-air (open-air) painting in Switzerland, venturing out into the countryside to sketch and paint directly from nature. This practice was relatively innovative at the time and contributed significantly to the development of a distinctly Swiss school of landscape painting, moving away from purely studio-based conventions inherited from artists like the great French classical landscape painters Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

The Art of Observation: Style and Technique

Töpffer's artistic style is characterized by its precision and clarity, combined with a gentle, often lyrical, sensibility. His watercolours, in particular, showcase a sophisticated handling of the medium. He used washes of transparent colour layered to create depth and luminosity, while finer details were often added with delicate brushstrokes or pen lines. His palette tended towards naturalistic tones, capturing the greens, blues, and earthy colours of the Swiss countryside accurately.

His focus on naturalism is evident in his studies of specific elements within the landscape. He rendered trees, rocks, and water with an almost scientific attention to detail, yet without sacrificing artistic expression. This approach reflects the broader Enlightenment-era interest in empirical observation and the natural world, which influenced many artists and thinkers of the period. His work provided a bridge between the more formalized landscapes of the 18th century and the burgeoning Romantic appreciation for the specific character and mood of a place.

While primarily a landscape artist, Töpffer also incorporated figures into his scenes, often depicting rural life or travelers within the landscape. These genre elements add narrative interest and provide a sense of scale, grounding the majestic scenery with human presence. His work can be seen as part of a lineage that influenced later Swiss landscape painters such as François Diday and his student Alexandre Calame, who became famous for their dramatic Alpine scenes.

Representative Work: Tree Study

Among Töpffer's known works, Tree Study serves as an excellent example of his style and focus. Although perhaps not as famous as grander compositions, such studies reveal his meticulous approach to observing and rendering nature. The work, likely executed in watercolour, focuses intently on the form and texture of trees.

Descriptions suggest a composition that highlights the intricate details of bark, moss, and foliage. Töpffer's skill in capturing the tactile qualities of these natural elements – the roughness of the bark, the dampness of moss clinging to the trunk – is evident. The background is often kept simple, perhaps with washes of green indicating the surrounding terrain, ensuring that the viewer's attention remains fixed on the central subject: the tree itself as a complex natural form. Such studies were crucial for building his understanding of landscape elements, which he would then incorporate into larger, more finished compositions.

Satire and Social Commentary

Beyond his serene landscapes, Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer possessed a sharp wit and a talent for caricature and satire. This aspect of his work reveals a different facet of his artistic personality, one engaged with the social and political currents of his time. Geneva, with its history of intellectual debate and political discourse, provided fertile ground for satirical commentary.

Töpffer created drawings and possibly prints that offered humorous or critical observations on contemporary society and politics. Sources mention that he produced works critiquing perceived flaws in constitutional matters, using his art as a vehicle for expressing discontent or highlighting societal absurdities. This satirical vein connects him to a broader European tradition of graphic satire, practiced by artists like William Hogarth in England earlier in the 18th century, and later by Honoré Daumier in France during the 19th century.

His ability to blend keen observation with humour likely influenced his son, Rodolphe. The Töpffer household seems to have been one where art, observation, and perhaps a degree of playful critique were part of daily life, creating an environment conducive to the development of Rodolphe's unique narrative talents. Wolfgang-Adam's own ventures into short stories and plays, as mentioned in some sources, further underscore his multifaceted creative interests beyond painting.

Teaching and Esteemed Patronage

Töpffer's reputation extended beyond the circle of fellow artists and local collectors. His skill as a painter, particularly in the refined art of watercolour, brought him to the attention of high-profile individuals. Notably, he served as a drawing master to members of European royalty and aristocracy.

Among his most distinguished pupils were Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia (wife of Tsar Paul I) and Joséphine de Beauharnais, who would become Empress Joséphine of France as the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. Providing instruction to such prominent figures speaks volumes about Töpffer's standing and the desirability of his artistic skills during his time. This connection to elite circles likely enhanced his reputation and provided valuable patronage, supporting his career as an independent artist. Teaching watercolour painting was a common way for skilled artists to supplement their income, and Töpffer's royal connections indicate he was highly regarded in this capacity.

The Töpffer Legacy: Father and Son

Perhaps one of Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer's most enduring legacies is indirect, through his son, Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846). While Wolfgang-Adam achieved considerable recognition in his own right, Rodolphe gained international fame and historical significance as a writer, teacher, and, most importantly, as a pioneer of sequential graphic narratives.

Rodolphe is often called the "father of the comic strip" or "inventor of the graphic novel" for his "histoires en estampes" (picture stories), such as Les amours de M. Vieux Bois (published circa 1837, later pirated in the US as The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck) and Histoire de M. Jabot. These works combined simple, expressive drawings with handwritten text placed beneath the panels, telling humorous stories through a sequence of images.

The artistic environment created by Wolfgang-Adam undoubtedly played a role in Rodolphe's development. Growing up with a father who was a skilled draftsman, landscape painter, and occasional satirist likely provided both inspiration and informal training. Rodolphe initially pursued art but turned more towards writing and his unique graphic storytelling partly due to vision problems. His innovative work caught the attention of none other than the great German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who praised Rodolphe's picture stories, recognizing their novelty and charm. The father's artistic practice and the son's groundbreaking narrative experiments mark the Töpffer family as a significant force in Swiss cultural history.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer continued to work and live in the Geneva region throughout his life. He remained an active figure in the local art scene, respected for his contributions to landscape painting and his role as a teacher. His dedication to capturing the Swiss environment helped solidify landscape as a major genre within Swiss art, moving beyond the portraiture that had dominated earlier periods, exemplified by artists like the Genevan pastellist Jean-Étienne Liotard.

He witnessed significant changes in the art world during his long career, from the dominance of Neoclassicism in his youth, through the rise of Romanticism which celebrated nature and emotion – elements resonant in his own work – and towards the increasing realism of the mid-19th century. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot in France were developing landscape painting in new directions, while in Britain, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable were revolutionizing the genre with their atmospheric and expressive styles. Töpffer's work occupies a space within this evolving tradition, representing a distinctively Swiss contribution focused on careful observation and the refined use of watercolour.

Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer passed away in Geneva on August 10, 1847, at the age of 81. He left behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, its sensitive portrayal of the Swiss landscape, and its occasional satirical edge. His influence can be seen not only in the works of subsequent Swiss landscape painters like Jacques-Laurent Agasse, Diday, and Calame, but also in the unique artistic path forged by his son Rodolphe, whose innovations continue to echo in the world of comics and graphic novels today. Töpffer remains a testament to the rich artistic heritage of Geneva and Switzerland during a pivotal era in European art history, standing alongside contemporaries who shaped the transition from Neoclassicism, like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, to the expressive freedom of Romantic artists like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix.