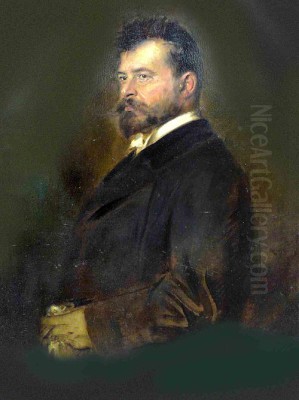

Adolf Hengeler (1863-1927) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Kempten, Bavaria, and later passing away in Munich, Hengeler carved a multifaceted career as a painter, a highly proficient illustrator, and a sharp-witted caricaturist. His work, deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of Munich, offers a window into the societal norms, humors, and anxieties of his time. He was particularly celebrated for his satirical contributions, which appeared in popular publications and resonated with a broad audience.

Hengeler's artistic journey was firmly rooted in the rich artistic environment of Munich, then a major European art center rivaling Paris and Vienna. His development was shaped by the prevailing academic traditions and the burgeoning modern movements that characterized the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His legacy is one of an artist who skillfully navigated the worlds of fine art and popular graphic media, leaving behind a body of work that is both entertaining and insightful.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Munich

Adolf Hengeler's formative years as an artist were spent under the tutelage of Wilhelm von Diez (1839-1907) at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. Diez was a prominent figure in the Munich School, known for his genre paintings, historical scenes, and animal studies, often imbued with a subtle humor and a painterly, realistic style. This mentorship undoubtedly influenced Hengeler, particularly in his appreciation for narrative detail and his ability to capture the essence of everyday life. The Munich Academy at this time was a crucible of talent, attracting students from across Germany and Europe, fostering an environment of rigorous training and artistic exchange.

The influence of Romanticism and Realism, two major artistic currents of the 19th century, can be discerned in Hengeler's oeuvre. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and often an idealized view of nature and the past, may have informed the more sentimental or idyllic aspects of his work. Realism, on the other hand, with its commitment to depicting subjects truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding artistic conventions, or exotic, supernatural elements, provided a foundation for his keen observations of social manners and his satirical critiques. Artists like Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), a leading proponent of Realism in Germany and also active in Munich, championed an unvarnished depiction of rural life, which resonated with the broader trend towards verisimilitude.

The Illustrator and Caricaturist: A Voice in Popular Media

While Hengeler was a capable painter, his most significant impact was arguably in the realm of illustration and caricature. He became a key contributor to the highly popular satirical magazine Die Fliegende Blätter (The Flying Leaves). This weekly publication, founded in 1845, was a German institution, known for its humor, witty social commentary, and high-quality illustrations. Hengeler's involvement placed him in the company of some of Germany's most celebrated graphic artists.

His work for Die Fliegende Blätter often focused on humorous depictions of everyday life, family scenes, and the world of children. These illustrations were characterized by a light, accessible style, keen observation, and an ability to capture charming or amusing moments. Many of these delightful sketches and drawings were later compiled and published in a volume titled Skizzenbuch (Sketchbook), further cementing his reputation as a master of humorous graphic art. His contributions helped shape the visual identity and enduring appeal of the magazine.

Hengeler's talent for caricature extended beyond gentle humor to more pointed social and political satire. In this, he was part of a rich tradition. The 19th century had seen caricature flourish as a powerful tool for social commentary, with artists like the Frenchman Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) setting a high bar with his incisive critiques of French society and politics. In Germany, Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908), a contemporary and colleague, was a towering figure, whose illustrated stories like "Max and Moritz" achieved international fame and profoundly influenced the development of comic strips. Hengeler worked alongside Busch and other notable artists associated with Die Fliegende Blätter, such as Adolf Oberländer (1845-1923) and Emil Reinicke (1859-1942), contributing to a vibrant ecosystem of German graphic humor.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Several of Adolf Hengeler's paintings are held in the collection of the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, a testament to his standing in the city's art scene. Among these are Der Hornbläser (The Horn Blower) from 1899, Der Einsiedler und seine Freunde (The Hermit and His Friends) from 1901, and Der Bauer (The Farmer) from 1902. These titles suggest an interest in genre scenes, character studies, and perhaps a touch of romanticized rural life, themes popular within the Munich School.

One of Hengeler's most striking and politically charged works is the caricature Dragon's Teeth, reportedly created or gaining prominence around 1928, a year after his death, suggesting it was a late-career piece or one that gained particular notice posthumously. This powerful image critiqued American foreign policy, specifically its role in arming various factions globally. The title alludes to the Greek myth of Cadmus sowing dragon's teeth, from which sprang armed warriors, symbolizing how the proliferation of arms inevitably leads to conflict. This work demonstrates Hengeler's capacity for sharp political satire, using visual metaphor to comment on international affairs and the consequences of the arms trade. It shows an artist engaged with the pressing issues of his time, moving beyond purely humorous or decorative concerns.

His broader thematic concerns often revolved around the human condition, viewed through a lens of gentle irony or, at times, more biting critique. The depiction of children and family life, as seen in his Skizzenbuch, reveals a warmth and observational acuity. These works often capture universal moments of childhood play, domestic squabbles, or familial affection, rendered with a characteristic light touch. This focus on the everyday, on the small dramas and comedies of ordinary existence, made his work relatable and enduringly popular.

Artistic Style: Humor, Realism, and a Touch of Romance

Adolf Hengeler's artistic style is characterized by its clarity, technical proficiency, and an inherent sense of humor. His drawing, whether for illustration or as studies for paintings, was confident and expressive. He possessed a knack for capturing characteristic gestures and facial expressions that conveyed personality and emotion with economy and wit. This is particularly evident in his caricatures, where exaggeration is used judiciously to highlight particular traits or absurdities.

The influence of his teacher, Wilhelm von Diez, can be seen in the painterly qualities of some of his works and his interest in genre subjects. However, Hengeler developed his own distinct voice, one that was perhaps less overtly academic and more attuned to the sensibilities of popular illustration. His palette, in his painted works, likely reflected the Munich School's tendency towards a rich, often darker, tonal range, though his illustrations for Die Fliegende Blätter would have been adapted for print reproduction, emphasizing line and clear composition.

While "Romanticism" and "Realism" are broad terms, elements of both can be traced. The romantic sensibility might appear in his more idyllic scenes or in a certain nostalgic charm. The realistic impulse is evident in his careful observation of human behavior and social settings. He was not a radical innovator in the vein of the emerging avant-garde movements like Expressionism, which was gaining traction in Germany during the later part of his career with artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) or Franz Marc (1880-1916) of Der Blaue Reiter group (also Munich-based). Instead, Hengeler operated within a more traditional, yet highly skilled and accessible, artistic framework. His strength lay in his ability to communicate effectively and engagingly with a wide public.

Hengeler in the Context of His Time: Munich and the Graphic Arts

Munich at the turn of the century was a vibrant hub for the arts. The Munich Secession, founded in 1892 by artists like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) and Wilhelm Trübner (1851-1917), signaled a break from the more conservative elements of the established art world, though it was less radical than later Secession movements. While Hengeler was more aligned with the illustrative and academic traditions, the general atmosphere of artistic ferment in Munich would have been part of his environment. The city also fostered a strong tradition in the graphic arts, with numerous illustrated journals and advancements in printing technology.

Hengeler's association with Die Fliegende Blätter places him at the heart of German popular visual culture. This magazine, along with others like Simplicissimus (founded 1896 in Munich), played a crucial role in disseminating art and social commentary to a mass audience. Simplicissimus was known for its sharper, often more politically aggressive satire, featuring artists like Thomas Theodor Heine (1867-1948), Olaf Gulbransson (1873-1958), and Bruno Paul (1874-1968). While Fliegende Blätter often maintained a more genial tone, it was nonetheless an important venue for artists like Hengeler to engage with contemporary society. His work, alongside that of Busch and Oberländer, helped define a particular brand of German humor that was both sophisticated and widely appreciated.

The broader European context for illustration and caricature was also rich. In France, artists like Théophile Steinlen (1859-1923) and Adolphe Willette (1857-1926) were creating iconic poster art and illustrations. In Britain, the tradition of Punch magazine continued, with artists like Linley Sambourne (1844-1910) providing witty visual commentary. Hengeler's work, while distinctly German, participated in this wider European flourishing of the graphic arts. His ability to create compelling narratives and characters within the constraints of print media was a hallmark of his skill.

The Munich Academy and Teaching: Passing on the Tradition

Beyond his prolific output as an artist, Adolf Hengeler also contributed to the art world as an educator. He held a position as a professor at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, the same institution where he had received his training. This role allowed him to influence a new generation of artists, passing on the skills and traditions he had mastered. Teaching at such a prestigious academy was a mark of considerable professional achievement and recognition.

One of his students was Constantin Gerhardinger (1888-1970), who would go on to become a notable painter, particularly known for his landscapes and scenes of Bavarian life. The master-student relationship is a vital conduit for artistic knowledge, and Hengeler's guidance would have shaped Gerhardinger's early development. As a professor, Hengeler would have likely emphasized strong draftsmanship, compositional skills, and perhaps his own keen sense of observation and narrative, qualities evident in his own work. His experience in both painting and the demanding field of illustration would have provided his students with a broad perspective on artistic practice. Other artists who taught or were associated with the Munich Academy around this period included figures like Ludwig von Löfftz (1845-1910), further underscoring the rich academic environment.

Anecdotes and Unique Creations: The Inventive Mind

An interesting, if somewhat eccentric, aspect of Hengeler's creativity is highlighted by an anecdote concerning a unique invention: an animal-driven device. This contraption reportedly involved young bear cubs locked in a circular cage. Meat was used as bait to entice the cubs to chase it, thereby causing the cage (and presumably an attached wheel or mechanism) to rotate. This peculiar invention, while perhaps ethically questionable by modern standards, showcases a playful, inventive, and perhaps slightly mischievous side to Hengeler's personality. It suggests an interest in mechanics and animal behavior, and a mind that explored unconventional ideas, not unlike the fantastical contraptions sometimes seen in the work of illustrators like the French master J.J. Grandville (1803-1847) or the complex, humorous machines of Rube Goldberg (1883-1970) much later in America.

This inventive spirit, even if expressed in unusual ways, aligns with the creativity required of a successful illustrator and caricaturist, who must constantly devise novel visual solutions to convey ideas and humor. It speaks to a mind that was not confined by conventional thinking, a trait that would have served him well in the competitive and fast-paced world of magazine illustration.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Adolf Hengeler's legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled and popular German illustrator and caricaturist who made significant contributions to the visual culture of his time, particularly through his work for Die Fliegende Blätter. He was a master of humorous observation, capable of capturing the charm and absurdities of everyday life with a light and engaging touch. His work provided entertainment and gentle social commentary to a wide readership for many years.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, Hengeler played an important role within his specific domain. He upheld a high standard of draftsmanship and artistic quality in the field of popular graphics, following in the footsteps of Wilhelm Busch and working alongside other talented illustrators like Oberländer and Reinicke. His more satirical works, such as Dragon's Teeth, demonstrate a capacity for pointed critique, showing an artist who was not afraid to engage with more serious political and social issues. The presence of his paintings in the Neue Pinakothek also affirms his recognition as a painter within the Munich art scene.

His influence extended through his teaching at the Munich Academy, shaping younger artists like Constantin Gerhardinger. In the broader narrative of art history, figures like Hengeler are essential for understanding the full spectrum of artistic production in a given period. They represent the vital connection between high art and popular culture, and their work often provides a more immediate and accessible reflection of societal values and concerns than that of the more esoteric avant-garde. Artists like Heinrich Kley (1863-1945), another German contemporary known for his often dark and satirical drawings, also explored themes of industrialization and societal critique, though with a different stylistic approach.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

Adolf Hengeler's art, with its blend of humor, keen observation, and technical skill, retains its appeal. He was an artist who understood his audience and possessed the talent to engage them effectively. Whether through his charming depictions of children, his witty observations of social life, or his occasional forays into sharper satire, Hengeler created a body of work that reflects the spirit of his age. As a painter, illustrator, caricaturist, and professor, he made a distinctive mark on the artistic landscape of Munich and Germany. His contributions to Die Fliegende Blätter ensure his place in the history of German graphic art, and his paintings offer further evidence of his versatile talents. Adolf Hengeler remains a noteworthy figure, an artist whose work continues to offer delight and insight into the world he inhabited.