Alessandro Varotari, more famously known by his moniker Il Padovanino ("the little Paduan"), stands as a significant figure in the transition from the Late Renaissance to the Early Baroque period in Italian art. Born in Padua, a city with its own rich artistic heritage, he became a prominent painter primarily active in Venice, the vibrant heart of the Venetian School. His life and work are inextricably linked with the towering legacy of Titian, an artist whose style Padovanino deeply admired and often emulated, yet he forged an artistic identity that, while indebted to the past, possessed its own distinct character and appeal.

Correct Name and Chronology

The artist's birth name was Alessandro Leone Varotari. He was born in Padua, according to most reliable sources, in 1588. His death is recorded in Venice on July 20, 1649. The nickname "Il Padovanino" directly references his city of origin, distinguishing him in the bustling artistic milieu of Venice where many artists were known by sobriquets related to their birthplace or master. While some earlier accounts might offer slight variations in dates, the 1588-1649 timeframe is the most widely accepted by modern art historical scholarship.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Padua

Alessandro Varotari's journey into the world of art began in his native Padua. He was the son of Dario Varotari the Elder, himself a painter and architect of some repute, though perhaps more known for his architectural work and the artistic lineage he established. Dario, whose own style bore traces of Veronese's influence, likely provided his son with his initial artistic training. Growing up in Padua, Alessandro would have been exposed to the works of earlier Paduan masters like Andrea Mantegna, whose rigorous classicism and sculptural forms had left an indelible mark on North Italian art. He would also have seen works by Venetian masters whose influence extended to the mainland territories of the Serenissima.

This early environment, steeped in both local traditions and the pervasive influence of nearby Venice, laid the groundwork for Padovanino's artistic development. His father's workshop would have been a place of learning not just technique, but also the business of art, preparing him for a professional career. The artistic atmosphere of Padua, while perhaps not as dazzling as Venice, was nonetheless vibrant, with its university fostering intellectual pursuits that often intersected with artistic patronage and theory.

The Move to Venice and the Shadow of Titian

At some point in his early career, likely around 1614, Padovanino moved to Venice. This was a pivotal decision, as Venice was the undisputed center of the "colorito" tradition, emphasizing color, light, and a more painterly approach, in contrast to the Florentine "disegno" which prioritized drawing and line. In Venice, the artistic landscape was overwhelmingly dominated by the legacy of the great masters of the 16th century: Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

Of these, Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) exerted the most profound and lasting influence on Padovanino. Titian, who had died in 1576, was revered as the quintessential Venetian painter, his works celebrated for their rich color, sensuous handling of paint, and profound humanism. Padovanino became a fervent admirer and, in many ways, a disciple of Titian's style. He meticulously studied Titian's compositions, his use of color, and his thematic choices. This was not uncommon; many artists of the period honed their skills by copying the works of established masters.

Padovanino's dedication to Titian's model was so pronounced that he earned the contemporary accolade of being an "emerging Titian" or, as some sources suggest, "our Titian." This speaks volumes about his ability to capture the spirit and technique of the master. He is known to have copied Titian's famous Bacchanals (originally painted for Alfonso I d'Este of Ferrara and later moved to Rome), an experience that would have deeply immersed him in Titian's mythological world and his mastery of dynamic composition and vibrant flesh tones.

Artistic Style: Color, Sensuality, and Narrative

Padovanino's artistic style is characterized by its rich, warm palette, a hallmark of the Venetian tradition. He excelled in rendering sensuous textures, particularly the softness of human flesh, and his female nudes are often imbued with an alluring, if sometimes idealized, beauty. His works frequently display a strong narrative component, whether depicting scenes from mythology, the Bible, or history.

His brushwork, while often refined, could also be expressive, capturing the emotional intensity of his subjects. He had a particular talent for depicting women, often in roles that highlighted their beauty, vulnerability, or dramatic agency. These portrayals, celebrated for their harmonious coloring and aesthetic appeal, became a signature aspect of his oeuvre. While deeply indebted to Titian, Padovanino's figures sometimes possess a slightly more elongated, mannered grace, and his compositions can exhibit a decorative quality that aligns with early Baroque sensibilities.

He managed to navigate the fine line between homage and imitation. While some critics, then and now, might have viewed his close adherence to Titian as a limitation, many contemporaries saw it as a laudable continuation of a glorious tradition. In an era that valued the emulation of proven masters, Padovanino's ability to evoke Titian's style was a mark of skill and understanding.

Major Representative Works and Their Characteristics

Padovanino's body of work includes a range of subjects, with mythological and religious themes being prominent. Several key pieces illustrate his style and his engagement with Titian's legacy:

_Sleeping Venus_ (c. 1625): This subject, famously treated by Giorgione and then Titian (the Venus of Urbino), was a staple of Venetian art. Padovanino's versions, often featuring a reclining nude Venus in a landscape, directly engage with Titian's prototypes. These works showcase his skill in rendering soft flesh tones, luxurious fabrics, and idyllic settings, emphasizing the sensuous appeal of the subject. One such version is noted in private collections.

_Deianira Abducted by the Centaur Nessus_ (c. 1627): This dynamic mythological scene, depicting the dramatic abduction of Hercules' wife, allowed Padovanino to explore movement, emotion, and the contrast between human beauty and bestial force. The composition and energy recall Titian's mythological paintings, such as The Rape of Europa.

_Samson and Delilah_ (or _Solomon and Delilah_ as mentioned in one source, though Samson is more typical for this scene): This biblical story of seduction and betrayal was a popular theme, offering opportunities for dramatic narrative and the depiction of powerful emotions. Padovanino's treatment would have focused on the interplay between the figures, Delilah's allure, and Samson's vulnerability, all rendered with his characteristic rich coloring.

_Adam and Eve before the Body of Abel_: This poignant Old Testament scene depicts the primal grief of Adam and Eve over their murdered son. It highlights Padovanino's ability to convey deep pathos and human tragedy, moving beyond purely decorative or sensuous themes.

_The Marriage at Cana_: Housed in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, this large-scale biblical narrative demonstrates Padovanino's capacity for complex, multi-figure compositions, a skill essential for major public commissions. Such works continued the Venetian tradition of grand, celebratory religious scenes established by artists like Veronese.

_Madonna and Child with Saint Mary Magdalene_: Located in the Louvre, Paris, this work shows his handling of more intimate devotional subjects. The inclusion of Mary Magdalene, often depicted with sensuous beauty even in religious contexts, aligns with Padovanino's skill in portraying compelling female figures.

His works found their way into important collections across Europe, attesting to his contemporary reputation. Besides the Gallerie dell'Accademia and the Louvre, his paintings are held in numerous other museums and private collections, reflecting the demand for his Titian-esque style.

The Roman Sojourn and Its Impact

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Padovanino traveled to Rome, likely in the early 1610s, before settling more permanently in Venice. Rome offered a different artistic environment, one where the classical tradition, High Renaissance masterpieces by Raphael and Michelangelo, and the emerging Baroque style of artists like Annibale Carracci and Caravaggio held sway.

During his time in Rome, Padovanino continued his study of Titian by copying the Bacchanals (specifically The Andrians and The Worship of Venus), which were then in the Aldobrandini collection. This direct engagement with Titian's masterpieces in a different artistic context likely reinforced his commitment to the Venetian master's style. However, his Roman stay also exposed him to other influences. He would have encountered the classicizing naturalism of Annibale Carracci and the Bolognese school, as well as the dramatic tenebrism of Caravaggio and his followers.

Some art historians suggest that elements from Roman art, perhaps the more structured compositions of the Carracci school or the heightened drama found in Baroque painting, subtly filtered into his work. He is also said to have been influenced by Palma Giovane, a prolific Venetian painter of the generation after Titian, whose style blended Venetian colorism with Mannerist tendencies. While Padovanino's core allegiance remained with Titian, his Roman experience likely broadened his artistic vocabulary and understanding of contemporary trends.

Workshop, Students, and Artistic Circle

Back in Venice, Padovanino established a successful workshop and became an influential teacher. He played a role in transmitting the Venetian tradition, particularly his interpretation of Titian's style, to a new generation of artists. Among his notable pupils were:

Pietro Liberi (1605–1687): Liberi became a prominent Venetian painter known for his eclectic style, which combined Venetian color with Roman and Bolognese influences. He was particularly skilled in mythological and allegorical subjects, often with a pronounced sensuality that may reflect Padovanino's influence.

Giulio Carpioni (1613–1678): Carpioni developed a distinctive style characterized by small-scale mythological and bacchanalian scenes, often with a dreamlike, poetic quality. His refined technique and elegant figures show a debt to the Venetian tradition passed down through Padovanino.

Bartolomeo Scaligero (or Scaligeri): Less famous than Liberi or Carpioni, Scaligero was another artist who trained in Padovanino's workshop, helping to propagate his master's style.

Padovanino's sister, Chiara Varotari (1584–1663 or later), was also a painter, primarily known for her portraits. She was an important figure in his life and workshop, likely assisting him with commissions and managing aspects of the studio. The presence of a female artist in a prominent workshop, especially one related to the master, was not unheard of but still noteworthy.

He also had connections with other artists. Pietro della Vecchia (1603–1678), known for his genre scenes, portraits, and sometimes bizarre or macabre subjects, as well as his skillful pastiches of earlier masters like Giorgione and Titian, is said to have worked with Padovanino and been influenced by him. There are also mentions of connections with Jean Leclerc, a French painter and student of the Venetian-influenced German artist Carlo Saraceni. Saraceni himself was a key figure in the transition to Baroque in Rome, known for his Caravaggesque tendencies blended with Venetian color. Such connections indicate Padovanino's integration into a broader network of artists.

Patronage, Reputation, and the "Incogniti"

Padovanino enjoyed considerable patronage from both private collectors and religious institutions. His ability to work in Titian's vein made his paintings desirable for those who admired the High Renaissance master but sought new works. He was also connected with intellectual circles in Venice. Notably, he is said to have created works for the Accademia degli Incogniti, a libertine-leaning intellectual society founded by Giovanni Francesco Loredan.

This association is significant because the Incogniti were known for their free-thinking, often anti-clerical views, and their interest in classical literature and philosophy, sometimes with erotic undertones. Padovanino's paintings for this group might have included mythological scenes with a more pronounced sensuality, catering to the sophisticated and somewhat risqué tastes of its members. This demonstrates his versatility and his ability to adapt his art to different types of patrons and intellectual currents.

His connection with prominent collectors like Gianfrancesco Sagredo, a nobleman and a friend of Galileo Galilei, further underscores his standing in Venetian society. Sagredo was a discerning patron of the arts and sciences, and his support would have enhanced Padovanino's reputation.

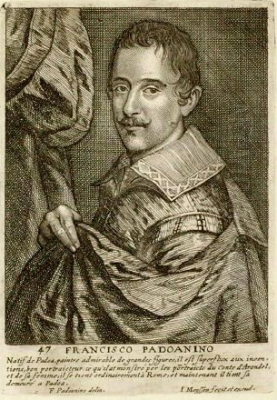

Later Years, Legacy, and the Self-Portrait

Padovanino remained active in Venice for most of his career, continuing to produce works that upheld the Venetian pictorial tradition. In his later years, his style may have evolved towards a more delicate and decorative manner, though the core influence of Titian remained.

A significant act towards the end of his life was the donation of his self-portrait to his native city of Padua. This gesture, common among artists wishing to leave a lasting memorial, speaks to his attachment to his origins and his awareness of his own artistic standing. The self-portrait would have served as a testament to his achievements and a way for Padua to honor one of its notable artistic sons.

He died in Venice in 1649, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a legacy carried on by his students. His impact was primarily in perpetuating and reinterpreting the Titianesque tradition at a time when new Baroque currents were emerging from Rome and Bologna.

Critical Reception and Historical Evaluation: Imitator or Innovator?

The historical evaluation of Alessandro Padovanino has often revolved around the question of his relationship with Titian. He has been, at times, criticized for being overly dependent on Titian's style, essentially an imitator rather than an innovator. This critique, however, often overlooks the complexities of artistic practice in the 17th century, where emulation of established masters was a valued skill and a legitimate means of artistic expression and learning.

More recent scholarship tends to view Padovanino's engagement with Titian not as mere copying, but as a "complex dialogue." He was not just replicating Titian's forms but actively reinterpreting them, adapting them to the tastes of his own time, and, in doing so, forging his own artistic identity. His works, while clearly indebted to Titian, often possess a distinct mood, a different sensibility in the rendering of figures, or a unique compositional twist.

His emphasis on sensuous female figures, the richness of his palette, and his narrative skill were his own contributions, even if they operated within a Titianesque framework. He successfully carved out a niche for himself as a leading exponent of Venetian colorism in the early to mid-17th century, a period when the artistic scene was becoming increasingly diverse. Artists like Bernardo Strozzi, a Genoese painter who moved to Venice, and the "tenebrosi" (painters influenced by Caravaggio's dramatic light and shadow) were introducing different stylistic currents.

Padovanino's enduring appeal lay in his ability to evoke the golden age of Venetian painting while subtly infusing it with contemporary sensibilities. He provided a vital link between the High Renaissance masters and later Baroque painters in Venice. His role as a teacher was also crucial in ensuring the continuity of certain aspects of the Venetian tradition.

Anecdotes and Controversies

While not a figure shrouded in dramatic scandal like Caravaggio, some aspects of Padovanino's life and work offer points of interest:

The Imitation Debate: As discussed, the central "controversy" or critical debate surrounding Padovanino is the extent of his originality versus his imitation of Titian. This was likely a topic of discussion even in his own time.

Religious vs. Secular/Erotic Themes: His work for the Accademia degli Incogniti, with its potential for more overtly erotic content, might have contrasted with his more conventional religious commissions. This duality reflects the diverse demands of patronage and the multifaceted nature of Venetian culture, which could accommodate both piety and worldly pleasures. It is a testament to his versatility that he could navigate these different thematic realms.

Family Workshop: The close collaboration with his sister Chiara Varotari is an interesting aspect of his workshop practice, highlighting the role of family in artistic enterprises of the period.

Social Standing: His role as a witness at the wedding of Lorenzina and Giacomo Pighi, as mentioned in some documents, suggests a respectable social standing within the Venetian community, beyond just his artistic endeavors.

Conclusion: A Venetian Bridge Between Eras

Alessandro Varotari, Il Padovanino, was more than just an epigone of Titian. He was a highly skilled and successful painter who played a crucial role in sustaining and evolving the Venetian pictorial tradition in the 17th century. His deep admiration for Titian provided the foundation for his art, but upon this foundation, he built a body of work that possessed its own lyrical beauty, sensuous appeal, and narrative power.

He served as a bridge, connecting the monumental achievements of the Venetian High Renaissance with the emerging sensibilities of the Baroque. Through his own paintings and through the students he trained, Padovanino ensured that the legacy of Venetian colorism, with its emphasis on light, atmosphere, and painterly execution, continued to flourish. His works, found in major collections worldwide, remain a testament to his talent and his enduring place in the rich tapestry of Italian art history. He remains a key figure for understanding the artistic currents in Seicento Venice, a master who skillfully navigated the legacy of giants while asserting his own distinct, and often captivating, artistic voice.