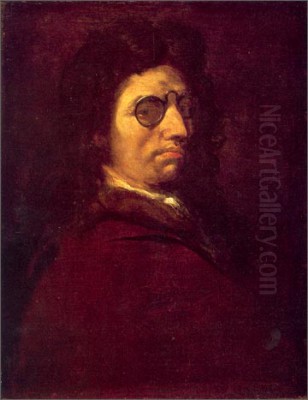

Luca Giordano stands as one of the most formidable and fascinating figures of the Italian Baroque. Born in Naples in 1634 and active until his death there in 1705, he was a painter and etcher whose astonishing speed of execution and prolific output earned him the enduring nickname "Luca Fa Presto" – "Luca paints quickly." His career spanned the latter half of the 17th century, a period of rich artistic development, and he became a dominant force not only in his native Naples but also in Florence, Rome, Venice, and notably, at the Spanish court in Madrid. His technical brilliance, stylistic versatility, and immense productivity left an indelible mark on European art, bridging the High Baroque with the emerging Rococo.

Early Life and Training in Naples

Luca Giordano's artistic journey began in the vibrant, tumultuous city of Naples, a major European cultural center under Spanish rule. He was born into an artistic family; his father, Antonio Giordano, was also a painter, likely providing his son's earliest instruction. The most significant formative influence, however, came when Luca entered the workshop of the preeminent Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera, known as "Lo Spagnoletto," around 1650. Ribera, a follower of Caravaggio, was renowned for his dramatic tenebrism, intense realism, and often somber, philosophical subject matter.

Under Ribera's tutelage, the young Giordano absorbed the master's powerful style. His early works often reflect Ribera's influence, characterized by strong chiaroscuro (contrasts of light and shadow), earthy palettes, and a focus on the physical and psychological intensity of his subjects, frequently depicting saints, martyrs, and philosophers. This grounding in the Neapolitan tradition, heavily shaped by Caravaggio and Ribera, provided a solid foundation for his later stylistic explorations.

Travels and Stylistic Metamorphosis

Giordano was not content to remain solely within the Neapolitan milieu. Driven by ambition and a thirst for knowledge, he embarked on crucial journeys throughout Italy, absorbing diverse artistic influences that would profoundly shape his mature style. His travels took him to Rome, the heart of the Baroque, where he encountered the works of masters from different eras. He studied the monumental classicism of Raphael and other Renaissance giants, refining his understanding of composition and form.

Crucially, in Rome, Giordano was exposed to the dynamic and decorative High Baroque style exemplified by Pietro da Cortona. Cortona's vast, swirling ceiling frescoes, blending Venetian color with Roman grandeur, offered a powerful alternative to the starker realism of the Caravaggisti. Giordano learned from Cortona's ability to orchestrate complex, multi-figure compositions filled with light and movement, a skill that would become central to his own large-scale decorative projects.

His travels also included significant time in Florence and Venice. In Venice, he immersed himself in the rich colorism and painterly traditions of the Venetian Renaissance, particularly the works of Titian and Veronese. The opulent palettes, luminous atmospheres, and grand decorative schemes of these masters resonated deeply with Giordano. He also absorbed the influence of the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens, whose dynamic compositions and vibrant energy were widely admired in Italy. These encounters encouraged Giordano to move away from the darker tones of his early Ribera-influenced phase towards a brighter, more luminous, and highly decorative manner.

The 'Fa Presto' Phenomenon

Giordano's remarkable ability to synthesize these varied influences – the realism of Ribera, the grandeur of Cortona, the color of the Venetians, the energy of Rubens – contributed to his most famous characteristic: his incredible speed. The nickname "Luca Fa Presto" reportedly originated from his father urging him to work faster to earn more, but it quickly became synonymous with his prodigious talent and efficiency. He possessed an extraordinary visual memory and technical facility that allowed him to work at a pace that astounded contemporaries.

This speed was not merely a gimmick; it was intrinsically linked to his mastery of technique and his chameleon-like ability to adopt different styles. He could reportedly paint in the manner of almost any famous master upon request, a skill that, while sometimes drawing criticism for lack of originality, made him exceptionally versatile and highly sought after by patrons. His rapid execution enabled him to undertake vast decorative cycles and produce an enormous body of work, including oil paintings, large-scale frescoes, and etchings, cementing his reputation throughout Italy and beyond.

His productivity was legendary. It was said he could paint a large altarpiece in a single day or complete vast ceiling frescoes in remarkably short periods. This efficiency, combined with his undeniable skill, allowed him to dominate the art market, fulfilling commissions for churches, palaces, and private collectors across the continent.

Major Commissions in Italy

Before his extended period in Spain, Giordano secured and executed numerous prestigious commissions in Italy, showcasing his evolving style and growing reputation. In his native Naples, he was constantly in demand. He painted significant works for the Certosa di San Martino, a vast monastic complex overlooking the city, contributing impressive frescoes that demonstrated his mastery of large-scale narrative and illusionistic space. His dramatic Christ Driving the Merchants from the Temple for the Church of the Gerolamini remains a powerful example of his High Baroque energy.

His fame spread northwards. In the 1680s, he was called to Florence to execute one of his most celebrated works: the ceiling frescoes in the gallery of the Palazzo Medici Riccardi. These frescoes, depicting the Apotheosis of the Medici Dynasty and mythological scenes in the library, are a triumph of his mature style. They combine luminous color, dynamic movement, and complex allegorical programs, transforming the architectural space into a dazzling spectacle. The work showcases his absorption of Venetian and Roman influences, creating a light-filled, airy effect that anticipates the Rococo.

While perhaps less documented than his work elsewhere, Giordano also undertook commissions in Venice, further cementing his reputation as a pan-Italian master capable of adapting to diverse regional tastes while leaving his own distinctive mark. His ability to manage large workshops efficiently was crucial to handling these concurrent and demanding projects.

The Spanish Decade: Court Painter to Charles II

The pinnacle of Giordano's international success came in 1692 when he was summoned to Madrid by King Charles II of Spain. The Spanish Habsburg monarchy, though in decline, still commanded immense prestige, and the invitation to become court painter was a significant honor. Giordano remained in Spain for a decade, from 1692 to 1702, leaving behind an astonishing legacy of work that profoundly influenced Spanish art.

His most extensive Spanish project was the decoration of the Royal Monastery of El Escorial, the imposing palace-monastery complex built by Philip II. Giordano painted vast fresco cycles on the ceilings of the grand staircase (The Glory of the Spanish Monarchy) and the vaults of the basilica. These works are characterized by their immense scale, teeming figures, brilliant light, and complex allegorical content, celebrating the Habsburg dynasty and the Catholic faith. They represent the culmination of his decorative ambitions, transforming the severe architecture of El Escorial with Baroque dynamism.

Beyond El Escorial, Giordano worked extensively in Madrid, decorating ceilings in the Buen Retiro Palace (much of which is now lost) and the Casón del Buen Retiro (where his frescoes survive). He also painted the magnificent ceiling fresco in the Sacristy of Toledo Cathedral. During his time in Spain, he inevitably absorbed influences from Spanish masters, particularly the legacy of Diego Velázquez, whose painterly technique and sophisticated portraiture were highly esteemed. Giordano also produced numerous oil paintings for the King and other patrons, including portraits, religious scenes, and mythological subjects.

His decade in Spain was immensely productive, further solidifying his "Fa Presto" reputation. He managed a large workshop, training Spanish artists and disseminating his style. His departure in 1702, following the death of Charles II and the turmoil of the War of the Spanish Succession, marked the end of a significant chapter in both his career and the history of Spanish painting.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Luca Giordano's style is best characterized as High Baroque, marked by dynamism, emotional intensity, rich color, and complex compositions, particularly suited to large-scale fresco decoration. However, his defining trait was his stylistic versatility, his ability to paint "in the manner of" various masters. While this eclecticism was central to his success, it also led to debates about his originality. He could shift from the dark drama reminiscent of Ribera or Caravaggio to the luminous, airy elegance inspired by Veronese or Cortona, depending on the commission's demands.

His subject matter was broad, though he primarily focused on religious and mythological themes, reflecting the dominant patronage demands of the era. He painted countless altarpieces, scenes from the lives of saints, Old and New Testament narratives, and episodes from classical mythology. Works like The Fall of the Rebel Angels (c. 1665) showcase his ability to handle complex, dynamic compositions filled with figures in dramatic motion. His mythological paintings, such as The Abduction of Helen (c. 1665) or depictions of Ixion, allowed for explorations of sensuality and movement. He also produced historical scenes, allegories (like The Four Continents), and portraits, notably of his royal patron, Charles II of Spain.

Technically, Giordano was a virtuoso. His brushwork was fluid and confident, capable of both detailed rendering and broad, energetic strokes. His use of color became increasingly brilliant and luminous throughout his career, moving towards the lighter palettes that would characterize the Rococo. He excelled in fresco, mastering the challenges of working on wet plaster on a vast scale, creating breathtaking illusionistic effects that seemed to open up ceilings to the heavens. His drawings and etchings also reveal his skill and energy.

Key representative works that encapsulate his achievements include the aforementioned frescoes in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi (Florence) and El Escorial (Spain), the decorations in the Certosa di San Martino (Naples), and oil paintings like Christ Driving the Merchants from the Temple (Naples) and The Dream of Solomon (Prado, Madrid).

Workshop, Pupils, and Influence

Given his prolific output and the scale of his commissions, Giordano relied heavily on a well-organized workshop. He trained numerous assistants and pupils who helped him execute his vast projects and who subsequently carried his influence forward. Among his notable pupils and followers were figures central to the next generation of Neapolitan painting, including Paolo de Matteis and Nicola Malinconico. Other artists associated with his studio or influenced by him include Aniello Rossi, Matteo Pacelli, Giuseppe Simonelli, Juan Antonio Boujas, Nunzio Ferraiuolo, Giovanni Battista Lama, and Andrea Miglionico.

Giordano's impact extended far beyond his direct pupils. In Naples, he revitalized the local school, moving it beyond the dominant influence of Ribera towards a more decorative, pan-Italian Baroque style. His work provided a crucial link between the High Baroque and the emerging Rococo style of the 18th century. Artists like Francesco Solimena, the leading Neapolitan painter after Giordano, built upon his legacy.

His influence was felt throughout Italy and especially in Spain, where his frescoes set a new standard for monumental decoration. His impact can be seen in the work of later 18th-century masters like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, whose airy, light-filled ceiling frescoes owe a debt to Giordano's innovations. Even the great Spanish master Francisco Goya is thought to have looked closely at Giordano's work, particularly his free brushwork and dramatic compositions, during his own formative years. Giordano played a key role in disseminating the late Italian Baroque style across Europe.

Critical Reception and Enduring Controversy

During his lifetime, Luca Giordano enjoyed immense fame and success. He was celebrated for his technical skill, his speed, and his ability to satisfy patrons across Europe. His works were highly valued, and he achieved considerable wealth and status. However, his reputation has fluctuated over the centuries, and his work has often been a subject of critical debate.

The very qualities that brought him fame – his speed and eclecticism – also became grounds for criticism. Some later critics, particularly those valuing overt originality and profound emotional depth above all else, dismissed him as superficial or merely a brilliant imitator, a pasticheur lacking a truly unique voice. He was sometimes unfavorably compared to artists perceived as more revolutionary or emotionally intense, such as Caravaggio or even his own teacher, Ribera. The sheer volume of his output also led to accusations of uneven quality, with some suggesting his rapid production methods inevitably led to less carefully considered works at times. Questions were raised about whether his market-savvy approach compromised artistic integrity.

In more recent art history, there has been a significant re-evaluation of Giordano's contribution. While acknowledging the validity of some criticisms regarding originality, scholars now place greater emphasis on his extraordinary technical mastery, his role as a brilliant synthesizer of diverse traditions, and his crucial importance in the development of late Baroque and Rococo decorative painting. His ability to manage vast, complex compositions, his innovative use of light and color, and his undeniable influence on subsequent generations of artists are now widely recognized. He is seen not just as "Fa Presto," but as a major figure who shaped the course of European art.

Legacy

Luca Giordano died in Naples in 1705, leaving behind an almost unparalleled body of work scattered across the churches, palaces, and museums of Europe. His legacy is multifaceted. He was a technical prodigy, a master of fresco and oil painting whose speed and skill remain astonishing. He was a pivotal figure in the Neapolitan School and a key transmitter of the Italian Baroque style, particularly to Spain.

His work represents a bridge between the dramatic intensity of the High Baroque and the lighter, more decorative sensibilities of the Rococo. He trained and influenced a generation of artists, ensuring the continuation of the grand decorative tradition. While his status relative to other giants of the Baroque may still be debated, his importance as a prolific, versatile, and hugely influential master is undeniable. Luca Giordano remains a testament to the energy, virtuosity, and decorative splendor of the late Baroque era.