Pietro Berrettini, known to history as Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669), stands as a towering figure in the landscape of Italian art. Born in the Tuscan town of Cortona, from which he derived his moniker, he rose to become one of the principal architects and painters of the High Baroque style in Rome. Alongside his contemporaries Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, Cortona fundamentally shaped the visual culture of the 17th century, leaving an indelible mark on the churches and palaces of the Eternal City and influencing artistic trends across Europe. His work, characterized by dynamic energy, rich color, and breathtaking illusionism, embodies the grandeur and theatricality that define the Baroque era.

Cortona was not merely a painter or an architect; he was a versatile designer, capable of conceiving vast decorative schemes that integrated painting, sculpture, and architecture into a unified whole. His career flourished under the patronage of powerful families, most notably the Barberini, whose support enabled him to undertake some of the most ambitious projects of the age. From soaring frescoed ceilings to innovative church facades, Cortona's vision was consistently expansive, aiming to overwhelm the viewer with a sense of divine glory and earthly power, rendered with unparalleled technical skill and imaginative fervor.

Early Life and Training in Florence and Rome

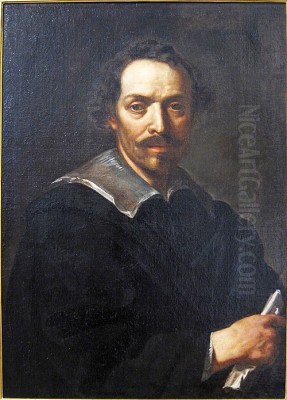

Pietro Berrettini was born in Cortona, Tuscany, in 1596 (some sources cite 1597). His father, Giovanni Berrettini, was a stonemason and architect of modest reputation, providing an early exposure to the building arts. His mother, Francesca Balestrari, reportedly came from a noble background. This mix of artisanal skill and perhaps a degree of social standing may have played a role in his later career trajectory. His initial artistic training took place not in his hometown but in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance.

Around 1609, the young Pietro was apprenticed to the Florentine painter Andrea Commodi. Commodi was a competent but relatively minor figure, yet this Florentine grounding would have exposed Cortona to the city's rich artistic heritage, particularly the works of High Renaissance masters like Andrea del Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo. Around 1612, Commodi relocated to Rome, and Pietro followed him, continuing his apprenticeship. He also spent time in the workshop of Baccio Ciarpi, another Florentine painter working in Rome, known for his competent but somewhat retardataire style.

Rome, however, offered far greater stimuli than the workshops of Commodi or Ciarpi. The city was a vibrant artistic center, buzzing with the legacy of recent masters like Caravaggio and the Carracci, and the burgeoning talents of figures like Bernini. Cortona immersed himself in the study of both ancient Roman sculpture and painting, and the works of Renaissance giants, particularly Raphael and Michelangelo. He was also profoundly influenced by the Venetian tradition, absorbing the rich color and dynamic compositions of Titian and Veronese, likely through works available in Roman collections. Crucially, the classicizing yet dynamic style of Annibale Carracci, whose Farnese Gallery ceiling was a landmark, provided a vital model for large-scale fresco decoration.

During these formative years, Cortona began to attract the attention of discerning patrons. The Sacchetti family, particularly Marcello Sacchetti and his brother Cardinal Giulio Sacchetti, were among his earliest supporters. They commissioned easel paintings and perhaps facilitated his study of important collections. This early patronage was crucial, providing the young artist with opportunities and connections within the complex social and artistic network of Rome. His talent for drawing and his ability to synthesize various influences into a compelling personal style began to distinguish him.

Rise to Prominence: The Barberini Patronage

The trajectory of Pietro da Cortona's career shifted dramatically with the election of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini as Pope Urban VIII in 1623. The Barberini papacy ushered in an era of lavish artistic patronage aimed at glorifying the family and the Church. Urban VIII and his nephews, particularly Cardinal Francesco Barberini, became the most significant patrons of the Roman Baroque, employing artists like Bernini and, increasingly, Cortona.

Cortona's connection to the Barberini circle likely solidified through his earlier association with the Sacchetti family, who were close to the new Pope. An early important commission came around 1624-1626 for frescoes in the church of Santa Bibiana in Rome, a project overseen by Bernini. Cortona painted scenes from the life of the saint, demonstrating his growing mastery of fresco technique and narrative composition. These works, while still showing influences from Domenichino and other contemporaries, already hinted at the more dynamic and painterly style he would fully develop.

His reputation grew steadily. He was admitted to the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's prestigious artists' guild, in 1625, and would later serve as its Principe (president) in 1634-1638. His talent, ambition, and ability to manage large-scale projects made him an attractive choice for the Barberini, who required artists capable of executing their grand vision. Cardinal Francesco Barberini, a learned and discerning patron, became Cortona's staunchest supporter, entrusting him with the commission that would secure his fame and define the High Baroque ceiling fresco.

The Barberini Ceiling: A Baroque Masterpiece

The commission for the ceiling fresco of the Gran Salone in the Palazzo Barberini, the family's newly constructed urban palace, was awarded to Cortona around 1632-1633. Completed by 1639, the Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power remains Cortona's most celebrated work and a defining monument of Baroque art. The vast vault presented an immense canvas for Cortona's burgeoning style, allowing him to unleash the full force of his illusionistic and compositional genius.

The fresco is a stunning example of quadratura, where painted architecture extends the real architecture of the room, blurring the boundary between the viewer's space and the painted heavens. Within a complex fictive framework, Cortona deployed the technique of sotto in sù (meaning "from below, upwards"), depicting figures as if seen from a low viewpoint, soaring into an infinite sky. The central field celebrates Divine Providence commanding Immortality to crown the Barberini coat of arms (featuring bees), which is carried heavenward by virtues. Surrounding scenes depict allegories related to the virtues and achievements of Pope Urban VIII's papacy.

The overall effect is one of overwhelming movement, dazzling light, and vibrant color. Unlike the more compartmentalized approach seen in earlier ceilings like Annibale Carracci's Farnese Gallery, Cortona unified the vast space with swirling masses of figures, dramatic foreshortening, and a sense of boundless energy. The work is a complex theological and political statement, asserting the divine justification of Barberini rule and the glory of the Church under Urban VIII.

The Barberini ceiling established a new benchmark for monumental fresco decoration. Its dynamic, unified, and highly painterly approach stood in contrast to the more restrained, classicizing style advocated by contemporaries like Andrea Sacchi, who favored fewer figures and clearer narratives (leading to a famous debate within the Accademia di San Luca). Cortona's solution proved immensely influential, inspiring generations of artists tackling large ceiling projects across Europe. It remains a breathtaking spectacle, embodying the confidence, drama, and persuasive power of the High Baroque.

Cortona the Painter: Frescoes and Easel Works

While the Barberini ceiling is his most famous painted work, Cortona's career as a painter was prolific and varied, encompassing major fresco cycles in both Rome and Florence, as well as numerous easel paintings. His style continued to evolve, but consistently retained its characteristic energy, rich palette, and integration of figures with their settings.

Between 1637 and 1647, with interruptions, Cortona worked in Florence under the patronage of Grand Duke Ferdinando II de' Medici. His primary task was the decoration of several rooms in the Pitti Palace. In the Sala della Stufa, he painted the Four Ages of Man (Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages), frescoes celebrated for their lyrical beauty and idealized landscapes, showing a slightly softer, more classical vein perhaps influenced by the Florentine context. He then began the decoration of the Planetary Rooms (Sala di Venere, Sala di Giove, Sala di Marte, Sala di Apollo), creating complex allegorical schemes related to Medici virtues and princely education, again employing stunning illusionistic frameworks.

Cortona returned to Rome before completing the Pitti Palace cycle, leaving the Sala di Saturno and other elements to be finished by his most talented pupil and collaborator, Ciro Ferri, who expertly continued his master's style. Back in Rome, Cortona undertook further major fresco projects. For Pope Innocent X Pamphili (Urban VIII's successor), he decorated a gallery in the Palazzo Pamphili in Piazza Navona (1651-1654) with scenes from the Aeneid, displaying a somewhat calmer rhythm compared to the Barberini ceiling but still showcasing his mastery of narrative and illusion.

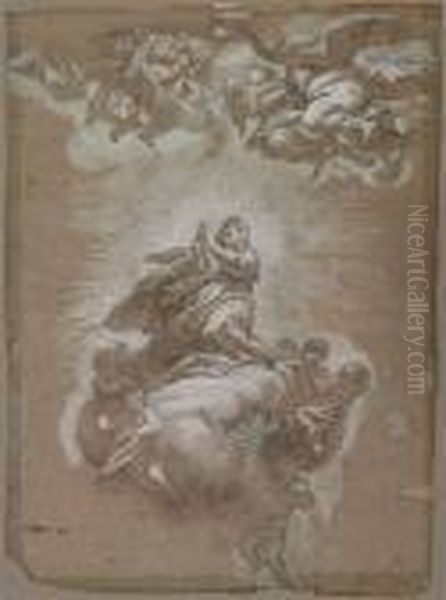

Another significant Roman project was the decoration of the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella), the mother church of the Oratorians. Between 1647 and 1665 (with interruptions), he painted the dome (Trinity in Glory), the apse vault (Assumption of the Virgin), and finally the vast nave vault (Miracle of the Madonna della Vallicella), creating a luminous and uplifting ensemble that seamlessly integrates with the church architecture.

Alongside these monumental frescoes, Cortona produced numerous easel paintings throughout his career. These included religious subjects like The Finding of Moses and Rest on the Flight into Egypt, mythological scenes such as the dynamic Rape of the Sabine Women, allegories, and portraits. He also demonstrated skill in landscape painting, often incorporating classical ruins or biblical narratives, as seen in works like Landscape with the Reconciliation of Jacob and Laban or the poignant Lamentation over the Dead Christ mentioned in the initial sources. His easel works often display the same vibrant color, fluid brushwork, and complex compositions found in his frescoes, though sometimes with greater attention to detail and finish. His style drew inspiration from Venetian colorists like Titian and Veronese, the dynamism of Peter Paul Rubens (who had worked in Italy earlier), and the dramatic potential of light, perhaps indirectly influenced by Caravaggio, though Cortona favored celestial radiance over stark chiaroscuro.

Cortona the Architect: Sacred and Secular Designs

Pietro da Cortona's genius extended equally to architecture. He was not merely a decorator of buildings but a highly original architect in his own right, contributing significantly to the development of the Roman Baroque architectural language. His designs often feature dynamic curves, rich sculptural articulation, and a sophisticated interplay of mass and space, creating structures that are both monumental and engaging.

His most important architectural work is undoubtedly the church of Santi Luca e Martina, located near the Roman Forum. Rebuilt from 1634 onwards, largely at Cortona's own expense (as he was Principe of the Accademia di San Luca, housed there), it is considered one of the earliest and most complete expressions of High Baroque church design. The facade features a novel convex curve, responding dynamically to its urban setting. The interior, based on a Greek cross plan, is a unified space characterized by powerful pilasters, rich stucco work (much executed by his workshop), and carefully controlled lighting, creating an effect of solemn grandeur. Cortona himself chose to be buried here.

Another key architectural intervention was his work at Santa Maria della Pace in Rome (1656-1657). Here, he didn't rebuild the entire church but added a remarkable semi-circular, colonnaded facade. This convex element projects into the small piazza, interacting with the concave wings flanking it, transforming the urban space into a kind of outdoor theatre. It demonstrates Cortona's sensitivity to urban context and his ability to create dynamic spatial experiences through architecture.

Cortona also undertook secular architectural projects. For the Sacchetti family, he designed the Villa Pigneto outside Rome (now destroyed, but known through engravings). This casino, with its innovative use of niches, terraces, and a central concave exedra, was highly influential on later villa design. He also contributed to the Palazzo Barberini, working alongside Bernini and Carlo Maderno, and later designed parts of the Palazzo Pamphili. His architectural style often involved a creative reinterpretation of classical motifs, infused with a Baroque sense of movement and plasticity, mediating perhaps between the more sculptural classicism of Bernini and the complex geometries of Borromini.

He also worked on the facade and interior modifications of the ancient basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura in Rome. Furthermore, during his time in Florence, he produced designs for the facade of the Basilica di San Lorenzo, though these ambitious plans were never executed. These unbuilt projects, known through drawings, further attest to his architectural imagination and his engagement with the legacy of Renaissance masters like Michelangelo, whose work at San Lorenzo remained incomplete.

Workshop, Students, and Influence

Given the scale of his commissions, particularly the vast fresco cycles, Pietro da Cortona necessarily maintained a large and active workshop. He relied on skilled assistants to help prepare cartoons, transfer designs, and execute large areas of painting and stucco decoration under his supervision. This collaborative method was standard practice for major artists of the period.

The most important member of his workshop and his principal artistic heir was Ciro Ferri (1634-1689). Ferri absorbed Cortona's style so completely that he was entrusted with finishing major projects, most notably the Planetary Rooms in the Pitti Palace after Cortona's departure from Florence. Ferri continued to work in a Cortonesque manner throughout his career, helping to perpetuate his master's style into the later Baroque.

Other artists associated with Cortona's studio or influenced by him included Francesco Romanelli, who later achieved success in Paris, carrying a version of the Italian Baroque style to the court of Louis XIV. The Neapolitan painter Luca Giordano, a pivotal figure in the Late Baroque known for his astonishing speed and versatility, was profoundly influenced by Cortona's frescoes during his time in Rome, adapting Cortona's dynamic compositions and luminous palette to his own spectacular ceiling decorations in Naples, Florence, and Madrid. Jacques Courtois, known as Il Borgognone, a specialist in battle paintings active in Rome and Florence, is also sometimes mentioned in connection with Cortona, perhaps indicating the broad reach of Cortona's circle within the Roman artistic milieu.

Cortona's influence extended far beyond his direct pupils. His approach to ceiling decoration, particularly the unified, illusionistic schemes exemplified by the Barberini ceiling, became a dominant model throughout Italy and Catholic Europe. Artists like Giovanni Battista Gaulli ('Baciccio'), who painted the spectacular ceiling of the Gesù church in Rome, clearly built upon Cortona's innovations. His style, disseminated through engravings and the work of his followers, impacted decorative painting in France, Austria, and Southern Germany, contributing significantly to the international language of the Baroque.

Contemporaries and Rivals

Pietro da Cortona operated within one of the most competitive and brilliant artistic environments in history: 17th-century Rome. His career unfolded alongside those of the other two giants of the Roman High Baroque, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) and Francesco Borromini (1599-1667). While sometimes collaborating, particularly early on (like at the Palazzo Barberini), they were also rivals, competing for the most prestigious commissions from popes, cardinals, and noble families. Each possessed a distinct artistic personality: Bernini, the sculptor-architect favored for his dramatic naturalism and classical grandeur; Borromini, the architect known for his complex geometries and intensely personal style; and Cortona, the painter-architect celebrated for his painterly dynamism and decorative richness.

Another significant contemporary and rival, particularly in the field of painting, was Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661). Sacchi represented a more classical and restrained strand within the Baroque, emphasizing clarity, order, and compositional sobriety, drawing heavily on the tradition of Raphael. The famous debate held at the Accademia di San Luca around 1636 pitted Cortona's approach (advocating large, populous compositions) against Sacchi's (arguing for fewer figures and greater narrative focus), highlighting the stylistic tensions within Roman Baroque painting.

Other major artists active in Rome during Cortona's time included the French painter Nicolas Poussin, the leading exponent of classicism, who reportedly admired Cortona's facility while perhaps critiquing his exuberance. The sculptor Alessandro Algardi offered a more classical alternative to Bernini's dramatic style. This constellation of brilliant talents created an atmosphere of intense creativity, dialogue, and competition that spurred the development of the Baroque in all its facets. Cortona navigated this complex world successfully, securing premier commissions and establishing himself as a leading force.

Lesser-Known Aspects and Later Life

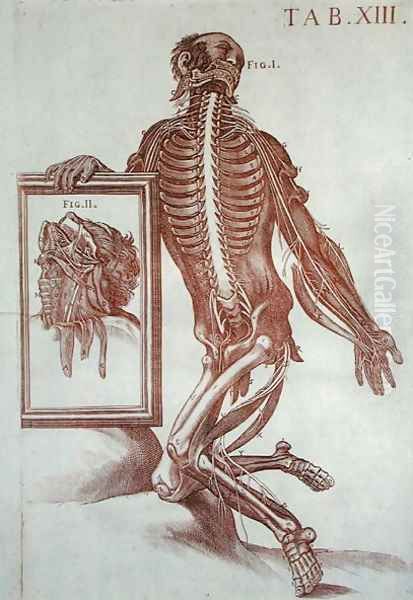

Beyond his major commissions, certain aspects of Cortona's life and work offer further insight into his interests and personality. One intriguing episode involves a series of anatomical illustrations. Around 1618, Cortona apparently produced detailed anatomical drawings, possibly intended for a publication. These drawings, known as the Tabulae Anatomicae, were eventually published much later, in 1741, long after his death. While some sources suggest an initial involvement by Luca Giordano (which seems chronologically problematic for the early date), the plates were published under Cortona's name, indicating his engagement with scientific observation, a common interest among artists since the Renaissance.

Another fascinating, lesser-known activity was his artistic intervention in the subterranean spaces, or catacombs, beneath the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella (Chiesa Nuova) between 1658 and 1665. This work, involving paintings or decorations within the ancient burial sites connected to the church, suggests an interest extending beyond grand public display to more intimate, historically resonant sacred spaces.

Historical accounts sometimes portray Cortona as having a somewhat difficult or proud personality, perhaps a consequence of his success in the competitive Roman environment. However, he also appears to have been deeply pious. He never married and, towards the end of his life, having amassed considerable wealth through his successful career, he reportedly planned to donate much of it to support the cause of a Catholic martyr, and he invested significantly in the rebuilding of his titular church, Santi Luca e Martina.

Pietro da Cortona suffered from gout in his later years, which likely hampered his ability to work. He died in Rome on May 16, 1669, at the age of 72 or 73. He was buried, fittingly, in the church of Santi Luca e Martina, the building that stands as perhaps the most personal testament to his dual genius as architect and devout artist. His legacy was immediately continued by his pupil Ciro Ferri and the many artists influenced by his powerful style.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Pietro da Cortona's contribution to the art of the Baroque period is immense and multifaceted. As a painter, he perfected the High Baroque ceiling fresco, creating dynamic, illusionistic, and unified compositions that became the standard for monumental decoration across Europe. The Barberini Palace ceiling remains one of the defining achievements of the era, a powerful synthesis of artistic skill, complex allegory, and persuasive rhetoric. His ability to blend influences from Venetian color, Roman classicism, and contemporary dynamism resulted in a style that was both learned and exhilarating.

As an architect, Cortona played a crucial role in shaping the Roman Baroque. His designs for Santi Luca e Martina and Santa Maria della Pace introduced innovative approaches to facade design, spatial organization, and urban integration. His architectural work, like his painting, is characterized by a sense of movement, plasticity, and a harmonious fusion of structural form and decorative richness. He provided a compelling alternative to both Bernini's dramatic classicism and Borromini's intricate individualism.

Cortona, alongside Bernini and Borromini, forms the triumvirate that defines the Roman High Baroque. While Bernini's fame may have eclipsed Cortona's in popular perception over time, Cortona's influence on the development of painting, particularly large-scale decoration, was arguably more widespread internationally, impacting artists like Charles Le Brun in France and countless others across the continent. He demonstrated how painting and architecture could be seamlessly integrated to create immersive, emotionally resonant environments that served the purposes of both religious devotion and secular power. Pietro da Cortona remains a pivotal figure, essential for understanding the visual culture of the 17th century and the enduring power of the Baroque imagination.