Jiang Tingxi (蔣廷錫, 1669–1732) stands as a luminous figure in the rich tapestry of Chinese art history, a man whose multifaceted talents saw him excel as a distinguished court official, a respected scholar, a gifted poet, and, most notably for posterity, a preeminent painter of the Qing Dynasty. Flourishing during the reigns of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and early Qianlong emperors, Jiang Tingxi left an indelible mark on the artistic and intellectual landscape of his time. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the cultural efflorescence of the High Qing period, a time of stability and imperial patronage that fostered great achievements in the arts and sciences. This exploration delves into the life, artistic innovations, significant works, and enduring legacy of this remarkable artist.

An Illustrious Life: From Scholar to Statesman

Born in 1669 in Changshu, Jiangsu province, a region renowned for its rich cultural heritage and production of scholars and artists, Jiang Tingxi was destined for a life of intellectual and artistic pursuit. He hailed from a distinguished scholarly family, which undoubtedly provided him with a strong educational foundation from a young age. His innate intelligence and diligence saw him successfully navigate the rigorous imperial examination system, culminating in his attainment of the prestigious jinshi (進士) degree during the Kangxi era. This achievement was the gateway to a distinguished official career.

Jiang Tingxi's capabilities did not go unnoticed by the imperial administration. He rose through the ranks, holding several significant positions, including Vice Minister of Rites and eventually Grand Secretary of the Wenhua Hall (文華殿大學士), one of the highest posts in the imperial bureaucracy. His service spanned the reigns of three influential emperors: Kangxi (康熙), Yongzheng (雍正), and Qianlong (乾隆). As a high-ranking official, he was known for his integrity, diligence, and administrative acumen. He was involved in various state affairs, contributing to the governance and stability of the empire. His official duties, however, did not eclipse his passion for art and scholarship; rather, they often intertwined, with his artistic talents frequently called upon for imperial projects.

Beyond his administrative roles, Jiang Tingxi was also a recognized poet and scholar. His literary talents earned him acclaim, and he was deeply involved in significant scholarly endeavors sponsored by the imperial court. These included contributions to the compilation of the monumental encyclopedia, Gujin Tushu Jicheng (古今圖書集成, Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times), specifically its medical section (Yibu, 醫部). He also participated in the creation of the Huangyu Quanlan Tu (皇輿全覽圖, Complete Map of Imperial Territory), a groundbreaking cartographic project. His courtesy names, Nansha (南沙), Xigu (西谷), and Yangchun (陽春), along with Youjun (酉君) and his sobriquet Qingtong Jushi (青桐居士, Recluse of the Green Parasol Tree), reflect the traditional literati practice of adopting multiple names that often alluded to personal characteristics or aspirations.

The Artistic Genesis: Influences and Early Development

Jiang Tingxi's artistic journey was profoundly shaped by the rich traditions of Chinese painting, particularly the flower-and-bird genre, which had a long and esteemed history. His primary artistic lineage can be traced to Yun Shouping (恽寿平, 1633–1690), one of the "Six Masters of the Early Qing Period." Yun Shouping was a revolutionary figure in flower-and-bird painting, celebrated for reviving and popularizing the mogu (沒骨) or "boneless" technique. This method involved applying colors directly to the paper or silk without preliminary ink outlines, creating a soft, naturalistic effect that emphasized subtlety and elegance.

Jiang Tingxi masterfully adopted and adapted Yun Shouping's mogu technique, making it a cornerstone of his own artistic practice. While Yun Shouping's works often exuded a delicate, almost ethereal quality, Jiang Tingxi infused the style with a greater sense of vibrancy and meticulous detail, perhaps reflecting the opulent tastes of the imperial court he served. His early development would have involved rigorous study of past masters, a common practice for aspiring painters.

As his style matured, Jiang Tingxi also absorbed influences from earlier masters of Chinese painting. The provided information mentions that in his middle age, he incorporated techniques from Shen Zhou (沈周, 1427–1509) and Chen Chun (陳淳, 1483–1544). Shen Zhou, a leading figure of the Wu School during the Ming Dynasty, was known for his robust brushwork and versatility in landscape, figure, and flower painting. Chen Chun, a student of Wen Zhengming (文徵明), was celebrated for his expressive and often spontaneous ink wash paintings of flowers, pioneering a more calligraphic and less detailed approach within the literati tradition. The integration of these diverse influences allowed Jiang Tingxi to develop a style that was both refined and expressive, capable of capturing the delicate beauty of flora and fauna with remarkable precision and artistic flair.

The "Jiang School": Defining a New Aesthetic in Flower-and-Bird Painting

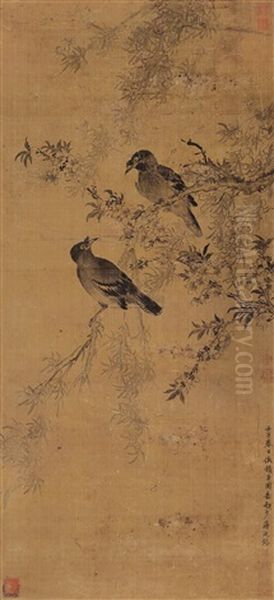

Through his distinctive approach and the high quality of his work, Jiang Tingxi became the progenitor of what art historians refer to as the "Jiang School" (蔣派) of flower-and-bird painting. This school, flourishing within the context of Qing court painting, was characterized by its synthesis of meticulous realism, vibrant coloration, and an underlying literati elegance. It represented a significant development in the flower-and-bird genre, successfully bridging the gap between the detailed, often decorative style favored by the court and the more personal, expressive styles of independent scholar-artists.

The Jiang School emphasized direct observation from life (xiesheng, 寫生), a principle that Jiang Tingxi ardently followed. This commitment to capturing the true essence of his subjects resulted in paintings that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also botanically and ornithologically accurate, a quality highly valued at a court increasingly interested in the natural world. His ability to render flowers in full bloom, insects in intricate detail, and birds with lifelike plumage set a new standard for court painters.

The influence of the Jiang School extended beyond his lifetime. His approach was emulated by his disciples, including members of his own family such as Jiang Pu (蔣溥) and Jiang Shu (蒋淑), as well as other prominent court painters like Zou Yigui (邹一桂, 1686–1772). Zou Yigui, in particular, became a leading flower-and-bird painter of the Qianlong era, further developing the meticulous and colorful style associated with the court, and even authored an important treatise on painting, Xiaoshan Huapu (小山畫譜), which discussed techniques and aesthetics, likely reflecting some of the principles championed by Jiang Tingxi. The Jiang School thus played a crucial role in shaping the direction of courtly flower-and-bird painting throughout much of the 18th century.

Key Characteristics of Jiang Tingxi's Art

Jiang Tingxi's artistic style is marked by several distinctive characteristics that contributed to his renown and the formation of the Jiang School.

Mastery of the Mogu (Boneless) Technique: At the heart of his technical prowess was his exceptional skill in the mogu method. He eschewed strong ink outlines, instead using washes of color and ink to define forms and create volume. This allowed for a seamless blending of hues, resulting in images that appeared soft, luminous, and remarkably lifelike. His flowers, in particular, benefited from this technique, their petals appearing delicate and translucent.

Vibrant and Refined Color Palette: Jiang Tingxi was a consummate colorist. His paintings are characterized by their bright, clear, and often rich colors, yet they avoid any sense of gaudiness. He achieved a harmonious balance, where vibrancy was tempered by elegance. His colors were described as "艳而不俗" (yan er bu su – brilliant but not vulgar), and his ability to blend and layer pigments created subtle gradations and a sense of depth. The interplay of ink and color, with varied tones of wet and dry ink, added further complexity and texture to his works.

Yibi Xiesheng (Freehand Sketching from Life) and Qizheng Xianglü (Harmony of Unconventional and Conventional Elements): His commitment to xiesheng, or sketching from life, imbued his works with a sense of immediacy and accuracy. This was combined with qizheng xianglü, a principle that sought harmony between unconventional (奇, qi) and conventional (正, zheng) elements in composition and execution. This meant that while his paintings were often meticulously detailed and formally composed, they also possessed a dynamic quality and a sense of naturalism that avoided stiffness.

Sino-Western Fusion: An intriguing aspect of Jiang Tingxi's art, and Qing court painting in general during this period, was the cautious and selective incorporation of Western artistic techniques. The presence of Jesuit missionary painters at court, such as Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世寧, Lang Shining, 1688–1766), exposed Chinese artists to European concepts of perspective, chiaroscuro (the use of light and shadow to create volume), and anatomical accuracy. Jiang Tingxi is noted to have employed the "Haixi fa" (海西法, Western method) in works like the Niaopu (鳥譜, Bird Manual), particularly in rendering the texture and three-dimensionality of birds' feathers. This subtle integration of Western elements enhanced the realism of his depictions without fundamentally altering the Chinese aesthetic.

Blend of Literati Elegance and Courtly Opulence: Jiang Tingxi's paintings successfully navigated the often-distinct worlds of literati art and court art. They possessed the meticulous detail, rich colors, and auspicious themes favored by the imperial court, reflecting a sense of "富贵庄重" (fugui zhuangzhong – wealthy and dignified) courtly atmosphere. Simultaneously, his works retained a refined elegance, a poetic sensibility, and often featured calligraphic inscriptions in fluent running script, all hallmarks of the scholar-official (literati) tradition. This fusion resulted in art that was both accessible and sophisticated, appealing to imperial patrons while also satisfying the aesthetic criteria of his fellow scholar-officials.

Masterpieces of a Versatile Brush

Jiang Tingxi was a prolific artist, and many of his works have been preserved, offering testament to his skill and versatility. Several key pieces stand out as representative of his artistic achievements.

Saiwai Huahui Tujuan (塞外花卉圖卷, Scroll of Flowers from Beyond the Borders): This remarkable handscroll is perhaps one of his most scientifically and artistically significant works. It meticulously depicts 66 species of wild plants and flowers encountered in the regions north of the Great Wall, likely inspired by his travels accompanying Emperor Kangxi on imperial tours. The scroll showcases his keen observational skills and his ability to capture the unique characteristics of each plant with botanical accuracy, rendered in his signature mogu style with vibrant colors. The composition is dynamic, creating a sense of a journey through a diverse floral landscape.

Fansong Ren Secai Tuce (仿宋人設色圖冊, Album of Paintings in the Style of Song Dynasty Masters, in Color): This album, consisting of twelve leaves, demonstrates Jiang Tingxi's deep engagement with historical painting traditions. Each leaf depicts various subjects, including flowers, insects, and birds, executed with delicate and fluid brushwork. The colors are described as brilliant yet tasteful, and the overall style is one of refined elegance (yayi, 雅逸). Such albums, imitating earlier masters, were a common way for artists to hone their skills and pay homage to the past, while also showcasing their own interpretive abilities.

Baizhong Mudan Pu (百種牡丹譜, Album of One Hundred Kinds of Peonies): Peonies, symbolizing wealth, honor, and springtime, were a favored subject in Chinese art, especially at court. This album, as its title suggests, features one hundred different varieties of peonies. Each depiction is a testament to Jiang Tingxi's meticulous observation and his ability to capture the subtle variations in form, color, and petal structure of this beloved flower. The work underscores his deep knowledge of horticulture and his technical virtuosity in rendering the "king of flowers" in all its splendor. Often, such albums would include accompanying poems, further enhancing their literary and artistic value.

Lü'e Meihua Tu (綠萼梅花圖, Green Calyx Plum Blossoms): Plum blossoms, admired for their resilience in blooming amidst the late winter snow, are a potent symbol of purity, perseverance, and scholarly integrity. This painting focuses on a branch of green calyx plum blossoms, a specific variety. The depiction would likely emphasize the delicate beauty of the blossoms against a subtle background, conveying a sense of vitality and the quiet strength associated with the subject.

Gouran Huahui Ceye (勾染花卉冊頁, Album of Flowers in Outline and Wash): This album, also comprising twelve leaves, features various flowers such as hibiscus (fuso, 扶桑) and peach blossoms (jiangtao, 绛桃). The term gouran suggests a technique involving outlines filled with washes of color. This indicates Jiang Tingxi's versatility, as he was not solely reliant on the mogu technique but could also employ methods involving clearer ink outlines when the subject or desired effect called for it. The use of varied ink tones to create a sense of three-dimensionality is noted, marking these as representative works of early Qing flower-and-bird painting.

Other notable works mentioned in research contexts include Yuyuan Ruishu Tu (御園瑞蔬圖, Auspicious Vegetables from the Imperial Garden), which likely showcased his ability to elevate common subjects to art through meticulous rendering and perhaps auspicious symbolism, and Cai Gen Xiang (菜根香, Fragrance of Vegetable Roots), a painting that achieved a remarkably high price at auction, underscoring the contemporary market's appreciation for his art. Works like Furong Lusi Tu (芙蓉鷺鷥圖, Hibiscus and Egret) and Shuangya Tu (雙鴨圖, Two Ducks) would further exemplify his skill in the broader flower-and-bird genre, combining floral elements with lively depictions of avian life. His fan paintings, such as Xianglan Shanmian (香蘭扇面, Fragrant Orchid Fan Painting), and thematic works like Jiuri Tu (九秋圖, likely depicting chrysanthemums associated with the ninth day of the ninth lunar month), demonstrate the breadth of his output.

Beyond the Canvas: Botanical Studies and Scholarly Pursuits

Jiang Tingxi's artistic endeavors were often intertwined with his scholarly interests, particularly in the realm of natural history. His meticulous depictions of plants in works like Saiwai Huahui Tujuan and Baizhong Mudan Pu were not merely artistic exercises but also reflected a genuine scientific curiosity and a deep knowledge of botany. These paintings served an almost documentary purpose, recording the flora of specific regions or the diverse varieties of cultivated species. This aligns with a broader trend during the Kangxi and Yongzheng reigns, where the imperial court showed considerable interest in cataloging and understanding the natural world, partly influenced by the empirical methods introduced by Jesuit missionaries.

His involvement in the compilation of the Gujin Tushu Jicheng, particularly its medical section, further highlights his scholarly breadth. This monumental encyclopedia aimed to synthesize all existing knowledge, and contributing to its medical volumes would have required extensive research and a systematic approach to information. Similarly, his participation in the Huangyu Quanlan Tu mapping project demonstrates his engagement with scientific endeavors of national importance. This project, which utilized European cartographic techniques introduced by Jesuits, was a significant achievement of the Kangxi era.

Jiang Tingxi was also a respected poet. His literary works, including collections such as Qingtong Xuan Shiji (青桐軒詩集, Poetry Collection from the Green Parasol Tree Studio) and Pian Yun Ji (片雲集, Floating Cloud Collection), were well-regarded. The prominent scholar and official Song Luo (宋荦) even praised him as one of the "Jiangzuo Shiwu Zi" (江左十五子, Fifteen Masters of Jiangzuo), a testament to his literary standing. His scholarly writings extended to works like Shangshu Dili Jinshi (尚書地理今釋, Contemporary Explication of the Geography in the Book of Documents) and the Jiang Xigu Ji (蔣西谷集, Collected Works of Jiang Xigu). This prolific output across art, poetry, and scholarship paints a picture of a quintessential scholar-official, deeply embedded in the rich intellectual currents of his time.

Interactions and Collaborations: A Nexus of Artistic Exchange

As a prominent court official and artist, Jiang Tingxi moved within a vibrant circle of intellectuals, fellow officials, and artists. His interactions and collaborations were crucial for the exchange of ideas and the development of artistic trends.

He maintained a close relationship with Ma Yuanyu (馬元馭, c. 1669–1722), a fellow native of Changshu and a notable painter. Ma Yuanyu was considered one of the most distinguished disciples of Yun Shouping, and their shared artistic lineage likely fostered a strong connection. It's plausible that they influenced each other's work, both being key figures in perpetuating and evolving the mogu style.

Jiang Tingxi also engaged with other literary and artistic figures like Gu Wenyuan (顧文淵), with whom he would participate in poetry gatherings and discussions on art. His interactions extended to calligraphers such as Zhang Zhao (張照, 1691–1745), another influential court official known for his mastery of calligraphy, suggesting a mutual appreciation for the closely related arts of painting and calligraphy.

A particularly significant aspect of his artistic life was his collaboration with foreign artists at court. Through Prince Yi (怡親王 Yinxiang), a highly influential imperial prince and patron of the arts during the Yongzheng reign, Jiang Tingxi became acquainted with Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining). While the exact nature and extent of their direct collaborations on specific pieces might be subject to further research, the exposure to Castiglione's work and techniques undoubtedly contributed to Jiang's incorporation of Western elements into his painting.

He also collaborated with other Chinese court painters. Records indicate joint works with Tang Dai (唐岱, 1673–c. 1752), a Manchu artist favored by Emperor Kangxi for his landscapes. Their collaborations might have involved Tang Dai painting landscape settings for Jiang Tingxi's floral or faunal subjects, or vice versa, on projects like depictions of red carrots or other specific commissions. Another collaborator was Shen Yuan (沈源, active mid-18th century), with whom Jiang Tingxi reportedly worked on important projects such as the Yuanmingyuan Tu (圓明園圖, Pictures of the Old Summer Palace) and Suichao Tu (歲朝圖, New Year's Day Pictures), the latter being a traditional genre depicting auspicious objects and scenes to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

The "Jiang School" that he founded also implies a master-disciple relationship with painters like his son Jiang Pu and Zou Yigui, who carried forward his stylistic legacy. Furthermore, his style is noted to have influenced later painters in southern China, such as Ju Lian (居廉, 1828–1904) and Ju Chao (居巢, 1811–1865) of the Lingnan School, who were also known for their meticulous and colorful depictions of nature, often employing the mogu technique and emphasizing sketching from life.

Imperial Patronage and Courtly Life

The patronage of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors was a defining feature of Jiang Tingxi's career. The Qing court, particularly during these prosperous reigns, was a major center for artistic production, commissioning vast numbers of paintings for decoration, documentation, and ceremonial purposes. Artists who gained imperial favor, like Jiang Tingxi, enjoyed access to resources, opportunities for significant projects, and the prestige associated with serving the Son of Heaven.

His relationship with Emperor Kangxi appears to have been particularly formative. Jiang Tingxi twice accompanied the emperor on his tours beyond the Great Wall. These expeditions provided him with firsthand exposure to the diverse flora of the northern regions, directly inspiring works like the Saiwai Huahui Tujuan. Emperor Kangxi himself was a patron of learning and the arts, and he reportedly admired the unique plants of these regions, even composing poems about them, such as "Saiwai Huacao Shuyue Tesheng" (塞外花草暑月特盛, Wildflowers and Grasses Beyond the Borders Flourish Exuberantly in Summer Months). This imperial interest likely encouraged and validated Jiang Tingxi's artistic focus on these subjects.

Under Emperor Yongzheng and the early Qianlong reign, Jiang Tingxi continued to enjoy imperial esteem. His paintings were frequently admired and collected by the emperors, often housed in the imperial private collections (migé, 秘閣). His involvement in major imperial scholarly projects like the Gujin Tushu Jicheng further solidified his position at court. The demand for his work was such that, as is common with highly successful court artists, some paintings attributed to him might have been produced by his studio or disciples under his supervision, or even later imitations. This phenomenon of "代筆" (daibi, ghost-painting) and forgery speaks to the high regard in which his art was held.

Anecdotes and the Artist's Persona

Historical accounts and the nature of his work offer glimpses into Jiang Tingxi's persona and creative process. The story of his travels with Emperor Kangxi and the subsequent creation of the Saiwai Huahui Tujuan is a prominent anecdote, highlighting his dedication to observing nature and his responsiveness to imperial interests. This experience underscores a key aspect of his artistic philosophy: the importance of direct engagement with the natural world as a source of inspiration.

His innovative fusion of the mogu technique with elements of Western realism, while maintaining a distinctly Chinese aesthetic, speaks to an open-minded and adaptive artistic intellect. He was not content to merely replicate past styles but sought to refine and expand the expressive possibilities of his chosen genre.

The sheer volume and quality of his output, alongside his demanding official duties and scholarly pursuits, suggest a person of immense energy, discipline, and intellectual capacity. His paintings, often imbued with a sense of tranquility and meticulous beauty, also reflect a deep appreciation for the natural world and perhaps a philosophical outlook that found solace and meaning in its depiction. Works like Xianglan Shanmian (Fragrant Orchid Fan Painting) and Jiuri Tu (Ninth Day of the Ninth Month Chrysanthemums) suggest a man who cherished the refined pleasures of literati life and the changing seasons.

The existence of forgeries and works by disciples attributed to him, while a challenge for connoisseurship, is also an indirect testament to his fame and the desirability of his art. It indicates that his style was influential and widely recognized as a benchmark of quality in flower-and-bird painting.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Historical texts and later art historical assessments consistently accord Jiang Tingxi a significant place in Chinese art and culture. He is lauded for his multifaceted contributions as an upright and capable official, a learned scholar, a talented poet, and a master painter.

As a statesman, he was recognized for his integrity and effectiveness. His efforts in areas like reforming the grain transport system and promoting local education earned him respect and the trust of the emperors he served. His political career provided the stability and access that facilitated his artistic and scholarly endeavors at the highest levels.

Artistically, he is celebrated as the founder of the "Jiang School" of flower-and-bird painting, a style that successfully blended meticulous realism with vibrant color and literati elegance. His mastery of the mogu technique and his subtle incorporation of Western elements were key innovations. Art historians like Zhang Geng (張庚) in his Guochao Huazheng Lu (國朝畫徵錄, Records of Qing Dynasty Painters) likely praised his skill, noting his ability to capture the spirit (qiyun, 氣韻) of his subjects. His influence extended to his disciples and later generations of painters, particularly within the court and in regions like Lingnan.

His scholarly contributions, especially his work on the Gujin Tushu Jicheng and other compilations, were vital for the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. His own writings, both poetry and scholarly treatises, further cemented his reputation as a leading intellectual of his time. Song Luo's inclusion of him among the "Fifteen Masters of Jiangzuo" underscores his contemporary literary acclaim.

Overall, Jiang Tingxi is remembered as a quintessential scholar-official of the High Qing period, a man who embodied the Confucian ideal of service combined with cultural refinement. His ability to excel in diverse fields – politics, scholarship, poetry, and painting – marks him as an exceptionally gifted individual.

Enduring Influence and Academic Scrutiny

The legacy of Jiang Tingxi continues to be recognized and studied in modern times. His paintings are prized possessions in major museum collections worldwide, including the Palace Museum in Beijing and Taipei, the Shanghai Museum, and numerous international institutions. These works serve as invaluable resources for understanding Qing Dynasty court painting, the development of the flower-and-bird genre, and the cultural exchanges between China and the West during the 18th century.

Academic research on Jiang Tingxi covers various facets of his career. Art historians analyze his stylistic development, his technical innovations, his relationship with patrons and fellow artists, and his place within the broader context of Chinese art history. His works are examined for their aesthetic qualities, their iconographic significance, and their reflection of the scientific and intellectual currents of his era. The botanical accuracy of paintings like Saiwai Huahui Tujuan has also attracted interest from scholars of natural history and the history of science in China.

The art market, too, reflects his enduring status. His paintings, when they appear at auction, often command high prices, as evidenced by the sale of Cai Gen Xiang. This market appreciation, while subject to fluctuations, indicates a sustained recognition of his artistic merit and historical importance.

In conclusion, Jiang Tingxi was far more than just a painter; he was a cultural luminary whose life and work epitomized the intellectual and artistic vibrancy of the Qing Dynasty. His contributions as a statesman, scholar, poet, and, above all, as a master of flower-and-bird painting have secured him a lasting place in the annals of Chinese history. His art, characterized by its meticulous beauty, vibrant color, and harmonious blend of traditions, continues to captivate and inspire, offering a timeless window onto the splendors of the natural world as seen through the eyes of a Qing Dynasty master.