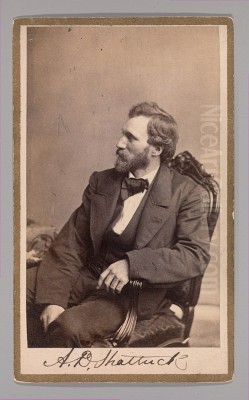

Aaron Draper Shattuck stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the pantheon of 19th-century American art. A prominent member of the second generation of the Hudson River School, Shattuck's canvases offer intimate and meticulously rendered visions of the New England landscape. His work, characterized by its delicate precision, sensitivity to light, and profound appreciation for the natural world, provides a valuable window into the artistic currents and cultural sensibilities of his time. Though his fame may have been eclipsed for a period, a renewed appreciation for his contributions has solidified his place in the annals of American art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on March 9, 1832, in Francestown, New Hampshire, Aaron Draper Shattuck's early life was rooted in the very landscapes that would later define his artistic career. The bucolic environment of rural New England undoubtedly instilled in him a deep connection to nature from a young age. This connection would become the wellspring of his artistic inspiration.

His formal artistic training began in 1851 when he moved to Boston to study portraiture under Alexander Ransom. Ransom, a capable portraitist, would have provided Shattuck with a solid foundation in drawing and the human form. This early focus on portraiture, a common starting point for many aspiring artists of the era, helped Shattuck hone his observational skills and his ability to capture likenesses, skills that would later translate into the precise rendering of natural details in his landscapes. To support himself during these formative years, Shattuck undertook portrait commissions, a practical necessity that also offered valuable experience.

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Shattuck relocated to New York City in 1854. This move was pivotal, placing him at the epicenter of the burgeoning American art scene. He enrolled at the prestigious National Academy of Design, an institution that was central to the development of American art. There, he would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic theories and practices, and crucially, to the work of established and emerging artists of the Hudson River School. His time at the Academy was instrumental in shaping his artistic direction, moving him increasingly towards landscape painting.

The Hudson River School and Rise to Prominence

The mid-19th century was the heyday of the Hudson River School, America's first true school of landscape painting. Artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand had laid the groundwork, imbuing American scenery with a sense of national pride and spiritual significance. Shattuck emerged as part of the second generation, a group that built upon this legacy, often with a greater emphasis on detailed realism and the effects of light and atmosphere, a style that would later be termed Luminism.

Shattuck quickly gained recognition for his talent. His dedication and skill were evident, and he became one of the youngest artists to be elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1859, followed by full academician status in 1861. This was a significant honor, signifying his acceptance into the highest echelons of the American art world. He regularly exhibited his work at the Academy, as well as at other important venues such as the Boston Athenaeum, the Boston Art Club, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, further cementing his reputation.

His summers were dedicated to sketching expeditions, a practice common among Hudson River School painters. These trips were essential for gathering the raw material for his studio compositions. Shattuck's preferred sketching grounds were primarily in New England, particularly the White Mountains of New Hampshire, a region beloved by many of his contemporaries, including artists like Benjamin Champney, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford. He also ventured to the Helderberg Mountains in New York, the pastoral landscapes of Virginia, and the rugged coastline of Maine, particularly Monhegan Island.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Shattuck's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous detail, delicate brushwork, and a profound sensitivity to the nuances of the natural world. His paintings are often intimate in scale, inviting close inspection and revealing a wealth of carefully observed information about flora, fauna, and geological formations. This precision reflects the influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an English art movement whose tenets, championed by the critic John Ruskin, emphasized "truth to nature" and a high degree of finish. Many American artists, including Shattuck, were drawn to Ruskin's ideas.

His handling of light is particularly noteworthy and aligns him with the Luminist painters, such as John Frederick Kensett and Martin Johnson Heade. Luminism, though not a formal movement with a manifesto, describes a tendency in American landscape painting characterized by soft, diffused light, an emphasis on atmospheric effects, serene compositions, and an almost palpable stillness. Shattuck’s works often feature a calm, contemplative mood, with light playing a crucial role in defining form and creating atmosphere.

He was a master of capturing the specific character of a place. Whether depicting a sun-dappled forest interior, a tranquil lakeside, or the rocky coast, his paintings convey a strong sense of verisimilitude. His palette was typically rich and naturalistic, accurately reflecting the colors of the American landscape through the changing seasons. He often favored scenes of quiet beauty rather than the grand, sublime vistas pursued by some of his contemporaries like Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt, though he was certainly capable of capturing a sense of awe.

Shattuck's process involved extensive outdoor sketching, creating detailed studies in pencil and oil that would later be elaborated upon in his studio. This combination of direct observation and careful studio refinement allowed him to achieve both accuracy and a harmonious, composed aesthetic.

Key Themes and Subjects

New England's diverse landscapes provided the primary inspiration for Shattuck. He was particularly drawn to the White Mountains, a region that held almost mythical status for American landscape painters. His depictions of this area capture its unique blend of rugged peaks, dense forests, and sparkling waterways. He often focused on the more intimate aspects of the mountains, such as a quiet stream, a cluster of birch trees, or a sunlit clearing, rather than panoramic mountain ranges.

Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, was another significant location for Shattuck. He first visited the island in 1858 and was captivated by its dramatic cliffs, crashing surf, and the unique quality of its light. He became one of the early artist-pioneers of Monhegan, predating the larger art colony that would flourish there in the later 19th and early 20th centuries with artists like Rockwell Kent and George Bellows. His Monhegan scenes often highlight the raw, untamed beauty of the island.

Beyond these specific locales, Shattuck excelled at portraying the pastoral charm of the American countryside. His paintings frequently feature idyllic scenes of meadows, woodlands, and gentle rivers, often populated with grazing cattle, which added a touch of pastoral serenity and were a popular motif in 19th-century landscape art. These works resonated with a public that increasingly valued the restorative qualities of nature in an era of rapid industrialization.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Shattuck's style and thematic concerns.

"White Mountain Scenery (Mount Chocorua)" (various versions, e.g., c. 1858): This subject, a favorite among White Mountain painters, allowed Shattuck to demonstrate his skill in rendering both majestic mountain forms and intricate foreground details. His versions typically combine a sense of grandeur with a carefully observed depiction of trees, rocks, and water, all bathed in a clear, luminous light.

"The Androscoggin River, New Hampshire" (c. 1864): This work exemplifies his ability to capture the tranquil beauty of a New England river scene. The composition would likely feature calm waters reflecting the sky and surrounding foliage, with meticulous attention to the textures of bark, leaves, and river stones. Such paintings often evoke a sense of peace and harmony with nature.

"Frenchman's Bay, Mount Desert Island, Maine" (c. 1858-1860): Reflecting his coastal explorations, this painting would showcase his ability to depict the interplay of water, rock, and sky. The clarity of light and the detailed rendering of the rugged coastline are characteristic of his Maine subjects, often imbued with a Luminist sensibility.

"Cattle by the Riverbank" (various examples): Shattuck frequently included cattle in his landscapes, a common motif that added a pastoral element and a sense of gentle domesticity to his scenes. These works, such as "Sunday Morning in New England" (1873), often depict cows grazing peacefully or wading in shallow waters, contributing to the overall idyllic mood.

"The Shattuck Family, with a View of Lake Kennebago, Maine" (1865): This painting is particularly interesting as it combines Shattuck's skill in landscape with portraiture. It depicts his own family in an outdoor setting, showcasing a personal connection to the landscape and offering a glimpse into the artist's life. The detailed rendering of both the figures and the surrounding scenery is typical of his meticulous approach.

The Tenth Street Studio Building and Artistic Circle

In 1859, Shattuck took a studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City. This building, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, was the first of its kind in America, specifically constructed to house artists' studios. It quickly became a vibrant hub of artistic activity and social life, home to many of the leading painters of the day.

His neighbors in the Tenth Street Studio Building included some of the most illustrious names in American art. Frederic Edwin Church, known for his monumental South American and Arctic landscapes, had a prominent studio there. Albert Bierstadt, celebrated for his dramatic depictions of the American West, was another neighbor. Shattuck developed close working relationships with these artists, sharing ideas and undoubtedly influencing one another.

He was also friends with John Frederick Kensett, a leading Luminist painter whose serene coastal and inland scenes shared an affinity with Shattuck's own sensibilities. Samuel Colman, another prominent landscape painter, was not only a colleague but also became Shattuck's brother-in-law when Shattuck married Marion Colman. This familial tie further integrated him into the artistic community. Other notable artists associated with the Hudson River School and the New York art scene with whom Shattuck would have interacted include Sanford Robinson Gifford, Jervis McEntee, Jasper Francis Cropsey, known for his vibrant autumnal landscapes, and William Trost Richards, who also shared an interest in Pre-Raphaelite detail. Alfred Thompson Bricher, another artist known for his coastal scenes and Luminist qualities, was also part of this milieu. The Hart brothers, William and James McDougal Hart, were also active landscape and cattle painters during this period. This environment of camaraderie and friendly competition was undoubtedly stimulating for Shattuck's artistic development. He is known to have exchanged works with Kensett and Colman, a common practice among artists that fostered mutual respect and learning.

Later Life, Inventions, and Other Pursuits

Shattuck's active painting career spanned several decades, but by the late 1880s, his output began to decline. A serious illness in 1888 significantly impacted his ability to paint, and he largely ceased artistic production thereafter. However, his creative energies found other outlets.

Shattuck was also an inventor. In 1883, he received a patent for a "Picture-frame Stretcher-key," a device designed to maintain the tension of canvases on their stretchers, preventing sagging. This invention proved to be quite successful and provided him with a steady source of income in his later years, a practical solution to the often-precarious financial situation of artists. Some sources also mention a patent for a type of surgical or wound clamp, indicating a versatile and inventive mind.

After largely retiring from painting, Shattuck moved to Granby, Connecticut, in 1870, and fully embraced a rural lifestyle. He devoted himself to farming, particularly sheep breeding, and beekeeping. He also pursued his interest in music, becoming an accomplished violin maker. This transition from a celebrated painter to a gentleman farmer and craftsman speaks to his multifaceted nature and his enduring connection to hands-on, creative work.

Aaron Draper Shattuck passed away on July 30, 1928, in Granby, Connecticut, at the venerable age of 96.

Legacy and Rediscovery

During his active years, Aaron Draper Shattuck was a respected and successful artist. His paintings were admired for their beauty, technical skill, and faithful representation of American nature. He was an integral part of the Hudson River School and contributed significantly to its development.

However, like many artists of his generation whose styles were rooted in 19th-century realism, Shattuck's reputation waned in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism. The detailed, narrative, and often sentimental qualities of Hudson River School painting fell out of favor with critics and collectors who championed more abstract and avant-garde approaches.

It was not until the mid-to-late 20th century that a significant reassessment of 19th-century American art began. Art historians and curators started to look back at this period with fresh eyes, recognizing the unique contributions and historical importance of artists like Shattuck. His work, along with that of his contemporaries, was "rediscovered," and his paintings began to reappear in exhibitions and command renewed interest in the art market.

Today, Aaron Draper Shattuck's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the New Britain Museum of American Art, and the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, among others. His works are prized for their exquisite detail, their luminous quality, and their evocative portrayal of a 19th-century American landscape that was rapidly changing.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Aaron Draper Shattuck's legacy is that of a dedicated and highly skilled artist who captured the intimate beauty of the American landscape with remarkable fidelity and sensitivity. As a key member of the Hudson River School's second generation, he embraced the prevailing ethos of finding spiritual and national identity in nature, while also infusing his work with a personal vision characterized by meticulous detail and a profound appreciation for the subtle effects of light and atmosphere.

His paintings offer more than just picturesque views; they are carefully constructed compositions that reflect a deep understanding of the natural world and a mastery of artistic technique. From the tranquil forests of New Hampshire to the rugged coast of Maine, Shattuck's art invites viewers to pause and appreciate the quiet splendor of nature. Though his career was curtailed by illness, the body of work he produced remains a testament to his talent and his enduring contribution to the rich tapestry of American art. His rediscovery has rightfully restored him to a place of honor among the painters who defined a pivotal era in the nation's artistic heritage.