Charles Henry Gifford stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century American art. Active during a period of profound national growth and evolving artistic identity, Gifford carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of marine and landscape subjects, primarily associated with the Luminist movement. Born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1839, his life and art were deeply intertwined with the coastal environments of New England. Though largely self-taught, his keen observational skills and innate sensitivity to light and atmosphere allowed him to create intimate, evocative works that continue to resonate with viewers today. His career spanned the tumultuous years of the Civil War and the Gilded Age, reflecting both the enduring beauty of the American landscape and the subtle shifts in artistic sensibilities of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in New Bedford

Charles Henry Gifford entered the world in Fairhaven, a town adjacent to the bustling maritime center of New Bedford, Massachusetts. His family background was rooted in craftsmanship; his father and uncle were carpenters, instilling perhaps an early appreciation for skilled work and structure. While he briefly explored the craft of shipbuilding and reportedly disliked an apprenticeship in shoemaking, his true calling lay elsewhere. The vibrant artistic milieu of nearby New Bedford proved to be a powerful magnet for the young Gifford. This city, enriched by the wealth of the whaling industry, was becoming a notable center for marine painting.

Crucially, Gifford did not receive formal academic training in art. He was, in essence, a self-taught artist, honing his skills through observation, practice, and exposure to the works of established painters in the region. He absorbed lessons from the artistic environment around him, particularly the New Bedford masters whose studios dotted the area. Among his most significant early influences were Albert Van Beest, a Dutch-born marine painter known for his dramatic seascapes, and William Bradford, famed for his Arctic scenes and detailed ship portraits. The towering figure of Albert Bierstadt, already gaining renown for his grandiloquent Western landscapes but with roots in New Bedford, also cast a long shadow, demonstrating the power of landscape painting to capture the American spirit. Gifford learned from their approaches to composition, their handling of light on water, and their dedication to capturing the specific character of maritime life and coastal scenery.

His familial connection to woodworking may have resurfaced in his later proficiency as a frame maker, suggesting a continued link to artisanal traditions even as he pursued the fine arts. This practical grounding, combined with his innate talent, set the stage for a unique artistic journey, one defined by personal discovery rather than academic prescription. The coastal environment wasn't just a subject for Gifford; it was the crucible in which his artistic identity was forged.

Civil War Service and Return to Art

The trajectory of Gifford's burgeoning artistic life was interrupted by the outbreak of the American Civil War. Like many young men of his generation, he answered the call to duty, enlisting in the Union Army. He served with the 5th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. His military career, however, took a dramatic turn when he was captured by Confederate forces during the Battle of New Bern, North Carolina, in 1862. This experience as a prisoner of war, though details are scarce, undoubtedly marked a significant and likely harrowing chapter in his young life.

Following his release and the conclusion of his military service, Gifford returned to his native Massachusetts. He settled back into the familiar environment of Fairhaven and New Bedford, picking up the threads of his artistic aspirations. The war years, while disruptive, did not extinguish his passion for painting. Instead, he seemed to rededicate himself to his craft with renewed focus. By 1868, he had established his own studio in Fairhaven, a clear signal of his commitment to pursuing art as a professional vocation.

This post-war period was crucial for his development. Free from the immediate demands of military life, he could fully immerse himself in observing and rendering the coastal landscapes that had captivated him from his youth. The establishment of a studio provided him with a dedicated space to experiment, refine his techniques, and produce a growing body of work. It marked his transition from an aspiring amateur, influenced by local masters, to a practicing artist developing his own distinct voice and vision. The quiet shores and luminous waters of the New England coast offered a stark contrast to the turmoil of war, perhaps providing a source of solace and inspiration as he solidified his artistic path.

The Luminist Vision: Light, Atmosphere, and Intimacy

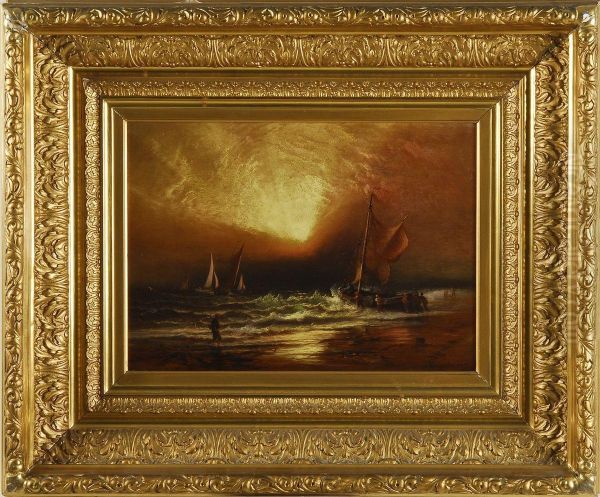

Charles Henry Gifford is most closely associated with Luminism, a distinct current within nineteenth-century American landscape painting. Flourishing roughly between the 1850s and the late 1870s, Luminism is characterized by its profound interest in the effects of light and atmosphere, often rendered with meticulous detail and exceptionally smooth, almost invisible brushwork. Unlike the dramatic, sometimes turbulent scenes favored by earlier Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, Luminist works typically exude a sense of stillness, serenity, and contemplative quietude.

Gifford's paintings exemplify many core tenets of Luminism. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the subtle gradations of light – the soft glow of dawn, the hazy stillness of midday, or the reflective calm of twilight over coastal waters. His compositions often feature strong horizontal elements, emphasizing the expansive tranquility of the sea and sky. Water is frequently depicted as glassy and reflective, mirroring the sky and enhancing the overall sense of peace. Human presence, if included, is usually small and integrated harmoniously within the vastness of nature, reinforcing a feeling of quiet solitude.

While influenced by the Hudson River School's dedication to depicting the American landscape, Gifford, like other Luminists such as Fitz Henry Lane, Martin Johnson Heade, Sanford Robinson Gifford (a contemporary landscape painter, but not a close relative), and John Frederick Kensett, moved towards a more personal and poetic interpretation. The emphasis shifted from the sublime grandeur of untamed wilderness, often seen in the works of Albert Bierstadt or Frederic Edwin Church, towards the intimate beauty found in familiar coastal settings. Gifford's genius lay in his ability to imbue these often small-scale canvases with a palpable sense of place and a specific atmospheric mood, transforming simple coastal views into deeply felt meditations on light and nature. His concealed brushwork further enhances the illusion of reality, inviting the viewer to step into the serene, light-filled world he depicted.

Signature Subjects: The New England Coast and Beyond

The heart of Charles Henry Gifford's artistic output lies in his depictions of the New England coastline and its adjacent islands. He returned time and again to the shores and waters he knew intimately from his upbringing in Fairhaven and New Bedford. The Elizabeth Islands, a chain stretching southwest from Cape Cod, were a favorite locale, particularly Cuttyhunk Island, the outermost island in the chain. Its rocky shores, quiet coves, and expansive views provided endless inspiration. Nantucket Island, with its historic harbors and unique coastal character, also featured prominently in his work.

Gifford's paintings capture the specific essence of these places – the quality of the light filtering through maritime haze, the texture of weathered rocks and sandy beaches, the gentle lapping of waves in sheltered harbors, and the silhouette of sailboats against a luminous sky. He was a master of capturing the subtle interplay between water, land, and atmosphere that defines the New England coast. His focus was often on the quiet moments, the tranquil scenes away from the bustle of the main ports, emphasizing the inherent beauty and serenity of the natural environment.

While primarily known for his coastal scenes, Gifford also ventured inland, notably painting landscapes in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. This region, a popular subject for many Hudson River School and Luminist painters, offered a different kind of natural beauty – rolling hills, dense forests, and picturesque mountain vistas. Even in these inland scenes, however, Gifford often retained his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere, adapting his Luminist approach to capture the unique conditions of the mountain environment. His works, whether coastal or inland, consistently demonstrate his deep connection to the landscapes of the Northeast and his remarkable ability to translate their specific moods onto canvas.

The "Little Gems" and Artistic Technique

A defining characteristic of Charles Henry Gifford's work is its scale. While many of his contemporaries, particularly those associated with the grander aspects of the Hudson River School, favored large, panoramic canvases, Gifford predominantly worked on a much smaller, more intimate scale. Many of his paintings measure less than 9 by 14 inches. This preference earned his works the affectionate moniker "little gems," a testament to their jewel-like quality, refined execution, and concentrated atmospheric power.

Working small did not mean sacrificing detail or impact. On the contrary, Gifford packed these compact canvases with nuanced observations of light, color, and texture. His technique was typically precise and controlled. He applied paint smoothly, often minimizing visible brushstrokes to create seamless transitions between tones and enhance the illusion of reality – a hallmark of the Luminist style. This meticulous approach allowed him to render the subtle effects of light on water, the delicate haze of coastal air, and the precise details of shoreline vegetation or distant sailing vessels with remarkable clarity.

His color palette was often restrained, favoring soft, harmonious tones that accurately reflected the atmospheric conditions he sought to portray. He excelled at capturing the warm, golden light of sunrise or sunset, as well as the cooler, silvery tones of overcast days or twilight. The intimacy of the scale invites viewers to engage closely with the paintings, drawing them into the serene, meticulously rendered worlds Gifford created. These "little gems" were not just small paintings; they were concentrated distillations of place and mood, showcasing Gifford's mastery of his craft and his unique ability to convey profound beauty within a modest format.

Recognition, Success, and Travels Abroad

Despite his self-taught origins and preference for smaller canvases, Charles Henry Gifford achieved notable recognition and commercial success during his lifetime. A significant milestone came in 1876 at the Centennial International Exposition held in Philadelphia. This major event, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the United States Declaration of Independence, featured a vast art exhibition showcasing American artistic achievements. Gifford submitted his painting, Cedars in New England (1876), which was awarded a prestigious Gold Medal. This accolade brought his work to national attention and solidified his reputation as a skilled landscape painter. The painting was lauded, with some critics hailing him as a "pioneer" in depicting the quintessential New England landscape.

This recognition likely contributed to his growing commercial success. His intimate, atmospheric "little gems" found favor with collectors who appreciated their refined beauty and evocative power. Unlike some artists who struggled for patronage, Gifford appears to have managed his career astutely. His success provided him with the means to travel, broadening his horizons beyond the familiar landscapes of New England.

In 1879, Gifford embarked on a significant journey abroad, visiting England, Ireland, and Scotland. This trip offered him the opportunity to experience different landscapes, observe European art collections firsthand, and potentially exhibit his own work to new audiences. While the direct impact of this European sojourn on his subsequent style is not always overtly dramatic, such experiences invariably enrich an artist's perspective. Exposure to the works of British landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner, known for his atmospheric effects, or the pastoral scenes of John Constable, may have resonated with Gifford's own sensibilities. The trip marked a high point in his career, reflecting his established position within the American art scene and his ability to engage with the wider art world.

Distinguishing Giffords: Charles Henry vs. Robert Swain

Navigating the landscape of nineteenth-century American art can sometimes be complicated by artists sharing similar names. This is particularly true in the case of Charles Henry Gifford (1839-1904) and his contemporary and cousin, Robert Swain Gifford (1840-1905). Both artists hailed from the same coastal Massachusetts region (Robert Swain Gifford was born on Nonamesset Island, part of the Elizabeth Islands) and both achieved prominence as painters, leading to occasional confusion between their lives and works. However, their artistic paths and styles diverged significantly.

While Charles Henry Gifford remained primarily focused on Luminist depictions of the New England coast and White Mountains, often on a small scale, Robert Swain Gifford developed a broader range of subjects and a different stylistic approach. R.S. Gifford traveled extensively, not just in Europe but also to North Africa and the Middle East, becoming known for his evocative Orientalist scenes as well as his American landscapes. His style often leaned more towards Tonalism or the influence of the French Barbizon School, characterized by looser brushwork, a more muted palette, and an emphasis on mood and suggestion rather than the crystalline clarity of Luminism. Key Barbizon figures like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet influenced many American artists of this generation, including R.S. Gifford.

Furthermore, Robert Swain Gifford was a prominent figure in the New York art world. He was an early and active member of the influential Tile Club, a social and artistic group founded in New York City. Through the Tile Club, he associated and sketched with leading artists of the day, including William Merritt Chase, J. Alden Weir, Winslow Homer (though Homer's involvement was brief), John H. Twachtman, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. These associations placed R.S. Gifford at the center of progressive artistic circles. While Charles Henry Gifford achieved success and recognition, his career remained more closely tied to his New England roots and the specific aesthetic of Luminism, distinct from the path taken by his slightly younger, more widely traveled, and stylistically different cousin. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for appreciating the unique contributions of each artist.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

In the later stages of his career, towards the turn of the twentieth century, Charles Henry Gifford increasingly turned his attention to watercolor painting. While he continued to work in oils, his exploration of watercolor allowed him to capture the transient effects of light and atmosphere with a different kind of immediacy and fluidity. His proficiency in this medium further demonstrated his versatility and his ongoing commitment to exploring the nuances of the natural world. Works from this period, such as New Bedford from Fairhaven (1899) and Approaching Port Clarence, Alaska (1899) – the latter suggesting perhaps broader travels or work based on sketches from others – show his continued engagement with maritime themes.

Charles Henry Gifford passed away in 1904, leaving behind a significant body of work that captures the serene beauty of the American landscape, particularly the New England coast. While perhaps not as widely celebrated today as some of his Luminist contemporaries like Lane or Heade, or figures from other movements like Winslow Homer with his powerful marine narratives, or George Inness with his deeply Tonalist landscapes, Gifford holds a secure place in the history of American art. His influence lies in his mastery of the Luminist style, his dedication to capturing the specific character of his chosen locales, and his ability to convey profound emotion through subtle renderings of light and atmosphere.

His work stands as a testament to the power of self-directed study and intimate observation. He contributed significantly to the tradition of American landscape painting that sought to define a national identity through the depiction of its natural beauty. His "little gems" continue to be appreciated by collectors and museum-goers for their quiet intensity and technical refinement. Artists like Thomas Eakins pursued rigorous realism, James McNeill Whistler explored aesthetic harmonies, and Mary Cassatt embraced Impressionism, but Gifford remained steadfast in his Luminist vision, offering a unique perspective on the American scene. His legacy endures in the luminous, tranquil canvases that invite viewers to pause and contemplate the quiet beauty of the natural world.

Conclusion: A Master of Light and Place

Charles Henry Gifford navigated the American art world of the latter nineteenth century with a quiet confidence and a distinct artistic vision. Emerging from a background of craftsmanship and self-directed learning in the vibrant maritime community of New Bedford, he became a leading practitioner of Luminism. His life, marked by service in the Civil War and later travels abroad, remained deeply rooted in the coastal landscapes of New England, which formed the core subject of his art.

His preference for intimate scale, resulting in the cherished "little gems," allowed for a concentrated focus on the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere. Through meticulous technique and a profound sensitivity to his environment, Gifford captured the serene harbors, hazy coastlines, and reflective waters of Massachusetts, the Elizabeth Islands, Nantucket, and the White Mountains with unparalleled grace. While sometimes overshadowed by contemporaries with grander ambitions or more dramatic styles, and occasionally confused with his cousin Robert Swain Gifford, Charles Henry Gifford's contribution is unique and enduring.

He stands as a master of light, able to translate the subtle nuances of dawn, dusk, and hazy daylight onto canvas with poetic precision. His works are more than mere topographical records; they are evocative meditations on place, tranquility, and the quiet majesty of nature. As an art historian reflects on the diverse expressions of nineteenth-century American art, Charles Henry Gifford emerges as a vital voice, a beacon of Luminism whose intimate, light-filled canvases continue to offer moments of serene contemplation and profound beauty.