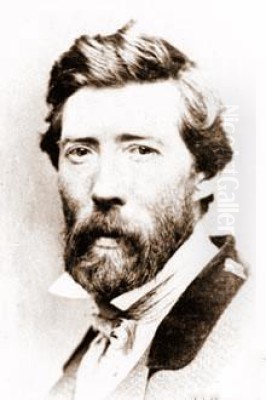

William M. Hart (1823-1894) stands as a significant figure in the annals of American art, a painter whose canvases captured the gentle beauty and tranquil spirit of the 19th-century American landscape. Born in Scotland but intrinsically linked with the artistic flourishing of his adopted homeland, Hart became a leading member of the second generation of the Hudson River School. Renowned for his evocative landscapes, often featuring serene pastoral scenes and meticulously rendered cattle, he contributed significantly not only through his brush but also through his dedication to fostering artistic institutions in America. His work reflects a deep appreciation for nature's subtleties and a mastery of light and detail that cemented his reputation among peers and patrons alike.

From Scotland to Albany: Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

William M. Hart's journey began in Paisley, Scotland, in 1823. The industrial town offered little hint of the artistic path his life would take. His family sought new opportunities across the Atlantic, immigrating to the United States in 1831 and settling in Albany, New York. This move proved pivotal, placing the young Hart in a burgeoning cultural center. His artistic inclinations emerged early, though initially channeled into more practical trades. As a teenager, he found work as a decorative painter, applying his nascent skills to the panels of coaches and carriages – a common starting point for aspiring artists of the era.

This practical work honed his hand-eye coordination and understanding of paint application, but his ambitions soon grew. He transitioned to portraiture, a more respected, albeit often challenging, field for an artist seeking commissions and recognition. Albany provided a community where he could develop his talents. By 1840, at the age of just seventeen, he felt confident enough to open his first formal studio in the city, signaling his commitment to a professional artistic career. He became known within the local art community, gaining experience and likely interacting with other regional artists and patrons, laying the groundwork for his future success.

Finding His Path: The Turn to Landscape

While portraiture offered a path to artistic legitimacy, it proved financially precarious for the young Hart. Seeking more consistent income and perhaps drawn by the growing national interest in the American scenery, he began experimenting with landscape painting. His early landscapes were reportedly sold at modest prices, suggesting an initial period of exploration and development. This shift coincided with a broader cultural movement in America that celebrated the unique beauty and potential of the nation's natural environment. Artists were increasingly venturing into the wilderness and countryside, seeking subjects that resonated with a sense of national identity and romantic idealism.

Hart's artistic development during this period also involved travel. He spent time working in Michigan around the mid-1840s, broadening his exposure to different types of American scenery beyond the Hudson Valley. These formative years were crucial. He was absorbing the visual language of the land and refining the techniques needed to capture its essence. The decision to focus on landscape painting aligned him with the dominant artistic movement of the time, the Hudson River School, whose members were actively defining a distinctly American approach to art, inspired by the majestic and pastoral vistas of the nation.

European Interlude and Return to America

Around 1849, Hart's burgeoning career faced an interruption. Concerns about his health prompted a return trip to his native Scotland. Such trips were not uncommon for American artists seeking either recuperation or further study abroad, though the specifics of Hart's activities during this period are less documented than his American career. It's plausible he observed the works of Scottish landscape painters, potentially absorbing influences from the European art scene. However, his core artistic identity remained firmly rooted in the American landscape tradition he had already begun to embrace.

He returned to the United States around 1852 or 1853, his health presumably improved and his artistic direction clarified. He arrived back with a renewed commitment to landscape painting. Recognizing the importance of the nation's primary art center, he soon relocated from Albany to New York City, establishing himself there by 1853 or 1854. This move placed him at the heart of the American art world, facilitating greater access to patrons, exhibitions, and fellow artists, including the leading figures of the Hudson River School. His focus was now firmly set on capturing the American landscape.

The Hudson River School and Hart's Place Within It

William M. Hart emerged as a prominent figure in the second generation of the Hudson River School. This movement, generally considered the first coherent school of American art, originated in the 1820s with pioneers like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. These artists celebrated the American wilderness, particularly the landscapes of the Hudson River Valley and surrounding regions like the Catskills and New England. Their work often blended detailed realism with elements of Romanticism, conveying awe at nature's grandeur or finding moral and spiritual significance in the landscape.

The second generation, flourishing from the mid-19th century onwards, built upon this foundation. Artists such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Sanford Robinson Gifford, John Frederick Kensett, and Jasper Francis Cropsey, alongside William Hart and his brother James McDougal Hart, often brought a more polished technique and sometimes a greater emphasis on the effects of light and atmosphere – qualities associated with Luminism, a related style. While some, like Church and Bierstadt, pursued dramatic, large-scale canvases of exotic locales, Hart largely focused on the more intimate, pastoral aspects of the American scene, aligning him more closely with the detailed, nature-focused approach championed by Asher B. Durand.

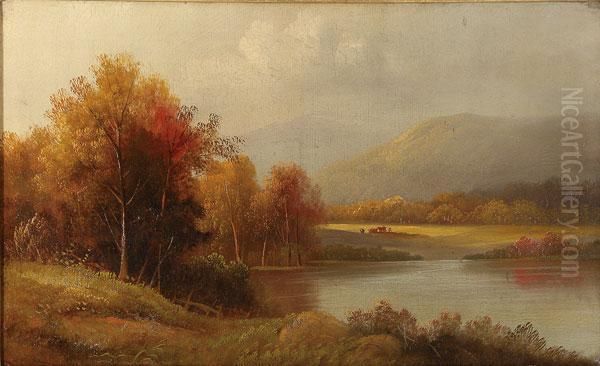

Hart's Artistic Style: Light, Detail, and the Pastoral Ideal

William M. Hart's mature style is characterized by a distinctive blend of meticulous detail and atmospheric sensitivity. His connection to Asher B. Durand is evident in the careful rendering of natural forms – the specific textures of rocks, the intricate branching of trees, the delicate forms of foliage. Durand advocated for direct study from nature, and Hart's work reflects this commitment to empirical observation, grounding his scenes in a believable reality. However, Hart filtered this realism through a gentle, often idealized lens.

He possessed a particular mastery of light. His canvases frequently feature the soft, hazy glow of late afternoon or the warm radiance of a tranquil summer day. He excelled at depicting angled sunlight casting long shadows across fields and highlighting the textures of the landscape. This sensitivity to light and atmosphere imbues his work with a palpable mood, typically one of peace and serenity. Unlike the sublime drama found in some Hudson River School paintings, Hart favored quiet, pastoral scenes – rolling hills, meandering streams, peaceful woodlands, and cultivated fields – often suggesting a harmonious relationship between humanity and the natural world. His realism was thus tempered by a romantic sensibility, creating landscapes that felt both specific and poetically evocative.

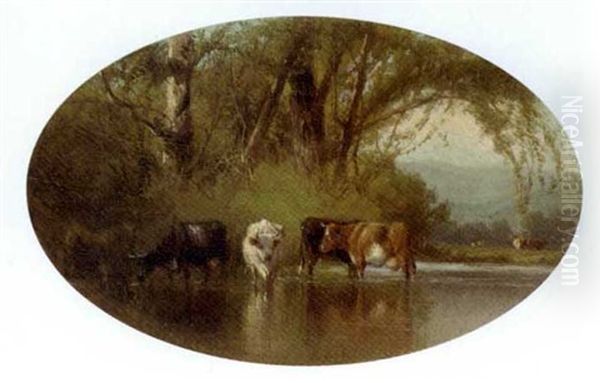

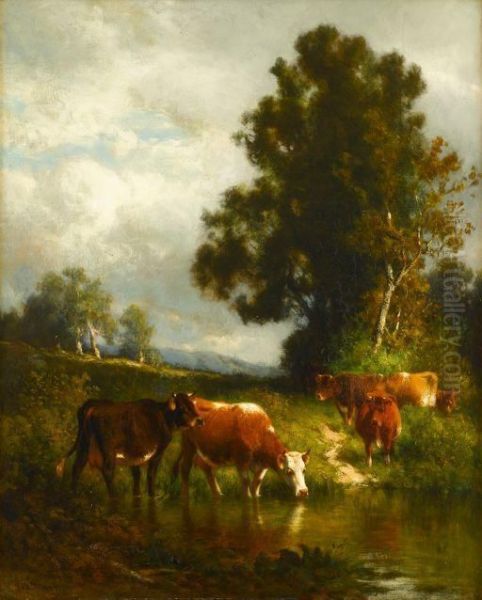

The Significance of Cattle in Hart's Work

A recurring and defining motif in William M. Hart's oeuvre is the presence of cattle. These animals are not mere incidental details; they are often central compositional elements, rendered with the same care and attention as the surrounding landscape. His frequent depiction of cows grazing peacefully in sunlit pastures or wading in cool streams became a signature feature, earning him recognition as a leading cattle painter of his time. This focus was shared with his brother, James McDougal Hart, and reflected a broader interest in pastoral themes within the Hudson River School.

The inclusion of cattle carried symbolic weight. They represented domesticity, agrarian life, and the taming of the wilderness into productive, harmonious farmland – a comforting vision for a rapidly industrializing nation. Hart reportedly undertook detailed studies of bovine anatomy and behavior, striving to capture their forms and postures with accuracy. Some critics noted a potential influence from European animal painters, such as the German artist Heinrich von Zügel (perhaps the "Voltz" mentioned confusingly in some sources) or the Barbizon painters like Constant Troyon, who also elevated pastoral scenes with animals. Regardless of specific influence, Hart's cattle are integral to the peaceful, idyllic mood that permeates much of his work, contributing significantly to his popular appeal.

Representative Works and Notable Subjects

Among William M. Hart's most celebrated works is his painting of the New London, Connecticut lighthouse. Praised for its brilliant depiction of light and clear weather, it stands as a fine example of his ability to combine precise representation with atmospheric effect. The painting captures a sense of coastal serenity and navigational safety, rendered with his characteristic clarity and luminous quality.

Hart was also proficient in etching, creating detailed prints that translated his landscape vision into a different medium. His etching Naponoc Scenery is considered one of his signature works in this field, showcasing his skill in line work and tonal variation to evoke the textures and light of the landscape. Napanoch, located near the Shawangunk Mountains in New York, was a favored sketching ground for him.

His work reached a wide audience through publications like Picturesque America (edited by the poet William Cullen Bryant), a highly popular two-volume set published in the 1870s that featured engravings based on paintings and drawings by numerous American artists. Hart's contributions helped disseminate idealized images of the American landscape across the country, shaping popular perceptions of national scenery. His subjects frequently included the tranquil landscapes of New England, the pastoral areas around Albany, and the scenic beauty of the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains, always rendered with his signature blend of realism and gentle light.

Professional Life and Contributions to Art Institutions

Beyond his personal artistic output, William M. Hart played an active and influential role in the burgeoning art institutions of New York City and Brooklyn. After establishing his studio in New York City in the early 1850s, he quickly integrated into the professional art community. His talent was recognized by his peers, leading to his election as an Associate of the prestigious National Academy of Design in 1854 (or 1855) and a full Academician in 1858. Membership in the NAD was a mark of high professional standing, and Hart regularly exhibited his works in its influential annual exhibitions from 1848 onwards.

Hart demonstrated a strong commitment to promoting specific mediums and fostering artistic education. He was instrumental in founding the American Watercolor Society (initially the American Society of Painters in Water Colors) in 1866, recognizing the need for an organization dedicated to this often-undervalued medium. He served as its president for three terms, from 1870 to 1873, championing watercolor painting in America. Furthermore, he held a significant leadership position in Brooklyn, serving as the first president (or Dean) of the Brooklyn Academy of Design and the Brooklyn Art Association, where he also delivered lectures on art principles. His exhibition record extended beyond New York, including shows at the Brooklyn Art Association (1861-1883) and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia (intermittently between 1854 and 1868).

Collaborations, Contemporaries, and Influence

William M. Hart's artistic journey was intertwined with that of his younger brother, James McDougal Hart (1828-1901). James also became a successful Hudson River School painter, known, like William, for his pastoral landscapes and skilled depiction of cattle. They shared studio space for a time and their styles bear similarities, though William is often noted for a slightly softer, more atmospheric touch. Their shared Scottish heritage and artistic focus created a strong familial bond within the New York art scene.

Hart also played a role as a mentor. The notable landscape painter Homer Dodge Martin (1836-1897), known for his later Tonalist works, studied briefly with Hart in the early stages of his career in Albany. While Martin's style eventually diverged significantly, this early connection highlights Hart's standing within the artistic community. Hart worked alongside other major figures of the era, navigating an art world that included not only the established Hudson River School painters like Kensett and Gifford but also emerging figures like George Inness, who was beginning to explore influences from the French Barbizon School, signaling a shift away from the detailed realism of the earlier Hudson River School towards more subjective, Tonalist approaches.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

William M. Hart continued to paint throughout his later years, remaining dedicated to his vision of the American landscape even as artistic tastes began to shift towards Impressionism and Tonalism. While the detailed realism of the Hudson River School gradually fell out of favor with the avant-garde towards the end of the 19th century, Hart's work retained a degree of popularity, appreciated for its technical skill and serene beauty. He maintained his presence in the New York art world, though perhaps less prominently than in his peak years.

He passed away on June 17, 1894, in New York City (some sources say Mount Vernon, NY, a close suburb), at the age of 71. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be valued for its contribution to the Hudson River School and its sensitive portrayal of the American pastoral landscape. His legacy lies in his mastery of light and detail, his focus on the tranquil aspects of nature, his popularization of cattle painting within the American tradition, and his significant contributions to the organizational life of the American art world through the National Academy of Design, the American Watercolor Society, and the Brooklyn Academy of Design.

Today, William M. Hart's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, ensuring his continued recognition. His works can be found at institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (though not explicitly listed in the source, it's a likely holder), the New-York Historical Society, the National Academy of Design in New York; the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; the High Museum of Art in Atlanta; the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York, among others.

Conclusion: A Gentle Vision of America

William M. Hart occupies a respected place within the rich tapestry of 19th-century American art. As a key member of the Hudson River School's second generation, he developed a distinctive voice, focusing on the gentle, pastoral beauty of the American landscape rather than its untamed wilderness. His meticulous attention to detail, inherited from the tradition of Asher B. Durand, combined with a masterful handling of soft light and atmosphere, created scenes of enduring tranquility and charm. His signature inclusion of carefully rendered cattle further defined his contribution, embedding his work within the agrarian ideals of the era. Through his paintings, his work in etching, his leadership in vital art organizations, and his influence on other artists, Hart helped shape the artistic vision of his time. His canvases remain a testament to a quieter, more idyllic perception of America, offering a peaceful counterpoint to the dramatic grandeur often associated with his contemporaries, and securing his legacy as a significant chronicler of the nation's pastoral heart.