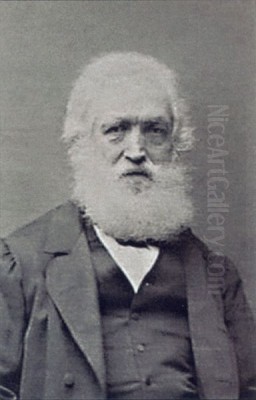

Abraham Louis Buvelot, a name inextricably linked with the evolution of Australian art, stands as a monumental figure whose contributions fundamentally reshaped the depiction of the Australian landscape. Often hailed as the "Father of Australian Landscape Painting," Buvelot's arrival in Australia marked a turning point, steering artistic representation away from purely topographical or romanticized visions towards a more naturalistic and emotionally resonant portrayal of the continent's unique environment. His work not only captured the subtle beauties of the Australian bush but also laid the crucial groundwork for the celebrated Heidelberg School, cementing his legacy as a transformative artist and mentor.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Europe

Born on March 3, 1814, in Morges, a picturesque town on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Abraham Louis Buvelot's early life was steeped in European artistic traditions. His father, Francois Simeon Buvelot, was a postal official, and his mother, Jeanne-Louise Heizer, was a teacher. This background likely provided a stable, if not overtly artistic, upbringing. Buvelot received his initial education in Lausanne, where he also began his formal art training, demonstrating an early aptitude for drawing and painting.

Seeking to further hone his skills, Buvelot, like many aspiring artists of his generation, was drawn to Paris, then the undisputed epicenter of the art world. Around 1834, he made his way to the French capital. In Paris, he had the invaluable opportunity to study under Camille Flers. Flers was a significant landscape painter and an early proponent of the Barbizon School's principles, which emphasized direct observation of nature and painting en plein air (outdoors). This mentorship was profoundly influential, instilling in Buvelot a deep appreciation for capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere, and a commitment to depicting nature with sincerity and truthfulness. The Barbizon painters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, were reacting against the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism, advocating instead for a more humble and direct engagement with the rural environment. Buvelot absorbed these ideals, which would later become central to his artistic practice in Australia.

The Brazilian Interlude

Before settling in Australia, Buvelot's journey took an extended detour to South America. In 1835, possibly due to health reasons or seeking new opportunities, he emigrated to Brazil. He initially settled in Bahia before moving to Rio de Janeiro. For eighteen years, Buvelot lived and worked in Brazil. During this period, he engaged in various artistic pursuits, including operating a photography business. Photography, a relatively new medium at the time, demanded keen observational skills and an understanding of light and composition, qualities that would undoubtedly serve his painting well.

While in Rio de Janeiro, he also gained recognition as a painter and art teacher. He received a commission from Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, which signifies a certain level of artistic standing. His time in Brazil, though less documented in terms of its direct influence on his later Australian work compared to his Parisian training, would have exposed him to a different kind of landscape, tropical light, and a diverse cultural environment. This experience likely broadened his artistic perspective and adaptability. In 1852, he returned to Switzerland, perhaps due to continued health concerns or a desire to reconnect with his European roots. He worked for a period in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Neuchâtel, where he reportedly headed an art school, further developing his pedagogical skills.

A New Beginning in Australia

In 1864, Buvelot made the life-altering decision to emigrate to Australia with his second wife, Caroline Julie Beguin. They arrived in Melbourne in February 1865, when Buvelot was already fifty-one years old – an age at which many might consider their major life changes to be behind them. However, for Buvelot, this marked the beginning of the most significant phase of his artistic career.

Upon his arrival, Buvelot initially established a photography studio in Bourke Street, Melbourne, perhaps drawing on his Brazilian experience. However, his passion lay in painting, and the venture into photography was relatively short-lived, possibly hampered by a lack of fluency in English. He soon dedicated himself entirely to painting the Australian landscape. The colonial art scene in Victoria at the time was dominated by artists like Eugene von Guérard and Nicholas Chevalier. Von Guérard, an Austrian-born artist, was known for his meticulously detailed and often sublime depictions of grand vistas, influenced by the German Romantic tradition. Chevalier, Swiss-born like Buvelot but arriving earlier, produced works that were also detailed and often catered to a taste for the picturesque. While respected, their approaches often emphasized the exotic or the monumental aspects of the landscape.

Buvelot brought a different sensibility. Armed with his Barbizon training, he sought out the quieter, more intimate aspects of the Victorian countryside. He was less interested in the grand statement and more in the subtle interplay of light and shadow, the characteristic forms of the native flora, and the atmosphere of a particular time of day. This approach was a breath of fresh air and quickly found an appreciative audience.

Artistic Style and Philosophy: Capturing the Australian Essence

Buvelot's artistic style was firmly rooted in naturalism, with a strong emphasis on plein air sketching as the basis for his studio compositions. He believed in immersing himself in the landscape, observing its nuances directly, and translating those observations with honesty. This contrasted with the prevailing studio-based practices that often relied on memory or idealized conventions.

His paintings are characterized by a gentle, lyrical quality. He had a remarkable ability to capture the unique light of Australia – the hazy glow of a summer afternoon, the cool clarity of a winter morning, or the soft light of dusk. His palette often featured muted, earthy tones, reflecting the subtle colours of the Australian bush, particularly the distinctive grey-greens of the eucalyptus trees. Buvelot was one of the first European-trained artists to truly see and depict the eucalypt not as a curious or ungainly specimen, but as an integral and beautiful element of the landscape. He rendered their gnarled trunks, drooping foliage, and dappled bark with an affectionate accuracy that resonated with local viewers.

Unlike some of his predecessors, such as John Glover, who, while innovative, sometimes Europeanized the Australian landscape, Buvelot strove for a faithful representation. His works often depicted the settled landscapes around Melbourne – farms, tracks, waterholes, and areas where human activity and nature coexisted. He found beauty in the everyday, in the pastoral scenes of rural Victoria, rather than seeking out the overtly dramatic or untamed wilderness. This focus on the familiar, rendered with such sensitivity, helped Australians to see their own environment with new eyes.

Key Themes and Subjects in His Australian Work

Buvelot's subject matter was drawn from the landscapes he encountered in Victoria. He frequently painted scenes in areas like Templestowe, Heidelberg, the Yarra Valley, and the Plenty Ranges. These regions, then on the outskirts of Melbourne, provided him with ample inspiration.

His paintings often feature water – creeks, rivers, billabongs, and waterholes – reflecting its vital importance in the Australian landscape. Cattle or sheep grazing peacefully, a solitary figure on a country road, or a simple farmhouse nestled amongst trees are common motifs. These elements imbue his landscapes with a sense of quietude and human presence, suggesting a harmonious relationship between settlers and the land.

Works like Summer Evening at Templestowe (1866) exemplify his approach. The painting captures the warm, golden light of late afternoon, with long shadows stretching across a pastoral scene. The eucalypts are rendered with characteristic fidelity, and the overall mood is one of serene beauty. Another significant work, Winter Morning Near Heidelberg (1869), showcases his ability to convey a different atmospheric quality – the crisp, cool air and softer light of a winter's day. The composition is balanced, and the details of the landscape are carefully observed.

Waterpool at Coleraine (also known as Between Tallarook and Yea or The Upper Goulburn River at Eildon) (1869) is another masterpiece, depicting a tranquil waterhole reflecting the sky and surrounding trees. The play of light on the water and the intricate rendering of the vegetation demonstrate his mastery. Wannon Falls (1872), while depicting a more dramatic natural feature, still retains Buvelot's characteristic sensitivity to atmosphere and his truthful depiction of the Australian bush.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Buvelot's oeuvre is rich with paintings that have become icons of Australian art. Summer Evening at Templestowe (1866), held by the National Gallery of Victoria, is often cited as one of his earliest masterpieces in Australia. It perfectly encapsulates his ability to capture the specific light and atmosphere of the Australian bush at a particular time of day. The warm, diffused light, the long shadows, and the carefully rendered eucalypts create a scene of tranquil, almost idyllic, rural life. It demonstrated a new way of seeing the local landscape, one that was both truthful and poetic.

Winter Morning Near Heidelberg (1869), also in the National Gallery of Victoria collection, offers a contrast in mood and season. The light is cooler, the shadows softer, and there's a sense of crispness in the air. This painting, along with others set in the Heidelberg area, helped to popularize the region as a painting ground, a legacy that would be taken up by the Heidelberg School artists.

Waterpool at Coleraine (1869), acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria, is celebrated for its depiction of a quintessential Australian scene. The still water of the billabong reflects the sky and the surrounding eucalypts, creating a composition of serene beauty. Buvelot’s meticulous attention to the textures of bark, the forms of the trees, and the quality of light is evident. This work, like many others, showed Australians the inherent beauty in their everyday surroundings.

His painting At Lilydale (1870s) showcases his skill in depicting the interplay of light filtering through the dense foliage of the bush, highlighting the textures of the tree trunks and the undergrowth. The inclusion of figures, often small and integrated into the landscape, adds a human scale without dominating the natural scene. Man with Horse and Cart (1872) is another example where human activity is part of the landscape's narrative, suggesting the pioneering spirit and the developing agricultural life of the colony.

The Mentor: Influence on the Heidelberg School

Perhaps Buvelot's most enduring legacy, beyond his own impressive body of work, was his profound influence on the next generation of Australian painters, particularly those who would form the Heidelberg School. This group, which included artists like Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, Arthur Streeton, and Charles Conder, is renowned for developing a distinctly Australian form of Impressionism.

Buvelot's studio in Melbourne became a meeting place for younger artists. They admired his commitment to plein air painting, his naturalistic approach, and his ability to capture the unique qualities of Australian light and landscape. McCubbin, in his writings, frequently acknowledged Buvelot's importance, stating, "I can remember well the enthusiasm of the students of my year for the work of Buvelot... He was a man with a profound feeling for nature... He seemed to get the poetry of Australia."

Tom Roberts, who studied in Europe and returned with knowledge of Impressionist techniques, also recognized Buvelot's foundational role. While the Heidelberg School artists would push further into Impressionistic concerns with capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light with broken brushwork, Buvelot had shown them the way by legitimizing the Australian landscape as a worthy subject and by demonstrating the importance of direct observation.

Artists like John Ford Patterson and Walter Withers were also part of this circle and benefited from Buvelot's example and, in some cases, direct encouragement. Buvelot's practice of making oil sketches outdoors, which he then used to inform his larger studio paintings, was a method adopted and adapted by these younger artists. He effectively provided them with both a technical model and an aesthetic philosophy that valued truth to nature above academic convention. His work gave them the confidence to look at their own environment and find artistic inspiration there.

Relationships with Contemporaries

While Buvelot was highly respected and influential, particularly among younger artists, his relationship with some of his established contemporaries was more complex. As mentioned, Eugene von Guérard and Nicholas Chevalier were the dominant figures in the Melbourne art scene when Buvelot arrived. Their styles, rooted in European academic traditions and often emphasizing the sublime or the picturesque, differed significantly from Buvelot's more intimate naturalism.

There is evidence of some professional rivalry, particularly with Chevalier. Art critic James Smith, a powerful voice in Melbourne at the time, championed Buvelot's work, which may have irked artists like Chevalier who represented a more established, albeit different, approach. Smith praised Buvelot for his "truthfulness" and his ability to capture the "saddened, monotonous, and sombre" aspects of the Australian bush, which he saw as its true character. This contrasted with the more romanticized or Europeanized depictions common at the time.

However, Buvelot also formed positive relationships. He became close friends with the artist Julian Ashton, who arrived in Melbourne in 1878. Ashton, who later became a significant figure in the Sydney art scene, shared Buvelot's commitment to plein air painting and naturalism. Ashton's fluency in French would have facilitated communication and camaraderie between the two artists.

Buvelot's influence extended to his participation in art societies and exhibitions. He was a member of the Victorian Academy of Arts and regularly exhibited his work, gaining critical acclaim and numerous awards. His paintings were acquired by public institutions, including the National Gallery of Victoria, which purchased Waterpool at Coleraine in 1870, a significant endorsement of his work. He also exhibited internationally, winning a gold medal at the London International Exhibition of 1872-73.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Abraham Louis Buvelot continued to paint prolifically throughout the 1870s and into the early 1880s, despite periods of ill health. His eyesight began to fail in his later years, which inevitably impacted his ability to work. He passed away in Melbourne on May 30, 1888, at the age of 74. He was buried in the Kew Cemetery, and his passing was mourned by the artistic community that he had done so much to shape.

His legacy is multifaceted. Firstly, his own paintings remain cherished for their sensitive and truthful portrayal of the Australian landscape. They offer a window into nineteenth-century Victoria and reflect a deep affection for the land. Works by Buvelot are held in major public collections across Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Secondly, his role as a catalyst for the Heidelberg School is undeniable. By breaking with earlier conventions and demonstrating a new way of seeing and depicting Australia, he paved the way for one of the most important movements in Australian art history. The artists he inspired, like Streeton, Roberts, and McCubbin, went on to create iconic images that have helped define Australia's national identity. Even artists who developed in different directions, such as the Symbolist-influenced Charles Conder or the more decorative work of later artists, operated in an artistic environment that Buvelot had helped to liberalize.

Thirdly, Buvelot contributed to a broader cultural shift in how Australians perceived their environment. At a time when the colonial gaze often sought to either tame the "alien" landscape or impose European aesthetic ideals upon it, Buvelot found beauty in its unique characteristics. He helped Australians to appreciate the subtle colours, the distinctive flora, and the particular light of their own country. This fostering of a local sensibility was a crucial step in the development of a distinctly Australian culture.

Conclusion: The Gentle Pioneer

Abraham Louis Buvelot's journey from the shores of Lake Geneva to the burgeoning colony of Victoria was one that profoundly enriched Australian art. Arriving at a mature age, he brought with him the sophisticated techniques of European naturalism, particularly the ethos of the Barbizon School, and adapted them with remarkable sensitivity to the Australian environment. He was a gentle pioneer, not one for grand, revolutionary gestures, but an artist whose quiet dedication to truth and beauty had a transformative effect.

His paintings of the Victorian bush, with their nuanced understanding of light, atmosphere, and local flora, offered a fresh and authentic vision that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to captivate audiences today. More than just a skilled painter, Buvelot was a vital mentor and inspiration, the "Father of Australian Landscape Painting" who nurtured the talents that would blossom into the Heidelberg School. His legacy is not just in the canvases he left behind, but in the enduring tradition of landscape painting that he helped to establish in Australia, a tradition that continues to explore and celebrate the continent's diverse and ever-changing environment.