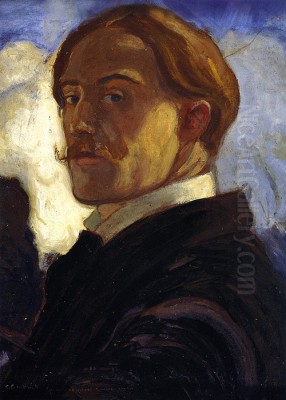

Charles Edward Conder stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the art history of both Australia and Britain. Born in England but finding his artistic voice under the Australian sun before returning to the vibrant, decadent art scenes of fin-de-siècle Europe, Conder's life and work encapsulate a unique blend of influences. He was a pivotal member of the Heidelberg School, often considered the wellspring of Australian Impressionism, yet he also carved a distinct niche for himself in London and Paris with his delicate, often whimsical paintings on silk and decorative fan designs. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, key works, and lasting legacy of Charles Conder, an artist whose delicate aesthetic bridged geographical and stylistic divides.

Early Life and Formative Years

Charles Edward Conder entered the world on October 24, 1868, in Tottenham, London. He was the third of six children born to James Conder, a civil engineer, and Mary Ann Ayres. His early childhood was marked by significant upheaval. The family relocated to India when Charles was very young, following his father's engineering work. This period was tragically cut short by the death of his mother in Bombay in 1873.

Following this loss, the young Conder was sent back to England for his education. He attended a boarding school in Eastbourne from around 1873 until 1877. Even at this early stage, his artistic inclinations were apparent. However, his father, James Conder, held conventional aspirations for his son and strongly disapproved of a career in the arts, envisioning a future for him in engineering, like himself.

This paternal opposition proved a significant obstacle. Unable to pursue formal art training in England against his father's wishes, a compromise of sorts was reached. In 1884, at the age of sixteen, Charles Conder was dispatched to the Colony of New South Wales, Australia. The plan was for him to live with his uncle, William Jacomb Conder, a land surveyor working for the New South Wales government, and train in that practical profession. This move, intended to steer him away from art, ironically placed him in an environment where his artistic talents would soon flourish.

Australia and the Dawn of Impressionism

Upon arriving in Sydney, Conder dutifully began his work with the New South Wales Lands Department. For approximately two years, he worked as a surveyor, travelling through the countryside. While the work provided him with intimate exposure to the Australian landscape, its colours, and its unique light, Conder found the profession itself tedious and unfulfilling. His artistic ambitions remained undimmed.

A turning point came around 1886 when Conder left the surveying profession and secured employment as a lithographic apprentice and illustrator for Gibbs, Shallard & Co., printers in Sydney. This position immersed him in the visual arts world, albeit commercially. More importantly, it allowed him time to pursue his passion. He began attending evening classes at the Art Society of New South Wales, studying painting under the tutelage of Alfred James Daplyn.

During this period, Conder started producing illustrations, often humorous sketches and cartoons, for publications like the Illustrated Sydney News and The Bulletin. This work honed his drawing skills and provided a modest income. Simultaneously, he began painting more seriously, initially exploring various styles but increasingly drawn to the principles of Impressionism, particularly the practice of painting en plein air (outdoors).

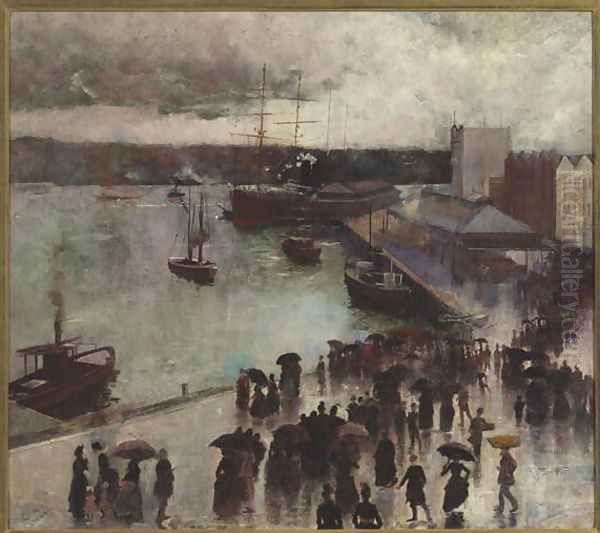

A crucial encounter occurred when Conder met Tom Roberts, an older, established artist who had recently returned from studying in Europe and was already a leading figure in promoting Impressionist ideas in Australia. Roberts became a significant mentor and friend. They painted together, notably on excursions to Coogee Beach, south of Sydney. Conder's early Australian works, such as Departure of the S.S. Orient - Circular Quay (1888), already showed his growing ability to capture the bright light and bustling atmosphere of Australian life with a fresh, modern sensibility. His work began appearing in exhibitions, including those of the Art Society of NSW, garnering attention for its distinctive charm and colour.

The Heart of the Heidelberg School

In 1888, Conder made a pivotal move from Sydney to Melbourne, the vibrant cultural capital of Australia at the time. This relocation brought him into the orbit of the artists who would form the core of the Heidelberg School. He quickly formed close bonds with Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Frederick McCubbin, the leading proponents of Australian Impressionism.

Conder shared a studio with Roberts for a time and became an integral part of their artistic circle. This group frequently painted together at artists' camps established in the rural outskirts of Melbourne, particularly at Box Hill and later Eaglemont, near the suburb of Heidelberg – the location that gave the movement its name. These camps were crucibles of creativity, where artists experimented with capturing the fleeting effects of Australian light and landscape directly from nature.

Conder fully embraced the plein air ethos. His paintings from this period, such as A Holiday at Mentone (1888) and On the River Yarra, near Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia (1890), are celebrated for their luminous palettes, evocative atmospheres, and depictions of leisurely life against the backdrop of the distinctively Australian bush or coastline. He possessed a particular talent for rendering the hazy, golden light of the Australian summer.

He was a key participant in the landmark "9 by 5 Impression Exhibition," held in Melbourne in August 1889. This exhibition, featuring small sketches painted rapidly on cigar box lids (measuring approximately 9 by 5 inches), was a bold statement of the group's Impressionist ideals and caused considerable controversy among conservative critics. Conder contributed significantly to the exhibition, showcasing his ability to capture transient effects with spontaneity and flair. Other artists involved included Roberts, Streeton, McCubbin, and figures like Louis Abrahams and John Mather. Conder's involvement cemented his position as a central figure in this defining movement of Australian art history.

Capturing the Australian Light: Style and Themes

During his Australian years (roughly 1884-1890), Charles Conder developed a style deeply rooted in Impressionist principles but imbued with his own lyrical sensibility. His primary focus was capturing the unique quality of Australian light – often harsh and bright, yet capable of producing subtle atmospheric effects, especially during sunrise, sunset, or in the dappled shade of eucalyptus trees.

His palette became noticeably lighter and brighter compared to the prevailing academic traditions. He employed broken brushwork and paid close attention to the interplay of colour and light to convey the immediacy of a scene observed outdoors. Unlike some European Impressionists who focused on urban modernity or purely optical effects, Conder, along with his Heidelberg School colleagues, often infused his landscapes with a sense of national identity and romanticism, celebrating the beauty and distinct character of the Australian environment.

Common themes in his Australian work include coastal scenes, riverside landscapes, and depictions of middle-class leisure. A Holiday at Mentone (1888) is a prime example, capturing figures relaxing on a sunny beach near Melbourne, rendered with vibrant colour and a sense of relaxed elegance. Departure of the S.S. Orient - Circular Quay (1888) showcases his ability to handle more complex, bustling scenes, capturing the energy of Sydney Harbour under bright sunlight. His landscapes, like Herrick's Blossoms (c. 1888), often possess a poetic, almost decorative quality, hinting at the aesthetic sensibilities that would become more pronounced in his later European work. He wasn't just recording light; he was evoking mood and atmosphere, often with a touch of gentle nostalgia or idyllic charm.

Return to Europe: Paris and London

Despite his success and integration into the Australian art scene, the lure of Europe, the traditional centre of the art world, remained strong for Conder. Funded partly by the sale of his painting Departure of the S.S. Orient to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, he left Australia in April 1890, bound for Paris.

Arriving in Paris, Conder enrolled at the Académie Julian, a popular independent art school frequented by international students. He studied under established academic painters like Benjamin Constant and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, though his own style continued to evolve away from strict academicism. He quickly immersed himself in the city's bohemian artistic milieu, frequenting cafes and studios in Montmartre.

His Parisian circle included fellow artists like the Canadian James Wilson Morrice and, significantly, he became acquainted with leading figures of the avant-garde. He met Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose depictions of Parisian nightlife likely resonated with Conder's own interests. He also associated with Louis Anquetin, known for his Cloisonnist style. The influence of James McNeill Whistler, particularly Whistler's aestheticism and tonal harmonies, also became increasingly apparent in Conder's work during this period.

Conder's style began to shift. While retaining an interest in light and atmosphere, his work became less focused on the direct transcription of nature associated with Impressionism. He grew increasingly interested in more imaginative, decorative, and Symbolist themes. He began experimenting with painting delicate, often Arcadian or mythological scenes, on silk, a medium that enhanced the ethereal quality of his work. This period saw the creation of works like The Moulin Rouge (1890) and A Dream in Absinthe (1890), reflecting his engagement with Parisian nightlife but rendered with a growing stylization. He also started designing and painting fans, which would become a signature aspect of his output.

Life in Fin-de-Siècle Europe

After his initial period in Paris, Conder divided his time primarily between France (Paris and Normandy) and London throughout the 1890s and early 1900s. He became a well-known figure in the artistic and literary circles of the fin de siècle, embodying the era's blend of aestheticism, decadence, and bohemianism.

In London, he associated with members of the New English Art Club and figures connected to the literary magazine The Yellow Book. His acquaintances included the writer Oscar Wilde, the poet Ernest Dowson, and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, whose elegant and often provocative linear style shared some affinities with Conder's decorative work. He also maintained a complex friendship with the artist William Rothenstein, who, despite early rivalry, became a staunch supporter and collector of Conder's work. Other artistic contacts included Walter Sickert and Augustus John.

Conder's lifestyle during this period was often precarious. He enjoyed socializing and was known for his charm, but frequently struggled financially. His personal life was also marked by challenges. During his earlier years in Australia, likely around 1888-89, he had contracted syphilis. This illness, incurable at the time, would progressively undermine his health throughout his European career, contributing to periods of instability and ultimately leading to his premature death.

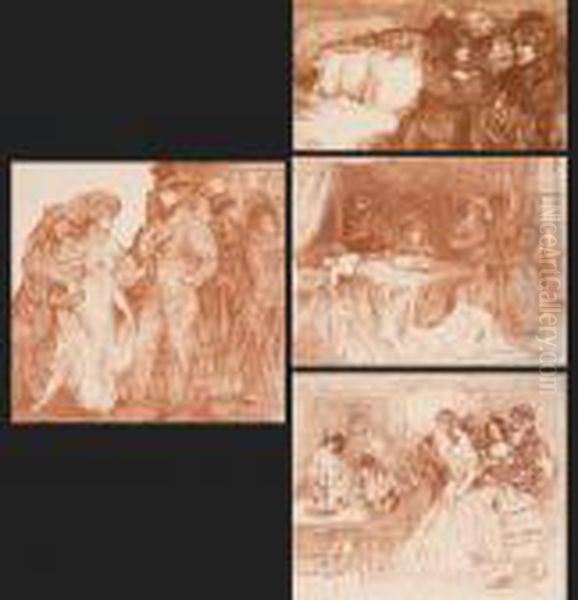

Despite these difficulties, his artistic reputation grew, particularly for his exquisite paintings on silk panels and fans. These works, often featuring elegant figures in historical or imaginary settings reminiscent of the Rococo period, appealed to collectors who appreciated their delicate beauty and escapist charm. He also produced lithographs, including a notable set illustrating scenes from Honoré de Balzac's novels, showcasing his versatility across different media.

Artistic Style Evolution: From Impressionism to Symbolism

Charles Conder's artistic journey reflects a fascinating evolution from the sun-drenched Impressionism of his Australian years to a more delicate, decorative, and Symbolist-inflected style in Europe. While the Heidelberg School fostered his engagement with plein air painting and the capture of natural light, his return to Europe exposed him to different influences that reshaped his aesthetic.

The bright, vibrant palette and relatively direct observation seen in works like A Holiday at Mentone gradually gave way to softer, more muted tones and a greater emphasis on imagination and mood. His adoption of painting on silk was crucial to this shift. The material itself lent an inherent fragility and luminosity to his work, perfectly suited to the ethereal, dreamlike quality he increasingly sought.

Influences from Whistler's tonalism and aestheticism encouraged a focus on harmonious colour arrangements and elegant composition. Furthermore, Conder developed a deep admiration for 18th-century French Rococo painters, particularly Antoine Watteau and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. He emulated their depictions of fêtes galantes – idyllic scenes of aristocratic leisure and courtship – adapting these themes into his own unique visual language. His figures often appear in period costume, inhabiting lush, imaginary landscapes or elegant interiors.

While not strictly a Symbolist painter in the manner of Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon, Conder's later work shares Symbolism's emphasis on suggestion, mood, and subjective experience over objective reality. His scenes often evoke nostalgia, melancholy, or a sense of fleeting beauty. The decorative impulse became paramount, seen not only in his fans but also in larger silk panels intended as room decorations. This blend of Rococo revival, Aestheticism, and Symbolist undertones created a distinctive style that set him apart from the mainstream trends of Post-Impressionism like Fauvism or Cubism that were emerging towards the end of his life.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Charles Conder's oeuvre includes several works that are considered landmarks of Australian art, alongside significant pieces from his European period.

From his Australian phase, A Holiday at Mentone (1888, Art Gallery of South Australia) is arguably his most famous painting. It perfectly encapsulates the Heidelberg School's interest in light, leisure, and the Australian landscape, rendered with a vibrant palette and sophisticated composition. Departure of the S.S. Orient - Circular Quay (1888, Art Gallery of New South Wales) is another crucial early work, demonstrating his ability to capture the dynamism of urban life and the brilliance of Sydney Harbour.

On the River Yarra, near Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia (1890, Art Gallery of New South Wales) represents the culmination of his plein air work in Australia, showcasing the golden light and hazy atmosphere of the Yarra Valley. The small panels from the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition (1889), though modest in scale, are historically significant as manifestos of Australian Impressionism.

His European period produced iconic works reflecting his stylistic shift. The Moulin Rouge (1890, Manchester Art Gallery) captures the famous Parisian cabaret, influenced perhaps by Toulouse-Lautrec but with Conder's own emerging decorative sensibility. A Dream in Absinthe (c. 1890, Fitzwilliam Museum) similarly explores themes of Parisian nightlife and altered states.

His paintings on silk and fan designs became his hallmark in Europe. Works like Design for a fan (1905, Victoria and Albert Museum) or numerous un-titled silk panels featuring elegant figures in Arcadian settings exemplify his mature European style – delicate, decorative, and often tinged with Rococo nostalgia. His lithographs, such as the Balzac Set (c. 1899) and individual prints like Schaunard's Studio (1904), demonstrate his skill in graphic media and his engagement with literary themes. Smoke and Chrysanthemums (1890, Manchester Art Gallery) is an example of his still life work from this transitional period.

Contemporaries and Influence

Charles Conder moved within significant artistic circles on two continents. In Australia, his primary associates were the core members of the Heidelberg School: Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Frederick McCubbin. Their collaborative plein air painting sessions and shared exhibitions were fundamental to the development of Australian Impressionism. He also interacted with other Melbourne artists like Louis Abrahams and John Mather.

Upon returning to Europe, his network expanded considerably. In Paris, his path crossed with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Louis Anquetin, key figures in the Post-Impressionist scene. The aesthetic philosophy of James McNeill Whistler exerted a profound influence on his developing style.

In London, Conder was part of a vibrant bohemian milieu that included artists and writers associated with Aestheticism and the fin de siècle. His friendships with William Rothenstein, Aubrey Beardsley, Walter Sickert, and Augustus John placed him within the currents of British art at the turn of the century. His association with literary figures like Oscar Wilde and Ernest Dowson further highlights his immersion in the era's cultural scene. While influenced by French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas indirectly through the Heidelberg School's adoption of plein air techniques, his later European work shows a stronger affinity with the decorative elegance of Whistler and the spirit of 18th-century painters like Watteau and Fragonard, rather than the structural or expressive concerns of Post-Impressionists like Cézanne, Van Gogh, or Gauguin. His work was also admired by French artists like Jacques-Émile Blanche. The auction record mentioning his work alongside Charles Francois Daubigny and Paul Drury indicates the circles in which his prints were later collected.

Later Years, Health, and Legacy

The final decade of Charles Conder's life was increasingly overshadowed by his deteriorating health. The syphilis he had contracted years earlier began to take a severe toll, leading to periods of paralysis and mental instability. Despite this, he continued to work when possible, supported emotionally and financially by friends and patrons.

In 1901, Conder married Stella Maris Belford, a wealthy Canadian widow, which provided him with some financial security. They lived primarily in London and Paris. Stella was devoted to him and cared for him during his declining health. However, his condition worsened progressively.

By 1906, he suffered a significant mental breakdown, likely tertiary syphilis affecting his brain (general paresis of the insane). He spent time in sanatoriums but experienced only temporary improvements. Charles Edward Conder died on February 9, 1909, at Holloway Sanatorium near Virginia Water, Surrey, England, at the young age of 40.

Conder's legacy is multifaceted. In Australia, he remains celebrated as a foundational figure of the Heidelberg School, instrumental in introducing Impressionist techniques and capturing the unique essence of the Australian landscape and light. His Australian works are considered national treasures. In Europe, he is remembered for his highly individual contribution to the art of the fin de siècle, particularly his delicate and decorative paintings on silk and his exquisite fan designs. He successfully bridged the gap between Australian and British art scenes, bringing a unique sensibility formed under the southern sun back to the heart of European culture. His work, though sometimes seen as escapist, possesses a distinct charm and technical finesse that continues to attract admiration.

Conder in Collections and the Market

Works by Charles Conder are held in major public collections in Australia, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. In Australia, key institutions include the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney), the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne), and the Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide). These galleries hold significant examples of his Heidelberg School paintings.

In the UK, his works can be found in the Tate Britain (London), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London, particularly strong in decorative arts like his fans), the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge), and Manchester Art Gallery, among others. These collections often feature his European paintings, works on silk, fans, and lithographs.

Conder's works appear periodically on the art market at auction houses in both Australia and the UK. While specific record prices are variable and depend on the medium, period, size, and quality of the work, his major Australian oils generally command higher prices than his later works on silk or paper, reflecting their national significance. His fans and lithographs are more accessible to collectors. Works like the lithograph Schaunard’s Studio (1904) and smaller paintings like Mythological Scene have appeared in sales, indicating ongoing collector interest. His unique position straddling Australian and British art history ensures his continued relevance in both markets.

Conclusion

Charles Edward Conder's artistic career was relatively short but remarkably impactful. From the sunlit landscapes of Australia to the sophisticated salons of London and Paris, he navigated diverse artistic currents, forging a unique path. As a key member of the Heidelberg School, he helped define a national style for Australia, capturing its light and life with unprecedented freshness. In Europe, he transformed his art, embracing decorative elegance and imaginative themes, becoming known for his exquisite paintings on silk and fans that evoked the spirit of the Rococo and the aesthetic sensibilities of the fin de siècle. Though his life was tragically cut short by illness, Conder left behind a body of work celebrated for its charm, technical skill, and its fascinating position at the crossroads of Australian and European art history. He remains a testament to the power of light, landscape, and personal vision in shaping a distinctive artistic legacy.