Abraham Weinbaum stands as a poignant figure within the vibrant, international artistic milieu of early 20th-century Paris, often referred to as the École de Paris. A Polish-Jewish artist of Ukrainian birth, his promising career, marked by a sensitive engagement with color and form, was brutally cut short by the Holocaust. His story is one of artistic dedication, cultural fusion, and ultimately, immense loss, reflecting the fate of many talented individuals whose lives and creative outputs were extinguished by the barbarity of World War II. This exploration delves into his origins, artistic development, stylistic characteristics, the environment in which he thrived, and his tragic end.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in 1890 in Kamianets-Podilskyi, a historic city in what is now Ukraine but was then part of the Russian Empire, Abraham Weinbaum's early life was shaped by his family's involvement in the textile industry. This background, while perhaps not directly artistic, may have instilled an early appreciation for materials, textures, and perhaps even patterns, elements that can subtly inform a visual artist's sensibility. However, the young Weinbaum did not find fulfillment in the commercial world.

A burgeoning dissatisfaction with what he perceived as the materialism of his surroundings in Łódź (then a major industrial city in Russian Poland, where his family had settled) spurred him to seek a different path. He moved to Odessa, a vibrant cultural port city on the Black Sea, known for its more cosmopolitan atmosphere and artistic leanings. It was here that Weinbaum began his formal studies in painting, taking the first significant steps towards an artistic career. This period in Odessa was crucial for solidifying his commitment to art, moving him away from familial expectations and towards his true calling.

Formative Years in Krakow and the Pull of Paris

Weinbaum's artistic journey then led him to Krakow, Poland. He enrolled in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, a significant center for artistic training in Central Europe. Here, he had the distinct advantage of studying under Józef Pankiewicz (1866-1940), a highly influential Polish painter and printmaker. Pankiewicz, himself deeply influenced by French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of Pierre Bonnard, played a pivotal role in introducing these modern artistic currents to Poland.

Under Pankiewicz's tutelage, Weinbaum would have been exposed to new ways of seeing and representing the world, emphasizing light, color, and subjective experience. Pankiewicz was known for encouraging his students to travel to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the time. It was during his time in Krakow that Weinbaum also reportedly encountered and befriended revolutionary Jewish youth, including the painter Joseph Leski (Józef Leski), suggesting an engagement with the intellectual and social currents of the era. The seeds of Parisian aspiration were firmly sown during this period, with Pankiewicz's influence likely being a strong catalyst.

Around 1910, Abraham Weinbaum made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. This was a common trajectory for ambitious artists from across Europe and beyond, all drawn by the city's unparalleled artistic freedom, its concentration of talent, and the avant-garde movements that were reshaping the visual arts. He arrived in a city teeming with creative energy, a melting pot of cultures and ideas.

Immersion in the École de Paris

Upon arriving in Paris, Weinbaum quickly became integrated into the artistic community, particularly the loose affiliation of artists known as the École de Paris (School of Paris). This term did not denote a formal institution or a unified stylistic movement, but rather described the diverse, largely foreign-born contingent of artists who flocked to Montparnasse and Montmartre in the early decades of the 20th century. These artists, many of whom were Jewish and had fled persecution or limited opportunities in their home countries, brought with them a rich tapestry of cultural backgrounds and artistic traditions.

Weinbaum found himself among luminaries and fellow émigrés such as Marc Chagall (from Belarus), Amedeo Modigliani (from Italy), Chaim Soutine (from Lithuania), Moïse Kisling (from Poland), Pinchus Krémègne (from Belarus), Michel Kikoïne (from Belarus), Jules Pascin (from Bulgaria), and Jacques Lipchitz (from Lithuania). This environment was one of intense creativity, mutual support, and sometimes, friendly rivalry. He would have also been aware of the towering figures of French art, such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, whose innovations were transforming the artistic landscape, as well as the more established Post-Impressionists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, whose intimate scenes and rich color palettes resonated with many.

He actively participated in the Parisian art scene, exhibiting his works in official Salons, such as the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne. These exhibitions were crucial for artists to gain visibility, critical attention, and potentially, patronage. Weinbaum's work also found appreciation beyond France, achieving notable success in Belgium, where he exhibited and sold his paintings.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Abraham Weinbaum's artistic output was characterized by its versatility in both subject matter and medium. He worked proficiently in oils, watercolors, and pencil, adapting his technique to the demands of his chosen theme. While his style evolved, it generally navigated the currents of Post-Impressionism and various strands of Modernism, often imbued with a personal, sometimes melancholic, sensibility.

His thematic concerns were diverse. He was particularly known for his still lifes (<em>natures mortes</em>), a genre with a long and rich tradition. Weinbaum's still lifes often featured flowers and fruit, subjects that allowed for an exploration of color, texture, and composition. Works like "Bouquet of Flowers" would have showcased his ability to capture the vibrancy and ephemerality of floral arrangements, perhaps with a Post-Impressionistic emphasis on subjective color and expressive brushwork.

A recurring and significant theme in his oeuvre was what is described as "natural death" or "dead flower and fruit" still lifes. These works, such as "Fleur et fruit morts" (Dead Flower and Fruit), carried a more somber, vanitas-like quality, reflecting on the transient nature of beauty and life itself. This focus suggests a contemplative, perhaps even philosophical, dimension to his art, moving beyond mere representation to evoke deeper emotional and intellectual responses. The forms in these pieces were often described as somewhat blurred, with rich colors, suggesting an interest in atmospheric effects and the emotional resonance of his subjects.

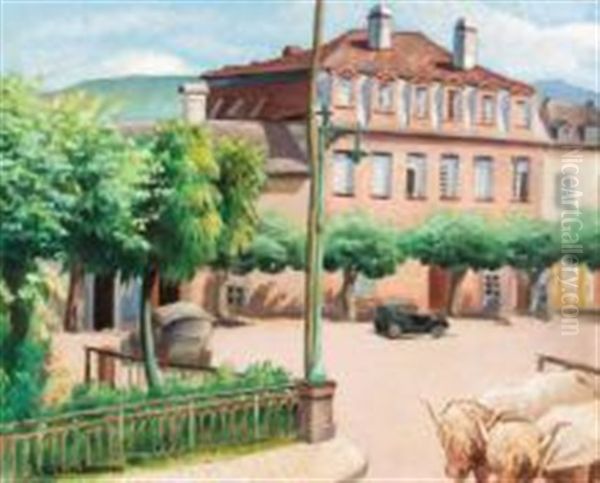

Parisian street scenes and landscapes also featured prominently in his work. Paintings like "Rue de village" (Village Street) captured the character of urban and semi-urban environments. These pieces likely reflected the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist fascination with modern life and the changing face of the city and its outskirts, rendered with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

Portraits and depictions of Jewish life were other important facets of his art. As a Jewish artist deeply embedded in a community of fellow Jewish émigrés, it is natural that he would explore themes related to his cultural heritage and identity. His portraits would have aimed to capture not just the likeness but also the character of his sitters.

Stylistically, Weinbaum's work, while rooted in observation, often leaned towards a more expressive and subjective interpretation rather than strict academic realism. His use of color was often rich and nuanced, and his brushwork could vary from delicate to more robust, depending on the subject and desired effect. There's an indication of a "graphic style" in some descriptions, which might point to a strong sense of line or a more structured compositional approach in certain pieces, perhaps contrasting with or complementing more painterly passages. He was clearly an artist who absorbed the lessons of Impressionism regarding light and color but filtered them through a more modern, personal lens, akin to many of his École de Paris contemporaries who forged individual paths rather than adhering to a single dogma.

Notable Works and Artistic Circles

While a comprehensive catalogue of his surviving works may be challenging to assemble due to the circumstances of his life and death, several titles give us insight into his preoccupations:

"Bouquet of Flowers": Exemplifying his engagement with traditional still life subjects, likely rendered with vibrant color and expressive handling.

"Fleur et fruit morts" (Dead Flower and Fruit): Indicative of his more melancholic and symbolic still lifes, exploring themes of transience.

"Rue de village" (Village Street): Representing his interest in landscape and urban scenes, capturing the atmosphere of Parisian environs.

Beyond these, his oeuvre would have included numerous other still lifes, landscapes, portraits, and scenes of Jewish life. His participation in the Salons meant his work was seen alongside a vast array of contemporary art, from the established to the avant-garde.

His connections within the École de Paris were vital. Artists like Chaim Soutine, known for his intensely expressive and often turbulent paintings, or Amedeo Modigliani, with his elegant and elongated figures, were part of this vibrant, often struggling, community. Moïse Kisling, another Polish-Jewish painter, achieved considerable success with his polished portraits and nudes. The Lithuanian-born artists Pinchus Krémègne and Michel Kikoïne, close friends of Soutine, also contributed to the expressive figurative traditions within the École de Paris. Sculptors like Jacques Lipchitz and Ossip Zadkine explored Cubist and Expressionist forms. The environment was one of shared experiences – of displacement, artistic ambition, and often, poverty – but also of immense creative cross-pollination. Weinbaum's interactions with these artists, and others like the Polish painters Eugeniusz Żak or Mela Muter, would have undoubtedly shaped his artistic perspective and practice.

The Darkening Horizon: War and Persecution

The vibrant artistic life of Paris, and Weinbaum's burgeoning career within it, was irrevocably shattered by the rise of Nazism and the outbreak of World War II. France's declaration of war on Germany in September 1939, followed by the German invasion and occupation of France in May-June 1940, marked the beginning of a terrifying era, especially for Jewish residents.

With the establishment of the collaborationist Vichy regime in the south and direct German occupation in the north, anti-Semitic laws were swiftly implemented. Jewish people were systematically stripped of their rights, their property confiscated, and their lives increasingly endangered. Many artists, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens sought refuge in the unoccupied zone or attempted to flee the country altogether.

Abraham Weinbaum, like many others, found himself in a precarious situation. Sources indicate he left Paris, perhaps initially for the unoccupied zone. One account suggests he was in Marseille, a port city that became a desperate hub for refugees trying to escape Europe. However, the net was closing.

Arrest, Internment, and Tragic Demise

In 1942 or early 1943, Abraham Weinbaum, along with his wife and daughter (some sources mention only his wife), was arrested. The exact circumstances of their capture are part of the larger, horrifying narrative of roundups and deportations of Jews from France. They were interned in French concentration camps, likely Compiègne (Royallieu) and then Drancy, located on the outskirts of Paris. Drancy served as the main transit camp for the deportation of Jews from France to extermination camps in the East.

The conditions in these camps were horrific – overcrowded, unsanitary, with inadequate food and rampant disease. They were places of fear, despair, and the constant threat of deportation. On March 23, 1943 (some sources cite March 25), Abraham Weinbaum and his family were part of Convoy No. 52, deported from Drancy to the Sobibór extermination camp in German-occupied Poland.

Sobibór was one of the Aktion Reinhard camps, established for the sole purpose of mass murder. Upon arrival, the vast majority of deportees were sent directly to the gas chambers. Abraham Weinbaum, a talented artist whose work celebrated beauty, life, and the quiet dignity of everyday objects and scenes, was murdered in Sobibór in 1943. He was 53 years old.

Legacy and Remembrance

The murder of Abraham Weinbaum in Sobibór represents an incalculable loss, not only to his family and friends but also to the broader world of art. His death, like that of millions of others during the Holocaust, silenced a unique creative voice. Much of his work was likely lost or destroyed during the war and the preceding chaos, making a full appreciation of his oeuvre challenging.

Today, Abraham Weinbaum is remembered as one of the many talented artists of the École de Paris whose careers and lives were tragically curtailed. His surviving works, when they appear in collections or at auction, serve as precious remnants of a life dedicated to art, offering glimpses into his skill, his sensibility, and the vibrant artistic world he inhabited. He is part of the "lost generation" of Jewish artists whose contributions were brutally interrupted.

Efforts to research and commemorate artists like Weinbaum are crucial. They ensure that these individuals are not forgotten and that their artistic legacies, however fragmented, are preserved and understood within the context of their times. His story underscores the profound human cost of hatred and intolerance and highlights the resilience of the artistic spirit, even in the face of unimaginable adversity. The art that does survive stands as a testament to his talent and a somber reminder of a potential that was never fully realized. His name, alongside artists like Otto Freundlich, Felix Nussbaum, Charlotte Salomon, and countless others, serves as a powerful admonition from history.

Abraham Weinbaum's journey from the textile towns of Eastern Europe to the artistic heart of Paris, his dedication to his craft, and his tragic end in an extermination camp encapsulate a significant and sorrowful chapter of 20th-century art history. His paintings, with their nuanced colors and thoughtful compositions, continue to speak of a life devoted to beauty, tragically silenced but not entirely erased.