Samuel Granowsky stands as a poignant figure in the annals of early 20th-century European art. Born into a world of transition and turmoil, his life journey took him from the vast expanses of the Russian Empire to the vibrant, bohemian heart of Paris. An artist of diverse talents and a character known for his distinctive persona, Granowsky's story is one of creative flourishing abruptly and tragically cut short by the horrors of the Holocaust. His work, though perhaps less universally known than some of his contemporaries, offers a unique window into the life of the École de Paris and the specific cultural milieu of Montparnasse.

As a painter, sculptor, and decorator, Granowsky navigated the complex artistic currents of his time. He was both an observer and a participant in the Parisian scene, capturing its energy while cultivating an image that made him a recognizable figure in the cafes and studios of the Left Bank. This account seeks to illuminate the life, artistic contributions, and enduring legacy of Samuel Granowsky, drawing upon the known details of his biography and placing him within the rich tapestry of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Samuel Granowsky entered the world in 1889, born in Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro), Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. His origins were modest; he hailed from a Jewish peasant family, a background that shaped his early experiences in a region often marked by social upheaval and anti-Semitic tensions. These formative years undoubtedly influenced his later path, contributing to the resilience and perhaps the unconventional spirit he would later display.

His artistic inclinations emerged early. Before 1901, Granowsky sought formal training at the Odessa Art School. Odessa, a cosmopolitan port city on the Black Sea, had a burgeoning cultural scene and provided a crucial stepping stone for the young artist. This initial academic grounding would provide the technical foundation upon which he would later build his more personal style.

Driven by a desire for greater artistic freedom and likely seeking refuge from the rising tide of anti-Semitism in the Russian Empire, Granowsky made the pivotal decision to leave his homeland. Around 1909, he fled Russia and made his way to France, the magnetic center of the art world at the time. Paris, with its promise of artistic liberty and its gathering of creative minds from across the globe, became his new home.

Montparnasse: The Artist and the Persona

Upon arriving in Paris, Granowsky settled in Montparnasse. This district on the Left Bank was rapidly eclipsing Montmartre as the epicenter of avant-garde and bohemian life. It was a melting pot of artists, writers, intellectuals, and models from diverse backgrounds, all drawn to its relatively affordable living costs and atmosphere of creative ferment. Granowsky quickly integrated into this vibrant community.

He found ways to support himself while pursuing his art. Sources indicate he worked as a model, notably at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a famous art school known for its open life drawing sessions that attracted many aspiring and established artists. He also reportedly worked at the legendary Café La Rotonde, a central hub in Montparnasse where artists gathered to eat, drink, debate, and exchange ideas. These experiences placed him directly at the crossroads of the Parisian art scene.

It was during this time that Granowsky cultivated his unique public image. He became known for his somewhat eccentric behavior and distinctive attire, often seen strolling through Montparnasse wearing brightly colored shirts and, most famously, a wide-brimmed Texan cowboy hat. This striking appearance earned him the affectionate nickname "the Cowboy of Montparnasse," making him a recognizable and memorable figure in the neighborhood's landscape. This persona was not merely affectation; it seemed to reflect an independent spirit and a refusal to conform entirely to conventional expectations.

Aïcha Goblet: Muse and Partner

Central to Granowsky's life in Montparnasse was his relationship with his partner and muse, Aïcha Goblet. Aïcha was a figure of note in her own right, a well-known model celebrated for her striking looks, often described as being of mixed-race heritage. Together, Granowsky and Aïcha formed a distinctive couple, embodying some of the bohemian and unconventional spirit of the era and the neighborhood.

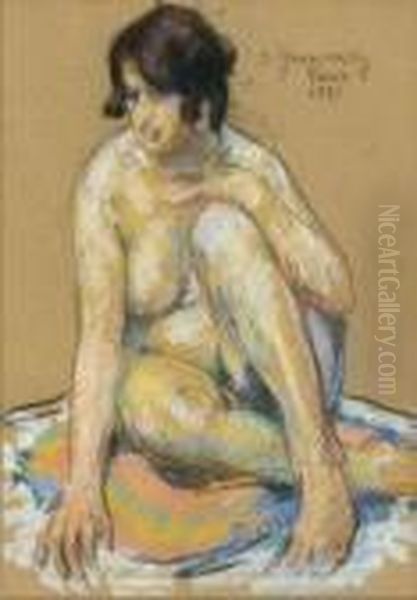

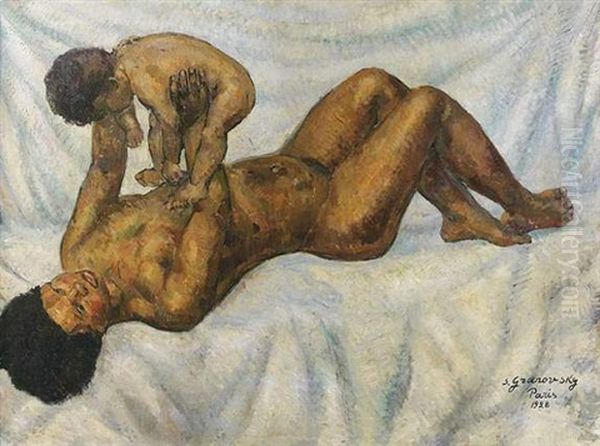

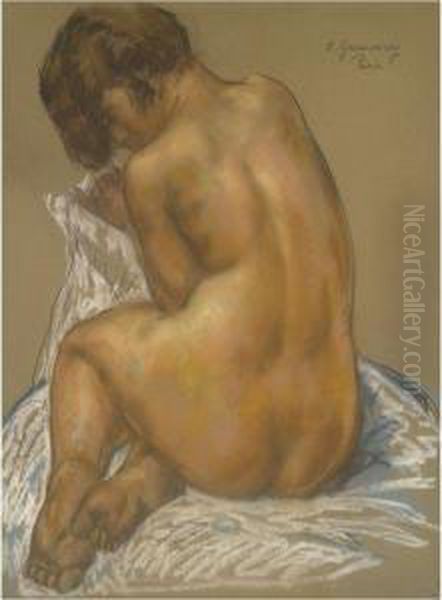

Aïcha's presence was significant not only in Granowsky's personal life but also in his art. He depicted her in numerous works, including a notable large drawing titled Nude from 1925 and likely other portraits like Aïcha (1925) and Nu au coussin rose (1921). These works capture her image and suggest her importance as an inspiration for his artistic practice.

Furthermore, Aïcha's prominence as a model connected Granowsky, at least indirectly, to a wider circle of prominent artists active in Montparnasse. She famously posed for several leading figures of the École de Paris, including Amedeo Modigliani, Tsuguharu Foujita, Moïse Kisling, and Félix Vallotton. While the available information doesn't confirm direct artistic collaborations between Granowsky and these specific painters, Aïcha's role as a shared model underscores the interconnectedness of the Montparnasse art community and places Granowsky firmly within this influential network.

Artistic Style and Themes

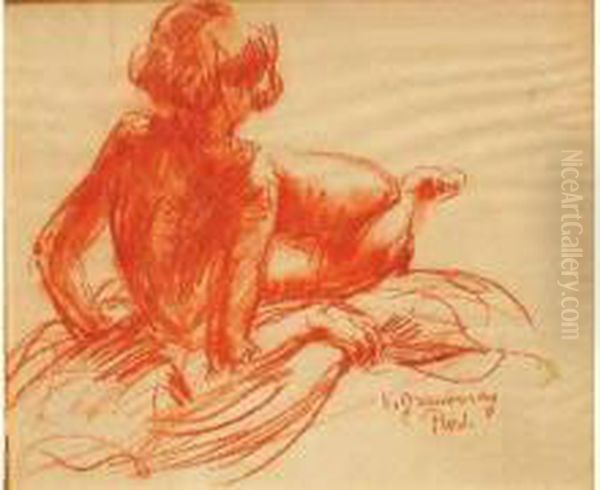

Samuel Granowsky was an artist of considerable versatility. His primary focus was painting, but his creative output extended to sculpture, murals, and decorative arts. He worked across various media, including oil paint, charcoal, and watercolor, demonstrating a command of different techniques. His training at the Odessa Art School provided him with a solid academic base, but his style evolved in the dynamic environment of Paris.

His subject matter was diverse, reflecting his life experiences and surroundings. He captured scenes of daily life in Paris, particularly the vibrant atmosphere of Montparnasse. His Russian roots also remained a significant source of inspiration, with works depicting traditional Russian figures, musicians, merchants, and folk scenes. This duality – the engagement with his immediate Parisian environment and the reflection on his cultural heritage – is a key characteristic of his oeuvre.

Granowsky also painted landscapes and portraits, including the aforementioned depictions of Aïcha and a self-portrait known as The Cowboy, which played on his public persona. Additionally, he ventured into wildlife painting, further showcasing the breadth of his artistic interests. His style, while rooted in representation, often incorporated decorative elements, particularly evident in his work on furniture and screens, blurring the lines between fine art and applied art. His approach seemed to blend observational realism with a personal, sometimes stylized, sensibility that mirrored his unique personality.

Key Works

Several specific works help illustrate Granowsky's artistic practice and thematic concerns:

Russian Musicians (1921): This significant piece, executed in oil paint on a folding screen (paravent), measures approximately 145 x 140.7 cm. Its format highlights his interest in decorative arts, while the subject matter reflects his connection to his Russian heritage. The depiction of musicians suggests an interest in cultural traditions and performance. This work is known to be held in the Nadine Nieser Collection.

Nude (Portrait of Aïcha) (1925): A large drawing measuring 79 x 61 cm (85 x 67 cm framed), this work exemplifies his skill in portraiture and life drawing. Capturing his partner Aïcha, it stands as part of a series of large nudes he created. Its existence in a private collection attests to the circulation of his work beyond public institutions.

Maternité (Motherhood) (1928): An oil painting measuring 98 x 131 cm, this work tackles a classic theme in art history. Created in Paris and signed by the artist, it likely reflects contemporary life or perhaps more universal themes of family and care. Like the Nude of Aïcha, it is noted as being in a private collection.

Nu couché (Reclining Nude) (1920): A smaller drawing (28.5 x 37 cm) depicting a female subject. Its appearance in auction records indicates the ongoing presence of Granowsky's works in the art market, allowing for their rediscovery and appreciation.

The Cowboy (Self-Portrait): While specific details like date or medium are less consistently cited in the source material, the existence of a self-portrait embracing his Montparnasse nickname is significant. It speaks to his self-awareness and perhaps a playful engagement with his public image.

These examples, spanning different formats, subjects, and periods within his Parisian career, showcase Granowsky's range and provide tangible evidence of his artistic contributions.

The Parisian Art Scene: École de Paris

To fully appreciate Samuel Granowsky's career, it's essential to understand the context of the École de Paris (School of Paris). This term doesn't refer to a single movement or style but rather to the incredible concentration of international artists, particularly non-French artists, who flocked to Paris, especially Montparnasse, during the first few decades of the 20th century. Granowsky was undeniably part of this phenomenon.

Montparnasse was the crucible where artists from Russia, Eastern Europe, Italy, Spain, Japan, Mexico, and beyond converged. Figures like Amedeo Modigliani (Italian), Chaïm Soutine (Lithuanian/Belarusian), Marc Chagall (Russian/Belarusian), Pablo Picasso (Spanish), Moïse Kisling (Polish), Tsuguharu Foujita (Japanese), Jules Pascin (Bulgarian), Jacques Lipchitz (Lithuanian), Ossip Zadkine (Belarusian), Constantin Brancusi (Romanian), and Diego Rivera (Mexican) were all active in this milieu, alongside countless others.

This international community fostered an environment of intense creativity, exchange, and sometimes rivalry. Artists experimented with various styles emerging from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism, often blending these influences with their own cultural backgrounds. Granowsky, with his Ukrainian-Jewish roots, his Russian themes, and his Parisian life, perfectly embodied the hybrid cultural identity characteristic of many École de Paris artists.

While Granowsky may not have achieved the same level of fame as Picasso or Chagall, he was an active participant in this world. His presence in the cafes, his work as a model, his relationship with Aïcha (who connected him to others like Kisling and Modigliani), and his own artistic production place him firmly within this vibrant historical context. He was one of the many talents contributing to the unique artistic ferment of Montparnasse before the outbreak of World War II.

The Shadow of War and Deportation

The rise of Nazism in Germany and the eventual outbreak of World War II cast a dark shadow over Europe, and Paris was no exception. When France fell to German forces in 1940, the situation became increasingly perilous, especially for Jewish residents, including many artists of the École de Paris. Some managed to flee, often to the United States or other safe havens.

Samuel Granowsky, however, made the fateful decision to remain in Paris. The reasons for this decision are not fully documented, but like many others, he may have underestimated the danger or lacked the means or opportunity to escape. As the Nazi occupation tightened its grip and the collaborationist Vichy regime implemented anti-Jewish laws, the risks grew exponentially.

In July 1942, during the infamous Vel' d'Hiv Roundup or shortly thereafter, French police, acting under German orders, conducted mass arrests of Jews in Paris. Samuel Granowsky was among those apprehended. He was initially interned at the Drancy transit camp, a bleak holding facility on the outskirts of Paris that served as the main deportation hub for French Jews.

From Drancy, Granowsky was deported eastward. His final destination was the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp in occupied Poland. There, in the brutal machinery of the Holocaust, Samuel Granowsky was murdered in 1942. He was 53 years old. His life, like those of millions of others, including fellow artists like Otto Freundlich and Adolphe Féder, was tragically extinguished.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Samuel Granowsky's death in Auschwitz represents an immeasurable loss – the silencing of a unique artistic voice and the destruction of a life lived between cultures. His legacy, therefore, is twofold: it resides in the body of work he managed to create during his relatively short career, and it serves as a stark reminder of the cultural devastation wrought by the Holocaust, particularly on the vibrant Jewish artistic community of the École de Paris.

In art historical terms, Granowsky is recognized for his versatile style that bridged representation, portraiture, landscape, and decorative arts. His work reflects the specific atmosphere of Montparnasse while retaining echoes of his Russian origins. He was a distinctive figure within the École de Paris, contributing to its diverse character even if he didn't belong to a major named movement like Cubism or Surrealism.

His persona as "the Cowboy of Montparnasse," coupled with his relationship with Aïcha Goblet, adds a layer of bohemian legend to his story, making him a memorable character within the social history of the era. His works continue to appear on the art market, suggesting a sustained interest among collectors and scholars. Pieces like Russian Musicians and his portraits of Aïcha are valued for their artistic merit and historical resonance.

Ultimately, Samuel Granowsky's significance lies in his embodiment of the international spirit of the École de Paris, his diverse artistic output, and the tragic circumstances of his death. He represents both the creative flourishing possible in the melting pot of early 20th-century Paris and the profound vulnerability of artists, particularly Jewish artists, during one of history's darkest chapters. His surviving works are testaments to a talent that deserved more time to mature and create.

Conclusion

The story of Samuel Granowsky is one of artistic pursuit set against a backdrop of profound historical change and ultimately, catastrophe. From his beginnings in Ukraine to his vibrant life as "the Cowboy of Montparnasse," he navigated the exhilarating and challenging world of the Parisian art scene. His diverse works – paintings, drawings, decorative pieces – reflect his unique perspective, blending observations of Parisian life with memories of his Russian heritage.

His connection to Aïcha Goblet and the broader network of artists like Modigliani, Kisling, and Foujita places him at the heart of a legendary artistic era. Yet, his narrative is irrevocably marked by the tragedy of the Holocaust, which cut short his life and career. Samuel Granowsky's legacy endures through his surviving art, offering glimpses into his talent and the world he inhabited, while his fate serves as a somber reminder of the human cost of hatred and war. He remains a significant, if perhaps underappreciated, figure of the École de Paris, whose life and work merit continued attention and remembrance.