Anita Rée stands as a poignant and significant figure in early 20th-century German modernism, an artist whose distinctive style navigated the currents of Impressionism, Cubism, and New Objectivity. Born into a complex cultural milieu and tragically cut short at the precipice of a dark era in German history, her life and work offer a compelling lens through which to view the artistic and social upheavals of her time. Her journey from Hamburg to Paris, and later to the sun-drenched landscapes of Positano, Italy, charts a fascinating artistic evolution, marked by sensitive portraiture, evocative landscapes, and a profound, often melancholic, introspection.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Hamburg

Anita Clara Rée was born on February 9, 1885, in Hamburg, Germany, into an assimilated Jewish merchant family. Her father, Israel Rée, was a prosperous importer of goods from India, and her mother, Clara, née Hahn, had South American-Venezuelan roots. This mixed heritage, with its blend of European Jewish tradition and a more distant, perhaps more exotic, maternal lineage, may have contributed to the nuanced sense of identity that would later permeate her work. Though of Jewish descent, Anita and her sister Emilie were baptized and raised in the Protestant faith, a common practice among assimilated Jewish families in Germany seeking integration into mainstream society.

From a young age, Rée displayed a clear artistic inclination. However, pursuing art as a profession was not a straightforward path for a woman of her social standing at the turn of the century. Despite her family's initial reservations, her talent and determination were undeniable. Around 1905, she began her artistic training under the Hamburg painter Arthur Siebelist, a respected local artist known for his plein-air painting and his departure from strict academicism. Siebelist's studio was a more liberal environment than the official art academies, which often still barred women or offered them limited access.

Under Siebelist, Rée honed her foundational skills. Her early works from this period, though still developing, began to show a keen observational power and a sensitivity to color and form. She was part of a circle of Siebelist's students, including Franz Nölken, Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann, and Gretchen Wohlwill, who would also go on to become notable figures in Hamburg's art scene. This early camaraderie provided a supportive environment for the budding artist.

Parisian Sojourn and the Embrace of Modernism

The period between 1910 and 1913 marked a crucial turning point in Rée's artistic development, largely due to her exposure to the vibrant avant-garde art scene in Paris. Like many aspiring artists of her generation, she was drawn to the French capital, then the undisputed center of the art world. During the winter of 1912-1913, she studied with several artists, most notably Fernand Léger, whose distinctive "Tubist" style, a variation of Cubism, emphasized cylindrical and geometric forms.

This Parisian experience was transformative. Rée absorbed the influences of Post-Impressionism and the nascent Cubist movement. She encountered the revolutionary works of Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to composition and emphasis on underlying geometric forms profoundly impacted her. The bold colors and expressive freedom of Fauvist painters like Henri Matisse and André Derain also left their mark, as did the fragmented perspectives of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Upon her return to Hamburg, Rée's style had visibly shifted. Her palette became lighter, her brushwork more expressive, and her compositions more daring. She began to move away from the more naturalistic tendencies of her early training, incorporating elements of French modernism into her unique visual language. This period saw her experiment with techniques like visible brushstrokes and scraping, adding texture and dynamism to her canvases.

The Hamburg Secession and Growing Recognition

Back in Hamburg, Anita Rée quickly established herself as a significant voice in the city's progressive art circles. In 1913, she participated in her first major exhibition at the Commeter gallery in Hamburg, showcasing the new direction her art had taken. Her work, particularly her portraits, began to gain critical attention for their psychological depth and modern sensibility.

A pivotal moment in her career came in 1919 when she became a founding member of the "Hamburgische Sezession" (Hamburg Secession). This artists' association, modeled after similar Secession movements in Vienna, Berlin, and Munich, aimed to break away from the conservative artistic establishment and promote contemporary art. The Hamburg Secession was an interdisciplinary group, including painters, sculptors, architects, and writers, all united by a desire for artistic innovation. Rée was an active and respected member, exhibiting regularly with the group throughout the 1920s.

Her colleagues in the Secession included artists she had known from Siebelist's school, such as Franz Nölken and Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann, as well as others like Alma del Banco and Gretchen Wohlwill. This collective provided a platform for avant-garde art in Hamburg and fostered a climate of artistic exchange. Rée's contributions were primarily in portraiture and figure painting, where she demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture not just the likeness but also the inner life of her subjects. Works from this period often feature a subtle melancholy and a focus on clear, defined forms, sometimes with a slightly elongated, stylized quality.

The Italian Interlude: Positano and New Objectivity

From 1922 to 1925, Anita Rée spent a significant period living and working in Positano, a picturesque fishing village on Italy's Amalfi Coast. This sojourn proved to be immensely productive and marked another evolution in her style, pushing her towards the emerging New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement. The clear light, vibrant colors, and dramatic landscapes of southern Italy provided new inspiration.

In Positano, Rée created numerous landscapes and figure paintings characterized by a heightened sense of realism, sharp contours, and a smooth, almost enamel-like application of paint. Her palette, while still rich, became more subdued and earthy compared to her earlier, more Impressionist-influenced works. There was a new emphasis on structure and a certain coolness or detachment in her depictions, hallmarks of the New Objectivity. This movement, which arose in Germany in the 1920s as a reaction against the emotionalism of Expressionism, favored a sober, objective representation of reality.

Her iconic painting, Weißes Bäume in Positano (White Trees in Positano, c. 1925), exemplifies this phase. The stark, pale trunks of the trees stand out against the muted greens and browns of the landscape, rendered with a precise, almost photographic clarity. Other works from this period, such as Blind Beggar in Positano, showcase her ability to combine this objective style with a deep sense of empathy for her subjects. She also painted portraits of local people, capturing their character with an unsentimental yet profound gaze. During her time in Italy, she was part of a community of international artists drawn to the region, including figures like Annemarie Hennings and Lisel Oppenrieder, who also contributed to Positano's burgeoning reputation as an artists' colony.

Mature Style: A Synthesis of Influences

By the mid-1920s, Anita Rée had forged a mature and highly individual artistic style. It was a synthesis of her diverse influences: the structural rigor learned from Cézanne and Cubism, the sensitivity to light and color from Impressionism, and the precise, objective rendering of New Objectivity. Her technique often involved a dry brush application, giving her surfaces a distinct, slightly graphic texture, particularly evident in her landscapes.

Her portraits from the late 1920s and early 1930s are among her most compelling works. She had an uncanny ability to convey the psychological state of her sitters, often imbuing them with an air of quiet contemplation or melancholy. Her Self-Portrait of 1930 is a powerful example, presenting a direct, unflinching gaze that speaks of both strength and vulnerability. The forms are simplified, the colors muted, and the mood intensely introspective. Another notable work, the Portrait of Hildegard Heise (1927), is considered a masterpiece of New Objectivity, capturing the modern woman with clarity and insight.

Rée's subject matter often revolved around the human figure, particularly women and children, but she also produced striking landscapes and still lifes. A recurring theme in her work is a sense of solitude or isolation, even in group portraits. This may reflect her own personal struggles and her position as a woman artist navigating a male-dominated art world, as well as her complex identity as an assimilated Jew in an increasingly nationalistic Germany.

Interactions and Contemporaries

Anita Rée's artistic journey was shaped by her interactions with a wide array of artists and movements. Her early tutelage under Arthur Siebelist in Hamburg placed her within a circle of local talent that included Franz Nölken, Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann, and Gretchen Wohlwill. This initial grounding was crucial before her transformative exposure to the Parisian avant-garde.

In Paris, her studies with Fernand Léger were significant, but equally important was her absorption of the broader artistic currents. The structural innovations of Paul Cézanne were a lasting influence, as were the color experiments of Henri Matisse and André Derain. The Cubism of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque also informed her understanding of form and space. While not a Cubist herself, elements of its deconstructive approach can be seen in the way she simplified and structured her compositions.

Back in Germany, her involvement with the Hamburg Secession connected her with the city's leading modernists. Beyond her immediate circle, the broader German art scene was dominated by Expressionism, with groups like Die Brücke (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff) and Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Gabriele Münter). While Rée's style was generally more restrained and objective than that of the Expressionists, she shared their commitment to forging a new artistic language. Her contemporary, Paula Modersohn-Becker, who died young in 1907, had earlier pioneered a path for women artists in Germany with her intensely personal and modern figurative work.

As Rée's style evolved towards New Objectivity, she found herself aligned with artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Christian Schad, who were known for their often bitingly satirical or coolly detached depictions of Weimar society. Max Beckmann, another towering figure of German modernism, also explored themes of alienation and societal critique, though with a more allegorical and symbolic approach. Rée's version of New Objectivity was perhaps less overtly political than that of Dix or Grosz, focusing more on individual psychology and the quiet poetry of everyday life, yet it shared the movement's clarity of vision and unsentimental approach. Her teacher, Max Liebermann, a leading figure of German Impressionism, represented an older generation, but his support for younger, more modern artists was significant in fostering a progressive artistic climate.

In Positano, the community of expatriate artists provided a different kind of interaction, one perhaps more focused on shared experience and the inspiration of the Italian landscape than on specific stylistic debates. Artists like Annemarie Hennings and Lisel Oppenrieder were part of this international milieu.

The Darkening Years and Tragic End

Despite her artistic achievements and growing reputation, Anita Rée's later years were overshadowed by personal difficulties and the increasingly hostile political climate in Germany. The rise of the Nazi Party in the late 1920s and early 1930s brought with it a virulent wave of antisemitism and a campaign against modern art, which was denigrated as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst).

As an artist of Jewish descent and a practitioner of modernism, Rée found herself doubly targeted. She faced increasing professional isolation and public attacks from conservative and right-wing circles in Hamburg. Commissions dried up, and she experienced profound disillusionment and depression. The vibrant cultural atmosphere of the Weimar Republic, which had nurtured her career, was rapidly disintegrating.

In 1932, Rée left Hamburg and sought refuge on the island of Sylt, hoping to find peace and continue her work. However, the political situation in Germany continued to worsen. After the Nazis seized power in January 1933, the persecution of Jews and political opponents intensified. For Rée, already struggling with depression and a sense of alienation, the future looked bleak. Despite an attempt to find solace by joining a new church, her mental state deteriorated. On December 12, 1933, at the age of just 48, Anita Rée took her own life on Sylt. Her death was a tragic loss for German art, a silencing of a unique and sensitive voice on the cusp of one of history's darkest chapters.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For many years after her death, Anita Rée's work fell into relative obscurity, a fate shared by many artists whose careers were disrupted or destroyed by the Nazi regime. However, in the post-war period, there has been a gradual rediscovery and re-evaluation of her contribution to German modernism. Exhibitions and scholarly research have brought her art back into the public eye, highlighting her unique position between different artistic movements and her sensitive portrayal of the human condition.

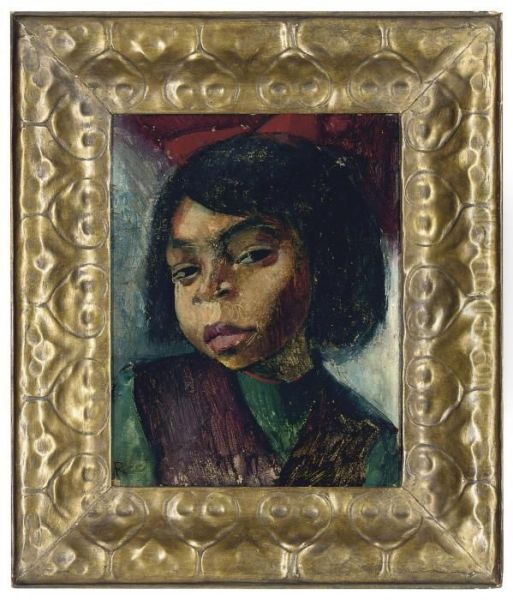

Her paintings, such as the aforementioned Self-Portrait (1930), Weißes Bäume in Positano, Blind Beggar in Positano, and the Portrait of Hildegard Heise, are now recognized as important examples of early 20th-century German art. Her early works, like Self-Portrait in Hittfeld and Portrait of a Young Girl, show the foundations of her talent. Her ability to blend emotional depth with formal clarity gives her work an enduring power.

Rée's art speaks to themes of identity, belonging, and alienation, issues that were deeply personal for her but also resonate with broader human experience. Her life story, marked by artistic dedication and tragic circumstances, serves as a reminder of the devastating impact of political intolerance on individual lives and cultural heritage.

Collections and Market Presence

Today, Anita Rée's works are held in several important public collections in Germany. The Hamburger Kunsthalle, the leading art museum in her native city, has a significant collection of her paintings, including key works like The Family, which became a highlight of its New Objectivity collection after its acquisition. The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg also holds examples of her art. Another institution with her works is the Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Many of Rée's works also reside in private collections. The exact number in private hands is difficult to ascertain, but pieces such as Anita I, Agnes, Kranker Ana (Sick Ana), Chinese Junger (Young Chinese Man), and Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child) have been noted in private ownership.

Her paintings occasionally appear at auction, where they have achieved respectable prices, reflecting her growing posthumous recognition. For instance, a Self-Portrait sold at Hauswedel in 1959 for 9,000 German Marks. More recently, another Self-Portrait fetched €129,126 at Beurrett and Bailly in Basel in June 2012, approximately three times its estimate, indicating a strong market interest. These auction results underscore the art world's increasing appreciation for her talent and historical importance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice

Anita Rée's artistic journey was one of constant exploration and refinement. From her early Impressionistic leanings to her engagement with Cubist principles and her mature embrace of New Objectivity, she forged a style that was both deeply personal and reflective of the artistic currents of her time. Her portraits reveal a profound psychological insight, while her landscapes capture a unique sense of place and atmosphere.

Though her life was tragically cut short, Anita Rée left behind a body of work that continues to speak to contemporary audiences. Her art is a testament to her resilience, her dedication to her craft, and her sensitive engagement with the world around her. As an artist who navigated the complexities of gender, heritage, and artistic innovation in a turbulent era, Anita Rée remains a compelling and important figure in the narrative of modern art. Her rediscovery is a vital act of reclaiming a voice that was unjustly silenced, allowing her luminous talent to shine once more.