Achille Beltrame stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Italian illustration and painting, renowned primarily for his decades-long contribution to the popular weekly magazine La Domenica del Corriere. His work provides an unparalleled visual chronicle of Italian life, news, and history spanning from the late 19th century through the tumultuous years leading up to the end of World War II. Combining keen observation with dramatic flair, Beltrame captured the essence of his time for millions of readers, becoming a household name and leaving behind a vast and invaluable artistic legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

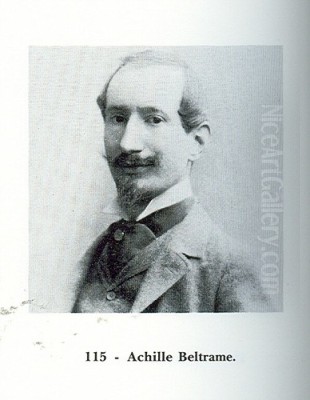

Achille Beltrame was born in 1871 in Arzignano, a town located in the province of Vicenza within the Veneto region of northern Italy. His initial education took place in Vicenza, but his artistic inclinations soon led him to Milan, the burgeoning cultural and industrial heart of the nation. At the young age of 15, he relocated to Milan to pursue formal art training.

His destination was the prestigious Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti Brera), a cornerstone of artistic education in Italy. There, he had the significant opportunity to study under Giuseppe Bertini (1825-1898), a prominent painter known for his historical subjects and his influential role as an educator. Bertini's guidance likely instilled in Beltrame a strong foundation in academic drawing and painting techniques, emphasizing realism and compositional structure, which would underpin his later illustrative work.

Beltrame's talent was recognized early on. In 1891, while still a student, he participated in the Brera Triennale, a major exhibition showcasing contemporary art. His participation alongside other emerging artists marked his entry into the Milanese art scene. During this period, his work, possibly including pieces titled "Praeludium" and referencing the legacy of sculptors like Antonio Canova (though Canova himself lived much earlier, the influence or thematic connection might have been present), earned him the Gavazzi prize, further validating his skills and potential. This early success hinted at the prolific career that lay ahead.

The Voice of La Domenica del Corriere

Beltrame's name became inextricably linked with La Domenica del Corriere, the Sunday supplement of the Milan-based newspaper Corriere della Sera. Starting formally around 1899, Beltrame embarked on a remarkable collaboration that would last until 1944, spanning over four decades. He became the magazine's principal cover artist, responsible for creating the vibrant, full-page color illustrations that graced both the front and back covers.

La Domenica del Corriere was immensely popular, reaching a wide audience across Italy. Beltrame's illustrations were arguably the magazine's most defining feature. Week after week, he translated current events, social trends, and human-interest stories into compelling visual narratives. His covers were not mere decorations; they were pictorial headlines, often depicting dramatic moments with an immediacy that captivated readers.

His output was prodigious. Over his tenure, Beltrame is credited with creating over 4,600 illustrations for the magazine. This consistent stream of work made his style instantly recognizable and cemented his status as a visual commentator on Italian life. His ability to synthesize complex events into a single, striking image was unparalleled. He worked alongside other artists at the magazine, including collaborators like Salvatore Walterino and Riccardo Salvadori, contributing to the overall visual identity of the publication, but it was Beltrame's work that became truly iconic.

A Canvas of Italian Life

The subject matter of Beltrame's illustrations for La Domenica del Corriere was extraordinarily diverse, reflecting the broad scope of the magazine itself. He effectively created a visual encyclopedia of Italy during a period of profound transformation – from the consolidation of the unified nation through industrialization, social change, political upheaval, and two World Wars.

His illustrations covered major news events, both domestic and international. He depicted natural disasters, technological advancements (like the advent of automobiles and airplanes), scientific discoveries, and moments of national celebration or mourning. Social customs, fashion trends, sporting events, and explorations also found their way onto his covers, offering glimpses into the everyday lives and aspirations of Italians.

Beltrame possessed a unique talent for capturing the human element within larger events. Whether illustrating a state ceremony, a battlefield scene, or a simple street vignette, he focused on the actions, expressions, and interactions of the people involved. This humanistic approach made his illustrations relatable and emotionally resonant, contributing significantly to their popular appeal. He documented history as it unfolded, providing a week-by-week visual record accessible to the masses.

Chronicler of Conflict

War and conflict were recurring themes in Beltrame's work, reflecting the turbulent times in which he lived. He illustrated key moments from Italy's colonial ventures, the Italo-Turkish War, and, most significantly, the First and Second World Wars. His depictions of battle scenes, military life, and the impact of war on civilians were powerful and widely circulated.

During World War I, his 1915 illustrations highlighting the heroic deeds of Italian Alpine soldiers (Alpini) fighting in treacherous mountain conditions became particularly well-known, contributing to the national narrative of sacrifice and bravery. He also visualized critical international events that shaped the era, such as his famous 1914 illustration depicting the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, the event that triggered the Great War. Another notable work captured the patriotic fervor surrounding Italy's acquisition of Trieste, visualized in his 1919 piece, The Tricolour over Trieste.

In World War II, Beltrame continued his work, producing nearly 300 illustrations related to the conflict. These images covered various fronts and aspects of the war effort. While some sources note that, like many illustrators working from reports rather than firsthand experience, his depictions might occasionally contain inaccuracies in specific details, their overall compositional strength, dramatic use of color, and narrative power remain undeniable. His 1940 illustration, War in the Indian Ocean, depicting naval combat between British and Italian forces, exemplifies his ability to convey the scale and intensity of modern warfare. Interestingly, 35 of his WWII illustrations have found a new audience through their use in the digital card game KARDS.

Beyond the Newsstand: Painting and Travel

While Beltrame achieved greatest fame through his illustrations, he also maintained a practice as a painter. His training at the Brera Academy equipped him with skills in traditional painting techniques, including oil and watercolor, alongside drawing mediums like pencil. Throughout his career, he created works beyond his magazine commissions, exploring different themes and formats.

Some sources indicate he produced paintings with classical historical and religious subjects, aligning with more traditional academic expectations. He also participated in various art exhibitions, showcasing these paintings and potentially other works to the art world establishment, separate from his popular illustrative output. This suggests a desire to be recognized not just as an illustrator but as a fine artist in a broader sense.

His artistic interests also extended to travel. Beltrame documented his experiences abroad through his art. Notable examples include paintings created during a trip to Tunis, such as Market in Tunis and Bab-Sonika Square. These works likely allowed him to explore different palettes, light conditions, and subject matter, capturing the atmosphere and daily life of North Africa with the same keen eye for detail and human activity seen in his Italian illustrations. Furthermore, starting in 1896, he undertook work for the prominent music publishing house Casa Ricordi, illustrating scores, librettos, and materials for amateur theatrical productions, demonstrating his versatility.

Artistic Style: Realism, Drama, and Imagination

Achille Beltrame's artistic style was a distinctive blend of realism and romantic drama, perfectly suited to the medium of popular illustration. His grounding in the academic tradition provided a solid foundation of realistic depiction, evident in his attention to anatomical accuracy, perspective, and detail. However, he elevated this realism with a strong sense of narrative and emotional intensity often associated with Romanticism.

Color was a key element of his work, especially in the covers for La Domenica del Corriere. He used vibrant hues to capture attention and convey mood, employing bold contrasts and dynamic compositions to heighten the drama of the scenes depicted. His style was influenced by various currents, including potentially the lively, anecdotal approach of the Neapolitan school of painting and what some sources refer to as the "Domenicali" style – likely referring to the specific aesthetic developed for the Sunday magazine itself, emphasizing clarity, impact, and storytelling.

A remarkable aspect of Beltrame's skill was his ability to visualize events and locations he had never personally witnessed. Working from news reports, photographs, and his own imagination, he reconstructed scenes with convincing detail and atmosphere. This required not only technical proficiency but also a powerful imaginative capacity. His illustrations were thus a fusion of reportage and artistic interpretation, aiming to convey the essence and emotional weight of an event rather than merely a literal transcription. He worked proficiently in oil, watercolor, and pencil, adapting his technique to the needs of each commission.

Beltrame in Context: Contemporaries and Movements

To fully appreciate Achille Beltrame's contribution, it's useful to place him within the context of Italian art at the turn of the 20th century. His career unfolded during a period of diverse artistic exploration in Italy. While Beltrame focused on narrative illustration rooted in realism, other artists were pursuing different paths.

His teacher, Giuseppe Bertini, represented the established academic tradition, often focused on historical or allegorical subjects. Beltrame adapted this tradition for a modern, mass audience. In Milan, where Beltrame worked, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of Divisionism, an Italian response to Neo-Impressionism, practiced by artists like Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, and Angelo Morbelli. These painters explored light and color through fragmented brushstrokes, often tackling social themes (like Emilio Longoni) or symbolic landscapes, differing significantly from Beltrame's clear, narrative style.

The preceding generation's Macchiaioli movement, with key figures like Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini, had already championed realism and painting outdoors, focusing on scenes of contemporary Italian life and landscape, providing a foundation for later realist trends. Beltrame's work, while realist, served a different, journalistic function.

As Beltrame's career progressed, Futurism erupted onto the Italian art scene around 1909, led by artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla. Futurism celebrated dynamism, speed, and technology, radically breaking from traditional representation. Beltrame's work remained largely untouched by this avant-garde movement, continuing to serve his broad audience with accessible, narrative imagery.

Within the field of illustration and graphic arts, Beltrame was a leading figure. He can be considered alongside other notable Italian illustrators and poster artists of the era, such as Marcello Dudovich, known for his elegant advertising posters, or perhaps compared to the work of Eduardo Matania, an Italian-born illustrator who gained fame working for British publications. Later figures like Gino Boccasile would become known for a different style of illustration, particularly during the Fascist era. Beltrame's direct successor at La Domenica del Corriere, Walter Molino, continued the tradition of illustrative covers, though with his own distinct style. Beltrame's unique position was defined by his longevity, consistency, and deep connection to a single, highly influential publication.

Legacy: A Visual Archive of an Age

Achille Beltrame passed away in Milan on February 19, 1945, shortly before the end of World War II. He left behind an extraordinary body of work that transcends mere illustration. His decades of covers for La Domenica del Corriere constitute a unique visual archive of Italian history, society, and culture during a critical period of modernization and conflict.

His influence was immense. For millions of Italians, Beltrame's illustrations were their window onto the world, shaping their understanding and perception of current events. He possessed an uncanny ability to make history immediate and relatable. His work served as a form of visual journalism long before the widespread use of photography in print media became dominant.

Today, Beltrame's illustrations are highly valued not only for their artistic merit – their compositional skill, vibrant color, and narrative power – but also as invaluable historical documents. They offer insights into the attitudes, anxieties, and aspirations of the time. Collections of his work are studied by historians, sociologists, and art historians alike, providing a rich resource for understanding 20th-century Italy. His dedication to chronicling the life of his nation through accessible, dramatic imagery secures his place as a major figure in Italian popular culture and graphic arts.

Conclusion

Achille Beltrame was more than just a painter or an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller for an entire nation. Through his tireless work for La Domenica del Corriere, he created an enduring panorama of Italian life across nearly half a century. From the halls of the Brera Academy under Giuseppe Bertini to the weekly deadlines of a major publication, he honed a style that was both realistic and captivatingly dramatic. His depictions of historical turning points like the Sarajevo assassination, the struggles of World War I soldiers, and the vast canvas of everyday Italian experiences remain powerful testaments to his skill and vision. Beltrame's legacy is preserved in the thousands of images that not only captured the news of the day but also shaped the collective memory of an era.