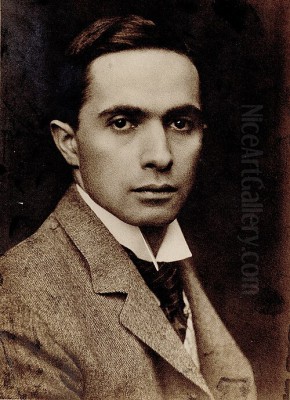

Joseph Christian Leyendecker stands as a towering figure in the history of American illustration, a master craftsman whose work not only defined the look of popular magazines for decades but also shaped the very image of American life and ideals in the early 20th century. Born in Montabaur, Germany, on March 23, 1874, Leyendecker emigrated with his family to Chicago at the age of eight. This move set the stage for an artistic journey that would see him become one of the most sought-after and influential illustrators of the American Golden Age of Illustration.

His distinctive style, characterized by bold brushwork, dramatic lighting, and idealized figures, captured the aspirations and aesthetics of a nation undergoing rapid change. From iconic advertising campaigns to a staggering number of magazine covers, Leyendecker's art became ubiquitous, leaving an indelible mark on American visual culture that resonates even today. His legacy is one of technical brilliance, commercial success, and a unique ability to translate the zeitgeist of his time into compelling visual narratives.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Leyendecker's artistic inclinations emerged early. After his family settled in Chicago in 1882, he pursued formal art training, initially apprenticing at the engraving firm of J. Manz & Company. Seeking a more robust education, he enrolled at the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Here, he honed his foundational skills, developing the discipline and technical proficiency that would underpin his later success. His younger brother, Frank Xavier Leyendecker, also pursued illustration, and the two would share a close personal and professional bond throughout their lives.

Seeking to further refine his talents and absorb European artistic traditions, J.C. Leyendecker, accompanied by his brother Frank, traveled to Paris in the mid-1890s. They enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned art school that attracted students from around the world. In Paris, Leyendecker studied under prominent academic painters like Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Paul Laurens, absorbing lessons in classical draftsmanship, anatomy, and composition. He also studied with Benjamin Constant.

The vibrant Parisian art scene exposed Leyendecker to influential contemporary movements and artists. The bold graphic style and poster art of figures like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the decorative elegance of Alphonse Mucha, and the lively compositions of Jules Chéret undoubtedly left their mark. This European sojourn provided Leyendecker with a sophisticated understanding of technique and style, blending academic rigor with modern graphic sensibilities, which he would soon synthesize into his uniquely American idiom upon his return.

The Ascent in Chicago and New York

Returning to Chicago around 1896, Leyendecker quickly began to make a name for himself. He secured his first major commission that year, creating a cover for Collier's Weekly, a prominent national magazine. This marked the beginning of a prolific career in periodical illustration. His talent was undeniable, and his work stood out for its technical polish and eye-catching designs.

Recognizing that New York City was the epicenter of the publishing and advertising industries, Leyendecker relocated there around 1900. This move proved pivotal. He established a studio, initially shared with his brother Frank, and his career rapidly gained momentum. His work soon caught the attention of George Horace Lorimer, the influential editor of The Saturday Evening Post.

Lorimer commissioned Leyendecker to create covers for the Post, initiating one of the most famous and enduring artist-magazine relationships in American history. Beginning around the turn of the century, Leyendecker would go on to paint an astonishing 322 covers for The Saturday Evening Post over the next four decades. This achievement remained unsurpassed until his own protégé, Norman Rockwell, eventually exceeded the number. Leyendecker's covers became synonymous with the magazine, defining its visual identity and contributing significantly to its massive circulation and cultural impact.

The Saturday Evening Post: A Defining Partnership

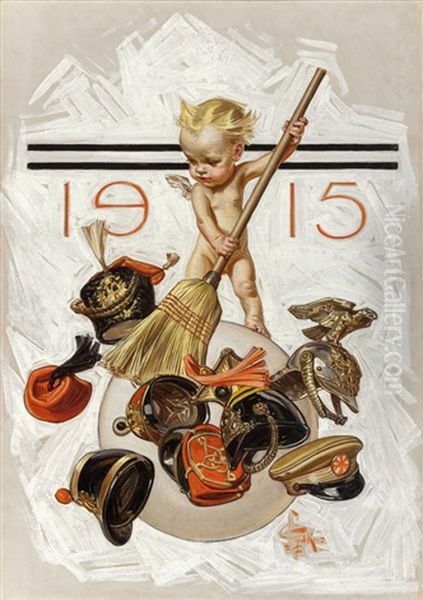

Leyendecker's tenure at The Saturday Evening Post cemented his status as a household name. His covers were not mere decorations; they were keenly observed commentaries on American life, celebrations of holidays, and reflections of national moods. He developed recurring themes and iconic images that became eagerly anticipated by the public.

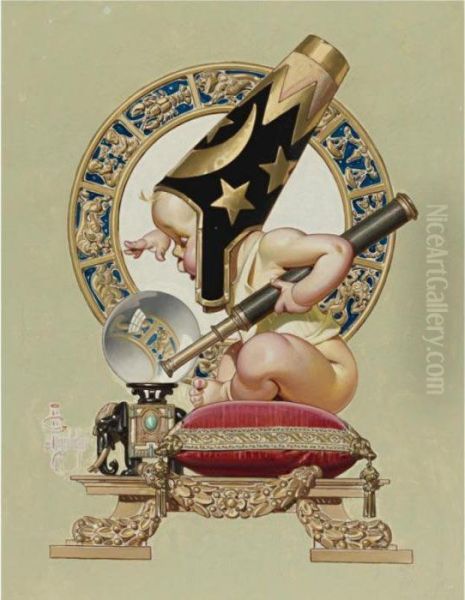

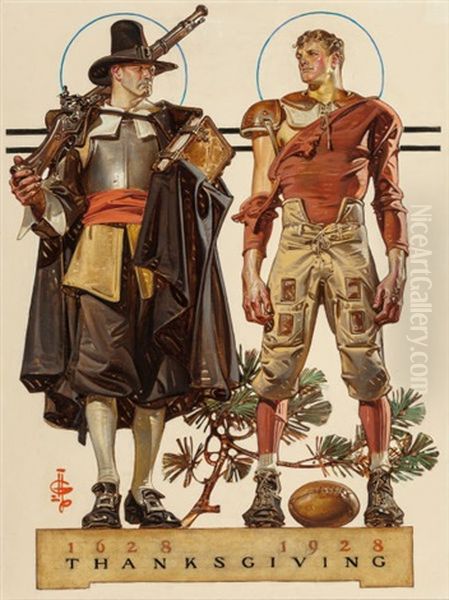

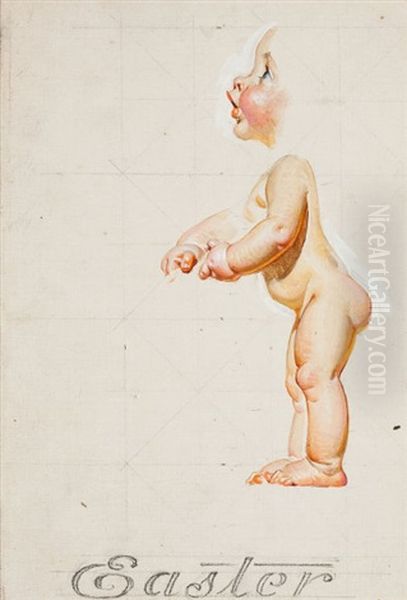

His New Year's Baby covers, featuring a cherubic infant symbolizing the fresh start of the year, became an annual tradition beloved by millions. Similarly, his depictions of Santa Claus helped solidify the modern image of the jolly, red-suited figure in American popular culture. He captured the spirit of holidays like Thanksgiving, often with images of pilgrims or bountiful feasts, and the Fourth of July, with patriotic scenes and historical figures.

Beyond holidays, Leyendecker's Post covers depicted a wide range of subjects: collegiate life, sporting events, romantic encounters, and everyday moments imbued with elegance and charm. His ability to convey narrative and emotion through expressive figures and dynamic compositions made each cover a miniature masterpiece. His style, characterized by visible, confident brushstrokes and a masterful use of light and shadow, was instantly recognizable and widely admired. He set a high bar for magazine illustration, influencing countless artists who followed.

The Arrow Collar Man: Crafting an Ideal

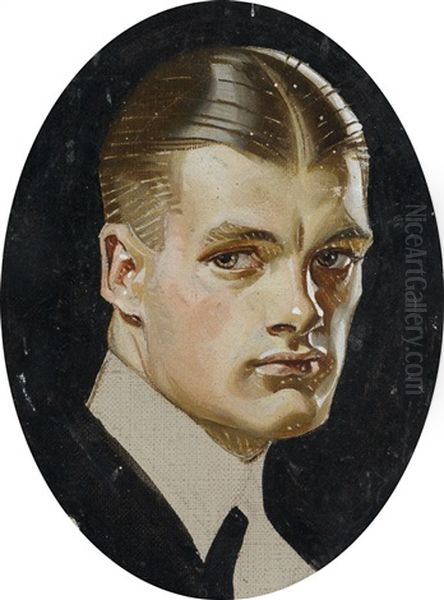

Perhaps Leyendecker's most iconic creation outside of his Post covers was the "Arrow Collar Man." Beginning in 1905, Leyendecker was commissioned by Cluett, Peabody & Co. to create advertising illustrations for their Arrow brand of detachable shirt collars and, later, shirts. The resulting campaign was a phenomenon.

Leyendecker depicted handsome, sophisticated, and impeccably dressed young men, embodying an ideal of masculine grace, confidence, and style. These figures, often modeled by Leyendecker's life partner Charles Beach, became national heartthrobs. The "Arrow Collar Man" wasn't just selling collars; he was selling an aspirational lifestyle, an image of the modern American man.

The advertisements were immensely popular, reportedly generating thousands of fan letters addressed to the fictional ideal. The Arrow Collar Man became a cultural touchstone, influencing fashion trends and setting a standard for male elegance in the early 20th century. Leyendecker's artistic skill elevated mere advertising into a form of popular art, demonstrating the power of illustration to shape perceptions and desires. This campaign remains a landmark in advertising history, showcasing Leyendecker's unparalleled ability to create compelling and enduring brand imagery. His depiction rivaled the earlier "Gibson Girl" created by Charles Dana Gibson in terms of cultural impact.

Master of Advertising and Commerce

While the Arrow Collar campaign was his most famous advertising work, Leyendecker's talents were sought by numerous other major companies. His illustrations graced advertisements for a wide array of products, demonstrating his versatility and commercial appeal. He brought his signature style and technical prowess to campaigns for brands like Kellogg's, illustrating wholesome images for their breakfast cereals, including Corn Flakes and potentially baby food lines.

He created sophisticated advertisements for Interwoven Socks, showcasing the product with the same elegance he brought to fashion illustration. His work extended even to heavy industry, with notable illustrations produced for companies like Krupp Steel, where he managed to imbue industrial subjects with a sense of power and precision. He also created posters during both World War I and World War II, contributing his artistic talents to the war effort by creating compelling patriotic imagery designed to boost morale, encourage enlistment, and promote war bonds.

Leyendecker's success in advertising stemmed from his ability to create images that were not only beautiful but also persuasive. He understood how to capture attention, evoke emotion, and associate products with desirable qualities like sophistication, modernity, and reliability. His work significantly raised the artistic standards of American advertising, proving that commercial art could be both effective and aesthetically refined. He operated in an era alongside other great illustrators who also navigated the commercial world, such as Maxfield Parrish, whose luminous paintings also found their way into advertising and print.

Signature Style and Technique

J.C. Leyendecker's artistic style is instantly recognizable, marked by a unique blend of academic draftsmanship and bold, painterly execution. One of his most distinctive technical features was his brushwork. He often employed visible, decisive strokes, sometimes using a cross-hatching technique with oil paint that lent texture and vibrancy to his surfaces. This technique, combined with areas of smoother rendering, created a dynamic interplay of textures.

His handling of light and shadow was dramatic and sophisticated, influenced perhaps by his classical training but employed for modern graphic impact. He used light to sculpt form, define planes, and create focal points, often bathing his subjects in a warm, inviting glow or using sharp contrasts to heighten drama. His figures possessed a tangible solidity and weight, grounded in a strong understanding of anatomy learned under masters like Bouguereau and Laurens.

Compositionally, Leyendecker favored strong diagonals, dynamic poses, and carefully cropped framing to create visual interest and narrative tension. Even in static portraits, his figures often convey a sense of impending movement or contained energy. He was a master of capturing expression, able to convey subtle nuances of emotion – confidence, contemplation, joy, or gentle humor – through facial features and body language. His color palettes were typically rich and harmonious, contributing to the overall appeal and mood of his illustrations. This technical facility allowed him to work across various genres, from idealized portraits to humorous vignettes, always maintaining his signature elegance.

Cultural Touchstones: Shaping American Holidays

Beyond the sheer volume of his work, Leyendecker's lasting impact lies significantly in his contribution to the visual iconography of American holidays. Through his Saturday Evening Post covers, he helped create and popularize images that are now deeply ingrained in the national consciousness.

His New Year's Baby, first appearing on a Post cover in 1906, became an enduring symbol of renewal and hope. Each year, readers looked forward to seeing the latest depiction of the cherubic infant, often shown interacting with the symbols of the departing year. This single recurring image cemented Leyendecker's role as a shaper of popular traditions.

Similarly, while not the sole inventor of the modern Santa Claus image, Leyendecker's numerous depictions of a plump, jolly, red-clad Santa for the Post were hugely influential in standardizing the character's appearance for generations of Americans. He portrayed Santa not just as a mythical figure, but often as a warm, human character interacting with children or engaged in festive activities.

His Thanksgiving covers often featured idealized scenes of Pilgrims or families gathered for the feast, reinforcing themes of history, gratitude, and abundance associated with the holiday. For the Fourth of July, he created patriotic tableaus, sometimes featuring historical figures or symbols like the Liberty Bell, capturing the nation's celebratory spirit. Through these widely circulated images, Leyendecker didn't just illustrate holidays; he helped define how Americans visualized and celebrated them.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping Future Illustrators

J.C. Leyendecker's influence extended far beyond his own lifetime and the pages of the magazines he graced. He was a dominant force during the Golden Age of Illustration, a period that also included luminaries like Howard Pyle, known for his adventure illustrations and influential teaching, and Pyle's student N.C. Wyeth, famous for his dramatic book illustrations. Leyendecker's commercial success and artistic distinctiveness set him apart.

His most direct and acknowledged protégé was Norman Rockwell. Rockwell, who began his own legendary career at The Saturday Evening Post while Leyendecker was still its reigning star, openly admired Leyendecker and considered him a mentor. Rockwell's early work, in particular, shows a clear stylistic debt to Leyendecker's bold brushwork and idealized figures, though Rockwell would eventually develop his own distinct, more narrative and less stylized approach.

Beyond Rockwell, Leyendecker's sophisticated technique, his ability to blend commercial appeal with artistic integrity, and his sheer productivity inspired generations of illustrators. His approach to composition, lighting, and figure work became part of the visual language taught in art schools and adopted by commercial artists. Even later illustrators working in different styles, such as Coby Whitmore or Al Parker, operated in a field whose standards and possibilities had been significantly shaped by Leyendecker's pioneering work. His creation of aspirational figures like the Arrow Collar Man also influenced the broader field of fashion illustration and advertising art. James Montgomery Flagg, another contemporary famous for his "I Want You" Uncle Sam poster, also worked extensively in advertising and portraiture, sharing the era's vibrant illustration scene.

Personal Life: Privacy, Partnership, and Prejudice

Despite his immense public fame as an illustrator, J.C. Leyendecker maintained a relatively private personal life. Central to his life was his relationship with Charles A. Beach. Beach, initially hired as a model, became Leyendecker's lifelong companion, business manager, and the primary model for the iconic Arrow Collar Man. Their partnership lasted for nearly five decades, from the early 1900s until Leyendecker's death.

They lived and worked together, first in New York City and later in a large estate Leyendecker purchased in New Rochelle, New York, which they shared with J.C.'s brother Frank and sister Augusta. Leyendecker was homosexual, and his relationship with Beach was an open secret within their social circle but not something discussed publicly in the context of the era's social mores. Some scholars suggest homoerotic undertones can be subtly detected in some of his depictions of idealized male figures, particularly in the Arrow Collar ads featuring Beach.

The intense nature of their partnership, however, reportedly led to increasing isolation in Leyendecker's later years. Beach managed Leyendecker's affairs tightly, and the artist became known for being somewhat reclusive. The social constraints and potential prejudice surrounding same-sex relationships at the time likely contributed to Leyendecker's preference for privacy. His brother Frank, also an artist and reportedly homosexual, struggled with personal issues and died relatively young in 1924, deeply affecting J.C.

Later Years and Diminished Fame

The 1930s brought significant changes for Leyendecker. The Great Depression impacted the advertising industry, leading to fewer lucrative commissions. While he continued his work for The Saturday Evening Post, tastes began to shift. The highly idealized, elegant style that had defined the Roaring Twenties started to seem less relevant in an era marked by economic hardship.

Furthermore, the star of Norman Rockwell was rising rapidly at the Post. Rockwell's detailed, narrative-driven, and often more relatable depictions of everyday American life gained immense popularity, gradually eclipsing Leyendecker's more stylized approach. Though Leyendecker continued to produce covers until 1943, his frequency decreased, and Rockwell became the magazine's dominant cover artist.

Financial pressures mounted, forcing Leyendecker to downsize significantly. He had to sell his grand New Rochelle estate and dismiss most of his household staff. He and Charles Beach moved into a smaller home on the property. His final years were marked by relative seclusion, though he continued to work, taking on commissions for war bonds posters and other projects. He passed away from a heart attack at his home in New Rochelle on July 25, 1951, at the age of 77. Charles Beach, his companion for nearly half a century, died shortly thereafter. His estate was primarily inherited by Beach and his sister Augusta.

Rediscovery and Enduring Appeal

For a period after his death, J.C. Leyendecker's fame somewhat faded, overshadowed by the enduring popularity of Norman Rockwell and the shift towards photography in magazine illustration. However, his immense contribution to American art and culture was never entirely forgotten, particularly among illustration historians, artists, and collectors.

In recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in Leyendecker's work. Museums and galleries have mounted exhibitions dedicated to his art, reintroducing his stunning paintings and drawings to new audiences. The National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, holds a substantial collection and has played a role in promoting his legacy. His work has been featured in major shows exploring the Golden Age of Illustration.

Scholarly attention has also increased, with books and articles analyzing his technique, his impact on advertising and popular culture, and the context of his personal life. His unique style, technical mastery, and the sheer beauty of his images continue to captivate viewers. The iconic status of the Arrow Collar Man, the New Year's Baby, and his Santa Claus depictions ensures his place in American cultural history. His work serves as a vibrant window into the aesthetics and aspirations of the early 20th century.

Market Value and Collections

The renewed appreciation for J.C. Leyendecker's work is reflected in the art market, where his original paintings command significant prices. Major auction houses like Christie's and Heritage Auctions regularly feature his work, with important pieces selling for hundreds of thousands, and occasionally millions, of dollars. For instance, a study for a Collier's cover titled "Applying the Finishing Touch" was estimated at $150,000-$250,000 at a Christie's auction in 2014. One of his most famous Saturday Evening Post cover paintings, variously known as "Beat-Up Boy," "Truant," or "Boy Reading Dime Novel" (originally published May 21, 1910), reportedly sold for over $4 million, highlighting the peak value of his most iconic works.

While original paintings are highly valued, reproductions and vintage advertisements featuring his art are also popular collectibles, accessible at various price points on platforms like eBay. This indicates a broad base of appreciation for his imagery.

Significant collections of Leyendecker's original work are held by public institutions. The Haggin Museum in Stockton, California, boasts one of the largest public collections of Leyendecker originals, including paintings, studies, and sketches by both J.C. and his brother Frank. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York also holds works related to Leyendecker, contextualizing him within American art history. Galleries specializing in American illustration, such as Illustration House in New York, frequently handle and exhibit his work, contributing to its visibility and market presence. These collections ensure that Leyendecker's artistic contributions are preserved and remain accessible for study and appreciation.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was more than just an illustrator; he was a visual architect of early 20th-century America. His prolific output, technical brilliance, and keen sense of style left an indelible mark on popular culture, advertising, and the very identity of American illustration. From the sophisticated Arrow Collar Man to the beloved New Year's Baby, his creations became iconic, reflecting and shaping the aspirations of a nation.

His partnership with The Saturday Evening Post defined the look of the magazine for generations and set a standard for cover art that influenced countless successors, including his famed protégé Norman Rockwell. While his fame waned in later life, the enduring power and beauty of his work have ensured his rediscovery and cemented his place as a pivotal figure in American art history. Leyendecker's legacy lives on in the museums that house his work, the collections that cherish his originals, and the enduring appeal of the timeless images he crafted. He remains a testament to the power of illustration to capture the spirit of an age and create lasting cultural icons.