Benjamin Rabier (1864–1939) stands as a monumental figure in the annals of French art, celebrated for his enchanting illustrations, witty caricatures, and pioneering contributions to the nascent field of animation. His prolific career, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, left an indelible mark on popular culture, particularly through his masterful and humorous depictions of animals. Rabier's unique ability to imbue creatures with human-like expressions and personalities resonated deeply with the public, establishing a style that would influence generations of artists, including such luminaries as Walt Disney and Hergé. This exploration delves into the life, work, artistic style, collaborations, and enduring legacy of this remarkable French artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on December 30, 1864, in La Roche-sur-Yon, Vendée, France, Benjamin Rabier's early life set the stage for a career that would be deeply rooted in French culture and artistic traditions. While detailed accounts of his formative years are not extensively documented in common art historical surveys, it is understood that he spent his life and developed his craft primarily within France. His artistic inclinations likely emerged early, nurtured by the vibrant visual culture of the era, which included burgeoning print media, satirical journals, and the early stirrings of commercial art.

Unlike many artists who receive formal academic training, Rabier's path seems to have been more self-driven, honing his skills through observation and practice. He entered the professional sphere not initially as a full-time artist but reportedly worked as a bookkeeper. This practical employment provided him with stability while he pursued his passion for drawing, contributing illustrations to various Parisian magazines and newspapers from the 1890s onwards. This period was crucial for developing his distinctive line work and his keen eye for capturing humorous situations, often involving animals.

The Ascent of an Illustrator: Defining a Signature Style

Benjamin Rabier's breakthrough into the public consciousness came through his work as an illustrator for popular French periodicals. He contributed to satirical magazines like Le Rire and L'Assiette au Beurre, which were known for their sharp social commentary and high-quality graphic art. It was in these venues that Rabier began to specialize in animal drawings, a niche that he would come to dominate. His contemporaries in French illustration and caricature included artists like Caran d'Ache (Emmanuel Poiré), known for his "stories without words," and Théophile Steinlen, famed for his Art Nouveau posters, including "Le Chat Noir," which also featured animals prominently.

Rabier's style was characterized by its clean lines, dynamic compositions, and an unparalleled ability to convey emotion and narrative through animal subjects. He did not merely draw animals; he created characters. His creatures were often anthropomorphized, displaying a range of human foibles, joys, and sorrows, which made them instantly relatable and amusing. This approach distinguished him from more purely naturalistic animal illustrators. His work was accessible, unpretentious, and possessed a universal appeal that transcended age and social class.

Mastery in Animal Anthropomorphism

The cornerstone of Rabier's artistic genius was his profound understanding and portrayal of animal anthropomorphism. He possessed an uncanny ability to observe animal behavior and translate it into expressive, often comical, human-like actions and emotions without losing the essential "animalness" of his subjects. This was a delicate balance that few artists achieve with such consistency and charm. His animals were not simply humans in animal suits; they retained their distinct animal characteristics while engaging in human-like scenarios.

This skill was evident in his numerous book illustrations, comic strips, and advertising work. He could make a duck look perplexed, a dog appear cunning, or a cat seem disdainful, all with a few deft strokes of his pen. This approach was not entirely new; artists like Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville in the earlier 19th century had famously created satirical works featuring animals in human roles. However, Rabier brought a lighter, more playful, and distinctly modern sensibility to the genre, aligning with the burgeoning mass media and advertising industries of his time.

Iconic Creations: La Vache Qui Rit (The Laughing Cow)

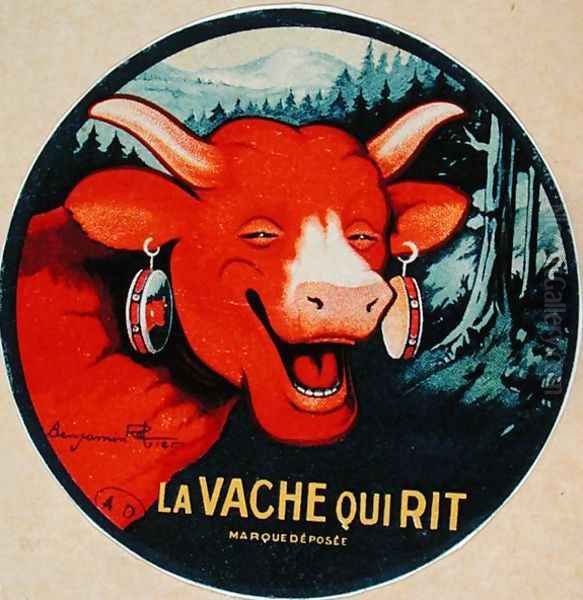

Perhaps Benjamin Rabier's most globally recognized creation is the image of "La Vache qui rit" (The Laughing Cow). This cheerful, red cow, adorned with cheese-box earrings (which themselves depict the laughing cow, creating a Droste effect), became the iconic logo for the processed cheese brand of the same name. The story behind its creation is intertwined with World War I. Rabier had designed a laughing cow emblem for military meat supply trucks, humorously nicknamed "La Wachkyrie," a pun on Wagner's Valkyrie.

After the war, cheese-maker Léon Bel sought a striking image for his new processed cheese product. He acquired the rights to Rabier's laughing cow design in 1921. Rabier subsequently refined the image, making it red and adding the signature earrings at Bel's suggestion. The logo was an instant success, its vibrant color and infectious mirth making it one of the most enduring and recognizable brand mascots in history. This single design demonstrates Rabier's acumen in creating memorable and commercially potent imagery, a skill shared by other artists who successfully bridged the gap between fine art and commercial design, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec with his posters.

Illustrating La Fontaine's Fables: A Career Pinnacle

A significant achievement in Rabier's oeuvre was his complete set of illustrations for Jean de La Fontaine's Fables. Published in 1906 by Jules Tallandier, this work is often considered a high point of his career. La Fontaine's Fables, a cornerstone of French literature, had been illustrated by many esteemed artists before Rabier, including Gustave Doré and Jean-Baptiste Oudry. Rabier's interpretation, however, brought a fresh, humorous, and accessible perspective to these classic moral tales.

His illustrations for the Fables perfectly showcased his talent for animal characterization. Each animal, from the cunning fox to the proud lion and the naive crow, was rendered with expressive detail and a touch of gentle satire. Rabier's visual storytelling enhanced the narratives, making the fables engaging for a new generation of readers, particularly children. His clear, bold lines were well-suited for reproduction, and the humor he injected made the moral lessons more palatable and memorable. This project solidified his reputation as France's foremost animal illustrator.

Pioneering Animation: Collaborations and Innovations

Beyond his prolific work in print, Benjamin Rabier was a significant, if sometimes overlooked, pioneer in the nascent field of animation. He ventured into this new medium in the 1910s, a period when animation was still in its experimental stages. His most notable collaborator in this domain was Émile Cohl, another foundational figure in animation history, often credited as "the father of the animated cartoon" for works like Fantasmagorie (1908).

Rabier and Cohl collaborated on a series of animated shorts starting around 1916, most famously featuring Rabier's popular dog character, Flambeau (often translated as "Torch" or "Warhorse"). Titles included Les Aventures de Flambeau and Flambeau, chien de guerre. Rabier typically provided the character designs and storyboards, leveraging his established style, while Cohl, with his greater technical experience in animation, handled the animation process. Their partnership, though reportedly fraught with some financial and artistic disagreements, produced some of the earliest character-driven animated series.

Rabier also worked with other figures in the early film industry. He collaborated with René Navarre, an actor and producer famous for playing Fantômas in Louis Feuillade's film serials. Together, they worked on an animated adaptation of Louis Forton's comic strip Les Pieds Nickelés. These early animated works, while perhaps not as technically fluid as those of later American pioneers like Winsor McCay (Gertie the Dinosaur) or J. Stuart Blackton, were crucial in establishing animation as a storytelling medium in France and showcased Rabier's ability to translate his static characters into moving images. His work in animation, like that of Georges Méliès in live-action trick films, demonstrated the French avant-garde's early embrace of cinema's potential.

The Gédéon Series: Enduring Children's Literature

Another significant part of Benjamin Rabier's legacy is the Gédéon series of children's books. Gédéon, an adventurous and resourceful duck (sometimes described as a goose), became one of Rabier's most beloved characters. Starting in the 1920s, Rabier wrote and illustrated numerous Gédéon adventures, published in a distinctive large-format album style. These books, such as Gédéon s'en va-t-en guerre and Gédéon mécano, followed the intrepid duck through various escapades, often involving ingenious contraptions and encounters with a host of other animal characters.

The Gédéon books were immensely popular and are considered classics of French children's literature. They exemplify Rabier's storytelling prowess, combining gentle humor, exciting plots, and his trademark charming animal illustrations. The success of Gédéon further cemented Rabier's status as a master of children's entertainment, creating a character that, much like Beatrix Potter's Peter Rabbit in England, captured the imaginations of young readers. The narrative style, often featuring sequential panels, also prefigured elements of the modern comic book or bande dessinée.

Artistic Style and Techniques Revisited

Benjamin Rabier's artistic style is immediately recognizable. His primary medium was ink drawing, often colored for print. His line work was confident and economical, using a ligne claire (clear line) approach that would later be famously adopted by artists like Hergé, the creator of Tintin. This clarity made his drawings highly legible and effective for reproduction in newspapers, books, and advertisements.

He had a remarkable ability to simplify forms while retaining expressiveness. His animals, though anthropomorphized, were anatomically plausible in their basic structure, which lent them a sense of believability despite their often-outlandish predicaments. Rabier's use of humor was central; it was rarely biting or cruel, but rather gentle, observational, and situational. He excelled at visual gags and conveying narrative through purely visual means, a skill honed in his contributions to wordless comic strips. His compositions were dynamic, often using diagonal lines and varied perspectives to create a sense of movement and energy.

Influence on Contemporaries and Successors

The impact of Benjamin Rabier's work on subsequent generations of illustrators, cartoonists, and animators is substantial. In France, his influence can be seen in the development of the bande dessinée tradition. Artists like Edmond-François Calvo, known for his animal-centric comics like La Bête est Morte!, show stylistic and thematic parallels with Rabier's work.

Internationally, Rabier's animal drawings and early animations are acknowledged as having an influence on Walt Disney. Disney, who spent time in France after World War I, would have been exposed to Rabier's popular illustrations and animated shorts. The expressive, anthropomorphic animals that became the hallmark of early Disney animation share a kindred spirit with Rabier's creations. The clarity of line and the emphasis on personality in characters like Mickey Mouse echo Rabier's approach.

Hergé, as mentioned, also cited Rabier as an influence, particularly for his clean drawing style and his way of depicting animals. This lineage highlights Rabier's role as a bridge figure, connecting 19th-century caricature traditions with 20th-century comic art and animation. Even later comic artists, such as Albert Uderzo of Asterix fame, or André Franquin, creator of Spirou and Marsupilami, worked within a Franco-Belgian comic tradition that Rabier helped to shape, particularly in its humorous and character-driven aspects.

Commercial Ventures and Wider Impact

Rabier was a commercially successful artist, adept at applying his talents to a wide range of applications. Beyond book illustration and magazine work, he was highly sought after for advertising. His creation of "La Vache qui rit" is the prime example, but he designed numerous other posters, packaging, and promotional materials. His ability to create appealing and memorable characters made his work ideal for branding.

He also designed postcards, toys, and other merchandise featuring his popular animal characters. This entrepreneurial spirit and understanding of mass media were characteristic of the era, where artists increasingly engaged with commercial opportunities. His work helped to popularize animal imagery in advertising and demonstrated the power of a strong, character-based visual identity. The widespread dissemination of his work through these commercial channels ensured his place in the popular visual culture of France.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Benjamin Rabier continued to work prolifically throughout his life. He passed away on October 10, 1939, in Faverolles, Indre, France, leaving behind an immense body of work. His death occurred at the cusp of World War II, an event that would dramatically reshape the world he knew. However, his artistic contributions had already secured his legacy.

Today, Benjamin Rabier is remembered as a key figure in the golden age of French illustration and a pioneer of animation. His books, particularly the Gédéon series and his La Fontaine illustrations, are still cherished and reprinted, delighting new generations. "La Vache qui rit" remains a global brand, its smiling cow a testament to Rabier's enduring design genius. Museums and galleries occasionally feature his work in exhibitions on illustration or early animation, recognizing his historical importance.

His influence extends beyond specific artists; he helped to define a certain playful, humane, and distinctly French approach to animal caricature and storytelling. He demonstrated that popular art could be both commercially successful and artistically meritorious. His ability to connect with a broad audience through humor and charm, particularly with his animal characters, remains his most significant achievement. Artists like Jean-Jacques Sempé, known for his gentle, humorous illustrations of French life, can be seen as inheritors of this tradition of witty and observant graphic art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Figure in Art History

Benjamin Rabier was more than just an illustrator of animals; he was a masterful visual storyteller, a humorist, an innovator in animation, and a shaper of popular visual culture. From the bustling pages of Parisian magazines to the flickering screens of early cinema, and from the cherished illustrations in children's books to the globally recognized face of a cheese brand, Rabier's art permeated French society and beyond.

His clean, expressive style, his genius for anthropomorphism, and his gentle humor created a body of work that remains fresh and engaging. He stands alongside other great French graphic artists like Honoré Daumier for his social observation (albeit in a lighter vein) and Albert Robida for his imaginative visual narratives. Rabier's legacy is not only in the specific characters he created but in the joy and amusement his art has brought to millions, and in the inspiration he provided to countless artists who followed in his footsteps, shaping the worlds of illustration, comics, and animation for decades to come. His work serves as a vibrant reminder of the power of art to capture the imagination and reflect the human (and animal) condition with wit and warmth.