Adam Elsheimer stands as a uniquely influential figure in the history of European art, a German painter whose brief but brilliant career, spent largely in Italy, left an indelible mark on the development of Baroque painting. Born in the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt am Main in 1578 and dying tragically young in Rome in 1610, Elsheimer mastered a distinctive style characterized by innovative treatments of light and shadow, intimate scale, and poetic interpretations of landscape. Though his surviving oeuvre is small, its impact resonated profoundly, shaping the vision of giants like Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt van Rijn.

Early Life and Formation in Frankfurt

Adam Elsheimer was baptized on March 18, 1578, in Frankfurt. He was one of ten children born to a master tailor, Anton Elsheimer. His early artistic education took place in his native city under the tutelage of Philipp Uffenbach. Uffenbach himself was a pupil of Mathis Grünewald's follower, suggesting a lineage connected to the expressive intensity of late German Gothic and Renaissance art. During this apprenticeship, likely lasting from around 1593 to 1598, Elsheimer would have absorbed the meticulous detail and graphic precision characteristic of the Northern European tradition.

Frankfurt, a bustling commercial center, also provided exposure to prints and paintings from the Netherlands. The influence of contemporary Dutch and Flemish landscape specialists, known for their developing naturalism and atmospheric effects, seems to have captured the young artist's imagination early on. This blend of German precision and Netherlandish landscape sensibility formed the foundation upon which his later Italian experiences would build.

The Journey South: Venice and the Lure of Italy

Around 1598, driven by the ambition common to many Northern artists of his generation, Elsheimer embarked on a journey to Italy, the heartland of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance. His first major stop was Venice, a city whose artistic traditions were steeped in color (colorito) and atmospheric light. Here, he encountered the works of the great Venetian masters like Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, whose dramatic compositions and rich palettes offered a stark contrast to the more linear traditions of the North.

In Venice, Elsheimer is known to have worked, possibly as an assistant, in the studio of Johann Rottenhammer, another German painter residing in the city. Rottenhammer specialized in small-scale cabinet pictures, often on copper, depicting historical and mythological subjects – a format and subject matter that Elsheimer himself would master. This collaboration was significant, placing Elsheimer within a network of expatriate artists and exposing him directly to the Italian market's taste for refined, collectible works. He also absorbed influences from earlier Venetian painters like Vittore Carpaccio, known for their narrative detail.

Rome: A New Artistic Center

By 1600, Adam Elsheimer had moved to Rome, the ultimate destination for aspiring artists across Europe. The city was undergoing a period of intense artistic ferment, energized by the Counter-Reformation and the patronage of the Church and powerful families. Here, Elsheimer quickly established himself within a vibrant international community of artists, scholars, and patrons. He became a respected, if somewhat enigmatic, figure, known for his intelligence and the unique quality of his art.

He formed crucial friendships in Rome. Most notably, he became close with the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens, who arrived in Rome the same year. Rubens deeply admired Elsheimer's work, recognizing its originality and power despite its small scale. Other important contacts included the landscape painter Paul Bril, another Fleming long resident in Rome, and Dr. Giovanni Faber, a papal physician, botanist, and member of the Accademia dei Lincei, indicating Elsheimer moved in intellectual circles interested in science and nature. He also associated with Dutch artists like Karel van Mander (who mentioned him in his `Schilder-boeck`) and Hendrick Goudt, who would later become his pupil and engraver.

In Rome, Elsheimer married Carla Antonia Stuarda (an Italianized name for Stuart) from Frankfurt in 1606. Despite his growing reputation, his meticulous and slow working method contributed to persistent financial difficulties. He produced relatively few paintings, laboring over each small copper plate with painstaking care. This perfectionism, combined with potential mismanagement of finances, led to chronic debt and, according to some accounts, a brief period of imprisonment for debt shortly before his death.

The Cabinet Picture Perfected: Style and Technique

Elsheimer's preferred medium was oil paint applied to small plates of copper. This smooth, non-absorbent surface allowed for exquisite detail, luminous color, and subtle gradations of light, creating works often described as "jewel-like." His paintings are typically small, rarely exceeding one or two feet in width, demanding close inspection by the viewer and fostering a sense of intimacy.

His subject matter drew primarily from biblical narratives, mythology, and ancient history, but he often chose less common episodes or interpreted familiar stories in novel ways. He imbued these scenes with a profound sense of atmosphere and psychological depth. Rather than focusing solely on the human figures, Elsheimer gave unprecedented importance to the landscape settings, which often dominate the composition and play a crucial role in establishing the mood.

Innovations in Light and Landscape

Adam Elsheimer's most significant contribution lies in his revolutionary handling of light and landscape. He moved beyond the idealized or formulaic landscapes common in the 16th century, striving for greater naturalism and emotional resonance. He was a pioneer in depicting specific times of day and varied atmospheric conditions, particularly twilight and night scenes.

His mastery of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and dark – was exceptional. Influenced perhaps by Caravaggio's dramatic tenebrism, which was taking Rome by storm during Elsheimer's time there, Elsheimer adapted light effects to his own poetic ends. He often employed multiple light sources within a single composition – moonlight, torchlight, firelight, divine radiance – exploring their different qualities and reflections with remarkable sensitivity. This complex illumination creates spatial depth, highlights narrative focus, and evokes powerful moods, ranging from serene contemplation to intense drama.

The Flight into Egypt: A Nocturne Milestone

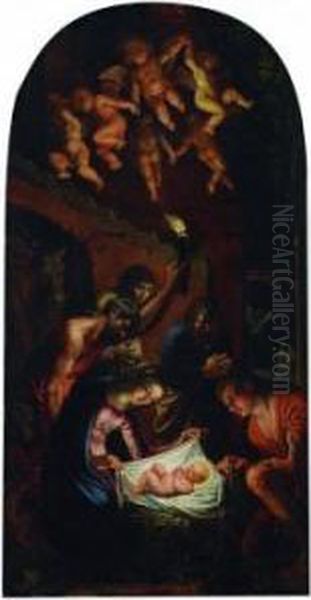

Perhaps Elsheimer's most famous work, The Flight into Egypt (1609, Alte Pinakothek, Munich), exemplifies his innovations. Painted on a small copper plate, it depicts the Holy Family resting by a riverbank beneath a vast, star-filled night sky. It is considered one of the earliest realistic depictions of the night sky in Renaissance or Baroque art. Elsheimer meticulously rendered the moon and its reflection on the water, the distinct band of the Milky Way composed of countless tiny stars, and identifiable constellations.

The painting features four distinct light sources: the moon in the sky, the campfire tended by Joseph, the torch held by the figures on the path, and the subtle reflection on the water. This complex illumination creates a scene of extraordinary tranquility and mystery. The accuracy of the celestial details has led to speculation about whether Elsheimer used a telescope, although Galileo Galilei's telescopic observations were published slightly later. Regardless, the painting demonstrates Elsheimer's keen observation of nature and his groundbreaking ability to translate the poetics of night into paint. It set a precedent for nocturnal landscapes that would influence generations of artists.

Other Representative Works

While The Flight into Egypt is iconic, Elsheimer produced other masterpieces that showcase his range and skill.

Jupiter and Mercury in the House of Philemon and Baucis (c. 1608-09, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden): This painting illustrates a story from Ovid's Metamorphoses. Elsheimer masterfully contrasts the humble, warmly lit interior where the elderly couple welcomes the disguised gods with the moonlit landscape visible through the doorway. The scene is filled with carefully observed still-life details, showcasing his Northern heritage, while the handling of light creates a sense of quiet wonder.

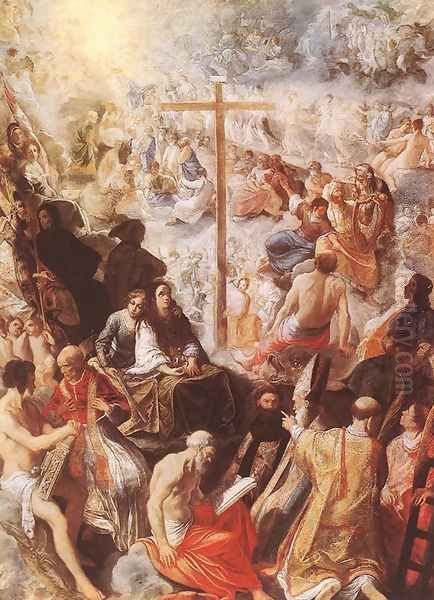

The Stoning of St. Stephen (c. 1603-04, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh): An early example of his Roman period work, this piece demonstrates his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions within a small format. The dramatic intensity of the martyrdom is heightened by the turbulent sky and expressive figures, showing an engagement with Italian narrative traditions.

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1600s, National Gallery, London): This work displays Elsheimer's skill in integrating figures into a luminous landscape setting. The light breaking through the clouds and illuminating the central figures creates a sense of divine presence within a naturalistic environment.

Tobias and the Angel (often called 'The Small Tobias', c. 1607-08, Historisches Museum Frankfurt): A recurring theme for Elsheimer, this version shows the figures walking through a richly detailed, atmospheric landscape at dusk. The subtle play of light captures the transition from day to night, enhancing the narrative's sense of journey and divine guidance.

The Good Samaritan (c. 1605, Louvre, Paris): Here, Elsheimer uses the landscape and the fading light to underscore the drama and compassion of the biblical parable. The figures are integrated into a deep, atmospheric setting that emphasizes the isolation of the wounded traveler and the kindness of the Samaritan.

Christ Crucified (1603, Alte Pinakothek, Munich): An early Roman work showing his developing command of dramatic light and emotional intensity within a religious narrative.

These works, though few in number, consistently demonstrate Elsheimer's meticulous technique, his sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and his ability to infuse traditional subjects with fresh psychological insight and poetic feeling.

Anecdotes and Character

Historical accounts suggest Elsheimer was a thoughtful and somewhat melancholic individual, dedicated to his art to the point of obsession. His slow, deliberate working process, while resulting in paintings of exceptional quality, hindered his financial success. Rubens, in a letter mourning Elsheimer's death, lamented the artist's "sin of sloth" (likely referring to his slow production rate) and the poverty that plagued him, suggesting his talent deserved greater worldly reward.

His friendship with Rubens was significant. Rubens owned several of Elsheimer's works and clearly learned from his German colleague's approach to landscape and light. The story of Rubens attempting to help Elsheimer with his debts highlights the camaraderie, but also the precarious financial reality, faced by many artists in Rome, even those with considerable talent and connections.

Elsheimer's interest in accurately depicting the natural world, as seen in the night sky of The Flight into Egypt, aligns with the growing scientific curiosity of the age, reflected in his friendship with Dr. Faber and his association with the Accademia dei Lincei. He was an artist engaged with the intellectual currents of his time, blending empirical observation with profound artistic sensibility.

Profound Influence on Baroque Painting

Despite his short life and limited output, Adam Elsheimer's influence was remarkably widespread and enduring, largely thanks to reproductive prints made after his paintings, particularly those by his pupil Hendrick Goudt. These prints circulated throughout Europe, disseminating his innovative ideas.

Peter Paul Rubens: As mentioned, Rubens was a direct admirer. Elsheimer's influence is visible in Rubens's early landscapes and history paintings, particularly in the handling of light and atmosphere, and the integration of figures into evocative settings. Rubens's own Flight into Egypt clearly pays homage to Elsheimer's version.

Rembrandt van Rijn: Elsheimer's impact on Rembrandt was profound, though likely indirect, transmitted through Rembrandt's teacher, Pieter Lastman, and possibly through Goudt's prints. Lastman and his circle of Amsterdam artists, known as the Pre-Rembrandtists (including Jan Pynas and Jacob Pynas), had absorbed Elsheimer's style during their own Italian travels or through prints. Rembrandt's early works show a clear debt to Elsheimer in their dramatic chiaroscuro, small scale, intimate narrative focus, and choice of Old Testament subjects. Elsheimer's pioneering night scenes paved the way for Rembrandt's own explorations of darkness and light.

Dutch Italianates: Elsheimer was a key figure for the first generation of Dutch painters who traveled to Italy and brought back a new style of landscape painting, characterized by warm, golden light and picturesque scenery. Artists like Cornelis van Poelenburch, Bartholomeus Breenbergh, and Leonard Bramer show his influence in their small-scale landscapes and history paintings, often on copper.

Claude Lorrain: The great French Baroque landscape painter, who spent most of his career in Rome, also learned from Elsheimer. While Claude developed his own distinct style of idealized classical landscapes, Elsheimer's sensitivity to light, particularly the effects of dawn and dusk, and his poetic rendering of nature provided an important foundation.

Other Contemporaries: Artists like Paul Bril and Jan Brueghel the Elder, established landscape painters, also seem to have responded to Elsheimer's innovations. His ability to merge figure and landscape seamlessly, and his focus on atmospheric effects, pushed landscape painting towards greater naturalism and emotional depth across Europe. His collaborators like Johann Rottenhammer also helped spread elements of his style.

Elsheimer's unique synthesis of Northern detail and Italianate light and drama created a new kind of cabinet picture – intimate yet powerful, meticulously observed yet deeply poetic. He demonstrated that small-scale works could possess the emotional weight and complexity traditionally associated with large-scale history painting.

Final Years and Untimely Death

Adam Elsheimer's final years were overshadowed by financial struggles. His meticulous process meant he could not produce works quickly enough to ensure a steady income, leading to the debts that reportedly resulted in his brief imprisonment in 1610. Friends, including Rubens, intervened to help secure his release.

However, shortly after, on December 11, 1610, Adam Elsheimer died in Rome at the age of just 32. The exact cause of his death is unknown, but the combination of financial stress, possible imprisonment, and perhaps underlying health issues likely contributed. His death was mourned by his fellow artists. Rubens wrote movingly of his grief, stating, "I have never felt my heart more profoundly pierced by grief than by this news, and I shall never regard him again with friendly eyes who has brought me such grievous tidings... In my opinion, he had no equal in small figures, in landscapes, and in many other subjects... one could have expected things from him that one has never seen before and never will see."

Legacy: The Luminous Intensity of Adam Elsheimer

Adam Elsheimer occupies a pivotal position in art history. He was a crucial bridge figure, blending the meticulous realism of the North with the light, color, and drama of Italy. He pioneered new approaches to landscape painting, particularly night scenes and atmospheric effects, demonstrating a sensitivity to the nuances of light that was unprecedented. His small, intense works on copper offered a new model for cabinet painting, proving that profound emotion and complex narratives could be conveyed on an intimate scale.

Though his career spanned little more than a decade, his innovations resonated deeply, influencing some of the greatest masters of the Baroque era in the Netherlands, Flanders, Italy, and France. He elevated landscape from mere background to an active participant in the narrative, imbued with mood and meaning. Adam Elsheimer's legacy lies in the luminous intensity of his vision, a testament to the power of quiet observation and poetic transformation that continues to captivate viewers centuries later. He remains a "painter's painter," admired for his technical brilliance and the unique emotional depth he achieved within his jewel-like creations.