Joachim Anthonisz. Wtewael (pronounced approximately "OO-te-vahl"), a pivotal figure in the art of the Dutch Golden Age, stands as one of the last and most brilliant exponents of Northern Mannerism. Born in Utrecht in 1566 and dying there in 1638, his life and career bridged a period of profound artistic and societal transformation. Wtewael's oeuvre is characterized by its dazzling color, intricate compositions, elegantly elongated figures, and a penchant for mythological and biblical narratives, often imbued with a subtle eroticism and intellectual wit. While his contemporaries increasingly embraced naturalism, Wtewael remained a steadfast champion of the sophisticated, artificial, and highly refined Mannerist aesthetic, leaving behind a legacy of exquisitely crafted paintings, primarily on copper and panel, that continue to captivate viewers with their technical brilliance and imaginative power.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Utrecht

Joachim Wtewael was born into an artisanal family in Utrecht, a city with a rich artistic heritage that would play a significant role in his development. His father, Anthonis Jansz. Wtewael, was a glass painter or glass engraver, and it was under his tutelage that Joachim likely received his initial artistic training. Working with glass would have instilled in him an appreciation for luminous color and precise draughtsmanship, qualities that would become hallmarks of his later work in oil.

Around the age of eighteen, in approximately 1584, Wtewael sought more specialized training in oil painting. He became a pupil of Joost de Beer, a Utrecht painter who had himself been a student of the renowned Flemish artist Frans Floris. While De Beer is not a widely celebrated name today, his workshop was a significant training ground in Utrecht. Through De Beer, Wtewael would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic currents, including the Italianate influences that Floris had helped popularize in the North. This period laid the foundational skills upon which Wtewael would build his distinctive style. Utrecht, at this time, was a predominantly Catholic city, which influenced the types of commissions available, though Wtewael himself was a staunch Protestant.

The Transformative Journey: Italy and France

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his era, Wtewael understood the importance of experiencing Italian art firsthand. Around 1586, he embarked on a formative journey that would last approximately four years, taking him through Italy and France. This "Grand Tour" was a crucial rite of passage, offering exposure to classical antiquity and the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and contemporary Mannerism.

During his time in Italy, he is known to have spent two years in Padua, in the service of the Bishop of St. Malo. This period would have allowed him to absorb the Venetian school's emphasis on rich color and dynamic compositions, as seen in the works of masters like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto. The sophisticated, elongated figures and complex allegories of Italian Mannerists such as Parmigianino or Giambologna (in sculpture) would also have resonated with his developing sensibilities.

His travels in France further broadened his artistic horizons. He would have encountered the elegant and often erotic art of the School of Fontainebleau, with artists like Rosso Fiorentino and Primaticcio having established a vibrant center of Mannerist art there. This exposure to diverse artistic expressions—from the High Renaissance to the various regional schools of Mannerism—profoundly shaped Wtewael's style, equipping him with a sophisticated visual vocabulary that he would later synthesize into his unique artistic voice upon his return to Utrecht.

Return to Utrecht and Rise to Prominence

Wtewael returned to his native Utrecht around 1590, a mature artist ready to establish his career. In 1592, he was admitted as a master to the Utrecht Saddlers' Guild, which at the time also encompassed painters. He was, in fact, one of the founding members when painters were formally incorporated. This marked his official entry into the professional artistic community of the city.

His style, heavily influenced by his European travels, stood out. He brought with him a sophisticated, international Mannerist aesthetic that appealed to a discerning clientele. Wtewael quickly gained recognition for his meticulously detailed paintings, often small in scale and executed on copper, a support that enhanced the jewel-like brilliance of his colors and the smoothness of his finish. These cabinet pictures were highly prized by collectors. He also undertook larger commissions on panel and canvas, demonstrating his versatility.

Beyond his artistic pursuits, Wtewael was an astute businessman. He became a successful merchant dealing in flax and linen, an enterprise that brought him considerable wealth and social standing. This financial independence likely afforded him greater artistic freedom, allowing him to pursue his preferred style and subject matter without being entirely dependent on commissions. He was also active in civic life, serving on the Utrecht town council and as a member of the Calvinist Reformed Church, indicating his respected position within the community.

The Hallmarks of Wtewael's Mannerist Style

Wtewael is considered one of the leading figures of late Northern Mannerism, an international courtly style characterized by elegance, artifice, and intellectual sophistication. His works embody many of its key features:

Elongated and Contorted Figures: Human figures in Wtewael's paintings are often slender, with elongated limbs and gracefully twisted poses (the figura serpentinata). These stylized figures, derived from Italian Mannerist models like those of Parmigianino or Spranger, prioritize elegance and decorative effect over strict anatomical naturalism.

Vibrant and Artificial Color Palettes: Wtewael employed a rich and often non-naturalistic color palette. He favored bright, jewel-like hues—pinks, acidic yellows, cool blues, and vivid greens—applied with remarkable smoothness, especially in his works on copper. These colors contribute to the fantastical and otherworldly quality of his scenes.

Complex and Crowded Compositions: His compositions are frequently dense and dynamic, filled with numerous figures, intricate details, and overlapping forms. He masterfully organized these complex arrangements, creating a sense of visual richness and narrative energy.

Emphasis on Detail and Finish: Wtewael was a meticulous craftsman. His paintings are characterized by a high degree of finish and an extraordinary attention to detail, from the rendering of fabrics and jewelry to the depiction of flora and fauna. This precision is particularly evident in his small-scale works on copper.

Erotic Undertones and Intellectual Wit: Many of Wtewael's mythological and even some biblical scenes carry subtle erotic undertones. He often depicted nude or semi-nude figures in alluring poses, appealing to the sophisticated tastes of his patrons. His works can also contain complex allegories and intellectual puzzles, inviting viewers to decipher their hidden meanings.

Thematic Repertoire: Mythology, Religion, and More

Wtewael's subject matter was diverse, though he showed a clear preference for mythological and biblical narratives that allowed for the depiction of dynamic action and the human form.

Mythological Scenes: Ovid's Metamorphoses and other classical texts provided a rich source of inspiration for Wtewael. These stories offered opportunities to depict dramatic encounters, divine interventions, and the beauty of the nude figure.

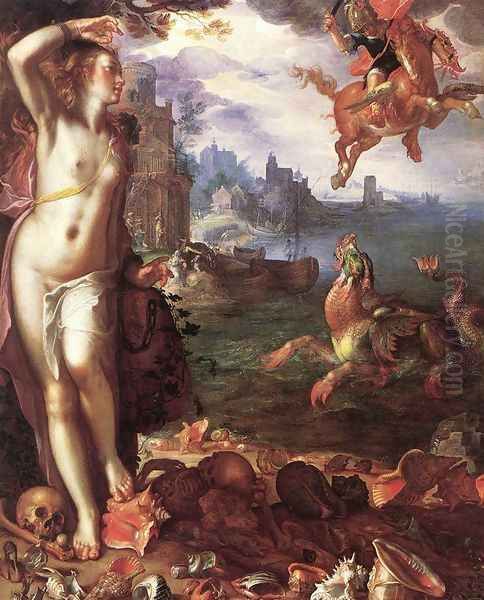

Perseus and Andromeda (1611, Louvre, Paris): This iconic work showcases Wtewael's mastery. Andromeda, chained to a rock, is rendered with pale, luminous skin, her pose a graceful S-curve. Perseus descends dramatically from the sky, while the sea monster lurks below. The painting is a symphony of vibrant colors and exquisite details, from Andromeda's jewelry to the iridescent scales of the monster.

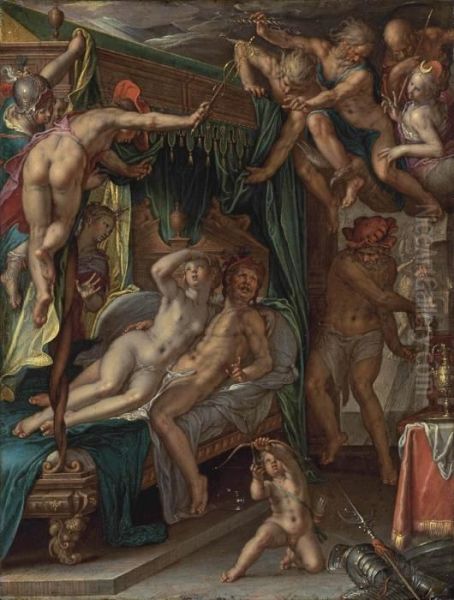

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan (c. 1604-1608, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles): A popular theme, Wtewael depicts the illicit lovers caught in Vulcan's net, surrounded by the mocking gods. The scene is filled with dynamic figures, rich colors, and a playful eroticism. He painted several versions of this subject, each demonstrating his skill in handling complex multi-figure compositions on a small copper plate.

The Judgment of Paris (1615, National Gallery, London): Another favorite mythological subject, allowing for the depiction of three beautiful goddesses – Juno, Minerva, and Venus – vying for the golden apple. Wtewael’s rendition is typically elegant, with elongated nudes and a lush landscape setting.

The Golden Age (c. 1605, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This idyllic scene, depicting humanity in a state of primordial innocence and abundance, allowed Wtewael to explore the nude figure in a harmonious natural setting, reflecting a common Mannerist theme of nostalgia for a perfect past.

Biblical Narratives: Wtewael also produced numerous paintings of religious subjects, often choosing dramatic or emotionally charged moments from the Old and New Testaments.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (various versions, e.g., c. 1607, Centraal Museum, Utrecht): These scenes are typically crowded with figures—shepherds, angels, and the Holy Family—rendered with Wtewael's characteristic vibrant colors and attention to detail. The artificial lighting and dynamic poses are hallmarks of his Mannerist approach to sacred themes.

Moses Striking the Rock (1624, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): This painting depicts the Old Testament miracle with a multitude of figures eagerly collecting the gushing water. The composition is dense and energetic, showcasing Wtewael's ability to manage large groups of figures within a coherent narrative.

The Raising of Lazarus (c. 1600, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille): A dramatic scene where Christ's divine power is evident. Wtewael captures the astonishment of the onlookers and the emerging figure of Lazarus with theatrical flair.

The Temptation of Adam and Eve (undated, various collections): A theme that allowed for the depiction of the nude human form in a pivotal biblical moment, often with a lush, detailed Edenic background.

Portraits and Other Subjects: While less common, Wtewael did paint portraits, including a notable self-portrait (1601, Centraal Museum, Utrecht) and portraits of his family. These works, while more restrained than his narrative scenes, still exhibit his keen eye for detail and character. He also painted some kitchen and market scenes, aligning with a genre popular in Netherlandish art, often imbued with moralizing undertones. His Charity (1627) is a tender allegorical depiction.

Wtewael and His Contemporaries: A Network of Influences

Wtewael operated within a vibrant artistic milieu, both in Utrecht and in the broader Netherlandish and European context. His style was shaped by, and in turn contributed to, the Mannerist currents of his time.

His teacher, Joost de Beer, provided his initial grounding. However, the influence of more prominent figures is more discernible in his mature work. The Haarlem Mannerists, particularly Hendrick Goltzius and Cornelis van Haarlem, were key figures in the development of Northern Mannerism. Goltzius, renowned for his virtuosic prints and later paintings, explored exaggerated musculature and complex poses that certainly informed Wtewael's approach to the human figure. Cornelis van Haarlem's large-scale mythological and biblical scenes, with their crowded compositions and fleshy nudes, also share affinities with Wtewael's work.

Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651) was Wtewael's direct contemporary in Utrecht and another leading Mannerist painter who later transitioned towards a more Baroque style. While their styles differed—Bloemaert's often being more robust and painterly—they were the two dominant figures in Utrecht art at the turn of the 17th century. Both artists played crucial roles in training the next generation of Utrecht painters.

The influence of international Mannerism, particularly from the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, was also significant. Artists like Bartholomeus Spranger, whose sophisticated and erotic mythological paintings were widely disseminated through prints (many engraved by Goltzius), helped to define the international Mannerist style that Wtewael embraced. Other Rudolfine artists like Hans von Aachen and Joseph Heintz the Elder further exemplified this elegant, intellectual, and often sensual aesthetic.

Wtewael's adherence to Mannerism is notable, especially as artistic tastes in Utrecht began to shift in the 1620s with the rise of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerard van Honthorst, and Dirck van Baburen, who had traveled to Rome and absorbed the dramatic realism and chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, brought a new, more naturalistic style to the city. Wtewael, however, largely remained committed to his established Mannerist idiom, continuing to produce his refined and jewel-like paintings until his death.

The Wtewael Workshop and Artistic Progeny

Like many successful artists of his time, Wtewael likely maintained a workshop, though details about its operation are scarce. His most notable artistic successor was his son, Peter Wtewael (1596-1660). Peter initially painted in a style very close to his father's, producing mythological and biblical scenes that are sometimes difficult to distinguish from Joachim's work. However, Peter's career was relatively short-lived, as he largely abandoned painting to focus on the family flax business and civic duties, following in his father's footsteps in more ways than one. Another son, Johan Wtewael (1598-1652), also seems to have been active as a painter, though his work is less well-known.

The extent of Joachim Wtewael's influence on other Utrecht painters beyond his sons is debatable, especially given the rising tide of Caravaggism and, later, Dutch Classicism. However, his distinctive style and high-quality output certainly contributed to the rich artistic tapestry of Utrecht during the Dutch Golden Age.

Later Career, Enduring Style, and Death

Wtewael continued to be productive throughout his long career. Even as younger artists in Utrecht and elsewhere in the Netherlands embraced new stylistic trends, Wtewael remained remarkably consistent in his Mannerist approach. His late works, such as Moses Striking the Rock (1624) or The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis (c. 1620s), still exhibit the vibrant colors, elongated figures, and complex compositions that characterized his earlier output. This steadfastness can be seen either as a testament to his unwavering artistic vision or perhaps as a sign of his detachment from the evolving mainstream, secure in his own success and clientele.

His involvement in the flax trade and civic affairs continued alongside his painting. He served multiple terms on the Utrecht town council and was a respected elder in the Reformed Church. This dual identity as both a successful artist and a prosperous burgher was not uncommon in the Dutch Republic, where art was increasingly integrated into the fabric of urban commercial life.

Joachim Wtewael died on August 1, 1638, in his native Utrecht, at the age of 72. He was buried in the Buurkerk, a prominent church in the city. He left behind a considerable fortune and a significant body of artwork that testified to a lifetime of dedicated craftsmanship and artistic innovation within the Mannerist tradition.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For a period after his death, as Baroque naturalism and Classicism became the dominant styles, Wtewael's Mannerist art, with its perceived artificiality, fell somewhat out of fashion. Like many Mannerist artists, his work was sometimes overlooked or undervalued in subsequent centuries that prized different aesthetic qualities.

However, the 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a significant re-evaluation and renewed appreciation for Mannerism in general, and for Wtewael's contributions in particular. Art historians and the public alike have come to recognize the unique beauty, technical brilliance, and intellectual depth of his work. His paintings are now prized possessions in major museums around the world, including the Louvre (Paris), the National Gallery (London), the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), and the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles).

A landmark monographic exhibition, "Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638)," organized by the Centraal Museum, Utrecht, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2015-2016, brought his work to a wider international audience and solidified his reputation as a major master of the Dutch Golden Age. This exhibition highlighted the full range of his talents, from his dazzling mythological scenes on copper to his more intimate religious paintings and portraits.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Joachim Wtewael was an artist of exceptional skill and a distinctive vision. He navigated the transition from the 16th to the 17th century, a period of immense change in European art, by remaining largely faithful to the sophisticated and elegant ideals of Northern Mannerism. His ability to combine meticulous detail with dynamic compositions, vibrant, almost surreal colors with graceful, elongated figures, and sensual allure with intellectual content, marks him as a unique and fascinating figure.

His works transport viewers to a world of myth and miracle, rendered with a jeweler's precision and a storyteller's flair. As one of the last great Mannerists, Wtewael created a body of work that is both a culmination of that international style and a testament to his individual genius. In the diverse landscape of the Dutch Golden Age, Joachim Wtewael shines as a master of luminous color, intricate design, and enduring artistic appeal, a painter whose delightful and sophisticated creations continue to enchant and intrigue.