Leonaert Bramer (1596-1674) stands as a distinctive and somewhat enigmatic figure within the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age. Born and primarily active in Delft, a city renowned for its artistic output, Bramer carved a unique niche for himself through his mastery of nocturnal scenes, his prolific work as a draftsman and illustrator, and his intriguing connections to his more famous townsman, Johannes Vermeer. Though perhaps less universally recognized today than contemporaries like Rembrandt or Vermeer, Bramer was a highly respected and innovative artist in his own time, whose work bridges Italianate influences with Dutch sensibilities.

His reputation was significantly built upon his evocative paintings of night scenes, often illuminated by dramatic, artificial light sources. This earned him the appreciative, if informal, title "Leonaert of the Night." Beyond these captivating canvases, Bramer demonstrated remarkable versatility, tackling historical, biblical, mythological, and genre subjects with equal facility. Furthermore, his extensive body of drawings and illustrations reveals a narrative talent that some scholars see as a precursor to modern graphic storytelling. This exploration delves into the life, work, and legacy of this multifaceted Delft master.

Early Life and Formative Travels in Italy

Leonaert Bramer was born in Delft in 1596. Details about his earliest training remain scarce, a common situation for many artists of this period. However, it is clear that the most decisive formative experience of his early career was his extended journey to Italy, undertaken likely around 1614 and lasting until approximately 1628. This period abroad was crucial for absorbing the artistic currents sweeping through Italy, particularly the dramatic intensity of the Baroque.

During his time in Italy, Bramer traveled extensively, visiting key artistic centers such as Rome, Venice, Florence, Mantua, and Padua. In Rome, he would have encountered the powerful legacy of Caravaggio, whose revolutionary use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – was transforming painting across Europe. While not a direct follower in the strictest sense, the impact of Caravaggism is evident in Bramer's later penchant for dramatic lighting and tenebrism.

Perhaps the most significant individual influence Bramer encountered was the German painter Adam Elsheimer, who was active in Rome until his death in 1610 but whose influence persisted. Elsheimer specialized in small-scale paintings on copper, often depicting biblical or mythological scenes set within meticulously rendered landscapes or nocturnal settings, illuminated by moonlight or flickering torches. Bramer's own preference for smaller formats, intricate details, and atmospheric night scenes owes a considerable debt to Elsheimer's example. Bramer's interaction with other Northern artists working in Italy, often grouped under the name "Bentvueghels," also likely played a role in his development.

Return to Delft and Mature Style

Around 1628, Leonaert Bramer returned to his native Delft, bringing with him a wealth of experience and a style significantly shaped by his Italian sojourn. He quickly established himself within the city's artistic community, joining the Guild of Saint Luke in 1629. Delft, at this time, was a thriving center for the arts and sciences, fostering an environment where innovation was valued. Bramer's unique blend of Italianate drama and Northern European detail found a receptive audience.

His mature style is characterized by a dynamic energy, often featuring numerous small, animated figures within complex architectural or landscape settings. His brushwork could be fluid and expressive, contributing to the overall liveliness of his compositions. Central to his approach was the sophisticated manipulation of light and shadow. He frequently employed strong contrasts, using focused light sources – candles, torches, divine radiance, or moonlight – to highlight key figures and create a sense of mystery or drama, particularly in his famed nocturnal scenes.

Bramer worked across various genres. History painting, encompassing biblical narratives, mythological tales, and historical events, formed a significant part of his output. He also produced genre scenes, depicting everyday life, albeit often with a theatrical flair. His palette could range from rich, dark tones, typical of his night scenes, to brighter, more varied colors when the subject demanded. He often painted on panel or copper, favoring relatively small formats, although he also undertook larger commissions, including ambitious but ultimately ill-fated fresco projects.

Master of Nocturnes: "Leonaert of the Night"

Bramer's most enduring fame rests on his exceptional skill in depicting nocturnal scenes. His contemporaries recognized this talent, bestowing upon him the nickname "Leonaert van de Nacht" (Leonaert of the Night). These works are not merely dark paintings; they are carefully orchestrated studies in illumination and atmosphere. Bramer explored the effects of various light sources – the cold glow of the moon, the warm flicker of candles or torches, the supernatural radiance accompanying divine figures.

In paintings like the Magical Scene (Bordeaux), Bramer creates an atmosphere thick with mystery and intrigue. Figures emerge from deep shadows, their forms sculpted by raking light. The interplay between illuminated areas and profound darkness generates suspense and focuses the viewer's attention. His ability to render different qualities of light and their effect on surfaces and figures was remarkable, lending these scenes a captivating, almost theatrical quality.

Another example, Three Sleeping Men, showcases his imaginative approach to night settings. The composition relies heavily on the dramatic potential of chiaroscuro to create mood and narrative suggestion. Similarly, Saint John with the Magician Hermogenes uses directed light not only to illuminate the figures but also to underscore the spiritual conflict depicted. Bramer's night scenes often possess a nervous energy, conveyed through flickering light effects and the animated gestures of his small figures, distinguishing his work from the calmer, more contemplative candlelit scenes of artists like Georges de La Tour in France.

Diverse Subjects and Representative Works

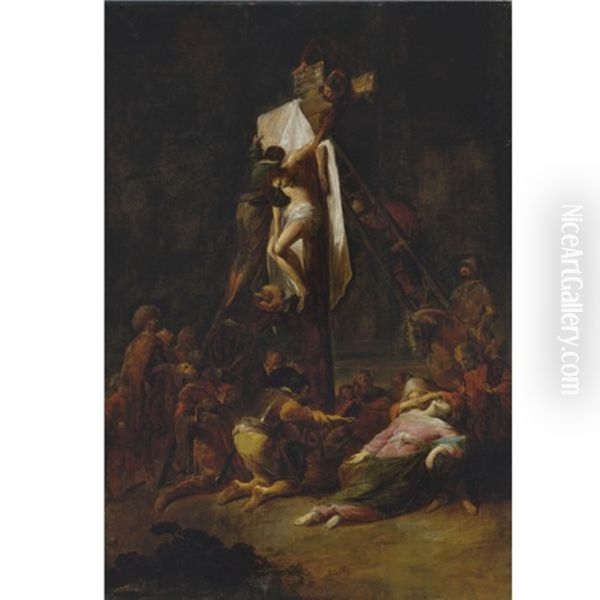

While celebrated for his nocturnes, Leonaert Bramer's oeuvre demonstrates considerable thematic diversity. He was deeply engaged with biblical narratives, drawing subjects from both the Old and New Testaments. His Judgment of the Betrayal of Judas, part of a larger (though now dispersed) series on the Life of Christ, exemplifies his ability to convey complex emotional and theological moments. The work showcases his characteristic use of multiple figures, dynamic composition, and expressive lighting to heighten the drama of the scene.

Mythological and allegorical subjects also feature in his work, reflecting the classical education and interests common among artists and patrons of the era. His history paintings often drew upon ancient history and literature. Furthermore, Bramer produced genre scenes, sometimes depicting musicians, soldiers, or scholars, often infused with the same dramatic lighting found in his more elevated subjects.

Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist is another powerful example of his work, combining a popular biblical subject with intense psychological drama and stark chiaroscuro. The confined interior space, illuminated by an unseen light source, focuses attention on the grisly trophy and Salome's reaction. The Adoration of the Magi, a subject he painted multiple times, allowed him to explore the effects of divine light contrasting with the darkness of the night, often filling the scene with a multitude of figures and exotic details associated with the Magi's entourage. These works reveal an artist comfortable with complex narratives and skilled in translating them into compelling visual terms.

The Prolific Illustrator and Draftsman

Beyond his paintings, Leonaert Bramer was an exceptionally prolific draftsman and illustrator. It is estimated that he produced well over 1,300 drawings, a testament to his tireless energy and fertile imagination. These drawings were not merely preparatory studies for paintings but often finished works in their own right, executed in various techniques including pen and ink, wash, and chalk. Many were created in series, illustrating specific texts or themes.

He created extensive illustrative cycles for the Bible, Ovid's Metamorphoses, and the popular Spanish picaresque novel Lazarillo de Tormes. His illustrations for Till Eulenspiegel also survive. These series demonstrate a remarkable narrative capacity. Bramer visualized sequential moments from these stories, arranging figures and settings to convey the unfolding action effectively. The sheer number of drawings and the serial nature of many projects have led some modern scholars to view Bramer's illustrative work as an important, if unintentional, precursor to the graphic novel or comic strip.

His drawing style is often characterized by rapid, energetic lines and expressive use of wash to create tonal contrasts and model form. The figures, though small, are typically animated and full of character. These drawings provide invaluable insight into his creative process and his deep engagement with literary and religious sources. They also likely served a distinct market, appealing to collectors who appreciated drawings as an independent art form, a growing trend during the Dutch Golden Age. His graphic output rivals that of many contemporaries known primarily for drawing, like Rembrandt himself in terms of narrative scope in series.

Bramer and Vermeer: A Delft Connection

One of the most discussed aspects of Leonaert Bramer's life is his relationship with his younger Delft contemporary, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Living and working in the same relatively small city, and both members of the Guild of Saint Luke, they undoubtedly knew each other. The precise nature of their artistic relationship, however, remains a subject of scholarly debate. Some early accounts, including that of Arnold Houbraken in his Groote Schouburgh (1718-21), suggested Bramer might have been Vermeer's teacher.

Modern art historians are generally skeptical of a formal teacher-pupil relationship. Vermeer's mature style, with its serene monumentality, cool light, and focus on contemporary interior scenes, differs significantly from Bramer's energetic, often crowded, and dramatically lit compositions. However, Bramer's documented interactions with the Vermeer family are undeniable and significant.

Most notably, in April 1653, when Vermeer sought to marry the Catholic Catharina Bolnes, her mother, Maria Thins, initially objected strongly. Leonaert Bramer, himself a lifelong Catholic, intervened on Vermeer's behalf. Along with a Captain Melling, Bramer visited Maria Thins and argued in favor of the marriage, persuading her to at least allow it to proceed, even if she did not give a formal written consent initially. Bramer's signature appears on the document recording this intervention. This act suggests a close and supportive relationship, positioning Bramer as a respected figure willing to advocate for the younger artist. While direct stylistic influence may be limited, their personal connection within the Delft art scene is historically certain.

Bramer in the Context of the Dutch Art World

Leonaert Bramer operated within the vibrant ecosystem of the Dutch Golden Age, interacting with and responding to various artistic trends and figures. While based in Delft, his Italian experiences gave his work an international dimension less common among purely Dutch-trained artists. His style, blending Baroque drama with local tastes, set him apart.

His relationship with Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) appears to have been indirect. While both artists shared a profound interest in chiaroscuro and biblical subjects, their approaches differed considerably. Rembrandt's psychological depth and textured brushwork contrast with Bramer's more animated, narrative focus. However, Bramer's work, particularly pieces like The Adoration of the Magi, has occasionally been cited as a possible influence on Rembrandt's early treatments of similar subjects, perhaps via prints or shared knowledge within artistic circles. Bramer certainly knew artists closer to Rembrandt, like Rembrandt's former teacher Pieter Lastman, whose history painting influenced many.

Within Delft itself, Bramer was a senior figure by the time artists like Carel Fabritius (1622-1654), a documented pupil of Rembrandt, arrived in the city around 1650. Fabritius's own experiments with light, perspective, and illusionism represent a different direction from Bramer's work, though both contributed to Delft's reputation for artistic innovation before Fabritius's tragic death in the gunpowder explosion of 1654. Bramer would also have known other Delft painters like the genre specialists Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684) and Nicolaes Maes (1634-1693, a Rembrandt pupil who worked in Delft for a period), and the architectural painters Gerard Houckgeest and Emanuel de Witte.

Bramer's connections extended beyond Delft. He associated with artists like Jan Lievens (1607-1674), who worked closely with Rembrandt in their early Leiden years, and Govert Flinck (1615-1660), another prominent Rembrandt pupil. The Dutch art world was interconnected through guilds, travel, and the art market, facilitated by dealers like Hendrick Uylenburgh, who handled work by Rembrandt and his circle. Bramer's unique style, however, ensured he maintained a distinct artistic identity amidst these contemporaries like Gerard ter Borch or Jan Steen.

Patronage and Ambitious Commissions

Leonaert Bramer enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime, attracting patronage from various quarters. His smaller paintings and numerous drawings likely found buyers among the growing Dutch middle class and specialized collectors who appreciated his distinctive style and narrative skill. His reputation extended beyond Delft, evidenced by commissions from prominent figures.

Among his most important patrons was Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange, the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. Around the late 1630s or 1640s, Bramer received commissions to contribute to the decoration of the Prince's hunting lodge, Honselaarsdijk Palace, near The Hague. This prestigious project involved several leading artists of the day. Bramer was tasked with painting frescoes, a medium deeply associated with his Italian training but rarely practiced successfully in the damp Dutch climate.

He also received commissions for decorations from Frederik Hendrik's wife, Amalia van Solms, for her apartments within Honselaarsdijk, contributing to a cycle based on the popular pastoral romance Il Pastor Fido. Other documented commissions include work for the Prinsenhof in Delft, the former monastery famous as the site of William the Silent's assassination. These large-scale projects demonstrate the high regard in which Bramer was held, entrusted with significant decorative schemes alongside artists like Jacob Jordaens and Gerrit van Honthorst (though their contributions were often easel paintings rather than true frescoes).

Frescoes: A Bold but Fleeting Endeavor

Bramer's engagement with fresco painting marks him as an outlier in 17th-century Dutch art. True fresco (buon fresco), involving painting on wet plaster, was the dominant medium for large-scale wall decoration in Italy but presented significant technical challenges in the colder, damper climate of the Netherlands. Most Dutch wall decorations were executed on canvas and then mounted, or used techniques less durable than true fresco.

His training in Italy undoubtedly exposed him to the grandeur and techniques of Italian fresco cycles. Upon his return, Bramer ambitiously sought to apply this knowledge in his homeland. His commissions for Honselaarsdijk and the Prinsenhof provided opportunities to work on a monumental scale. However, contemporary accounts and the lack of surviving examples suggest these frescoes deteriorated relatively quickly due to the adverse climate.

Despite their lack of longevity, Bramer's fresco attempts are significant. They highlight his ambition, his connection to Italian traditions, and his willingness to experiment with challenging techniques. They represent a rare instance of an attempt to directly import a major Italian artistic practice into the Dutch Republic. The failure of these works likely reinforced the Dutch preference for easel painting and large-scale canvases for decorative schemes, even within palatial settings.

Later Life, Reputation, and Legacy

Leonaert Bramer remained active in Delft throughout his long career. He was a respected member of the community and held positions of authority within the Guild of Saint Luke on multiple occasions, serving as its headman or dean several times between 1654 and 1671. This indicates the esteem in which he was held by his fellow artists. Unlike many Dutch artists who specialized narrowly, Bramer maintained a broad practice encompassing painting in various genres and prolific drawing.

He never married and is documented as being a devout Roman Catholic, a status that connected him to patrons and fellow artists like the Vermeer family, who were also Catholic (Vermeer converted upon marriage). His personal life appears relatively uneventful compared to the dramatic lives of some contemporaries. He continued to paint and draw into his later years, dying in Delft in 1674 at the age of 78.

During his lifetime, Bramer enjoyed a solid reputation, particularly for his distinctive night scenes and his skill as a draftsman. Arnold Houbraken, writing a few decades after Bramer's death, acknowledged his fame, especially for his handling of light. However, subsequent shifts in taste, perhaps favoring the perceived realism of other Dutch masters, may have led to a relative decline in his prominence compared to figures like Rembrandt, Vermeer, or Frans Hals. Many of his works were likely lost over time, particularly the fragile frescoes.

Enduring Influence and Conclusion

Despite periods of relative obscurity, Leonaert Bramer's contribution to the Dutch Golden Age is undeniable and significant. His primary influence lies in his innovative and atmospheric treatment of nocturnal scenes. He demonstrated how artificial light and deep shadow could be used to create drama, mood, and narrative focus, influencing painters who explored similar themes. His mastery of chiaroscuro, learned in Italy but adapted to a Dutch context, remains a hallmark of his style.

His vast output of drawings and illustrations represents another major aspect of his legacy. The narrative power and sequential nature of his illustrative series offer a fascinating glimpse into visual storytelling in the 17th century and secure his place as one of the era's most important draftsmen. His connection to Vermeer, particularly his role in facilitating Vermeer's marriage, adds a layer of historical intrigue, linking him personally to one of art history's most revered figures.

Today, Leonaert Bramer's paintings and drawings are held in major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Louvre in Paris, the Prado in Madrid, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and many others. Exhibitions and ongoing scholarship continue to shed light on his unique position within 17th-century Dutch art. He emerges not just as "Leonaert of the Night," but as a versatile, imaginative, and technically skilled artist who successfully navigated the rich artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate with its energy and distinctive vision. He remains a crucial figure for understanding the diversity and international connections of art in Delft and the broader Dutch Republic.