Introduction: A Defining Force in Satire

James Gillray stands as a towering figure in the history of British art and social commentary. Active during the tumultuous late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period marked by revolution abroad and political upheaval at home, Gillray wielded his etching needle like a surgeon's scalpel, dissecting the follies, vices, and anxieties of his age with unparalleled wit and ferocity. Born in Chelsea, London, likely in 1756 (though some sources cite 1757), and dying in 1815, Gillray rose from relative obscurity to become the most influential and arguably the greatest caricaturist of his era. Often hailed as the "Father of Political Cartooning," his work transcended mere illustration, becoming a powerful force in shaping public opinion and providing a vivid, often grotesque, chronicle of Georgian England. His prolific output, primarily concentrated between 1792 and 1810, established a benchmark for graphic satire that continues to resonate with artists and audiences today. This exploration delves into the life, work, techniques, and enduring legacy of James Gillray, examining the unique blend of artistic skill, savage humour, and acute political insight that defined his remarkable career.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

James Gillray's origins were relatively humble. Born in Chelsea, then a village on the outskirts of London, on August 13, 1756, he was the son of James Gillray Sr., a Scottish Highlander who had fought for the Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Culloden (1746) and later lost an arm at the Battle of Fontenoy (1745). His father subsequently became an out-pensioner at the Royal Hospital Chelsea. This background, marked by military service and physical sacrifice, may have subtly informed Gillray's later depictions of soldiers, war, and the human cost of conflict, sometimes imbued with a pathos that contrasts with his usual biting satire. One poignant example, though less famous than his political works, depicts a legless veteran begging fruitlessly, perhaps echoing his father's experiences or the plight of many soldiers returning from Britain's numerous wars.

Gillray received some basic education, possibly including training in letter-engraving, a common starting point for aspiring printmakers. His formal artistic training was somewhat sporadic. He spent time associated with the Moravian Brotherhood, a strict religious sect his parents belonged to, but reportedly found the constraints stifling and ran away to join a troupe of travelling players. However, he soon returned to London and pursued engraving more seriously. He is known to have been admitted as a student to the Royal Academy Schools in 1778, although his attendance seems to have been brief and perhaps unsuccessful in terms of conforming to the academic ideals promoted by figures like its president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Despite this, his time there would have exposed him to the canons of high art, knowledge he would later brilliantly subvert and parody in his satirical prints. His early professional work included reproductive engravings after other artists, a common practice that honed his technical skills but offered little scope for his burgeoning originality.

The Rise of a Satirical Genius and the Humphrey Partnership

By the late 1770s and early 1780s, Gillray began producing original satirical prints, initially published anonymously or under pseudonyms. His distinctive style, characterized by vigorous lines, expressive distortion, and a keen eye for contemporary events and personalities, quickly gained attention. A pivotal moment in his career was the beginning of his long association with the publisher and printseller Hannah Humphrey. From the early 1790s until his death, Gillray lived and worked above her successive print shops in fashionable areas of London, most famously at 27 St James's Street.

This arrangement was crucial for Gillray's success. Humphrey provided him with financial stability, artistic freedom, and a prominent outlet for his work. Her shop window became a focal point of London life, where crowds gathered daily to view Gillray's latest, often scandalous, commentaries on the political and social scene. This direct and immediate form of publication allowed Gillray's prints to function almost like a visual newspaper, responding rapidly to events and influencing public discourse in real-time. The nature of their personal relationship remains a subject of speculation – they never married, but their close, lifelong association suggests a deep personal and professional bond. Humphrey managed the business side, allowing Gillray to focus on his art, and her shop became synonymous with his biting satire. She continued to publish his work and manage his affairs even during his later periods of illness and decline, and he ultimately died in her care.

Artistic Style: Exaggeration, Energy, and Parody

Gillray's artistic style is immediately recognizable for its dynamism, its often brutal exaggeration, and its sophisticated use of visual language. He was a master of the etching technique, using fluid, energetic lines to capture movement and expression. Unlike the more decorative, sometimes gentler satire of his contemporary Thomas Rowlandson, Gillray's work often possessed a visceral, almost savage quality. He excelled at caricature, seizing upon the defining physical features and mannerisms of his subjects – King George III's bulging eyes and folksy manner, William Pitt the Younger's thinness and aloofness, Charles James Fox's bulk and dishevelment, Napoleon Bonaparte's diminutive stature and oversized ambition – and amplifying them to grotesque, yet instantly identifiable, effect.

His compositions were often complex and densely packed with detail, rewarding close examination. He frequently employed allegory and symbolism, drawing on classical mythology, biblical narratives, literary sources (especially Shakespeare and Milton), and contemporary cultural phenomena. A key element of his genius was his ability to parody the conventions of 'high art'. He would often structure his satires based on well-known paintings by Old Masters or contemporary academicians like Sir Joshua Reynolds or the American-born historical painter Benjamin West, using the contrast between the grand style and the often vulgar subject matter to heighten the satirical effect. This engagement with art history added layers of meaning for his educated audience and demonstrated his own artistic knowledge, elevating caricature beyond simple lampooning. The influence of earlier British satirist William Hogarth, particularly his 'modern moral subjects' presented in series like A Rake's Progress, is evident in Gillray's narrative sequences, such as the series chronicling the life of the Prince of Wales. However, Gillray's focus was more overtly political and his style generally more aggressive and less overtly moralizing than Hogarth's. The dark, fantastical elements in some works also show an affinity with the 'Gothic' sensibility explored by artists like Henry Fuseli.

Technical Mastery: Etching and Colour

Gillray's primary medium was etching, often combined with engraving for finer details or bolder lines. He possessed exceptional skill in handling the etching needle, achieving a remarkable range of tones and textures. His ability to convey character and emotion through line alone was extraordinary. While the initial prints were sold uncoloured, many were subsequently hand-coloured, usually by teams working for the publisher. This colouring, often vibrant and bold, added significantly to the prints' visual impact and commercial appeal. Although Gillray himself likely did not colour the prints sold in bulk, the colour schemes were often guided by his original intentions or established conventions, becoming an integral part of how his work was received.

He also occasionally employed other techniques like stipple engraving, particularly earlier in his career for more sentimental or decorative subjects, and sometimes aquatint was used to create tonal areas, though etching remained his dominant mode of expression. The prints were typically accompanied by titles and often speech bubbles or captions, meticulously lettered, which formed an essential part of the satire, clarifying the subject, adding puns, or putting ironic words into the mouths of the characters depicted. This integration of image and text was crucial to the effectiveness of his commentary.

Chronicling British Politics: Pitt, Fox, and King George III

The turbulent political landscape of late Georgian Britain provided Gillray with inexhaustible material. The long-running rivalry between the austere, pragmatic Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and the charismatic, liberal leader of the opposition, Charles James Fox, was a recurring theme. Gillray depicted Pitt as excessively thin, often aloof or arrogant, sometimes as a fungus growing on the crown ('An Excrescence'). Fox, in contrast, was usually portrayed as corpulent, slovenly, and associated with gambling, drinking, and radicalism. Gillray's political allegiance seemed flexible; while sometimes appearing to favour Pitt's stability, particularly during the threat of French invasion, he ruthlessly satirized both sides, exposing the opportunism and factionalism of parliamentary politics.

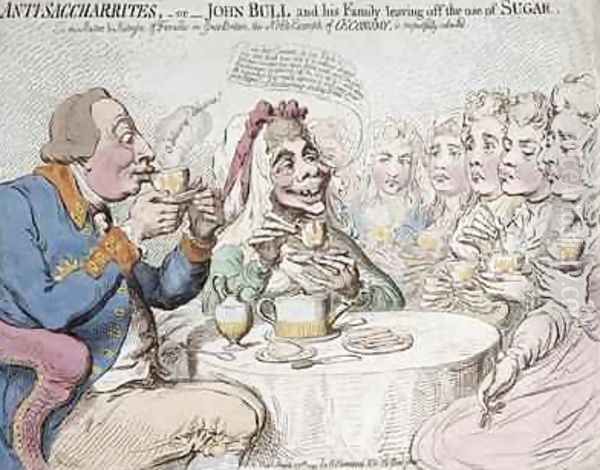

King George III and the royal family were frequent targets. The King was often depicted as 'Farmer George,' a somewhat bucolic, simple-minded figure, obsessed with economy to the point of absurdity. Queen Charlotte was often portrayed as miserly and unattractive. Their numerous children, particularly the extravagant and debt-ridden Prince of Wales (later Prince Regent and George IV), were mercilessly lampooned. A famous example is A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion (1792), showing the grossly overweight Prince slumped after a meal, surrounded by unpaid bills, picking his teeth with a fork – a powerful indictment of royal excess at a time of national hardship. Another notable print, The Anti-Saccharites, or John Bull and his Family leaving off the use of Sugar (1792), shows the King and Queen teaching their daughters to drink tea without sugar (to support the boycott of slave-produced sugar), but their expressions reveal their distaste, satirizing the perceived hypocrisy and meanness of the royal couple.

The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Threat

The French Revolution (1789 onwards) and the subsequent rise of Napoleon Bonaparte profoundly impacted Gillray's work and British society. Initially, some in Britain viewed the Revolution with cautious optimism, but as it descended into the Reign of Terror, sentiment shifted dramatically. Gillray captured this changing mood, moving from early satires on the absurdity of French fashions and ideas to horrific depictions of revolutionary violence. Prints like Un petit Souper, a la Parisienne;–or–A Family of Sans-Culotts refreshing themselves after the Fatigues of the Day (1792) graphically portrayed the revolutionaries as bloodthirsty cannibals, feeding public fears in Britain. The Zenith of French Glory;–The Pinnacle of Liberty (1793) shows a chaotic, violent scene in Paris with a fiddling sans-culotte atop a lamppost from which clergymen hang, a brutal commentary on the destruction of the old order.

Napoleon Bonaparte became one of Gillray's most persistent and iconic targets. He almost single-handedly created the enduring caricature of Napoleon as 'Little Boney,' an absurdly small, petulant, yet menacing figure, often shown wearing an oversized bicorne hat and boots. Gillray depicted Napoleon's insatiable ambition and his threat to Britain in numerous famous prints. The Plumb-pudding in danger,—or—State Epicures taking un Petit Souper (1805) shows Pitt and Napoleon carving up the world (represented as a plum pudding) between them, a brilliant visual metaphor for geopolitical rivalry. Uncorking Old Sherry (1805) depicts Pitt as Prime Minister unleashing the fiery politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan (like potent sherry) against a diminutive Napoleon. Britannia between Scylla and Charybdis (1793) shows Pitt steering the ship of state between the rock of democracy (symbolized by the fires of revolution) and the whirlpool of arbitrary power (symbolized by an inverted crown). Gillray's anti-Napoleonic prints were immensely popular and played a significant role in bolstering British morale and demonizing the enemy during the long wars. His imagery was so powerful that it influenced how Napoleon was perceived across Europe, even being recognized by Napoleon himself, who reportedly resented Gillray's portrayals.

Social Satire: Fashion, Folly, and Everyday Life

While political commentary dominated his output, Gillray also turned his sharp eye to the social customs, fashions, and follies of the day. He satirized the extremes of fashion, such as the high waistlines and flimsy fabrics of women's dresses in prints like Fashionable Contrasts;–or–The Duchess's little Shoe yeilding to the Magnitude of the Duke's Foot (1792), which humorously contrasted the dainty shoe of the Duchess of York with the large, gouty foot of her husband. He mocked social climbers, quack doctors, artistic pretensions, and the perceived decline in public morals.

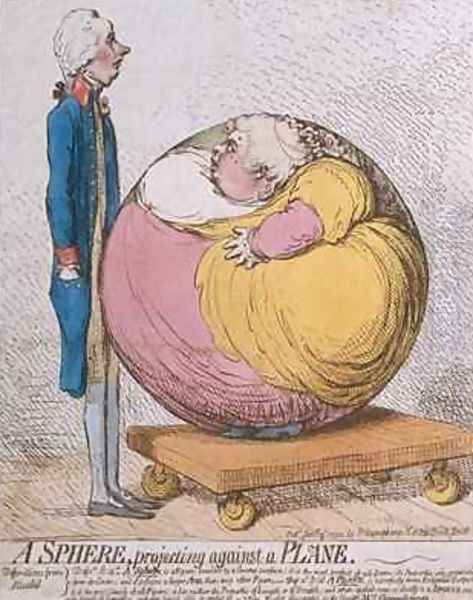

These social satires provide invaluable insights into the everyday life, anxieties, and amusements of Georgian society. They reveal a world grappling with rapid change, new wealth, and shifting social structures. Prints dealing with themes like gambling, drinking, the theatre, and public spectacles capture the vibrant, often chaotic, energy of London life. Works like A Sphere, projecting against a Plane (1792), while potentially having political undertones related to Pitt and Thurlow, also functions on a level of pure visual absurdity and commentary on perception. His depictions of crowds, whether at political rallies, theatrical performances, or simply observing events from Hannah Humphrey's shop window, are masterclasses in capturing diverse human types and reactions.

Later Years: Decline and Death

From around 1807, Gillray's health began to fail. His eyesight deteriorated, a catastrophic blow for a visual artist reliant on fine detail. He also suffered from bouts of debilitating mental illness, possibly exacerbated by years of intense work and, according to some accounts, heavy drinking. His output became more sporadic, and the quality, while occasionally still brilliant, became inconsistent. He reportedly expressed despair over his declining powers and sometimes refused to sign his later works.

In July 1811 (some sources say 1810), in a fit of delirium, he attempted suicide by throwing himself from an attic window above Hannah Humphrey's shop. He survived but was subsequently declared insane and largely ceased working. He spent his final years in the care of Miss Humphrey, experiencing periods of lucidity but ultimately succumbing to his afflictions. James Gillray died on June 1, 1815, ironically the same month as the Battle of Waterloo, the final defeat of his great nemesis, Napoleon. He was buried in the churchyard of St James's Church, Piccadilly, close to the site of Humphrey's shop where he had produced his life's work. Hannah Humphrey, his steadfast supporter, was also later buried there.

Enduring Influence and Historical Legacy

James Gillray's impact on the art of caricature and political cartooning was immense and immediate. He elevated graphic satire from a relatively minor genre to a powerful form of public discourse. His technical brilliance, imaginative scope, and fearless commentary set a standard that few have equalled. His contemporaries, including Thomas Rowlandson and Isaac Cruikshank, operated in the same vibrant print market, but Gillray's political insight and artistic ferocity were unique. His influence extended directly to the next generation, notably Isaac's son, George Cruikshank, who became a leading caricaturist in the Regency and early Victorian periods.

Across the Channel, his work was known and admired, potentially influencing French satirists like Honoré Daumier, although Daumier developed his own distinct style using lithography. In Britain, the tradition of sharp political cartooning continued through figures like John Tenniel of Punch magazine in the later 19th century, and into the 20th and 21st centuries with artists such as David Low and Martin Rowson, who explicitly acknowledge Gillray's foundational role. The Spanish master Francisco Goya, a contemporary, explored similarly dark themes of human folly and the horrors of war in his print series like Los Caprichos and The Disasters of War, sharing Gillray's unflinching gaze, though working in a different national context and artistic tradition.

Beyond his artistic influence, Gillray's work serves as an invaluable historical record. His prints offer a visceral, immediate perspective on the politics, personalities, and social anxieties of Georgian Britain, often capturing the mood and underlying tensions of the era more effectively than written accounts. Major collections of his work are held in institutions like the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University, where they continue to be studied by historians and art historians alike. While some critics then and now have found his work coarse, vulgar, or overly partisan, his genius lay in his ability to synthesize complex events into potent, memorable images, forever shaping our visual understanding of a pivotal historical period. He remains, without doubt, one of the most significant figures in the history of graphic art and a defining commentator on the human condition in all its absurdity and complexity, standing alongside major British artistic figures of his time, from the portraitist Reynolds to the landscape painters J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, as a unique and powerful voice.

Conclusion: The Unflinching Gaze

James Gillray's career was a unique confluence of artistic talent, historical circumstance, and personal audacity. Living and working through a period of intense global change, he used his art not merely to entertain but to engage, critique, and provoke. His etchings, displayed prominently in Hannah Humphrey's London shop window, became a vital part of the nation's conversation, shaping perceptions of its leaders, its enemies, and itself. With a style that blended grotesque exaggeration with sophisticated artistic parody, and a viewpoint that spared neither the powerful nor the pretentious, Gillray established political caricature as a serious art form and a potent weapon. Though his later years were marked by tragedy and decline, the vast body of work he produced remains a testament to his ferocious energy and singular vision. As the "Father of the Political Cartoon," his legacy endures not only in the works of subsequent satirists but also in the enduring power of visual commentary to dissect and influence the world around us. James Gillray's unflinching gaze captured the essence of his age, leaving behind a visual chronicle as vital and disturbing today as it was two centuries ago.