William Heath (1795-1840) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant history of British graphic satire. Active during a period of immense social and political change, Heath carved out a niche for himself with his energetic, often biting, caricatures and illustrations. Bridging the gap between the ferocious political commentary of the late Georgian era and the burgeoning illustrated journalism of the early Victorian age, Heath's work offers a fascinating window into the preoccupations, fashions, and conflicts of his time. Though his fame was perhaps eclipsed later by others, his prolific output and pioneering efforts, particularly in periodical satire, secure his place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Born likely in Northumberland around 1795, William Heath's early artistic career was markedly different from the satirical path he would later pursue. His initial focus lay in military subjects, a popular genre in the wake of the long Napoleonic Wars that had dominated British life for decades. The drama, heroism, and pageantry of warfare provided ample material for artists, and Heath contributed to this field with depictions of battles and military life.

His works from this period often took the form of aquatints, a printmaking technique capable of rendering tonal effects similar to watercolour washes, which were then frequently hand-coloured. These prints captured scenes from contemporary conflicts, including illustrations related to the Battle of Waterloo (1815) and other engagements of the Napoleonic era. An example of his work in this vein is the series The Life of a Soldier, published around 1823, which comprised eighteen hand-coloured plates illustrating various aspects of military experience, from recruitment and drill to camp life and combat. This early focus demonstrates Heath's technical skill in draughtsmanship and printmaking, laying the groundwork for his later, more famous satirical output.

The Shift to Satire

Around 1820, a noticeable shift occurred in William Heath's artistic direction. He began to move away from purely military themes and embraced the burgeoning field of social and political caricature. This transition coincided with a changing public appetite; while the Napoleonic Wars had provided endless subject matter, the post-war era brought domestic issues – political reform, economic hardship, royal scandals, and the minutiae of social etiquette – to the forefront of public consciousness.

The market for satirical prints, established by giants like James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson in the preceding decades, was robust. Heath entered this arena, bringing his established skills but developing a distinctive, energetic style. His caricatures began appearing frequently, published as individual sheets sold in the print shops that lined the streets of London, offering topical commentary that was immediate, accessible, and often humorous. This move proved successful, and Heath quickly became one of the most prolific caricaturists of the 1820s.

The "Paul Pry" Persona

A significant aspect of Heath's career in the late 1820s was his adoption of the pseudonym "Paul Pry." This name was borrowed from the title character of a highly popular comedy play by John Poole, first staged in 1825. The character Paul Pry was an incorrigibly inquisitive and meddling busybody, constantly interfering in others' affairs with the catchphrase, "I hope I don't intrude?"

By signing his prints "Paul Pry," often represented visually by a small sketch of the character peeking from behind a curtain or object, Heath tapped into this popular cultural reference. It cleverly positioned him as an observant, perhaps slightly intrusive, commentator on the follies and secrets of society and politics. This pseudonym appeared on a vast number of his prints between roughly 1827 and 1829, becoming almost a brand identity during that period. It highlighted the observational nature of his satire, suggesting he was revealing hidden truths or simply noticing the absurdities that others might miss.

Pioneering Periodical Satire: The Northern Looking-Glass

One of William Heath's most notable contributions to the history of graphic satire was his involvement with The Glasgow Looking-Glass, later renamed The Northern Looking-Glass. Launched in Glasgow in June 1825 and running until June 1826, this publication is widely considered one of the world's first magazines dedicated predominantly to satirical illustrations and comics – a precursor to later, more famous publications like Punch.

Heath was the principal artist and driving force behind the Looking-Glass. Published fortnightly, it featured lithographed sheets (a relatively new printmaking technique at the time) filled with multiple vignettes commenting on both local Glaswegian affairs and national political and social events. The format allowed for sequential narratives and juxtapositions of images, pushing the boundaries of visual storytelling. Heath's work for the Looking-Glass showcased his versatility, covering everything from political debates and civic improvements to fashion trends and social gatherings. Its innovative approach, combining topical cartoons with recurring features, laid important groundwork for the development of the comic magazine format.

Key Works and Dominant Themes

Throughout his career, William Heath produced a vast number of prints, making it challenging to single out just a few. However, certain works and recurring themes stand out. His political satires often targeted prominent figures like the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel, especially during the turbulent periods surrounding Catholic Emancipation and the Great Reform Act of 1832.

The Wellington Boot: This famous caricature likely relates to the political maneuvering around Catholic Emancipation (1829), possibly depicting Peel trying to fit into Wellington's political 'boots' or dealing with the consequences of the policy. It became an iconic image associated with the political struggles of the era.

Shooting Pigs in Dublin: This print exemplifies Heath's willingness to tackle sensitive issues, using satire to comment on British administration and policy in Ireland, a recurring source of political tension.

The Field of Battersea (1829): Heath depicted the notorious duel fought between the Duke of Wellington (then Prime Minister) and the Earl of Winchilsea over the issue of Catholic Emancipation, capturing the absurdity and high drama of the event.

Political Billiards: Another example of his political commentary, likely using the metaphor of a billiard game to represent the complex strategies and conflicts between political factions.

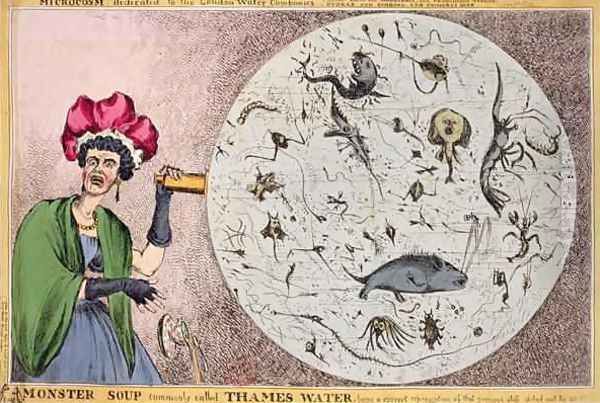

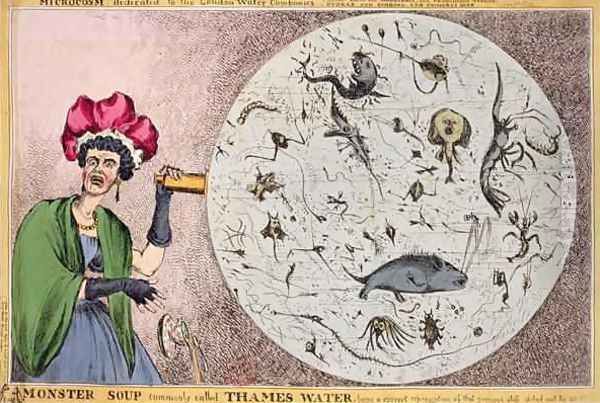

Microcosm, dedicated to the London Water Companies (also known as Monster Soup, 1828): Perhaps one of his most famous social satires, this print grotesquely visualizes the impurities allegedly found in London's drinking water supplied by private companies. An elderly woman drops her teacup in horror as she examines a drop of Thames water under a microscope, revealing monstrous creatures. It was a powerful piece of public health commentary wrapped in grotesque humour.

Beyond specific events, Heath consistently lampooned social pretensions, the excesses of fashion (particularly dandyism and elaborate women's hats and hairstyles), the inconveniences of urban life, and the general absurdities of human behaviour. He also displayed an interest in technology and machinery, sometimes creating images of fantastical, overly complex contraptions in a style that prefigures the "Rube Goldberg" machines of a later era.

Artistic Style and Techniques

William Heath primarily worked with etching, often combined with aquatint for tonal effects. His prints were typically issued hand-coloured, a laborious process usually carried out by teams of colourists working for the publishers. This hand-colouring lent the prints a vibrancy and immediacy that contributed significantly to their popular appeal. Heath was also proficient in watercolour, likely using it for preparatory sketches or finished drawings that served as models for the prints.

His drawing style is often characterized by its energy and dynamism. Figures are frequently exaggerated, posed in dramatic or comical attitudes. While some critics, both contemporary and modern, have found his draughtsmanship less refined or subtle than that of artists like George Cruikshank or later figures like John Doyle ("HB"), Heath's style possessed a vigour and directness well-suited to the immediate impact required of popular satire. His compositions could be crowded and complex, packed with incident and detail, demanding close examination from the viewer. He was incredibly prolific, sometimes issuing multiple prints in a single week, which occasionally led to accusations of haste or uneven quality, yet his overall output remained remarkably consistent in its satirical bite.

The Context of Contemporaries

William Heath operated within a rich ecosystem of graphic satirists, illustrators, and publishers. His work should be understood in relation to several key figures:

James Gillray (1756-1815) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827): These were the towering figures of the preceding generation, establishing the "Golden Age" of English caricature. Heath inherited their tradition of biting political and social commentary, though his style was generally less savage than Gillray's fiercest work and perhaps less focused on pure social observation than Rowlandson's.

George Cruikshank (1792-1878): Heath's most significant contemporary and rival. Cruikshank was immensely talented and prolific, eventually achieving greater fame and longevity. They sometimes collaborated, particularly in the earlier part of Heath's satirical career, working with the radical publisher William Hone (1780-1842) on pamphlets critical of the government in the years following Waterloo. However, they were also competitors in the bustling print market.

Isaac Cruikshank (c. 1764-1811?): George's father, also a notable caricaturist, representing the generation immediately preceding Heath.

Henry Heath (fl. 1822-1842?): Likely William's brother, Henry was also a caricaturist active during the same period. His style sometimes bears resemblance to William's, and their works can occasionally be confused, though Henry's output was generally less substantial.

Robert Seymour (1798-1836): A younger contemporary whose humorous illustrations, particularly his sporting scenes and work on Dickens's Pickwick Papers (before his suicide), gained popularity in the 1830s. Some critics felt Seymour possessed a finer sense of comic characterisation than Heath.

John Doyle (1797-1868): Signing his work "HB," Doyle emerged in the late 1820s and achieved great success in the 1830s and 1840s with his political sketches. Using lithography, Doyle offered a more subtle, portrait-focused, and less overtly grotesque style of political commentary that appealed to a more 'refined' audience and perhaps contributed to the perceived decline in popularity of the more boisterous etched caricatures of Heath and Cruikshank.

Other Caricaturists: The period saw many other active figures, such as Charles Jameson Grant (fl. 1830-1852), known for his often cruder but energetic woodcut illustrations for cheaper publications, and earlier figures like Robert Dighton (1751-1814) who specialized in portrait caricatures.

Publishers: Heath's work was disseminated by leading print publishers of the day, including Thomas McLean, S.W. Fores, and George Humphrey, whose shops were crucial hubs for the consumption of news and satire.

This network of artists and publishers created a dynamic environment where styles influenced each other, rivalries flourished, and the public was constantly supplied with visual commentary on the latest events.

Later Career and Legacy

Sources suggest that William Heath's dominance in the caricature market began to wane somewhat after 1830 or 1831. This may have been due to several factors. The rise of John Doyle's ("HB") more restrained lithographic style offered a popular alternative. The increasing use of wood engraving for illustrations in cheaper periodicals also began to change the landscape of popular imagery. Perhaps Heath's own prolific output led to a certain repetition, or maybe his energetic but sometimes less polished style fell slightly out of fashion as early Victorian tastes began to emerge.

Despite this relative decline in prominence compared to his peak in the 1820s, Heath continued to produce work throughout the 1830s. He died relatively young, passing away in Hampstead, London, in April 1840, at the age of about 45.

William Heath's legacy is that of a highly productive, influential, and often sharply witty satirist during a key transitional period in British art and society. He chronicled the shift from Regency excess to the cusp of the Victorian era with tireless energy. His pioneering work on The Northern Looking-Glass marks a significant step in the development of the comic magazine. While perhaps lacking the artistic finesse of Rowlandson or the sustained intensity of Gillray, and ultimately overshadowed by the long career of George Cruikshank, Heath produced a body of work that remains an invaluable resource for understanding the politics, social customs, and visual culture of his time. His "Paul Pry" persona captured the inquisitive spirit of the age, and his memorable images, like Monster Soup, continue to resonate as potent examples of graphic satire. He was a vital contributor to the visual conversation of his era.

Conclusion

William Heath was more than just a footnote in the history of caricature. He was a central figure in the London print market for two decades, adapting his art from military illustration to incisive social and political commentary. His adoption of the "Paul Pry" pseudonym, his groundbreaking work on The Northern Looking-Glass, and his vast output of hand-coloured etchings make him a subject worthy of study. Though operating in the shadow of giants like Gillray and Cruikshank, Heath's unique energy, topicality, and occasional brilliance ensured his voice was a prominent one in the satirical chorus of Regency and early Victorian Britain. His work remains a vivid, humorous, and often critical reflection of the society he observed so keenly.