Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel stands as one of the towering figures of 19th-century German art. Born during the Napoleonic Wars and living well into the era of burgeoning modernism, his life and career spanned a period of immense social, political, and industrial transformation in Germany. Menzel was a master of observation, renowned for his unwavering commitment to realism, his astonishing technical skill across various media, and his ability to capture both the grandeur of historical events and the intimate, often overlooked moments of everyday life. Primarily known as a painter and illustrator, his influence extended beyond his native Prussia, marking him as a significant European artist whose work often prefigured later movements like Impressionism.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Adolph Menzel was born on December 8, 1815, in Breslau, Silesia, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia (now Wrocław, Poland). His father, Carl Julius Menzel, ran a lithography printing shop, providing the young Adolph with his earliest exposure to the visual arts and printing techniques. The family moved to Berlin in 1830, seeking better opportunities. However, tragedy struck just two years later when Carl Julius died, leaving the sixteen-year-old Adolph responsible for supporting his mother and younger siblings by taking over the family lithography business.

Despite the heavy burden of responsibility, Menzel's artistic inclinations were undeniable. He briefly attended the Berlin Academy of Art (Königliche Akademie der Künste) in 1833, studying plaster casts and antique sculptures. However, his formal training was short-lived, lasting only about six months. Menzel was largely self-taught, honing his skills through relentless practice, keen observation of the world around him, and the practical demands of the lithography workshop. During this formative period, he formed a crucial friendship with the wallpaper manufacturer and patron Carl Heinrich Arnold, who recognized his talent and provided support.

Menzel's early professional work centered on illustration, a field where his precision and narrative skill quickly became apparent. He produced lithographs for various publications, including illustrations for Goethe's poem "Künstlers Erdenwallen" (Artist's Earthly Pilgrimage) in 1833. These early works already hinted at the meticulous attention to detail and the dynamic sense of life that would characterize his mature style. The necessity of running the family business instilled in him a strong work ethic and a deep understanding of graphic processes that would inform his art throughout his long career.

The Illustrator Emerges: The History of Frederick the Great

A pivotal moment in Menzel's early career came in 1839 when he was commissioned by the publisher Franz Kugler to illustrate his monumental Geschichte Friedrichs des Großen (History of Frederick the Great). This project, which occupied Menzel until 1842, involved creating around 400 intricate wood engravings. It was an undertaking that demanded not only artistic skill but also rigorous historical research. Menzel immersed himself in the era of Frederick II, studying uniforms, architecture, furniture, and historical accounts to ensure the accuracy of his depictions.

The resulting illustrations were a triumph. They brought the age of Frederick the Great to life with unprecedented vividness and detail, capturing everything from grand battles and court ceremonies to intimate moments in the king's life. The success of these illustrations catapulted Menzel to national fame. They were widely praised for their historical authenticity, their dynamic compositions, and their technical brilliance, significantly advancing the art of wood engraving in Germany. This project cemented Menzel's reputation as a master illustrator and established his lifelong fascination with the figure of Frederick the Great, who would become a recurring subject in his later paintings.

The Frederick the Great illustrations demonstrated Menzel's unique ability to blend historical accuracy with artistic vitality. He didn't just depict events; he recreated the atmosphere and psychology of the past. This deep engagement with history, combined with his innate observational powers, laid the groundwork for his transition into historical painting, where he would apply the same principles of meticulous research and realistic portrayal on a larger scale.

Mastering History: Frederick the Great on Canvas

Building on the success of his illustrations, Menzel turned his attention increasingly towards painting in the 1840s. His deep knowledge of Prussian history, particularly the era of Frederick the Great, provided fertile ground for ambitious historical canvases. He sought to portray the famous monarch not just as a symbol of Prussian power, but as a complex human being within his specific historical context. This required the same painstaking research he had applied to his illustrations, often involving visits to historical sites and the study of period artifacts.

One of his most famous works from this period is The Round Table at Sanssouci (1850), depicting Frederick the Great engaged in conversation with Voltaire and other Enlightenment figures at his summer palace. The painting is remarkable for its detailed rendering of the Rococo interior, the individual characterization of each figure, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow. It captures the intellectual ferment of the era while maintaining a sense of historical authenticity.

Another celebrated work is The Flute Concert of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci (1850-1852). Here, Menzel portrays the king, an accomplished flutist, performing in the music room of his palace, surrounded by members of his court and musicians, including C.P.E. Bach at the harpsichord. The painting is a tour de force of detail, from the shimmering fabrics and gilded decorations to the expressive faces of the audience. Menzel masterfully uses artificial light sources – candles – to create a warm, intimate atmosphere, highlighting the cultural refinement of Frederick's court.

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Menzel continued to explore themes from Frederick's life and reign, including military subjects like Frederick the Great Addresses his Generals before the Battle of Leuthen (1859-1861). These historical paintings were highly esteemed for their accuracy and their contribution to a growing sense of Prussian national identity, particularly in the lead-up to German unification. Menzel's approach differed significantly from the idealized, often allegorical history painting common at the time; he aimed for a tangible, believable reconstruction of the past, grounded in meticulous observation. His work in this genre solidified his position as Germany's preeminent historical painter.

A Keen Observer of Modern Life

While Menzel achieved fame through his historical subjects, he was equally fascinated by the world around him – the rapidly changing landscape of 19th-century Berlin and the lives of its inhabitants. He possessed an insatiable curiosity about modern life, from grand state occasions to the gritty realities of industrial labor and the quiet moments of domesticity. This resulted in a significant body of work that chronicled contemporary society with the same sharp eye for detail he applied to history.

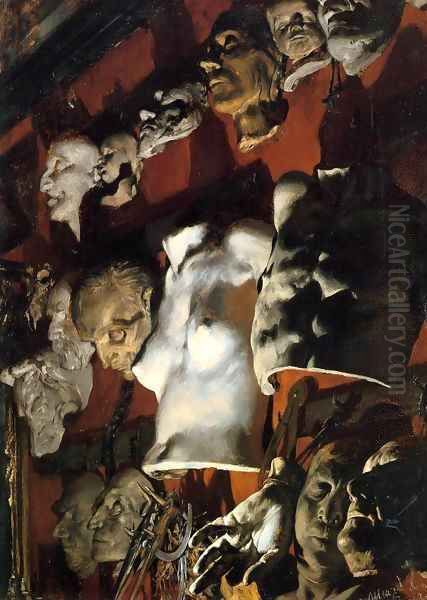

Perhaps his most famous depiction of modern industrial life is The Iron Rolling Mill (Modern Cyclops) (1872-1875). This powerful painting portrays the intense, physically demanding labor inside a railway track factory in Silesia. Menzel spent weeks sketching on-site, capturing the heat, noise, and relentless activity of the factory floor. The workers, stripped to the waist and straining against the machinery, are depicted with heroic realism, neither romanticized nor overtly politicized. The painting is a landmark work, one of the earliest and most compelling artistic representations of heavy industry in Europe, reflecting the profound societal shifts brought about by the Industrial Revolution.

Menzel also captured the pomp and circumstance of official life in the newly unified German Empire. His large canvas The Coronation of Wilhelm I as King of Prussia in Königsberg Castle (commissioned 1861, completed 1865) is a complex group portrait filled with hundreds of accurately rendered figures. Later, he depicted events like The Departure of King Wilhelm I for the Army on July 31, 1870, capturing the patriotic fervor of the Franco-Prussian War.

Beyond grand events and industrial scenes, Menzel painted numerous smaller works depicting everyday Berlin life: bustling street scenes, elegant interiors, theater audiences (Théâtre du Gymnase, 1856), and social gatherings. These works reveal his sharp sociological observation and his ability to capture fleeting moments with immediacy and psychological insight. He was drawn to the visual spectacle of modern urban existence, documenting its energy, its contrasts, and its human dramas.

Intimate Spaces and Proto-Impressionism

Alongside his public-facing historical and contemporary scenes, Menzel produced a remarkable series of smaller, more private paintings, often depicting interiors and intimate domestic moments. These works, frequently painted for his own satisfaction rather than for public exhibition, reveal a surprisingly modern sensibility and are often cited as precursors to French Impressionism. They showcase his innovative approach to light, color, and composition, often diverging significantly from academic conventions.

One of the most striking examples is The Balcony Room (1845). This small painting depicts an empty room with sunlight streaming through a tall window, reflecting off the polished floor. A curtain billows gently in the breeze entering through the open balcony door. The subject is simple, almost mundane, yet Menzel transforms it through his extraordinary sensitivity to light and atmosphere. The focus is not on narrative but on the transient effects of light and air within an enclosed space. The loose brushwork and the emphasis on capturing a specific moment in time anticipate Impressionist concerns by several decades.

Similarly, Menzel's Bedroom in the Ritterstrasse (1847) and The Artist's Sister with a Candle (1847) demonstrate this private, experimental side of his art. These works often feature unusual viewpoints, cropped compositions, and a focus on the interplay of natural and artificial light. The handling of paint can be remarkably free and suggestive, prioritizing visual sensation over meticulous finish. While Menzel never fully embraced the Impressionist aesthetic or its theoretical underpinnings, these intimate works reveal a shared interest in capturing the fleeting, subjective experience of vision. Artists like Edgar Degas, known for his own innovative compositions and depictions of modern life, would later express admiration for Menzel's work.

These private paintings highlight Menzel's versatility and his willingness to experiment beyond the expectations associated with his public commissions. They offer a glimpse into his personal artistic explorations and demonstrate his profound understanding of the purely pictorial qualities of painting – light, color, texture, and composition – anticipating developments that would revolutionize European art in the latter half of the 19th century.

The Draftsman and Printmaker

Underpinning all of Menzel's artistic achievements was his extraordinary skill as a draftsman. Drawing was fundamental to his practice, a daily discipline he maintained throughout his life. He produced thousands upon thousands of drawings, ranging from quick sketches capturing fleeting observations to highly detailed studies for his paintings and illustrations. His preferred media included pencil, charcoal, chalk, watercolor, and gouache, often used in combination.

His early training and work in lithography provided a solid foundation in graphic techniques. His mastery of wood engraving, demonstrated in the Frederick the Great illustrations, set a new standard for the medium in Germany. But it was perhaps in his pencil drawings that his genius for observation and rendering shone brightest. He drew everything: people, animals, architecture, landscapes, machinery, furniture, hands, fabric folds. No detail was too small or insignificant for his attention. His drawings served as a vast visual encyclopedia, a repository of information that he drew upon for his larger works.

Menzel's drawings are not merely preparatory studies; they are often powerful works of art in their own right. They reveal his analytical mind, his ability to grasp the essential structure and character of his subjects, and his sensitivity to texture and light. He often focused on seemingly mundane objects or fragments of scenes, investing them with a remarkable sense of presence and solidity. His drawings of workers' hands, tools, or pieces of machinery, for instance, possess a tactile quality and a dignity that elevates them beyond simple documentation.

His commitment to drawing remained unwavering even in old age. This constant practice of observing and recording the world around him was the bedrock of his realism. It allowed him to achieve the high degree of verisimilitude and detail that characterized his paintings and illustrations, grounding even his most complex historical reconstructions in tangible reality. His prolific output as a draftsman constitutes a major part of his artistic legacy.

Personal Life and Character

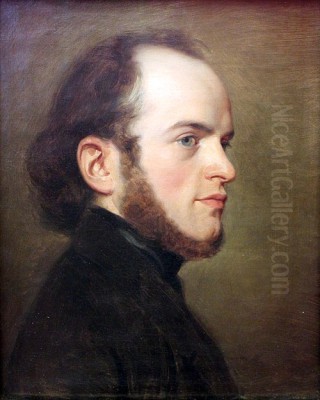

Adolph Menzel's personal life was marked by a singular dedication to his art, often at the expense of social engagement. Physically, he was unusually short, reportedly standing around four feet six inches tall, with a disproportionately large head. This physical characteristic may have contributed to a sense of detachment or awkwardness in social situations. He never married and lived for much of his adult life with his sister Emilie and later his brother Richard's family, maintaining a relatively secluded existence focused almost entirely on his work.

Contemporaries described him as industrious, disciplined, and intensely observant, but also somewhat solitary and occasionally gruff. He was known for his relentless work ethic, often drawing or painting for long hours each day. His studio was his sanctuary, filled with the sketches, props, and historical artifacts he used for his work. While respected and eventually highly honored, he seems to have kept a certain distance from the bustling social life of Berlin's artistic and intellectual circles, preferring the company of a few close friends, such as the writer Theodor Fontane and the historian Ferdinand Gregorovius.

His dedication was such that he famously wrote in his last will and testament: "Not only do I bequeath, but I protest: I have never had any, so called, pupils. I have, at most, had some 'helpers' among younger people at my side in my studio. And there has never been a 'school' founded by me either. Finally, I have to declare that I have never had any bond with the female sex." While the statement about pupils might be debatable given his later professorship, the sentiment reflects his intense focus and perhaps a perceived lack of conventional personal connections. This solitary nature, however, arguably fueled his art, allowing him the time and concentration required for his meticulous and labor-intensive approach.

Despite his reserved personality, Menzel was not entirely isolated. He traveled, attended concerts and theaters (subjects he sometimes depicted), and engaged with the intellectual currents of his time. His life, however, was overwhelmingly defined by his artistic production, a ceaseless drive to observe, record, and interpret the world through his art.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

Although deeply rooted in Berlin and Prussian culture, Menzel undertook several important journeys throughout his life that broadened his artistic horizons and provided new subjects for his work. Travel exposed him to different landscapes, cultures, and artistic traditions, enriching his visual vocabulary and occasionally influencing his style.

He made multiple trips to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world in the 19th century. These visits, particularly in the 1850s and 1860s, allowed him to see the work of contemporary French artists, including the Realists like Gustave Courbet and history painters like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, whose meticulous technique he admired. While in Paris, he sketched prolifically, capturing the city's life, architecture, and atmosphere, as seen in works like Théâtre du Gymnase.

Menzel also traveled to Vienna, where he experienced the vibrant cultural life of the Austro-Hungarian capital. Journeys to Italy exposed him to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, as well as the landscapes and daily life of the Italian peninsula. Visits to the Netherlands brought him into contact with the Dutch Golden Age masters, whose realistic depictions of everyday life likely resonated with his own artistic inclinations.

These travels provided Menzel with fresh perspectives and subject matter. He produced numerous sketches and paintings based on his experiences abroad, capturing everything from Alpine scenery to Venetian canals and Dutch interiors. While his core artistic identity remained firmly German and rooted in realism, his exposure to other European art scenes undoubtedly contributed to the richness and complexity of his work. It allowed him to situate his own art within a broader European context and likely reinforced his commitment to observing and depicting the realities of both past and present.

Artistic Network and Connections

Despite his somewhat solitary nature, Adolph von Menzel operated within a significant network of artists, writers, patrons, and institutions. His early connection with Carl Heinrich Arnold was crucial for his initial establishment in Berlin. His collaboration with the writer and art historian Franz Kugler on the Frederick the Great illustrations was a defining moment in his career.

As his fame grew, Menzel became a prominent figure in the Berlin art world. He was associated with the Berlin Academy of Art, first as a student, later as a member (from 1853), and eventually as a professor, teaching painting from 1875 until his death, although he maintained he never truly had "pupils" in the traditional sense. One notable artist who did receive instruction and guidance from him was the Swiss painter Karl Stauffer-Bern.

Menzel was aware of and engaged with the work of his contemporaries, both in Germany and abroad. He is often discussed alongside Caspar David Friedrich as one of the two dominant figures of 19th-century German painting, though their styles and concerns were vastly different – Friedrich embodying Romanticism's spiritual landscapes, Menzel championing empirical observation and realism. He knew other leading German Realists like Wilhelm Leibl. In the realm of historical painting, he was a contemporary of artists like Anton von Werner, who also depicted major events of Prussian history and German unification.

His relationship with French art was complex. He visited Paris and saw the works of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. While Menzel's realism developed independently, there are parallels in their shared interest in modern subjects and observational truth. His innovative compositions and handling of light, particularly in his private works, have led to comparisons with Edgar Degas. He also expressed admiration for the meticulous historical detail in the paintings of the French academic artist Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier. He also maintained connections with artists from other countries, such as the Danish painter Constantin Hansen. His circle of friends included prominent intellectuals like the novelist Theodor Fontane and the historian Ferdinand Gregorovius, indicating his engagement with the broader cultural life of Berlin.

Honors and Recognition

Adolph von Menzel's artistic achievements earned him widespread acclaim and numerous honors throughout his long career, solidifying his status as one of Germany's most celebrated artists. His reputation, initially built on his illustrations, grew exponentially with his historical paintings and depictions of contemporary life.

In 1853, he was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin. Official recognition continued to accumulate. He received the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts in 1874, one of the highest honors in Prussia. Perhaps the most significant accolade came in 1898 when he was elevated to the nobility by Kaiser Wilhelm II, becoming Adolph von Menzel. This honor coincided with his induction into the prestigious Order of the Black Eagle, the highest Prussian order of chivalry, making him the first painter ever to receive it.

Menzel was also granted the title of Excellency and became an honorary citizen of Berlin. His fame extended beyond Germany; he was made a member of various foreign academies, including the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and potentially associated with institutions like the Louvre in an honorary capacity. His works were exhibited internationally, including at the Paris Salons and World Fairs, where they garnered considerable attention.

His appointment as a professor at the Berlin Academy of Art further cemented his institutional standing. Despite his personal reserve and occasionally unconventional artistic choices (like his proto-Impressionist studies), Menzel achieved a level of official recognition rarely accorded to artists during their lifetime. This was partly due to the perceived national significance of his historical works, but also a testament to his undeniable technical mastery and the sheer force of his artistic vision. By the end of his life, he was regarded as a national treasure.

Later Years and Legacy

Adolph von Menzel remained artistically active well into his old age, his dedication to drawing and observation never waning. He continued to produce works that reflected his keen interest in the world around him, even as artistic styles began to shift dramatically towards Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and the beginnings of Expressionism. He died in Berlin on February 9, 1905, at the venerable age of 89. His death was treated as a major national event; Kaiser Wilhelm II himself walked behind his coffin during the state funeral procession, a remarkable tribute to the artist's stature.

Menzel bequeathed his vast artistic estate, including thousands of drawings and numerous paintings, to the National Gallery in Berlin, ensuring that his work would remain accessible to the public and cementing the museum's collection as the primary repository of his art. His legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a preeminent historical painter who brought the Prussian past, particularly the era of Frederick the Great, to life with unparalleled detail and psychological depth. He was also a pioneering chronicler of modern industrial and urban life, capturing the transformations of his time with unflinching realism.

His technical mastery, particularly in drawing and printmaking, remains highly admired. Furthermore, his more private, experimental works, with their innovative handling of light and composition, position him as an important precursor to Impressionism and modern art, demonstrating a forward-looking sensibility that coexisted with his more traditional historical output. Even artists far removed from his style, like Salvador Dalí, later expressed admiration, reportedly calling Menzel one of the greatest masters.

Together with Caspar David Friedrich, Menzel defines the pinnacle of German painting in the 19th century. While Friedrich explored the spiritual and sublime through landscape, Menzel grounded his art in the tangible realities of history and contemporary life, observed with an almost scientific precision yet infused with artistic vitality. His meticulous eye and unwavering dedication created a body of work that continues to fascinate and impress, offering invaluable insights into the art, history, and society of his time.

Conclusion

Adolph von Menzel was more than just a painter or an illustrator; he was a visual historian, a social commentator, and a relentless observer of the human condition. From the meticulously researched grandeur of Frederick the Great's court to the raw energy of the factory floor and the quiet intimacy of a sunlit room, his work encompasses the breadth of 19th-century German experience. His commitment to realism, combined with his exceptional technical skill and moments of surprising modernity, secured his place as a giant of German art. Though rooted in his time and place, the power of his observation and the intensity of his vision give his work an enduring relevance, making him a key figure not only in German art history but in the broader narrative of European realism and the emergence of modern art.