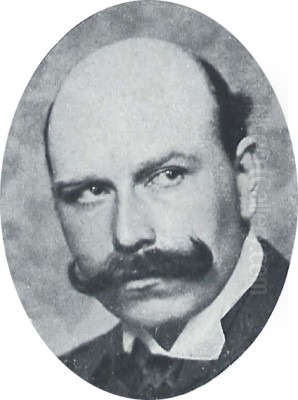

Arthur Kampf (1864-1950) stands as a significant yet complex figure in German art history. A prominent history painter, illustrator, and influential educator, his long career unfolded against the backdrop of tumultuous changes in Germany, from the late German Empire through the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich, into the post-war era. Associated primarily with the Düsseldorf School and later a central figure in Berlin's art establishment, Kampf's work reflects both the academic traditions of his time and the challenging political currents he navigated.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on September 28, 1864, in Aachen, then part of Prussia's Rhine Province, Arthur Kampf displayed artistic inclinations early on. His formal training took place at the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy), a powerhouse of German art education in the 19th century. He studied there from 1879 to 1891, immersing himself in the academic traditions that emphasized historical subjects, meticulous draftsmanship, and narrative clarity.

During his time at the Academy, Kampf was notably a student of Peter Janssen the Elder (1844-1908), a respected history painter himself. Janssen's influence, along with the broader ethos of the Düsseldorf School, shaped Kampf's early development, instilling in him a strong foundation in figure drawing, composition, and the grand manner of history painting. The school was known for its detailed, often narrative-driven style, which left a lasting mark on Kampf's approach.

Rise to Prominence and Academic Career

Kampf's talent was recognized relatively early. Even before completing his studies, he began making a name for himself. A pivotal moment came in 1886 with his painting The Last Statement (Die letzten Reden). This work, depicting the final moments of William I, German Emperor, garnered significant public attention and critical acclaim, effectively launching his career. Its success demonstrated his ability to handle large-scale historical compositions with technical proficiency and dramatic effect.

His growing reputation led to an academic appointment. In 1889, Kampf became an assistant professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, and shortly thereafter, a full professor. He remained associated with the institution where he had trained, contributing to its legacy by teaching a new generation of artists. However, his ambitions eventually drew him to the imperial capital.

Move to Berlin and Continued Success

Kampf later relocated to Berlin, the vibrant center of German political and cultural life. This move marked a new phase in his career, placing him at the heart of the national art scene. In Berlin, he continued to produce historical paintings, portraits, and genre scenes, solidifying his status as a leading academic painter. He became a member of the prestigious Prussian Academy of Arts, further cementing his position within the establishment.

His influence extended significantly into art education in Berlin. Kampf served as the director of the Hochschule für Bildende Künste (University of the Arts) in Berlin from 1915 to 1924. This leadership role placed him at the helm of one of Germany's most important art institutions during a critical period encompassing World War I and the early Weimar Republic. His tenure involved guiding the institution through challenging times and shaping its curriculum and direction.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Arthur Kampf's artistic style is primarily characterized by Naturalism and Realism, rooted in the academic traditions of the 19th century. He possessed exceptional technical skill, particularly in draftsmanship. His drawings are noted for their rigorous structure, confident lines, and clarity, reflecting a deep understanding of anatomy and form. This strong foundation is evident in his paintings.

His painted works often feature a relatively smooth finish, careful modeling of forms, and a focus on narrative clarity. Kampf excelled at depicting the human figure, often portraying idealized male and female forms, sometimes with an emphasis on musculature and athletic physiques, particularly in historical or allegorical contexts. His compositions typically demonstrate a strong sense of structure and often aim for depth and a clear focal point, with human figures dominating the scene.

Thematically, Kampf engaged with a range of subjects. History painting remained a cornerstone of his oeuvre, drawing on German history, mythology, and significant national events. However, he also turned his attention to contemporary life, depicting scenes of work, industry, and everyday occurrences, including somber moments like funerals. These works showcase his ability to observe and render the realities of modern existence within his established naturalistic framework. His work often carried a narrative quality, telling a story or capturing a specific dramatic moment.

Representative Works

Several key works mark Arthur Kampf's long career and illustrate his stylistic concerns and thematic interests:

The Last Statement (Die letzten Reden) (1886): As mentioned, this early work was crucial for establishing his reputation. Its depiction of a significant historical moment resonated with the public and demonstrated his mastery of the large-scale history genre favored by academic institutions.

Industry (Industrie): Kampf created murals and paintings on the theme of industry, reflecting an engagement with modern subjects. Works like The Open Hearth Furnace (Temperofen), acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1946, fall into this category, showcasing his ability to portray the power and activity of industrial settings with realistic detail.

David and Goliath (David und Goliath): This oil painting is often cited as one of Kampf's well-known works. However, its creation and reception, particularly during the Nazi era, are complex. Like other works produced during that period, it became associated with the regime's ideology, depicting themes of struggle and heroism that could be interpreted through a nationalistic lens.

The Victor (Der Sieger) (1941): Painted during World War II, this work depicts a victorious general and his troops. Its theme and timing clearly place it within the context of Nazi Germany, reflecting the glorification of military themes prevalent at the time.

Jungfrau von Hemmingstedt: This painting, depicting a historical scene related to the Battle of Hemmingstedt, gained notoriety for being purchased by Adolf Hitler in 1939 for the substantial sum of 12,000 Reichsmarks. This transaction highlights Kampf's acceptance and patronage by the highest levels of the Nazi regime.

Teaching and Influence

As a professor in both Düsseldorf and Berlin, and later as director of the Berlin Hochschule, Kampf played a significant role in German art education for decades. He taught numerous students, imparting the technical skills and academic principles he valued. Among his known pupils were artists such as Erich Beckerath, Imre Roth, Robert Balcke, Alfred Birkle, Georg Ehmig, Conrad Fliess, Erwin Freytag, Paul Heymann, Gustav Hilbert, and Maximilian Kleiner.

Another notable student was Ewald Mataré (1887-1965), who later became a significant sculptor and graphic artist. Interestingly, Mataré also studied under the prominent German Impressionist Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), indicating the diverse influences available to students in Berlin at the time. While Kampf provided a strong academic grounding, sources suggest his students did not necessarily follow rigidly in his stylistic footsteps, instead developing their own artistic paths. Kampf also actively participated in the art world through organizing exhibitions during his directorship, including international shows, fostering cultural exchange.

Navigating the Third Reich

Arthur Kampf's career extended into the Nazi era (1933-1945), a period that significantly complicates his legacy. Unlike artists associated with modernism, such as Max Liebermann (1847-1935) or Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), whose work was deemed "degenerate" and who faced persecution, Kampf's traditional, realistic style was acceptable to the regime. He became a member of the Nazi Party (NSDAP).

During this time, Kampf produced works that aligned with or could be interpreted through the lens of Nazi ideology. His history paintings, depictions of industry, and themes of heroism resonated with the regime's emphasis on national strength, work, and historical destiny. He created propaganda pieces, including portraits and allegorical works like David and Goliath. His relationship with prominent figures like Albert Speer (1905-1981), Hitler's chief architect, further indicates his proximity to the centers of power.

His standing within the Nazi cultural establishment was confirmed in 1944 when he was included on the "Gottbegnadeten list" (God-gifted list), a roster of artists considered crucial to Nazi culture, exempting them from military service. He also participated in state-sponsored exhibitions, such as the "Lob der Arbeit" (In Praise of Work) exhibition in 1936. There are conflicting accounts regarding his formal membership in artists' associations during this specific period, but his actions and the commissions he received clearly show his acceptance by and cooperation with the regime.

Despite this alignment, there are nuances. An anecdote relayed by his son, Otto Kampf, suggested that Arthur Kampf once painted a critical portrait of Hitler, though this remains an isolated claim. Nevertheless, his overall trajectory during the Third Reich was one of accommodation and participation, producing art that served, directly or indirectly, the regime's cultural politics. This involvement has led to criticism, with some commentators finding his work from this period, and sometimes his style in general, overly idealized, exaggerated, or lacking deeper critical engagement, serving instead to affirm established power structures. His style stood in stark contrast to the avant-garde movements of the time, aligning more closely with the conservative artistic tastes promoted by figures like Adolf Ziegler (1892-1959), another painter favored by the Nazis.

Artistic Relationships and Context

Kampf's career intersected with many other artists. His teacher, Peter Janssen, connected him to the Düsseldorf tradition. His contemporary and competitor in history painting, Hugo Freiherr von Habermann (though Klein-Chevalier was mentioned in the source, Habermann is another prominent figure of the era), represents the competitive academic environment. His student Ewald Mataré's connection to Lovis Corinth highlights the broader artistic landscape in Berlin, where Impressionism and Expressionism coexisted with academicism.

Comparing Kampf to other major figures provides context. Adolph Menzel (1815-1905), the giant of 19th-century German Realism and history painting, set a precedent that Kampf both inherited and adapted. Max Liebermann, a leading Impressionist and president of the Prussian Academy until forced out by the Nazis, represents the modernist path rejected by the regime that embraced artists like Kampf. Käthe Kollwitz's socially critical and emotionally raw work offers a stark contrast to Kampf's often more idealized or officially sanctioned themes. Figures like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) in Munich represented different, more Symbolist-inflected trends in German art. During the Nazi era, Kampf's position can be compared to sculptors like Arno Breker (1900-1991) and Josef Thorak (1889-1952), who also received major state commissions.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Arthur Kampf lived through the end of World War II and the immediate post-war years. He passed away on February 8, 1950, in Castrop-Rauxel, West Germany. His legacy remains debated. On one hand, he is recognized as a highly skilled academic painter and draftsman, a significant figure in German art education, and an artist who chronicled aspects of German history and life over a long period. His technical mastery, particularly in drawing, is often acknowledged, with his works included in studies like the Meisterzeichnungen (Master Drawings) series.

On the other hand, his career is inextricably linked to the political regimes under which he flourished, particularly the Third Reich. His willingness to align himself with the Nazi regime and produce art that supported its ideology casts a long shadow over his reputation. This makes assessing his work complex, requiring consideration of both its artistic merits and its historical context.

His works are held in various public collections, indicating their perceived historical and artistic importance. Institutions housing his art include the Cleveland Museum of Art in the United States, and major German museums such as the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe. While specific current market values are not readily available, the historical sale prices (like that of Jungfrau von Hemmingstedt) and the presence of his works in museum collections attest to their significance within the narrative of German art.

Conclusion

Arthur Kampf was a product of late 19th-century German academicism who successfully navigated the changing artistic and political landscapes of the first half of the 20th century. A master technician and influential teacher, he created a substantial body of work encompassing history painting, portraiture, and scenes of modern life. His adherence to a realistic style ensured his continued success even as modernism transformed the art world, and ultimately made him acceptable to the Nazi regime. His involvement during the Third Reich, however, remains a critical aspect of his biography, making him a case study in the complex relationship between art, artists, and political power. He endures as a notable, if controversial, figure in the history of German art, representing both the strengths and the potential pitfalls of the academic tradition in a turbulent era.