Adolphe Aizik Feder stands as a poignant figure in early 20th-century art, a member of the vibrant École de Paris whose life and career were tragically intertwined with the tumultuous history of his time. Born in Odessa and drawn to the artistic heart of Paris, Feder developed a distinct voice, capturing landscapes, portraits, and scenes reflecting his cultural heritage and travels. His promising career, however, was brutally cut short by the Holocaust. Yet, even in the darkest of circumstances, Feder continued to create, leaving behind powerful works that serve as both artistic achievements and vital historical testimonies. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Adolphe Feder.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Adolphe Aizik Feder was born in Odessa, then part of the Russian Empire (now Ukraine), in 1887. His initial artistic education took place in his hometown, a bustling port city with a significant Jewish cultural presence. Seeking broader horizons and more advanced training, the young Feder moved first to Berlin, immersing himself in the German art scene before ultimately being drawn to the undisputed center of the art world at the time: Paris.

He arrived in Paris around 1906, eager to absorb the innovative spirit pulsating through the city. Feder pursued formal studies at prestigious institutions, enrolling at the renowned École des Beaux-Arts and also attending the Académie Julian. The Académie Julian, in particular, was famous for its less rigid structure compared to the official École, attracting a diverse international student body, including many artists who would become key figures in modern art. Some accounts also suggest he may have spent time associated with the studio of Henri Matisse, a titan of modern painting known for his revolutionary use of color and form. This period was crucial for Feder, exposing him to a multitude of artistic currents and allowing him to hone his technical skills.

Paris and the École de Paris

Settling in Paris, Feder quickly became integrated into the dynamic artistic community known as the École de Paris (School of Paris). This term doesn't refer to a single style but rather to the incredible concentration of foreign-born artists who flocked to the city, particularly to the neighborhoods of Montmartre and Montparnasse, between the early 1900s and World War II. Feder found his place among the artists of Montparnasse, a melting pot of creativity, intellectual exchange, and bohemian life.

During his time in Paris, Feder established connections with several prominent artists associated with the Montparnasse scene. Among his known contacts were Amedeo Modigliani, the Italian painter celebrated for his elongated portraits and nudes; Othon Friesz, a French painter initially associated with Fauvism; and the sculptors Ossip Zadkine and Jacques Lipchitz, both key figures in modern sculpture who, like Feder, had Eastern European Jewish roots. This circle represented the diverse internationalism of the École de Paris, which also included luminaries such as Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Moïse Kisling, Jules Pascin, Constantin Brâncuși, and many others who were shaping the course of modern art. The atmosphere was one of intense artistic dialogue, experimentation, and mutual influence, even among artists working in distinct styles.

Artistic Development and Themes

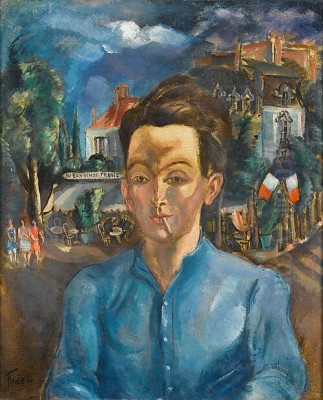

Feder's own artistic output was diverse. He worked proficiently across several genres, including landscape painting, still life, and portraiture. His early works, exhibited from 1912 onwards, likely reflected the influences of his academic training blended with the post-impressionist and modernist currents swirling around him in Paris. He became a regular participant in the major Parisian Salons, including the important Salon d'Automne, which was a key venue for avant-garde artists.

A significant aspect of Feder's oeuvre involved themes drawn from his Jewish heritage and broader interests in diverse cultures. He created large compositions with Jewish, Arab, and other "Oriental" subjects, reflecting both personal identity and a common fascination among European artists of the era with cultures perceived as exotic. This interest extended beyond painting; Feder developed a keen appreciation for what was then termed "primitive" art. He became a collector, acquiring African sculptures and Ethiopian paintings. This interest aligned him with many modernists, from Picasso to Modigliani, who found inspiration in the formal power and expressive directness of non-Western art forms.

Travels and Exploration: The Journey to Palestine

Feder's exploration of cultural themes was further deepened by his travels. In 1926, he undertook a significant journey to Palestine. This visit had a profound impact on his artistic production, prompting him to create a series of works imbued with a strong sense of place and, according to some descriptions, a distinct "national character." These works likely depicted the landscapes, people, and daily life he encountered, filtered through his European artistic training but energized by the experience of the historic Jewish homeland. This journey reflects a pattern seen among other Jewish artists of the École de Paris, like Reuven Rubin or Mane-Katz, who also traveled to Palestine and incorporated its light and motifs into their art, exploring themes of identity, heritage, and renewal.

Exhibitions and Pre-War Recognition

Throughout the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s, Feder built a solid reputation. His regular participation in the Paris Salons demonstrated his acceptance within the mainstream art establishment, while his connections in Montparnasse kept him linked to more avant-garde circles. His work gained recognition beyond France as well. Records indicate that his paintings were exhibited in major international cities, including London, Moscow, and Chicago. This international exposure underscores his standing as a respected artist of the École de Paris before the outbreak of World War II tragically altered his fate and that of millions of others.

The Shadow of War: Resistance and Internment

The outbreak of World War II and the subsequent Nazi occupation of France brought disaster to Paris's vibrant artistic community, particularly its large number of Jewish artists. Adolphe Feder, being Jewish, was immediately at risk. Driven by a desire to fight against the occupiers, he attempted to join the French Resistance movement in Paris. Unfortunately, his efforts were discovered, leading to his arrest by the collaborationist French police or the Gestapo.

Following his arrest, Feder was interned at the Drancy transit camp, located just outside Paris. Drancy served as the main deportation hub for Jews from France to the Nazi death camps in Eastern Europe, primarily Auschwitz-Birkenau. Conditions in Drancy were harsh, characterized by overcrowding, poor sanitation, lack of food, and constant fear. Despite this harrowing environment, Feder, like several other artists interned there, managed to continue creating art.

Art as Testimony: The Drancy Drawings

Feder's work from his time in Drancy, primarily executed between 1942 and 1943, stands as the most poignant and historically significant part of his legacy. Using materials he could find, likely charcoal and pastels, he created numerous portraits of his fellow inmates. These drawings are remarkable documents, capturing the diverse cross-section of humanity imprisoned within the camp walls: workers, intellectuals, devoutly religious Jews, women, and children.

His portraits from this period are noted for their sensitivity and expressive power. Rather than mere documentary records, they convey a deep sense of empathy and capture the vulnerability and resilience of his subjects. He employed concise yet telling lines and subtle shading to depict individuals facing unimaginable circumstances. Two specific works often cited are A Woman with a Headscarf (1943) and A Boy Seated at a Table, on which rests a Yellow Star (1942). The latter image, depicting a child marked by the compulsory Jewish badge, is particularly heartbreaking. These works reflect Feder's keen observation skills and his profound understanding of human fragility under duress. His ability to create art in such conditions speaks volumes about the enduring human need for expression and testimony.

Feder's Drancy drawings are part of a significant body of work known as Holocaust art – art created by victims during or shortly after the Shoah. These works provide invaluable insights into the experiences of those persecuted by the Nazis, often conveying emotional truths that historical documents alone cannot capture. Feder's contribution, focusing on the individual faces within the anonymous horror of the camp, is a powerful act of remembrance and resistance against dehumanization. His work from this period has been recognized in studies of art created during the Holocaust, such as the book Salon de Refusés: Art in French Internment Camps.

Final Deportation and Legacy

Adolphe Feder's time in Drancy, and his artistic production there, eventually came to an end. He was subjected to further transfers within the brutal camp system, reportedly passing through the Jaktorow and Janowska labor camps. The Janowska camp, near Lviv (then Lwów, Poland, now Ukraine), was notorious for its extreme brutality and mass killings. Finally, in 1943, Adolphe Aizik Feder was deported from Drancy, likely on one of the numerous convoys heading east. He was sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in occupied Poland, where he was murdered shortly after arrival.

Adolphe Feder's legacy is twofold. He was an accomplished artist of the École de Paris, contributing to the rich tapestry of modern art centered in Montparnasse during the interwar years. His pre-war work, encompassing landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and culturally themed compositions, earned him recognition both in France and internationally. He moved among significant figures like Modigliani, Friesz, Zadkine, and Lipchitz, and his work reflected the era's engagement with modernism and diverse cultural influences, including his interest in African art, shared by contemporaries like Picasso and Derain.

However, his legacy is indelibly marked by his tragic fate during the Holocaust and the powerful art he created in its shadow. The drawings from Drancy serve as a crucial historical record and a moving testament to the human spirit's persistence in the face of unimaginable adversity. They ensure that Feder is remembered not only as an artist whose potential was brutally extinguished but also as a witness who used his talent to document the humanity of those condemned by Nazi barbarity. His life story reflects the experiences of many artists of the École de Paris, such as Chaim Soutine, Moïse Kisling, or Otto Freundlich, whose lives and careers were profoundly impacted or destroyed by the war and the Holocaust. Feder's art, particularly his final works, continues to resonate, reminding us of the individual lives lost and the enduring power of art to bear witness.