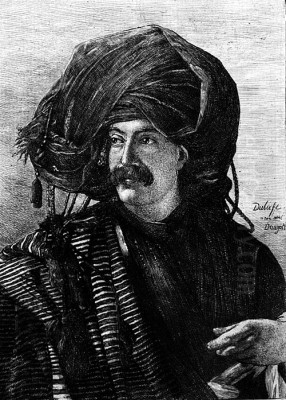

Adrien Dauzats (1804-1868) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. A painter, watercolourist, and lithographer, he carved a distinct niche for himself through his detailed landscapes, architectural studies, and, most significantly, his contributions to the burgeoning field of Orientalist art. His career was marked by extensive travels, prestigious collaborations, and a commitment to precision that set his work apart. Dauzats was not merely an artist of imagination; he was an intrepid documentarian, bringing back visual records from lands then considered exotic and remote to the European public.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bordeaux and Paris

Born in Bordeaux on July 16, 1804, Adrien Dauzats' early life was steeped in the world of theatre. His father was a set painter and carpenter at the Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux, an environment that undoubtedly exposed young Adrien to the mechanics of illusion, perspective, and grand visual narratives from a tender age. This theatrical grounding would subtly inform his later work, particularly his skill in composing complex architectural scenes and dramatic landscapes.

His formal artistic training began in his native Bordeaux, where he studied under the prominent local painter Pierre Lacour. Lacour, a respected figure in the Neoclassical tradition, would have instilled in Dauzats a foundation in drawing and composition. Dauzats also initially trained as a stage designer, a path that seemed natural given his upbringing. However, his ambitions soon extended beyond the confines of the theatre.

Seeking broader horizons, Dauzats moved to Paris to further his artistic education. There, he became a pupil of Michel Julien Gué, a landscape painter known for his historical and picturesque scenes. Under Gué's tutelage, Dauzats honed his skills in landscape painting, a genre that would remain central to his oeuvre. He also enrolled at the École de Dessin, further refining his draughtsmanship. By 1824, he had established himself as a landscape painter, ready to embark on a career that would take him far beyond the studios of Paris.

The Call of the Picturesque: Baron Taylor and the Voyages Pittoresques

A pivotal moment in Dauzats' early career was his association with Baron Isidore Justin Séverin Taylor. Taylor was an influential figure in the French art world – a writer, art collector, and commissioner of numerous artistic projects. He is best remembered for his monumental publishing venture, Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l'ancienne France (Picturesque and Romantic Journeys in Old France). This ambitious series, published over several decades starting in the 1820s, aimed to document the historical monuments and landscapes of France, region by region, using the relatively new medium of lithography.

Dauzats became one of the many talented artists enlisted by Baron Taylor to contribute illustrations to this grand project. His meticulous attention to detail, his skill in rendering architecture, and his ability to capture the unique atmosphere of a place made him an ideal contributor. He travelled extensively throughout France, sketching cathedrals, castles, ruins, and townscapes. These sketches were then transformed into lithographs, often by specialized printmakers, though Dauzats himself was proficient in the technique. His work for the Voyages Pittoresques helped to popularize a Romantic appreciation for France's medieval past and its diverse regional character. Other artists who contributed to this massive undertaking included Eugène Isabey, Richard Parkes Bonington, and Eugène Ciceri, creating a rich visual archive of pre-modern France.

The success of Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l'ancienne France led Baron Taylor to expand his scope. Dauzats accompanied him on further "picturesque journeys," most notably for Voyages pittoresques en Espagne, en Portugal, et sur la côte d'Afrique, de Tanger à Témour (Picturesque Journeys in Spain, Portugal, and on the Coast of Africa, from Tangier to Tétouan), published between 1826 and 1832. These travels provided Dauzats with new subjects and further solidified his reputation as a skilled topographical artist. His depictions of Spanish architecture, such as The Giralda, Seville, are celebrated for their accuracy and evocative power.

Journeys to the Orient: Documenting Distant Lands

The collaboration with Baron Taylor also opened the door for Dauzats to explore the "Orient," a term then used to describe a vast and somewhat vaguely defined region encompassing North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia. In 1830, Dauzats accompanied Taylor on a significant diplomatic and artistic mission to Egypt. The expedition's official purpose was to acquire the Luxor Obelisk for France, a gift from Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt.

This journey was transformative for Dauzats. He meticulously documented the landscapes, ancient monuments, and bustling city life of Egypt. He travelled along the Nile, sketched the temples of Karnak and Luxor, and captured the vibrant atmosphere of Cairo. His works from this period, such as Ahmed Ibn Tulun Mosque, mihrab and Mosquée du Tayloun, détail de la chaire (Mosque of Ibn Tulun, detail of the pulpit), demonstrate his keen eye for architectural detail and his ability to convey the grandeur of Islamic art and architecture. He was one of the first French artists to provide such detailed and seemingly objective visual records of these sites.

His travels in the Levant continued, taking him to Palestine, Syria, and Turkey. These experiences provided a wealth of material for his paintings and illustrations. He was not merely a tourist; he was an observer, keen to record the visual realities of the places he visited. This documentary impulse distinguished his work from some of the more overtly romanticized or fantastical depictions of the Orient produced by other artists. His approach was closer to that of the British artist David Roberts, who also travelled extensively in the Near East and produced highly detailed topographical views.

Artistic Style and the Nuances of Orientalism

Adrien Dauzats is primarily classified as an Orientalist painter, a genre that flourished in Europe throughout the 19th century. Orientalism, however, was not a monolithic style but rather a broad category encompassing diverse artistic responses to the cultures of the "Orient." Dauzats' brand of Orientalism was characterized by its precision, its focus on architectural and topographical accuracy, and a relatively restrained emotional palette compared to the more dramatic or sensual works of artists like Eugène Delacroix or Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Delacroix, a towering figure of French Romanticism, had travelled to Morocco and Algeria in 1832, and his sketches and paintings from this journey, filled with vibrant color and dynamic energy, had a profound impact on the development of Orientalist art. While Dauzats undoubtedly knew Delacroix and his work – they were contemporaries and moved in similar artistic circles – Dauzats' style remained more grounded in careful observation and detailed rendering. His early training in stage design and his work as an illustrator for Baron Taylor's Voyages likely reinforced this tendency towards clarity and precision.

His paintings and watercolors often feature strong light and shadow, emphasizing the textures of stone, the intricacies of ornamentation, and the vastness of desert landscapes. He was adept at capturing the quality of light in different environments, from the sun-drenched plains of Egypt to the shadowy interiors of mosques and palaces. Works like Fontaine à Alger (Fountain in Algiers) showcase this ability to render both architectural form and the play of light with remarkable skill.

While his work aimed for accuracy, it was not devoid of the picturesque or the romantic sensibility of his era. The choice of subject matter – ancient ruins, bustling souks, majestic mosques – inherently carried an element of the exotic for European audiences. However, Dauzats generally avoided the more stereotypical or sensationalist tropes that sometimes characterized Orientalist art, such as overtly eroticized harem scenes or violent encounters, which were more common in the works of artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (with his famous odalisques) or later, Gérôme. Instead, Dauzats focused on the tangible reality of the places he depicted, creating a visual record that, while filtered through a European lens, offered a valuable glimpse into these cultures.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Beyond the illustrations for Baron Taylor's publications, Adrien Dauzats produced a significant body of independent paintings and watercolors. Many of these were developed from sketches made during his travels and were exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

His Spanish subjects remained popular. The Giralda, Seville, as mentioned, is a prime example, capturing the iconic bell tower with a combination of architectural fidelity and atmospheric effect. His watercolors of Spanish scenes, such as a depiction of almond trees in bloom near Seville, demonstrate his sensitivity to landscape and his mastery of the watercolor medium, often employing techniques like dry brush to convey texture and light.

His Orientalist works are perhaps his most enduring contribution. Ahmed Ibn Tulun Mosque, mihrab is a testament to his ability to render complex Islamic architectural details and the serene grandeur of sacred spaces. Similarly, his views of Cairo, Jerusalem, and Damascus provided European audiences with vivid and detailed images of these historic cities.

The work Vue du val de l’Alger (View of the Valley of Algiers) reflects his time in North Africa, capturing the distinctive landscape and architecture of the region. Another piece, Arx de Triumphant de Djemilah (likely a slight misspelling of Arc de Triomphe de Djemila, referring to the Arch of Caracalla at the Roman ruins of Djémila in Algeria), indicates his interest in the classical past as well as contemporary Oriental scenes. His Paysage escarpé (Steep Landscape) could refer to various rugged terrains he encountered, from the mountains of Spain to the deserts of the Middle East.

A painting titled Bordeaux, Scène de marché (Bordeaux, Market Scene) shows that he did not entirely abandon French subjects, bringing his keen observational skills to depict everyday life in his native region.

Collaborations and Contemporaries: A Network of Artists and Writers

Dauzats' career was interwoven with collaborations and interactions with many prominent figures of his time. His long-standing association with Baron Taylor was foundational, providing him with opportunities for travel, publication, and patronage.

He was also a close friend of the celebrated writer Alexandre Dumas père. Dauzats accompanied Dumas on some of his travels, and their shared experiences led to literary collaborations. Dauzats provided illustrations for Dumas' travel narratives, and Dumas, in turn, wrote about their adventures. One notable collaboration was Quinze Jours au Sinaï (Fifteen Days in Sinai), an account of their journey to Mount Sinai, co-authored by Dumas and Dauzats, with Dauzats also providing the illustrations. He also contributed to Dumas' Impressions de Voyage: Le Véloce. This partnership between writer and artist was common in the 19th century, enriching both the textual and visual accounts of travel.

In the Parisian art world, Dauzats was acquainted with many leading artists. He was a member of the Société des Amis de l'Art (Society of Friends of Art), which brought him into contact with figures like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Théodore Rousseau. While Corot and Rousseau were primarily associated with the Barbizon School of landscape painting, their shared interest in capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere would have resonated with Dauzats.

His travels in Spain connected him with Spanish artists, including members of the Madrazo family, a prominent dynasty of painters. He also knew Pharamond Blanchard, another French painter who spent considerable time in Spain and the Orient. The Spanish artist Jenaro Pérez Villaamil also collaborated extensively with Baron Taylor on Spanish subjects, and their paths likely crossed.

The community of Orientalist painters was relatively close-knit, sharing an interest in similar subject matter and often undertaking similar journeys. Besides Delacroix and David Roberts, other notable Orientalists of the period or slightly later included Théodore Chassériau, Eugène Fromentin (who was also a writer), Horace Vernet (known for his battle scenes, including some in North Africa), and the British painter John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for many years. Dauzats' work, with its emphasis on accuracy, provided a valuable counterpoint to the more romantic or dramatic interpretations of these artists.

The Algerian Expeditions: Art in the Service of the State

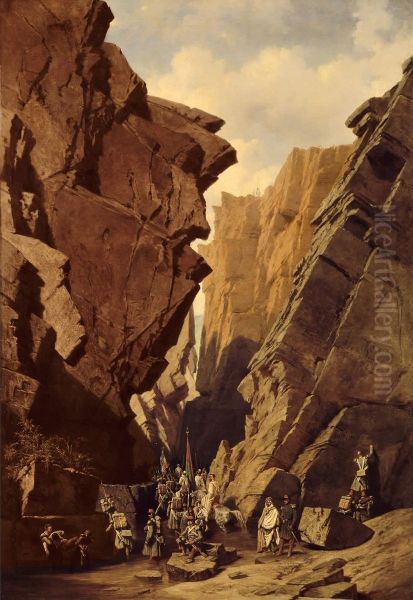

France's colonial involvement in Algeria, beginning with the invasion in 1830, created new opportunities and ethical complexities for artists. Dauzats participated in several French military expeditions in Algeria, including the notable "Expédition des Portes de Fer" (Expedition of the Iron Gates) in 1839, led by the Duc d'Orléans, son of King Louis-Philippe.

During these campaigns, Dauzats served as an official artist, tasked with documenting the military operations, the landscapes, and the local populations. His illustrations for Passage des Portes de Fer en Algérie (Passage of the Iron Gates in Algeria) provided a visual record of this challenging military campaign through a rugged mountain pass. These works, while fulfilling an official commission, also showcase his skill in depicting dramatic landscapes and group scenes.

His involvement in these expeditions places his work within the broader context of 19th-century military art and colonial representation. Artists like Denis Auguste Marie Raffet and Nicolas Toussaint Charlet were also known for their depictions of French military exploits. Dauzats' Algerian scenes, however, often retained his characteristic attention to topographical detail, offering more than just heroic portrayals of military prowess. They also documented the Algerian landscape and its people, albeit from the perspective of the colonizing power.

Salon Success and Official Recognition

Adrien Dauzats regularly exhibited his works at the Paris Salon, the most important venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. His submissions, often depicting scenes from his travels in Spain and the Orient, were generally well-received by critics and the public. His meticulous technique and the exotic appeal of his subjects ensured a degree of success.

He received several honors during his career, including the Legion of Honour, a prestigious French order of merit. His works were acquired by important collectors and entered public collections, including the Louvre and, later, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, as well as regional museums in France, such as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Pau. The Wallace Collection in London also holds works by Dauzats.

One notable instance of public acclaim was an exhibition in 1846 at the Bazar de la Nouvelle-Bourse, where his works reportedly attracted significant crowds and positive commentary, highlighting his standing in the Parisian art scene of the mid-19th century.

Later Years and Legacy

Adrien Dauzats continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, though perhaps with less prominence in his later years as artistic tastes began to shift with the rise of Realism and, subsequently, Impressionism. He passed away in Paris on February 18, 1868.

In the grand narrative of art history, Dauzats may not occupy the same celebrated position as Delacroix or Corot. However, his contributions are significant, particularly in the realms of topographical illustration and Orientalist painting. His work for Baron Taylor's Voyages Pittoresques played a crucial role in documenting and popularizing France's architectural heritage and the landscapes of Spain and North Africa. The sheer volume and quality of his lithographs for these series are a testament to his skill and industry.

As an Orientalist, Dauzats offered a vision of the East that, while still framed by European perspectives, emphasized careful observation and detailed representation. His paintings and watercolors provide valuable visual records of regions undergoing significant change, capturing monuments, cityscapes, and ways of life that have since been altered or have disappeared. His commitment to accuracy made his work a useful resource for historians and ethnographers, even as it appealed to the 19th-century European fascination with the exotic.

While the term "Orientalism" itself has come under critical scrutiny in post-colonial studies for its tendency to exoticize or stereotype non-Western cultures, Dauzats' work, with its relatively documentary approach, often fares better under such examination than that of some of his more overtly romanticizing contemporaries. His art invites viewers to look closely, to appreciate the intricacies of architecture, the quality of light, and the specificities of place.

Conclusion: A Precise Eye on a Changing World

Adrien Dauzats was an artist of remarkable diligence and skill. His legacy rests on his extensive body of work as an illustrator, a painter of landscapes and architecture, and a key figure in the first generation of French Orientalist artists. His meticulous depictions of France, Spain, Egypt, the Levant, and North Africa offer a fascinating window into the 19th-century world, seen through the eyes of a dedicated and observant traveler.

His collaborations with Baron Taylor and Alexandre Dumas placed him at the intersection of art, literature, and exploration. While the grand Romantic gestures of some of his contemporaries might have overshadowed his more measured approach, Dauzats' commitment to precision and his ability to capture the essence of a place ensure his enduring importance. His art serves not only as a source of aesthetic pleasure but also as a valuable historical document, chronicling a world on the cusp of modernity with a precise and unwavering eye. He remains a testament to the power of art to record, interpret, and transport, bridging geographical and cultural distances through the universal language of visual representation.