Agostino Aglio (1777-1857) stands as a fascinating figure in the art history of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. An Italian by birth who spent a significant portion of his prolific career in England, Aglio was a versatile artist whose skills encompassed painting, draughtsmanship, engraving, lithography, and decorative arts. His meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the reproduction of antiquities and the execution of grand decorative schemes, secured him a unique place, bridging the worlds of Neoclassicism, the burgeoning Romantic interest in the exotic, and the scholarly pursuit of ancient civilizations. This exploration delves into his life, his artistic training, his major achievements, his collaborations, and his lasting, though sometimes overlooked, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Italy

Born on December 15, 1777, in the historic city of Cremona in Lombardy, Italy, Agostino Aglio's artistic journey began in a region rich with artistic heritage. His family later moved to Milan, a vibrant cultural hub, which provided the young Aglio with greater opportunities for artistic education. He enrolled at the prestigious Brera Academy (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera), where he studied under two notable figures of Italian Neoclassicism: Andrea Appiani (1754-1817) and Giacomo Albertoli (1761-1847).

Andrea Appiani, a leading Neoclassical painter, was renowned for his frescoes and portraits, often serving the Napoleonic regime in Italy. His style, characterized by graceful lines, idealized forms, and a sophisticated use of color, would have instilled in Aglio a strong foundation in academic drawing and painting. Appiani himself was influenced by artists like Raphael and Correggio, and his work exemplified the prevailing taste for classical clarity and order. Studying under Appiani exposed Aglio to the highest standards of contemporary Italian painting.

Giacomo Albertoli, on the other hand, was a distinguished architect and ornamental designer. His tutelage would have been crucial in developing Aglio's skills in decorative arts and architectural rendering. Albertoli's expertise in classical ornamentation and design principles provided Aglio with a practical understanding of how art could be integrated into architectural spaces, a skill that would prove invaluable in his later career. The combined influence of Appiani's painterly classicism and Albertoli's decorative precision shaped Aglio's versatile artistic approach. This period in Milan, amidst the intellectual and artistic currents of the late Enlightenment and the rise of Neoclassicism, was formative for the young artist, equipping him with the technical prowess and aesthetic sensibilities that would define his work. Other prominent Italian artists of this era, such as the sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and painters like Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844) in Rome, were setting the tone for a revival of classical ideals, an environment that Aglio was undoubtedly aware of and influenced by.

Journey to England and Early Collaborations

The early 19th century was a period of significant political upheaval in Italy, and like many artists and intellectuals, Aglio sought opportunities abroad. In 1803, he made a pivotal decision to move to England, a country that was then a major center for artistic patronage and intellectual curiosity, particularly concerning antiquities. His arrival in England marked the beginning of a long and productive phase of his career.

One of his earliest significant engagements in England was with the architect William Wilkins (1778-1839). Wilkins, a prominent figure in the Greek Revival movement in British architecture, had undertaken an extensive tour of Greece, Asia Minor, and Italy. He commissioned Aglio to assist in preparing the illustrations for his scholarly work, The Antiquities of Magna Græcia, which was published in 1807. This project involved Aglio creating detailed drawings and engravings of ancient Greek and Roman ruins in Southern Italy. His meticulous draughtsmanship and ability to capture architectural detail accurately were perfectly suited for such a task. This collaboration not only provided Aglio with stable work but also immersed him in the study of classical antiquities, further honing his skills and aligning him with the prevailing Neoclassical tastes of the British elite. Wilkins himself would go on to design significant buildings like the National Gallery in London and Downing College, Cambridge, and Aglio's contribution to his early publication helped establish Wilkins's scholarly reputation.

Aglio's talents were not confined to antiquarian illustration. He also found work as a decorative painter, a field where his Italian training under Albertoli proved highly advantageous. He collaborated with the celebrated English landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837) on decorative projects for prominent London venues such as the Covent Garden Theatre and the King's Theatre. While Constable is primarily remembered for his revolutionary landscapes, his involvement in decorative schemes, often in collaboration with artists like Aglio who possessed specialized skills, was not uncommon for artists of the period seeking diverse income streams. These collaborations demonstrate Aglio's integration into the London art scene and his ability to work alongside leading British artists.

The Monumental "Antiquities of Mexico"

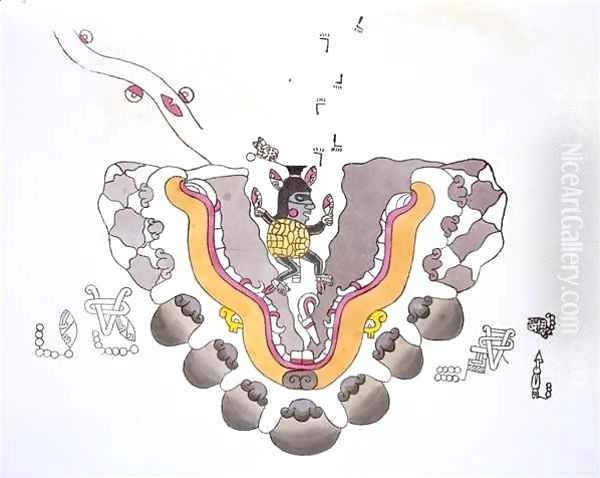

Perhaps Agostino Aglio's most significant and enduring achievement was his monumental work on Antiquities of Mexico. This ambitious project was conceived and funded by Edward King, Viscount Kingsborough (1795-1837), an eccentric Irish nobleman obsessed with proving that the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica were descended from the Lost Tribes of Israel. Despite the speculative nature of Kingsborough's theories, his passion led to one of the most ambitious publishing ventures of the 19th century.

Beginning around 1825, Kingsborough employed Aglio to travel to the great libraries and collections of Europe, including the Vatican Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the Royal Library in Dresden, and the Imperial Library in Vienna, to meticulously copy and trace pre-Columbian Mesoamerican codices. These codices, painted manuscripts created by the Maya, Aztec, Mixtec, and other indigenous peoples, are invaluable records of their history, mythology, rituals, and calendrical systems. Many of them had never been accurately reproduced or made accessible to a wider audience.

Aglio's task was immense. He spent years painstakingly hand-copying these fragile and complex documents, often working under difficult conditions. His dedication to accuracy was paramount. He reproduced the vibrant colors and intricate iconography of codices such as the Dresden Codex (a key Maya astronomical manuscript), the Codex Borgia (a ritual and divinatory manuscript from central Mexico), the Codex Vaticanus B (No. 3773), the Codex Laud, and parts of the Boturini Codex. The resulting facsimiles were then transformed into lithographs for publication.

The Antiquities of Mexico: comprising fac-similes of ancient Mexican paintings and hieroglyphics, preserved in the royal libraries of Paris, Berlin and Dresden; in the Imperial library of Vienna; in the Vatican library; in the Borgian museum at Rome; in the library of the Institute at Bologna; and in the Bodleian library at Oxford. Together with the Monuments of New Spain, by M. Dupaix was published in nine lavish folio volumes between 1830 and 1848. The first seven volumes appeared during Kingsborough's lifetime; the final two were published posthumously. Aglio was responsible for the vast majority of the lithographic plates, a testament to his skill and endurance.

While Kingsborough's theories were largely dismissed by later scholars, the publication itself was a landmark. It provided the first widespread, relatively faithful visual access to a significant corpus of Mesoamerican manuscripts. For scholars, researchers, and the interested public, Aglio's reproductions opened up a new world of ancient American art and writing. Despite the project's financial ruin for Kingsborough (who died in a debtors' prison), and some reported conflicts Aglio faced, possibly with the Roman Curia regarding access or with Kingsborough over artistic or financial matters, the artistic and scholarly value of Aglio's contribution is undeniable. His work laid a crucial foundation for the future study of Mesoamerican civilizations and remains a valuable resource even today, admired for its artistic fidelity.

Decorative Schemes and Architectural Embellishments

Beyond his work on manuscripts and antiquarian illustrations, Agostino Aglio was highly sought after for his talents in architectural decoration. His Italian training, with its emphasis on fresco and large-scale ornamental design, made him particularly adept at creating elaborate decorative schemes for both public and private buildings in England.

One of his most notable public commissions was for the Roman Catholic Chapel of St Mary Moorfields in London. Around 1818-1820, Aglio painted a large altarpiece depicting the Crucifixion for this significant new church, which was considered one of the largest Catholic churches in London at the time. His dramatic and emotive rendering of this central Christian scene would have been a prominent feature of the chapel's interior, showcasing his abilities in large-scale figurative painting in a style that blended Italianate traditions with the expectations of his British patrons.

Aglio also undertook decorative work for the Drury Lane Theatre, one of London's most important theatrical venues. Theatres of this era often featured opulent interiors, and artists like Aglio were employed to create painted decorations, ceiling murals, and other ornamental features that contributed to the grandeur of the theatrical experience. His involvement in such projects highlights his versatility and his ability to adapt his style to different contexts, from sacred spaces to places of public entertainment.

His skills were also in demand for private residences of the aristocracy. He executed decorative paintings at Woburn Abbey, the seat of the Dukes of Bedford, contributing to the lavish interiors of this stately home. Another significant project involved his work at Buckingham Palace, specifically in the "Pavilion Pompeii Room." Here, he collaborated with other notable artists, including Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793-1865), who later became President of the Royal Academy and Director of the National Gallery, and Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), famed for his animal paintings. This collaboration on a royal commission underscores Aglio's standing within the British art establishment. The Pompeian style, inspired by the recently excavated Roman city, was highly fashionable, and Aglio's classical training made him well-suited for such work. These decorative projects, while perhaps less internationally renowned than his Antiquities of Mexico, were a significant part of his oeuvre and contributed to the visual culture of Regency and early Victorian England.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Further Works

Agostino Aglio's artistic style was characterized by its adaptability and technical proficiency. Rooted in the Neoclassical tradition of his Italian training, his work consistently displays a high degree of precision, clarity of line, and careful attention to detail. This was evident in his architectural renderings for Wilkins, his meticulous copies of Mesoamerican codices, and his decorative designs.

He was a master of multiple techniques. As a painter, he could execute large-scale altarpieces and murals. As a draughtsman, his skill was foundational to all his endeavors. He was also an accomplished engraver and, significantly, one of the early adopters and skilled practitioners of lithography in Britain. Lithography, invented in the late 1790s by Alois Senefelder, was a relatively new printing technique that allowed for greater freedom and subtlety in reproducing drawings. Aglio's extensive use of lithography for the Antiquities of Mexico was a major undertaking and demonstrated his command of this medium, which was ideal for capturing the nuances of the original painted manuscripts.

Beyond the major projects already discussed, Aglio produced other notable works. One such example is his series Aztec Migration Myth, created between 1835 and 1840. These works, based on the Boturini Codex (which chronicles the legendary journey of the Aztecs from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico), were presented as both panoramic scrolls and individual paintings. They showcase his ability to interpret and visually narrate complex historical and mythological themes derived from non-European sources, further demonstrating his engagement with the "exotic" and the ancient.

His output also included landscapes and portraits, though these are less well-known than his antiquarian and decorative work. His son, Augustine Aglio Junior (c.1816-1885), also became an artist, working primarily in watercolor and later taking up photography, suggesting an artistic lineage and a shared familial interest in visual representation. Aglio Senior sometimes collaborated with his son on watercolor pieces. The fusion of Italian artistic traditions with the demands and opportunities of the British art market allowed Aglio to carve out a unique niche, producing a body of work that is remarkable for its diversity and consistent quality. His style, while not revolutionary in the manner of some of his Romantic contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) or William Blake (1757-1827), was perfectly suited to the scholarly and decorative tasks he undertook, emphasizing fidelity and skilled execution.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Agostino Aglio operated within a vibrant and diverse artistic milieu, both in Italy during his formative years and, more extensively, in England. His career spanned a period of significant artistic transition, from the dominance of Neoclassicism to the rise of Romanticism and the historical revivals of the Victorian era.

In Italy, his teachers Appiani and Albertoli were key figures in the Neoclassical movement, which looked to the art of ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration. This movement was championed by figures like the sculptor Antonio Canova and the painter Vincenzo Camuccini in Rome, and further north by artists like Francesco Hayez (1791-1882) in Milan, who would later become a leading figure of Italian Romanticism. Aglio's early training firmly placed him within this classical tradition.

Upon moving to England, Aglio entered a dynamic art world. Neoclassicism was still a powerful force, evident in the architecture of William Wilkins and the work of painters like Benjamin West (1738-1820), who, though American, was President of the Royal Academy for many years. However, Romanticism was gaining ascendancy, with artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable revolutionizing landscape painting. Visionary artists like William Blake and Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) explored more imaginative and subjective themes. Portraiture remained a lucrative field, dominated by figures like Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830).

Aglio's collaborations placed him in direct contact with some of these artists. His work with John Constable on decorative projects, and with Sir Charles Lock Eastlake and Sir Edwin Landseer at Buckingham Palace, indicates his acceptance and integration into the British artistic community. While his primary focus was often on antiquarian reproduction and decoration, his work shared the Romantic era's fascination with the past, albeit often a more distant or non-European past than that explored by some of his British contemporaries. The interest in historical subjects was also strong, with painters like Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786-1846) attempting grand historical canvases, and Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) achieving fame with his genre scenes that often had historical or narrative elements.

Aglio's specialized skills, particularly in accurately rendering ancient artifacts and creating decorative schemes in various historical styles (like the Pompeian), catered to a specific but important niche. The 19th century saw a surge in archaeological discovery and a widespread public interest in antiquities from around the world – Egypt, Greece, Rome, and, thanks in part to figures like Kingsborough and Alexander von Humboldt, the Americas. Aglio's work directly served this burgeoning interest, making him a key, if sometimes behind-the-scenes, contributor to the visual dissemination of historical knowledge.

Personal Life, Legacy, and Conclusion

Details about Agostino Aglio's personal life beyond his professional engagements are somewhat scarce, a common fate for artists who were not of the absolute first rank of celebrity in their time. We know he was born in Cremona, moved to Milan, and then to England in 1803, where he resided for the remainder of his life. He married Letitia Clarke and they had several children, including Augustine Aglio Junior, who followed in his father's artistic footsteps. This continuation of artistic practice within the family suggests a supportive domestic environment for his creative endeavors. Agostino Aglio passed away on March 1, 1857, in London, at the age of 79, after a long and industrious career.

Aglio's legacy is multifaceted. His most prominent contribution undoubtedly lies in the Antiquities of Mexico. Despite the flawed theoretical underpinnings of Kingsborough's project, Aglio's meticulous and beautiful reproductions of Mesoamerican codices were a landmark achievement. They provided scholars and the public with unprecedented access to these vital cultural documents, significantly impacting the early development of Mesoamerican studies. For many, these were the first images they would have ever seen of these ancient civilizations' artistic and intellectual achievements. His plates are still consulted and admired for their accuracy and artistry.

His work as a decorative painter and illustrator of classical antiquities, such as for Wilkins' Magna Græcia, also contributed to the visual culture of his time, reflecting and reinforcing the Neoclassical and historical revival tastes prevalent in Britain. His ability to work across various media – painting, fresco, watercolor, engraving, and lithography – marks him as an exceptionally versatile artist.

While Agostino Aglio may not be as widely known today as some of his more famous contemporaries like Constable or Turner, his contributions were significant. He was a skilled craftsman, a diligent scholar-artist, and a vital link in the chain of cultural transmission, bringing images of distant pasts and foreign lands to a European audience. His dedication to precision in reproduction, combined with his artistic sensibility, ensured that his work was not merely documentary but also possessed aesthetic merit. As an art historian, I see Agostino Aglio as a testament to the diverse roles artists play, not always as radical innovators, but often as crucial interpreters, preservers, and disseminators of visual culture, bridging worlds and eras through their meticulous and dedicated labor. His life and work offer a valuable insight into the transnational artistic networks and the burgeoning global consciousness of the 19th century.